Hahn series

In mathematics, Hahn series (sometimes also known as Hahn-Mal'cev-Neumann series) are a type of formal infinite series. They are a generalization of Puiseux series (themselves a generalization of formal power series) and were first introduced by Hans Hahn in 1907[1] (and then further generalized by Anatoly Maltsev and Bernhard Neumann to a non-commutative setting). They allow for arbitrary exponents of the indeterminate so long as the set supporting them forms a well-ordered subset of the value group (typically  or

or  ). Hahn series were first introduced, as groups, in the course of the proof of the Hahn embedding theorem and then studied by him as fields in his approach to Hilbert's seventeenth problem.

). Hahn series were first introduced, as groups, in the course of the proof of the Hahn embedding theorem and then studied by him as fields in his approach to Hilbert's seventeenth problem.

Formulation

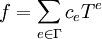

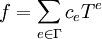

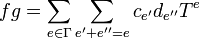

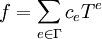

The field of Hahn series ![K[[T^\Gamma]]](../I/m/e1bae260e05a99990a28e839553d1a5d.png) (in the indeterminate T) over a field K and with value group Γ (an ordered group) is the set of formal expressions of the form

(in the indeterminate T) over a field K and with value group Γ (an ordered group) is the set of formal expressions of the form  with

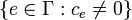

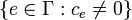

with  such that the support

such that the support  of f is well-ordered. The sum and product of

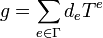

of f is well-ordered. The sum and product of  and

and  are given by

are given by  and

and  (in the latter, the sum

(in the latter, the sum  over values

over values  such that

such that  and

and  is finite because a well-ordered set cannot contain an infinite decreasing sequence).

is finite because a well-ordered set cannot contain an infinite decreasing sequence).

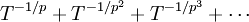

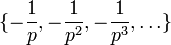

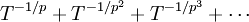

For example,  is a Hahn series (over any field) because the set of rationals

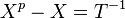

is a Hahn series (over any field) because the set of rationals  is well-ordered; it is not a Puiseux series because the denominators in the exponents are unbounded. (And if the base field K has characteristic p, then this Hahn series satisfies the equation

is well-ordered; it is not a Puiseux series because the denominators in the exponents are unbounded. (And if the base field K has characteristic p, then this Hahn series satisfies the equation  so it is algebraic over

so it is algebraic over  .)

.)

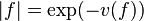

The valuation  of

of  is defined as the smallest e such that

is defined as the smallest e such that  (in other words, the smallest element of the support of f): this makes

(in other words, the smallest element of the support of f): this makes ![K[[T^\Gamma]]](../I/m/e1bae260e05a99990a28e839553d1a5d.png) into a spherically complete valued field with value group Γ (justifying a posteriori the terminology); in particular, v defines a topology on

into a spherically complete valued field with value group Γ (justifying a posteriori the terminology); in particular, v defines a topology on ![K[[T^\Gamma]]](../I/m/e1bae260e05a99990a28e839553d1a5d.png) . If

. If  , then v corresponds to an ultrametric) absolute value

, then v corresponds to an ultrametric) absolute value  , with respect to which

, with respect to which ![K[[T^\Gamma]]](../I/m/e1bae260e05a99990a28e839553d1a5d.png) is a complete metric space. However, unlike in the case of formal Laurent series or Puiseux series, the formal sums used in defining the elements of the field do not converge: in the case of

is a complete metric space. However, unlike in the case of formal Laurent series or Puiseux series, the formal sums used in defining the elements of the field do not converge: in the case of  for example, the absolute values of the terms tend to 1 (because their valuations tend to 0), so the series is not convergent (such series are sometimes known as "pseudo-convergent"[2]).

for example, the absolute values of the terms tend to 1 (because their valuations tend to 0), so the series is not convergent (such series are sometimes known as "pseudo-convergent"[2]).

If K is algebraically closed (but not necessarily of characteristic zero) and Γ is divisible, then ![K[[T^\Gamma]]](../I/m/e1bae260e05a99990a28e839553d1a5d.png) is algebraically closed.[3] Thus, the algebraic closure of

is algebraically closed.[3] Thus, the algebraic closure of  is contained in

is contained in ![K[[T^{\mathbb{Q}}]]](../I/m/0237eec6939e75aa712c09d5991bd88c.png) (when K is of characteristic zero, it is exactly the field of Puiseux series): in fact, it is possible to give a somewhat analogous description of the algebraic closure of

(when K is of characteristic zero, it is exactly the field of Puiseux series): in fact, it is possible to give a somewhat analogous description of the algebraic closure of  in positive characteristic as a subset of

in positive characteristic as a subset of ![K[[T^\Gamma]]](../I/m/e1bae260e05a99990a28e839553d1a5d.png) .[4]

.[4]

