Guru Granth Sahib

| Guru Granth Sahib | |

|---|---|

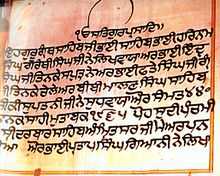

Illuminated Guru Granth Sahib folio with nisan (Mul Mantra) of Guru Gobind Singh. | |

| Predecessor | Guru Gobind Singh |

Guru Granth Sahib (Punjabi (Gurmukhi): ਗੁਰੂ ਗਰੰਥ ਸਾਹਿਬ, pronounced [ɡʊɾu ɡɾəntʰ sɑhɪb]) is the central religious text of Sikhism, considered by Sikhs to be the final, sovereign guru among the lineage of 11 Sikh Gurus of the religion.[1] It is a voluminous text of 1430 Angs (pages), compiled and composed during the period of Sikh gurus from 1469 to 1708[1] and is a collection of hymns (Shabad) or Baani describing the qualities of God[2] and the necessity for meditation on God's nām (holy name). Guru Gobind Singh (1666–1708), the tenth guru, after adding Guru Tegh Bahadur's bani to the Adi Granth,[3][4] affirmed the sacred text as his successor.[5] The text remains the holy scripture of the Sikhs, regarded as the teachings of the Ten Gurus.[6] The role of Guru Granth Sahib as a source or guide of prayer[7] is pivotal in Sikh worship. The Adi Granth, the first rendition, was first compiled by the fifth Sikh guru, Guru Arjun (1563–1606), from hymns of the first five Sikh gurus and 15 other great saints, or bhagats, including some from both Hindu and Muslim faiths.[2] Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Sikh guru, added all 115 of Guru Tegh Bahadur's hymns to the Adi Granth, and this second rendition became known as Guru Granth Sahib.[8] After the tenth Sikh guru died, Baba Deep Singh and Bhai Mani Singh prepared many copies of the work for distribution.[9]

It is written in the Gurmukhī script, in various dialects – including Lehndi Punjabi, Braj Bhasha, Khariboli, Sanskrit and Persian – often coalesced under the generic title of Sant Bhasha.[10]

History

| Part of a series on |

| Sikh scriptures |

|---|

|

| Guru Granth Sahib |

|

| Dasam Granth |

|

| Sarbloh Granth |

| Varan Bhai Gurdas |

|

During the guruship of Guru Nanak, collections of his hymns were compiled and sent to distant Sikh communities for use in morning and evening prayers.[11] His successor, Guru Angad, began collecting his predecessor's writings. This tradition was continued by the third and fifth gurus as well.

When the fifth guru, Guru Arjan, was collecting the writings of his predecessor, he discovered that pretenders to the guruship were releasing what he considered as forged anthologies of the previous gurus' writings and including their own writings alongside them.[12] In order to prevent spurious scriptures from gaining legitimacy, Guru Arjan began compiling a sacred book for the Sikh community. He finished collecting the religious writings of Guru Ram Das, his immediate predecessor, and convinced Mohan, the son of Guru Amar Das, to give him the collection of the religious writings of the first three gurus.[12] In addition, he sent disciples to go across the country to find and bring back any previously unknown writings. He also invited members of other religions and contemporary religious writers to submit writings for possible inclusion.[12] Guru Arjan selected hymns for inclusion into the book, and Bhai Gurdas acted as his scribe.

While the manuscript was being put together, Akbar, the Mughal Emperor, received a report that the manuscript contained passages vilifying Islam. Therefore, while travelling north, he stopped en route and asked to inspect it.[13] Baba Buddha and Bhai Gurdas brought him a copy of the manuscript as it then existed. After choosing three random passages to be read, Akbar decided that this report had been false.[13] He also granted a request from Guru Arjan to remit the annual tax revenue of the district because of the failure of the monsoon.[13]

In 1604 Guru Arjan's manuscript was completed and installed at the Harmandir Sahib with Baba Buddha as the first granthi, or reader. Since communities of Sikh disciples were scattered all over northern India, copies of the holy book needed to be made for them.[13] The sixth, seventh, and eighth gurus did not write religious verses; however, the ninth guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur, did. The tenth guru, Guru Gobind Singh, included Guru Tegh Bahadur's writings into the Guru Granth Sahib.[13]

