HMS Emerald (1795)

Emerald's sister ship Amazon (right) engaging the French frigate, Droits de l'Homme (centre), with HMS Indefatigable (left) | |

| Career | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Emerald |

| Ordered: | 24 May 1794 |

| Builder: | Thomas Pitcher |

| Cost: | £14,419 |

| Laid down: | June 1794 |

| Launched: | 31 July 1795 |

| Commissioned: | August 1795 |

| Fate: | Broken up, January 1836 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Amazon |

| Type: | Fifth-rate frigate |

| Tons burthen: | 933 67⁄94 (bm) |

| Length: | 143 ft 2.5 in (43.650 m) (gundeck) 119 ft 5.5 in (36.411 m) (keel) |

| Beam: | 38 ft 4 in (11.68 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m) |

| Propulsion: | Sails |

| Complement: | 264 |

| Armament: | 36 guns |

HMS Emerald was one of the 36-gun, Amazon class frigates, designed by Sir William Rule for the Royal Navy in 1794. She was ordered towards the end of May 1794 and work began the following month at Thomas Pitcher's dockyard in Northfleet and was completed on 12 October 1795 at Woolwich at a cost of £23,809. She was first commissioned under Captain Velters Berkley in August 1795 and sent to the Mediterranean to join the fleet under Sir John Jervis.

After the Battle of Cape St Vincent, Emerald was one of a number of vessels sent to look for the crippled Santisima Trinidad. In May 1798 she was separated from Horatio Nelson's squadron in a storm and thus was not present at the Battle of the Nile, arriving in Aboukir Bay nine days after. On 7 April 1800, Emerald was part of Rear-admiral John Thomas Duckworth's squadron which captured nine merchant vessels and two frigates in an action off Cadiz.

In 1803 Emerald served in the Caribbean as part of Samuel Hood's fleet, and took part in the invasion of St Lucia in July, and Surinam the following spring. She returned to home waters for repairs in 1806 and served in the western approaches. In 1809, Emerald was part of the fleet under Admiral James Gambier that fought the Battle of the Basque Roads. In November 1811 she was taken to Portsmouth and laid up in ordinary. She was fitted out as a receiving ship in 1822 then broken up in January 1836.

Construction

Emerald was a fifth-rate frigate of the Royal Navy. She was one of four Amazon class frigates, designed by William Rule and she, and her sister ship, Amazon, were ordered on 24 May 1794.[1] Both were 143 ft 2.5 in (43.650 m) along the gun deck, 119 ft 5.5 in (36.411 m) at the keel, and had a beam of 38 ft 4 in (11.68 m). With a depth in the hold of 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m),they were 933 67⁄94 (bm). The second pair of "Amazons" were marginally smaller at 925 87⁄94 (bm) and were built from Pitch Pine.[1] Emerald's initial build was completed at Thomas Pitcher's dockyard in Northfleet on 31 July 1795 at a cost of £14,419. She was immediately taken to Woolwich for fitting, which finished 12 October 1795, at a cost of a further £9,390.[1]

Career

Mediterranean service

Emerald was first commissioned in August 1795, under Velters Cornwall Berkley and in January 1797, she was sent to join Admiral John Jervis' fleet in the Mediterranean.[1] Although attached to Jervis' fleet at the time, Emerald did not take part in the Battle of Cape St Vincent, which occurred on 14 February, but was instead anchored in nearby Lagos Bay with a number of other vessels. On 16 February, the victorious British fleet and its prizes entered the bay and Emerald, Minerve, Niger, Bonne-Citoyenne and Raven were ordered to search for the Santisima Trinidad after she was seen being towed away from the battle.[1][2] The British squadron sighted Trinidad on 20 February, being towed by a large frigate and in the company of a brig, but did not engage. HMS Terpsichore, whilst cruising alone, later located the Santissima Trinidad and brought her to action but, being hopelessly outgunned, Terpsichore was forced to abandon her attack.[2] On 26 April, while on blockade at Cadiz, Emerald and the 74-gun Irresistible, captured a 34-gun Spanish ship and destroyed another.[3]