If K is an ordered field then ![K[[T^\Gamma]]](../I/m/e1bae260e05a99990a28e839553d1a5d.png) is totally ordered by making the indeterminate T infinitesimal (greater than 0 but less than any positive element of K) or, equivalently, by using the lexicographic order on the coefficients of the series. If K is real-closed and Γ is divisible then

is totally ordered by making the indeterminate T infinitesimal (greater than 0 but less than any positive element of K) or, equivalently, by using the lexicographic order on the coefficients of the series. If K is real-closed and Γ is divisible then ![K[[T^\Gamma]]](../I/m/e1bae260e05a99990a28e839553d1a5d.png) is itself real closed.[5] This fact can be used to analyse (or even construct) the field of surreal numbers (which is isomorphic, as an ordered field, to the field of Hahn series with real coefficients and value group the surreal numbers themselves[6]).

is itself real closed.[5] This fact can be used to analyse (or even construct) the field of surreal numbers (which is isomorphic, as an ordered field, to the field of Hahn series with real coefficients and value group the surreal numbers themselves[6]).

If κ is an infinite regular cardinal, one can consider the subset of ![K[[T^\Gamma]]](../I/m/e1bae260e05a99990a28e839553d1a5d.png) consisting of series whose support set

consisting of series whose support set  has cardinality (strictly) less than κ: it turns out that this is also a field, with much the same algebraic closedness properties as the full

has cardinality (strictly) less than κ: it turns out that this is also a field, with much the same algebraic closedness properties as the full ![K[[T^\Gamma]]](../I/m/e1bae260e05a99990a28e839553d1a5d.png) : e.g., it is algebraically closed or real closed when K is so and Γ is divisible.[7]

: e.g., it is algebraically closed or real closed when K is so and Γ is divisible.[7]

Hahn-Witt series

The construction of Hahn series can be combined with Witt vectors (at least over a perfect field) to form “twisted Hahn series” or “Hahn-Witt series”:[8] for example, over a finite field K of characteristic p (or their algebraic closure), the field of Hahn-Witt series with value group Γ (containing the integers) would be the set of formal sums  where now

where now  are Teichmüller representatives (of the elements of K) which are multiplied and added in the same way as in the case of ordinary Witt vectors (which is obtained when Γ is the group of integers). When Γ is the group of rationals or reals and K is the algebraic closure of the finite field with p elements, this construction gives a (ultra)metrically complete algebraically closed field containing the p-adics, hence a more or less explicit description of the field

are Teichmüller representatives (of the elements of K) which are multiplied and added in the same way as in the case of ordinary Witt vectors (which is obtained when Γ is the group of integers). When Γ is the group of rationals or reals and K is the algebraic closure of the finite field with p elements, this construction gives a (ultra)metrically complete algebraically closed field containing the p-adics, hence a more or less explicit description of the field  or its spherical completion.[9]

or its spherical completion.[9]

Surreal numbers

The field of surreal numbers can be regarded as the field of Hahn series with real coefficients and value group the surreal numbers themselves.[10]

See also

References

- Hahn, Hans (1907), "Über die nichtarchimedischen Größensysteme", Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien, Mathematisch - Naturwissenschaftliche Klasse (Wien. Ber.) 116: 601–655, JFM 38.0501.01 (reprinted in: Hahn, Hans (1995), Gesammelte Abhandlungen I, Springer-Verlag)

- MacLane, Saunders (1939), "The Universality of Formal Power Series Fields", Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 45: 888–890, doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1939-07110-3, Zbl 0022.30401

- Kaplansky, Irving (1942), "Maximal fields with valuations I", Duke Math. J. 9: 303–321, doi:10.1215/s0012-7094-42-00922-0, Zbl v

- Alling, Norman L. (1987). Foundations of Analysis over Surreal Number Fields. Mathematics Studies 141. North-Holland. ISBN 0-444-70226-1. Zbl 0621.12001.

- Poonen, Bjorn (1993), "Maximally complete fields", Enseign. Math. 39: 87–106, Zbl 0807.12006

- Kedlaya, Kiran Sridhara (2001), "The algebraic closure of the power series field in positive characteristic", Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 129: 3461–3470, doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-01-06001-4

- Kedlaya, Kiran Sridhara (2001), "Power Series and 𝑝-adic Algebraic Closures", J. Number Theory 89: 324–339, doi:10.1006/jnth.2000.2630

Notes

- ↑ Hahn (1907)

- ↑ Kaplansky (1942, Duke Math. J., definition on p.303)

- ↑ MacLane (1939, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc., theorem 1 (p.889))

- ↑ Kedlaya (2001, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc.)

- ↑ Alling (1987, §6.23, (2) (p.218))

- ↑ Alling (1987, theorem of §6.55 (p. 246))

- ↑ Alling (1987, §6.23, (3) and (4) (p.218–219))

- ↑ Kedlaya (2001, J. Number Theory)

- ↑ Poonen (1993)

- ↑ Alling (1987)