In 1704 at Damdama Sahib, during a one-year respite from the heavy fighting with Aurengzeb which the Khalsa was engaged in at the time, Guru Gobind Singh and Bhai Mani Singh added the religious compositions of Guru Tegh Bahadur to Adi Granth to create a definitive version.[13] The religious verses of Guru Gobind Singh were not included in Guru Granth Sahib, but some of his religious verses are included in the daily prayers of Sikhs.[13] During this period, Bhai Mani Singh also collected Guru Gobind Singh's writings, as well as his court poets, and included them in a secondary religious volume, today known as the Dasam Granth Sahib This secondary text is not revered by the Sikhs, however, for whom only Guru Granth Sahib is Guru.[14]

Meaning and role in Sikhism

Sikhs consider the Guru Granth Sahib to be a spiritual guide not only for Sikhs but for all of mankind; it plays a central role in guiding the Sikhs' way of life. Its place in Sikh devotional life is based on two fundamental principles: that the text is the living Guru and that all answers regarding religion and morality can be discovered within it. Its hymns and teachings are called Gurbani or "Word of the guru" and sometimes Guru ki bani or "Word of God". Thus, in Sikh theology, the revealed divine word is written by the past Gurus. Numerous holy men, aside from the Sikh Gurus, are collectively referred to as Bhagats or "devotees."

Elevation of Adi Granth to Guru Granth Sahib

Punjabi: "ਸੱਬ ਸਿੱਖਣ ਕੋ ਹੁਕਮ ਹੈ ਗੁਰੂ ਮਾਨਯੋ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ"

Transliteration: "Sab sikhan kō hukam hai gurū mānyō granth"

English: "All Sikhs are commanded to take the Granth as Guru."

In 1708 Guru Gobind Singh conferred the title of "Guru of the Sikhs" upon the Adi Granth. The event was recorded in a Bhatt Vahi (a bard's scroll) by an eyewitness, Narbud Singh,[15] who was a bard at the Rajput rulers' court associated with gurus . variety of other documents also attest to this proclamation by the tenth Guru. Thus, despite some aberrations, Sikhs since then have overwhelmingly accepted Guru Granth Sahib as their eternal Guru.

Guru's commandment

A close associate of Guru Gobind Singh and author of Rehit-nama, Prahlad Singh, recorded the guru's commandment, saying: "With the order of the Eternal Lord has been established [Sikh] Panth: all the Sikhs hereby are commanded to obey the Granth as their Guru" (Rehat-nama, Bhai Prahlad Singh).[16] Similarly, Chaupa Singh, another associate of Guru Gobind Singh, has mentioned this commandment in his Rehat-nama.

Bhai Nand Lal, a court poet of Guru Gobind Singh, recorded the words of the guru in his writing "rehitnaama bhai nand laal" [17] as:

- ਜੋ ਮੁਝ ਬਚਨ ਸੁਣਨ ਕੀ ਚਾਇ,ਗ੍ਰ੍ਰ੍ਰੰਥ ਪੜੇ ਸੁਣੇ ਚਿੱਤ ਲਾਇ ॥ (੧੯)

- ਮੇਰਾ ਰੂਪ ਗੰ੍ਰ੍ਥ ਜੀ ਜਾਣ,ਇਸ ਮੇਂ ਭੇਤ ਨਹੀਂ ਕੁਝ ਮਾਨ ॥ (੨੦)

- jō mujh bacan suṇan kī cāi, grrra°th pad̲ē suṇē ciੱt lāi || (19)

- mērā rūp ga°`rrath jī jāṇ, is mēṃ bhēt nahīṃ kujh mān || (20)

- "Those who aspire to listen to my sermons diligently should read and recite the Guru Granth Sahib Ji." (19)

- "Deem the Granth Ji as my embodiment, and concede to no other perception." (20)

Composition

The Sikh Gurus spoke Punjabi and developed a new writing script, Gurmukhī, for writing their sacred hymns.[18] Although the exact origins of the script are unknown,[19] it is believed to have existed in an elementary form during the time of Guru Nanak. According to Sikh tradition and the Mahman Prakash, an early Sikh manuscript, Guru Angad invented the script at the suggestion of Guru Nanak during the lifetime of the founder.[18][20] The word Gurmukhī translates as "from the mouth of the Guru". It was used from the outset for compiling Sikh scriptures. The Sikhs assign a high degree of sanctity to the Gurmukhī script;[21] it is the official script for the Indian State of Punjab.