Action of 26 April 1797

Two Spanish vessels were sailing close to the coast when, at around 06:00 they were seen by Jervis' fleet. Emerald and the Irresistible, under Captain George Martin, gave chase.[4] The ships turned out to be the frigates Santa Elena and Ninfa, bound for Cadiz from Havana. During the previous night they had transferred their cargo of silver to a fishing boat that had warned them of the close proximity of the British fleet.[3] Having spotted the enemy pursuing them, the Spanish ships now sought shelter just north of Trafalgar in Conil Bay, the entrance of which was protected by a large rocky ledge which posed a threat to unwary seamen. Irresistible and Emerald successfully negotiated this obstacle at around 14.30, and engaged the Spanish anchored in the bay.[5][6] The action lasted until approximately 16.00 by which time both Spanish ships had surrendered. However, in order to avoid capture, Santa Elena cut her cable and drifted onto the shore where her crew escaped. The British managed to get the Santa Elena off but she had been too badly damaged and sank.[5][6] Irresistible and Emerald had captured Ninfa and destroyed Santa Elena but the cargo of silver was delivered safely to Cadiz.[3] The Spanish had eighteen men killed and thirty wounded whilst the British had one man killed and one wounded.[6] Ninfa was taken into British Service as HMS Hamadryad, a 36-gun frigate with a main battery of twelve pounders.[4][7]

Later in 1797, Captain Thomas Waller took command of Emerald. Under Waller she took part in the second bombardment of Cadiz, on 5 July, and then in the unsuccessful attack on Santa Cruz.[1][8]

Attack on Santa Cruz

Horatio Nelson's previously proposed attack on Santa Cruz, in April 1797, had to be aborted when 3,500 troops were redeployed. However, when Jervis heard that a Spanish treasure fleet was anchored there in July, the potential rewards of a success were too great to ignore.[9] Nelson was to take three ships of the line, three frigates, including Emerald, and 200 additional marines, and make an amphibious assault on the Spanish stronghold.[1][9] The frigates were to disembark their troops in boats, before engaging the batteries to the north-east but a combination of strong currents and heavy Spanish fire forced the British to abandon their attack. Between 22 and 25 July several attempts were made on the town and although troops were landed successfully, Spanish resistance was too strong and the British had to ask for an honourable withdrawal.[10]

After the attack, Nelson sent Emerald with his report to Jervis who in turn sent her on to England with dispatches. Waller arrived at the admiralty with the news, on 2 September.[11]

Alexandria

While serving on the Lisbon station and, while under the temporary command of Lord William Proby, in December 1797, Emerald captured the 8-gun privateer, Chassuer Basque.[1] In May 1798, Emerald accompanied Nelson, in Vanguard, with Orion, Terpsichore, and Bonne-Citoyenne to Alexandria. The squadron left Gibraltar on 9 May but Emerald became separated in a storm on 21 May. She was thus not present during the Battle of the Nile; arriving off Aboukir Bay on 12 August 1798.[12] Emerald remained stationed off Alexandria for the rest of the year. On 2 September, while on patrol in the company of Zealous, Goliath, Swiftsure, Seahorse, Alcmène, and Bonne-Citoyenne; she assisted in the destruction of Anemone, a four-gun, French cutter.[12]

Anenome, out of Malta, was chased inshore by Emerald and Seahorse, where she anchored in the shallow water, out of reach of the two British frigates. When boats were despatched, Anenome cut her anchor cable and drifted on to the shore. While attempting to escape, the French crew were captured by unfriendly Arabs, and stripped of their clothes, while those who resisted were shot. The commander and seven others escaped to the beach where they were rescued by the British, who had swum ashore with lines and wooden casks.[12]

