Hair fetishism

Hair fetishism, also known as hair partialism and trichophilia, is a partialism in which a person sees hair – most commonly, head hair – as particularly erotic and sexually arousing.[1] Arousal may occur from seeing or touching hair, whether head hair, pubic hair, axillary hair, chest hair or fur. Head-hair arousal may come from seeing or touching very long or short hair, wet hair, certain colors of hair or a particular hairstyle. Pubic hair fetishism is a particular form of hair fetishism.

Haircut fetishism is a related paraphilia in which a person is aroused by having their head hair cut or shaved, by cutting the hair of another, by watching someone get a haircut, or by seeing someone with a shaved head or very short hair.

Etymology

Technically, hair fetishism is called trichophilia, which comes from the Greek "trica-" (τρίχα), which means hair, and the suffix "-philia" (φιλία), which means love.

Characteristics

Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals. In humans, hair can be scalp hair, facial hair, chest hair, pubic hair, axillary hair, besides other places. Men tend to have hair in more places than women. Hair does not in itself have any intrinsic sexual value other than the attributes given to it by individuals in a cultural context. Some cultures are ambivalent in relation to body hair, with some being regarded as attractive while others being regarded as unaesthetic. Many cultures regard a woman's hair to be erotic. For example, many Islamic women cover their hair in public, and display it only to their family and close friends.[2] Similarly, many Jewish women cover their hair after marriage. During the Middle Ages, European women were expected to cover their hair after they married.

Even in cultures where women do not customarily cover their hair, the erotic significance of hair is recognised. Some hair styles are culturally associated with a particular gender, with short head hair styles and baldness being associated with men and longer hair styles with women and girls, even though there are exceptions such as Gaelic Irish men, and also depictions of men in art throughout history, most notable example probably being that of Jesus Christ. Hair, especially head hair, is regarded as a person's secondary sexual characteristic. In the case of women especially, head hair has been presented in art and literature as a feature of beauty, vanity and eroticism. Hair has a very important role in the canons of beauty in different regions of the world, and healthy combed hair has two important function, beauty and fashion. In those cultures considerable time and expense is put into the attractive presentation of hair, and in some cases to the removal of culturally unwanted hair.

Hair fetishism manifests itself in a variety of behaviors. A fetishist may enjoy seeing or touching hair, pulling on or cutting the hair of another person.[3] Besides enjoyment they may become sexually aroused from such activities. It may also be described as an obsession, as in the case of hair washing or dread of losing hair. Arousal by head hair may arise from seeing or touching very long or short hair, wet hair, a certain color of hair or a particular hairstyle. Others may find the attraction of literally "having sex with somebody's hair" as a fantasy or fetish.[4] The fetish affects both men and women.

Some people feel pleasure when their hair is being cut or groomed. This is because they produce endorphins giving them a feeling which is similar to that of a head massage, laughter, or caress.[5] On the other hand, many people feel some level of anxiety when their head hair is being cut. Sigmund Freud stated that cutting woman's long hair by men may represent a fear and/or concept of castration, meaning that a woman's long hair represents a figurative penis and that by cutting off her hair a man may feel dominance[4] as castrator, not the castrated one (while paradoxically also being reassured by the fact that the hair will grow again).[6]

Tricophilia may present with different excitation sources, the most common, but not the only one, being human head hair. Tricophilia may also involve facial hair, chest hair, pubic hair, armpit hair and animal fur. The excitation can arise from the texture, color, hairstyle and hair length. Among the most common variants of this paraphilia are excitation by long hair and short hair, the excitement of blonde hair (blonde fetichism) and red hair (redhead fetichism) and the excitement of the different textures of hair (straight, curly, wavy, etc.). Tricophilia can relate to the excitement that is caused by plucking or pulling hair or body hair.

Hair fetishism comes from a natural fascination with the species on the admiration of the coat, as its texture provides pleasurable sensations. An infant develops this kind of pleasure to feel the hair on his or her early life, manifesting as aggressive behavior that will drive to pull the hair of people with which it interacts. Tricophilia is considered a paraphilia which is usually inoffensive.[7]

Prevalence

In order to determine the relative prevalence of different fetishes, scientists obtained a sample of at least 5000 individuals worldwide, in 2007, from 381 Internet discussion groups. The relative prevalences were estimated based on (a) the number of groups devoted to a particular fetish, (b) the number of individuals participating in the groups and (c) the number of messages exchanged. Of the sampled population, 7 percent were turned on by hair (as opposed to 12 for underwear, but only 4 for genitals, 3 for breasts, 2 for buttocks, and less than one for body hair).[8][9]

History

References to hair fetish can be found in ancient empires. In Norse mythology reference to the fetish is in the story of Sif, Thor's wife and goddess of fertility, who is admired for having beautiful pure gold hair.[10]

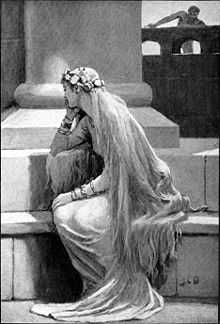

Hair has been a symbol of beauty, vanity and eroticism. In the story of Rapunzel by the Brothers Grimm published in 1812, there is an analogy to the beauty of Sif's hair with the story of a young woman with blond hair who is locked in a tower room, the only way to reach her being to climb the tower using her long hair.

In religious societies like Christianity, tonsure was customary and involved the cutting or shaving the hair from the scalp (while leaving some parts uncut), as a mark of purity of body.

Notable Hair Fetishists

John Key, Prime minister of New Zealand[11][12]

Danilo Restivo, Murderer in England[13]

See also

- Fur fetishism

- Hair theft

- Hairstyle

- Paraphilia

- Pubic hair fetishism

References

- ↑ Stanley E. Althof (14 January 2010). Handbook of Clinical Sexuality for Mental Health Professionals. Taylor & Francis. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-415-80075-4.

- ↑ Sherrow, Victoria (2006). Encyclopedia of hair: a cultural history. Greenwood. p. 2. ISBN 0-313-33145-6.

- ↑ Anne Hooper; DK Publishing (11 November 2002). Sexopedia. Penguin. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-7566-63520.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Parfitt, Anthony (2007). "Fetishism, Transgenderism, and the Concept of 'Castration'.". Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy 21 (1): 61–89. Retrieved 24 December 2011.(subscription required)

- ↑ Tyler Volk; Dorion Sagan (October 2009). Death/Sex. Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-60358-143-1.

- ↑ Otto Fenichel, The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis (1946) p. 349

- ↑ Studies in the Psychology of Sex, Volume 5, Havellock Ellis, 2004 book link

- ↑ Scorolli, C; Ghirlanda, S; Enquist, M; Zattoni, S; Jannini, E A (2007). "Relative prevalence of different fetishes". International Journal of Impotence Research 19 (4): 432–7. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3901547. PMID 17304204.

- ↑ Dobson, Roger. "Heels are the world's No 1 fetish". The Independent (London). Retrieved 1 February 2007.

- ↑ Sif Legend of the goddess Sif, THORSHOF (www.thorshof.org)

- ↑ "New Zealand prime minister John Key apologises for pulling waitress's hair". The Guardian. 22 April 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ "The Prime Minister has been labelled a hair fetishist". 3News. 23 April 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ↑ "'Killer had fetish for cutting women’s hair’, court hears". The Daily Telegraph. 17 May 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

External links

- Trichophilia - RightDiagnosis.com

- - ExtremeHaircut.com

| ||||||||||||||||||||