Guru Granth Sahib is divided by musical settings or ragas[22] into 1,430 pages known as Angs (limbs) in Sikh tradition. It can be categorized into two sections:

- Introductory section consisting of the Mul Mantra, Japji and Sohila, composed by Guru Nanak;

- Compositions of Sikh gurus, followed by those of the bhagats who know only God, collected according to the chronology of ragas or musical settings (see below).

The word raga refers to the "color"[23] and, more specifically, the emotion or mood produced by a combination or sequence of pitches.[24] A raga is composed of a series of melodic motifs, based upon a definite scale or mode of the seven Swara psalmizations,[25] that provide a basic structure around which the musician performs. Some ragas may be associated with times of the day and year.[22] There are 31 ragas in the Sikh system, divided into 14 ragas and 17 raginis (minor or less definite ragas). Within the raga division, the songs are arranged in order of the Sikh gurus and Sikh bhagats with whom they are associated.

The ragas are, in order: Sri, Manjh, Gauri, Asa, Gujri, Devagandhari, Bihagara, Wadahans, Sorath, Dhanasri, Jaitsri, Todi, Bairari, Tilang, Suhi, Bilaval, Gond (Gaund), Ramkali, Nut-Narayan, Mali-Gaura, Maru, Tukhari, Kedara, Bhairav (Bhairo), Basant, Sarang, Malar, Kanra, Kalyan, Prabhati and Jaijawanti. In addition there are 22 compositions of Vars (traditional ballads). Nine of these have specific tunes, and the rest can be sung to any tune.[22]

Authors

Following is list of authors whose Hymns are present in Guru Granth Sahib:

- Kabir

- Ravidas

- Namdev

- Bhagat Beni

- Bhagat Bhikhan

- Bhagat Dhanna

- Jayadeva

- Bhagat Parmanand

- Bhagat Pipa

- Ramananda

- Bhagat Sadhana

- Bhagat Sain

- Surdas

- Bhagat Trilochan

- Guru Nanak

- Guru Angad

- Guru Amar Das

- Ramkali Sadu

- Fariduddin Ganjshakar

- Guru Ram Das

- Guru Arjan

- Satta Doom

- Balvand Rai

- Bhatt Kalshar

- Bhatt Balh

- Bhatt Bhalh

- Bhatt Bhika

- Bhatt Gayand

- Bhatt Harbans

- Bhatt Jalap

- Bhatt Kirat

- Bhatt Mathura

- Bhatt Nalh

- Bhatt Salh

- Guru Tegh Bahadur

Sanctity among Sikhs

No one can change or alter any of the writings of the Sikh gurus written in the Adi Granth. This includes sentences, words, structure, grammar and meanings. Following the example of the gurus themselves, Sikhs observe total sanctity of the text of Guru Granth Sahib. Guru Har Rai, for example, disowned one of his sons, Ram Rai, because he had attempted to alter the wording of a hymn by Guru Nanak.[26] Guru Har Rai had sent Ram Rai to Delhi in order to explain Gurbani to the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb. To please the Emperor he altered the wording of a hymn, which was reported to the guru. Displeased with his son, the guru disowned him and forbade his Sikhs to associate with him or his descendants.

Translations

Translations of Guru Granth Sahib are available. Sikhs reject the concept of a sacred language and believe that Guru Granth Sahib can be accessed in many languages.[27]

Recitation

Guru Granth Sahib is always the focal point in any Gurudwara, being placed in the centre on a raised platform known as a Takht (throne), while the congregation of devotees sits on the floor and bow before the Guru as a sign of respect. Guru Granth Sahib is given the greatest respect and honour. Sikhs cover their heads and remove their shoes while in the presence of this sacred text. Guru Granth Sahib is normally carried on the head and as a sign of respect, never touched with unwashed hands or put on the floor.[28] It is attended with all signs of royalty, with a canopy placed over it. A chaur sahib is waved above the book. Peacock-feather fans were waved over royal or saintly beings as a mark of great spiritual or temporal status; this was later replaced by the modern Chaur sahib.