Action on 18 June 1799

By the beginning of 1799, Emerald was back under the command of Captain Waller, serving as part of the advanced Mediterranean fleet.[1] While cruising with HMS Minerve on 2 June, they took Caroline, a 16-gun French privateer, off the south-east coast of Sardinia.[13][14] Later Emerald assisted in the capture of Junon, Alceste, Courageuse, Salamine and Alerte in the Action of 18 June 1799.[1][14] The British fleet, under George Elphinstone were some 69 miles off Cape Sicié, when three French frigates and two brigs were spotted. Elphinstone ordered three Seventy-fours; Centaur, Bellona and Captain, and two frigates; Emerald and Santa Teresa, to engage.[15] The chase lasted 28 hours so it was the next evening before the French ships were brought to action. The French squadron had become fragmented, enabling the British to take it piecemeal. The first shots were fired at 19:00 by Bellona, as she, Captain and the two frigates closed with Junon and Alceste, both of which struck immediately. Bellona then joined Centaur in her chase of Courageuse. Faced with the might of two Seventy-fours, Courageuse also surrendered. Emerald then overhauled Salamine, and Captain took Alerte at around 23:30.[14][16]

Action on 7 April 1800

In April 1800, Emerald was part of a small squadron blockading the port of Cadiz. The squadron, under Rear-admiral John Thomas Duckworth, also contained the 74-gun Leviathan, in which the admiral flew his flag, the 74-gun Swiftsure and a small fireship. On 5 April, the British squadron sighted a Spanish convoy comprising thirteen merchant vessels and three accompanying frigates, and at once gave chase.[17] It was not until 03:00 the following day however, that Emerald managed to overhaul and cross the bow of a 10-gunner, which immediately surrendered.[18] By daybreak the Spanish convoy had scattered and the only ship visible was a 14-gun brig; Los Anglese. Due to the lack of wind, boats from Leviathan and Emerald were sent after the brig which was subsequently captured after a short exchange of fire. Sails were by now spotted in the east, west and to the south, and the British were obliged to divide their force: Swiftsure went south, Emerald east, and Leviathan struck out westward.[17]

At midday, Emerald signalled that there were six sail to the north-east, and Leviathan wore round to pursue. By dusk, the two British ships had nine Spanish vessels in sight and in an attempt to intercept, set a new course northwards. Three ships were seen at midnight to the north-north-west and by 02:00 the following morning, two had been identified as enemy frigates.[19] Duckworth ordered a parallel course in anticipation of a dawn attack, and at first light, the British closed with their opponents, now identified as the frigates, Carmen and Florentina. The Spaniards, who in the darkness had assumed the British to be part of their convoy, now realised their mistake and set more sail in a bid to escape. Duckworth's request that the Spanish surrender was ignored so Leviathan fired into the rigging of the nearest frigate. Emerald opened up on the second frigate, disabling her after while, and just as Leviathan had positioned herself to fire into both at once, the Spanish surrendered.[20]

Emerald immediately set off after the third frigate, which was still visible, but was recalled by Duckworth and instead ordered to capture the merchant ships. This she did; securing four of the largest vessels before nightfall. Leviathan herself began a chase for the third frigate only after the other two had been made ready to sail, but by then it was too late and after four hours with the wind slackening, Leviathan gave up the pursuit. On her return to rendez-vous with Emerald, she managed to take a further enemy brig before night fell. The following day, Leviathan and Emerald sailed for Gibraltar with their prizes where they encountered the fireship, Incendiary, which had arrived the previous day with two captured vessels.[21] In all, the small British squadron, managed to secure nine merchant vessels and two frigates.[21][22]

Caribbean service

In June 1803, Emerald under Captain James O'Bryen, was attached to Samuel Hood's squadron in the Leeward Islands. Prior to the British invasion of St Lucia on 21st, Emerald was employed in the disruption of supplies to the island by harassing enemy shipping.[23] The invasion force left Barbados on 20 June and comprised Hood's flagship, Centaur, Courageux, Argo, Chichester, Hornet and Cyane. The following morning they were joined by Emerald and the 18-gun sloop, Osprey and by 11:00, the squadron was anchored in Choc Bay.[23][24] The troops were all landed by 17:00 and half an hour later the town of Castries was in the hands of the British.