The Guru Granth Sahib is taken care of by a Granthi, who is responsible for reciting from the sacred text and leading Sikh prayers. The Granthi also acts as caretaker for the Guru Granth Sahib, keeping the book covered in clean cloths, known as rumala, to protect from heat, dust, pollution, etc. The Guru Granth Sahib rests on a manji sahib under a rumala until brought out again.[28]

Printing

The editing of Guru Granth Sahib is done by the official religious body of Sikhs based in Amritsar. Great care is taken while making printed copies and a strict code of conduct is observed during the task of printing.[29] Before the late nineteenth century, only handwritten copies were prepared. The first printed copy of the Guru Granth Sahib was made in 1864. Since the early 20th century, it has been printed in a standard edition of 1430 Angs. Any copies of Guru Granth Sahib deemed unfit to be read from are cremated, with a ceremony similar to that for cremating a deceased person. Such cremating is called Agan Bheta. Guru Granth Sahib is currently printed in an authorized printing press in the basement of the Gurudwara Ramsar in Amritsar, with misprints and set-up sheets being cremated at Goindval.[30]

Punjab Digital Library, in collaboration with the Nanakshahi Trust, began digitization of centuries-old manuscripts in 2003.

Quotes

Max Arthur Macauliffe writes about the authenticity of the scriptures:

- The Sikh religion differs as regards the authenticity of its dogmas from most other theological systems. Many of the great teachers the world has known, have not left a line of their own composition and we only know what they taught through tradition or second-hand information. If Pythagoras wrote of his tenets, his writings have not descended to us. We know the teachings of Socrates only through the writings of Plato and Xenophon. Buddha has left no written memorial of his teaching. Kungfu-tze, known to Europeans as Confucius, left no documents in which he detailed the principles of his moral and social system. The founder of Christianity did not reduce his doctrines to writing and for them we are obliged to trust to the gospels according to Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The prophet Muhammad did not himself reduce to writing the chapters of the Quran. They were written or compiled by his adherents and followers. But the compositions of Sikh Gurus are preserved and we know at first hand what they taught.

Pearl Buck gives the following comment on receiving the First English translation of Guru Granth Sahib:

- I have studied the scriptures of the great religions, but I do not find elsewhere the same power of appeal to the heart and mind as I find here in these volumes. They are compact in spite of their length, and are a revelation of the vast reach of the human heart, varying from the most noble concept of God, to the recognition and indeed the insistence upon the practical needs of the human body. There is something strangely modern about these scriptures, and this puzzled me until I learned that they are in fact comparatively modern, compiled as late as the 16th century, when explorers were beginning to discover that the globe upon which we all live is a single entity divided only by arbitrary lines of our own making. Perhaps this sense of unity is the source of power I find in these volumes. They speak to a person of any religion or of none. They speak for the human heart and the searching mind.[31]

Message

Some of the major messages can be summarized as follows: -

- One God for all.

- Everyone is equal, including women are equal to men.

- Speak and live truthfully.

- Control the five vices.

- Live in God's hukam (will/order).

- Practice humility, kindness, compassion, love, etc.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Keene, Michael (2004). Online Worksheets. Nelson Thornes. p. 38. ISBN 0-7487-7159-X.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Penney, Sue. Sikhism. Heinemann. p. 14. ISBN 0-435-30470-4.

- ↑ Ganeri, Anita (2003). Guru Granth Sahib and Sikhism. Black Rabbit Books. p. 13.

- ↑ Kapoor, Sukhbir (2005). Guru Granth Sahib an Advance Study. Hemkunt Press. p. 139.

- ↑ Partridge, Christopher Hugh (2005). Introduction to World Religions. p. 223.

- ↑ Kashmir, Singh. Sri Guru Granth Sahib — A Juristic Person. Global Sikh Studies. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ↑ Singh, Kushwant (2005). A history of the sikhs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-567308-5.

- ↑ Kapoor, Sukhbir. Guru Granth Sahib an Advance Study. Hemkunt Press. p. 139. ISBN 9788170103219.

- ↑ Pruthi, Raj (2004). Sikhism And Indian Civilization. Discovery Publishing House. p. 188.

- ↑ Harnik Deol, Religion and Nationalism in India. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0-415-20108-X, 9780415201087. Page 22. "Remarkably, neither is the Qur'an written in Urdu language, nor are the Hindu scriptures written in Hindi, whereas the compositions in the Sikh holy book, Adi Granth, are a melange of various dialects, often coalesced under the generic title of Sant Bhasha."

The making of Sikh scripture by Gurinder Singh Mann. Published by Oxford University Press US, 2001. ISBN 0-19-513024-3, ISBN 978-0-19-513024-9 Page 5. "The language of the hymns recorded in the Adi Granth has been called Sant Bhasha, a kind of lingua franca used by the medieval saint-poets of northern India. But the broad range of contributors to the text produced a complex mix of regional dialects."