The island's main fortress, Morne-Fortunée, refused to surrender and had to be stormed at 04:00 the following morning. By 04:30 on 22 July, the battle for St Lucia had been won and the British, having done so with such ease, decided to send a force to Tobago which capitulated on 1 July.[25]

On 24 June, Emerald captured the 16-gun French privateer, Enfant Prodigue between St Lucia and Martinique after a 72 hour chase. She was under the command of lieutenant de vaisseau Victor Lefbru and was carrying dispatches for Martinique.[23] The Royal Navy took her into service as HMS Santa Lucia; two French privateers recaptured her in 1807.

While in the company of HMS Heureux, on 10 August, Emerald intercepted and captured a Dutch merchant vessel travelling between Surinam and Amsterdam [26] On 5 September she captured two French schooners[27] then later that month, took part in attacks on Berbice, Essequibo and Demarara.[28]

Fort Diamond

Emerald's first lieutenant, Thomas Forest, commanded Fort Diamond on 13 March 1804 when, with thirty of Emerald's crew aboard, she captured a French privateer, off St Pierre, Martinique.[29] The privateer, Mosambique, was prevented from entering St Pierre by contrary winds and had sought shelter beneath the batteries at Seron.[30] Because Emerald was too far downwind, O'Bryen decide to make use of the 6-gun cutter Fort Diamond. Boats and crew from Emerald were used to provide a diversion and to draw some of the fire from the battery while Diamond approached from the opposite direction, rounded Pearl Rock, some two miles off the coast, and bore down on Mosambique.[29][30] Forest put the cutter alongside with such force that a chain, securing the privateer to the shore, snapped. The French crew of 60, abandoned their vessel and swam ashore.[30]

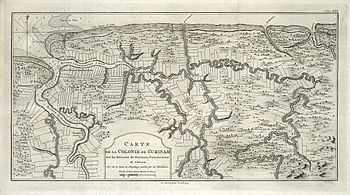

Capture of Surinam

In the spring of 1804, Emerald and her crew took part in an invasion of Surinam. A force consisting of Hood's flagship Centaur; Emerald, Pandour, Serapis, Unique, Alligator, Hippomenes and Drake, and 2,000 troops under Brigadier-General Sir Charles Green, arrived from Barbados on 25 April after a twenty-two day journey.[31][32] The sloop Hippomenes, a transport and a further three armed vessels, landed 700 troops, commanded by Brigadier-general Maitland, at Warapee Creek on the night of 30 April. The following night, O'Bryen was ordered to assist Brigadier-general Hughes in the taking Braam's Point. Emerald was at that time prevented from entering the Surinam River by a sandbar but O'Bryen forced her across on the rising tide and his example was followed by Pandour and Drake. Anchoring close by, the three British ships quickly put the Dutch battery of 18-pounders out of action and captured the fort without loss of life.[31][33]

Emerald and her companions then pushed up the river, sometimes in less water than the frigates drew, until they arrived close to the forts of Leyden and Frederici, on 5 May. A detachment of troops under Hughes was landed some distance away, and after marching undercover of the forests and swamps, launched an attack in which the two forts were quickly captured.[34] By this time most of the squadron had managed to work its way up the river as far as Frederici, Maitland was advancing along the Commewine River, and with troops poised to attack the fort of New Amsterdam, the Batavian commandant, Lieutenant-colonel Batenburg, duly surrendered.[35]

Service on the Home Station

Between February and June 1806, Emerald underwent repairs at Deptford dockyard before being recommissioned under Captain John Larmour.[1] The appointment was short-lived however, Emerald being taken over by Captain Frederick Lewis Maitland in the first quarter of 1807. While serving in the Basque Roads in April 1807, she captured the 14-gun privateer, Austerlitz. Emerald was escorting a Spanish poleacre that she had previously taken when, on the morning of 14 April, she spotted the privateer which she subsequently captured after a ten hour chase.[1][36]

Apropus

Boats from Emerald were used in a cutting out expedition in Vivero harbour on 13 March 1808. Whilst cruising inshore at around 17:00, Emerald spotted a large French schooner anchored there. Although it was late and despite having been seen by both the schooner and the harbour's batteries, plans were made to either capture or destroy her.[1][37] Maitland soon discovered it was not possible to place Emerald so as to simultaneously engage both the enemy batteries, which had commenced firing on his ship at around 17:30, and so the decision was taken to send parties ashore to silence the guns.[37]

The first, led by Lieutenant Bertram and accompanied by two marine lieutenants and two master mates, stormed the outer fort while Emerald took up a position as close to the second battery as the depth of water would allow. Another boat, under the command of the third lieutenant, Smith, landed about a mile from the target and was immediately met by Spanish soldiers who were subsequently driven off and pursued inland by the British. By the time this firefight had concluded, Emerald had silenced the battery, and it being so quiet and dark, Smith was unable to locate the fort.[37] Bertram, on the other hand, had accomplished his mission and had since walked round to rendez-vous with Midshipman Baird's party which had been sent to take possession of the schooner, which had run ashore after cutting its cable shortly after Emerald had entered the harbour. On the way Bertram had encountered sixty of the French crew whom he and his compatriots were obliged to disperse. The British made several attempts to refloat the schooner, which turned out to be the 250 ton, Apropus, but in the end were forced to make do with setting her on fire.[37]

Back in the Basque Roads

On 23 February 1809, Emerald was back in the Basque Roads in a squadron under Robert Stopford, in Caesar, which also contained Defiance, Donegal, Amethyst and Naiad.[38] At 20:00, while anchored off the Chassiron Lighthouse, to the north-west of Ile d'Oléron, the sighting of several rockets prompted Stopford to take his squadron and investigate. About an hour later, sails were seen to the east, which the British followed until daylight the following morning. The sails turned out to be those of a French squadron which Stopford deduced to be out of Brest and which hove to in the Pertuis d'Antioche.[38]

The French force comprised eight ship of the line and two frigates, and Stoppard immediately sent Naiad to appraise Admiral James Gambier of the situation. Naiad hadn't gone too far however when she signalled that there were three other sail to the north-west. Stoppard ordered Amethyst and Emerald to remain while he and the rest of the squadron set off in pursuit. The vessels sighted by Naiad were revealed to be three French frigates heading for Sable d'Olonne.[38] Stoppard's squadron encountered a British frigate, Amelia and a sloop, Doterel, which prompyly joined the chase. Shortly after, the French anchored and Caeser, Donegal, Defiance and Amelia stood in and engaged. Two of the French frigates were obliged to cut their cables and run ashore in order to escape before the British were forced to withdraw by the falling tide.[38] However, all three French frigates, Calypso, Italienne and Sybille, were destroyed in the action.[39]

Action of 5 April 1809

Emerald and Amethyst had more success in the spring of 1809 when, on 23 March 1809, they captured the brigs Caroline and Serpent, then in April Emerald assisted Amethyst in the capture a large 44-gun frigate off Ushant.[40][41] Niemen, with a main battery of 18-pounders and under the command of Captain Dupoter, was seen at 11:00 on 5 April by Emerald which immediately signalled Amethyst for assistance. Amethyst caught a glimpse of the French forty-four just as she turned away to the south-east and gave chase but by 19:20 had lost sight of both Niemen and Emerald. Amethyst's captain, Sir Michael Seymour, ordered a probable course of interception and fell in with Niemen again at around 21:30. Emerald however was not to be found and so Amethyst was compelled to engaged alone. Niemen was forced to strike when another British frigate, Arethusa came into view and fired her broadside.[41]

Later career

Emerald was part of the fleet under Admiral James Gambier that fought the Battle of the Basque Roads on 11 and 12 April 1809.[42] In July, Emerald took two French sloops, Deux Freres and Balance,[43] then on 8 October she rescued a British Brig when she captured Incomparable off the coast of Ireland. The brig was about to become a victim of the 8-gun French privateer when Emerald intervened.[44] On 6 November, still in Irish waters, Emerald took the 16-gun French brig, Fanfaron, two days out of Brest and bound for Guadeloupe.[45] In 1810, Emerald was still on the home station and captured the 350 ton burthen, Belle Etoile in the Bay of Biscay on 22 March. Caught after a twelve hour chase during which she jettisoned much of her cargo, the rather under-gunned privateer out of Bayonne, was pierced for twenty guns but only carried eight.[46] Emerald captured an American ship, Wasp, in July 1810; an 18-gun French privateer, Auguste, in April 1811.

Fate

In November 1811 Emerald was taken to Portsmouth and laid up in ordinary.[1][47] She was fitted out as a receiving ship in 1822 and then broken up in January 1836.[1]

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Winfield p.148

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 James (Vol.II) p.49

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Woodman p.99

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Clowes p.507

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 James (Vol.II) p.82

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 The London Gazette: no. 14010. p. 446. 16 May 1797. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ↑ James (Vol.II) p.83

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 14032. p. 717. 29 July 1797. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Heathcote p.181

- ↑ Heathcote p.182

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 14041. p. 835. 2 September 1797. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 The London Gazette: no. 15082. p. 1110. 20 November 1798. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 15162. p. 740. 23 July 1799. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 The London Gazette: no. 15162. p. 741. 23 July 1799. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ↑ James (Vol.II) p.262

- ↑ Troude p.164

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 James (Vol.III) p.37

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 15253. p. 421. 23 July 1799. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ James (Vol.III) pp.37 - 38

- ↑ James (Vol.III) p.38

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 The London Gazette: no. 15253. p. 422. 23 July 1799. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 15253. p. 423. 23 July 1799. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 The London Gazette: no. 15605. pp. 918–919. 26 July 1803. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ Clowes p.56

- ↑ James (Vol.III) p.207

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 15669. p. 109. 24 January 1804. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 15669. p. 110. 24 January 1804. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 16505. p. 1329. 16 July 1811. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 The London Gazette: no. 15697. p. 539. 28 April 1804. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 James (Vol.III) p.253

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 The London Gazette: no. 15712. pp. 761–762. 19 June 1804. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ James (Vol III) pp.288 - 289

- ↑ James (Vol.III) P.289

- ↑ James (Vol.III) pp.289 - 290

- ↑ James (Vol.III) p.290

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 16023. p. 533. 25 April 1807. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 The London Gazette: no. 16130. p. 416. 22 March 1808. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 The London Gazette: no. 16234. p. 289. 4 March 1809. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 16337. p. 139. 27 January 1810. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 16303. p. 1593. 3 October 1809. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 The London Gazette: no. 16246. p. 499. 11 April 1809. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 17458. p. 450. 9 March 1819. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 16352. p. 411. 17 March 1810. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 16310. p. 1708. 28 October 1809. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 16315. p. 1826. 14 November 1809. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 16357. p. 489. 31 March 1810. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 16548. p. 2341. 3 December 1811. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

References

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume IV. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- Heathcote, Tony (2005). Nelson's Trafalgar Captains and Their Battles. Leo Cooper Ltd. ISBN 978-1844151820.

- Henderson, James (2011). Frigates, Sloops and Brigs. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978 1 84884 526 8.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume II, 1797–1799. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-906-9.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume III, 1800–1805. London: Conway Martime Press. ISBN 0-85177-907-7.

- Troude, Onésime-Joachim (1867). Batailles navales de la France, Volume III. Challamel ainé.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. London: Seaforth. ISBN 1-86176-246-1.

- Woodman, Richard (2014) [2001]. The Sea Warriors – Fighting Captains and Frigate Warfare in the Age of Nelson. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978 1 84832 202 8.