Surindar Singh Kohli, History of Punjabi Literature. Page 48. National Book, 1993. ISBN 81-7116-141-3, ISBN 978-81-7116-141-6. "When we go through the hymns and compositions of the Guru written in Sant Bhasha (saint-language), it appears that some Indian saint of 16th century...."

Introduction: Guru Granth Sahib. "Guru Granth Sahib Ji is written in Gurmukhi script. The language, which is most often Sant Bhasha, is very close to Punjabi. It is well understood all over northern and northwest India and is popular among the wandering holy men. Persian and some local dialects have also been used. Many hymns contain words of different languages and dialects, depending upon the mother tongue of the writer or the language of the region where they were composed."

Nirmal Dass, Songs of the Saints from the Adi Granth. SUNY Press, 2000. ISBN 0-7914-4683-2, ISBN 978-0-7914-4683-6. Page 13. "Any attempt at translating songs from the Adi Granth certainly involves working not with one language, but several, along with dialectical differences. The languages used by the saints range from Sanskrit; regional Prakrits; western, eastern and southern Apabhramsa; and Sahiskriti. More particularly, we find sant bhasha, Marathi, Old Hindi, central and Lehndi Panjabi, Sgettland Persian. There are also many dialects deployed, such as Purbi Marwari, Bangru, Dakhni, Malwai, and Awadhi."

Harjinder Singh, Sikhism. Guru Granth Sahib (GGS). "Guru Granth Sahib Ji also contains hymns which are written in a language known as Sahiskriti, as well as Sant Bhasha; it also contains many Persian and Sanskrit words throughout." - ↑ Singh, Khushwant (1991). A history of the Sikhs: Vol. 1. 1469-1839. Oxford University Press. p. 34. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Singh, Khushwant (1991). A history of the Sikhs: Vol. 1. 1469-1839. Oxford University Press. pp. 54–56,294–295. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Singh, Khushwant (1991). A history of the Sikhs: Vol. 1. 1469-1839. Oxford University Press. pp. 54–55,90,148,294–296. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ McLeod, W. H. (1990-10-15). Textual sources for the study of Sikhism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226560854. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ↑ Singh, Gurbachan; Sondeep Shankar (1998). The Sikhs : Faith, Philosophy and Folks. Roli & Janssen. p. 55. ISBN 81-7436-037-9.

- ↑ Singh, Ganda; Gurdev Singh (199676767676). Perspectives on The Sikh Tradition. Singh Brothers, Amritsar (India). p. 224121211212121212129. ISBN 81-7205-178-6. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ rehitnaam bhai nand lal http://www.searchgurbani.com/bhai_nand_lal/rahitnama/page/40

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hoiberg, Dale; Indu Ramchandani (2000). Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan. p. 207. ISBN 0-85229-760-2.

- ↑ Duggal, Kartar Singh (1998). Philosophy and Faith of Sikhism. Himalayan Institute Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-89389-109-6.

- ↑ Gupta, Hari Ram (2000). History of the Sikhs Vol. 1; The Sikh Gurus, 1469-1708. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers (P) Ltd. p. 114. ISBN 81-215-0276-4.

- ↑ Mann, Gurinder Singh (2001). The making of Sikh Scripture. Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-19-513024-3.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Brown, Kerry (1999). Sikh Art and Literature. Routledge. p. 200. ISBN 0-415-20288-4.

- ↑ Giriraj, Ruhel (2003). Glory Of Indian Culture. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. p. 96. ISBN 9788171825929.

- ↑ The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2. Routledge. 2013. p. 935. ISBN 9781136096020.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Amrita, Priyamvada (2007). Encyclopaedia of Indian music. p. 252. ISBN 9788126131143.

- ↑ Bains, K.S. "A tribute to Bal Guru". The Tribune.

- ↑ http://www.sikhs.org/english/frame.html

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Fowler, Jeaneane (1997). World Religions:An Introduction for Students. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 354–357. ISBN 1-898723-48-6.

- ↑ Jolly, Asit (2004-04-03). "Sikh holy book flown to Canada". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- ↑ Eleanor Nesbitt, "Sikhism: a very short introduction", ISBN 0-19-280601-7, Oxford University Press, pp. 40-41

- ↑ Foreword to the English translation of Guru Granth Sahib Ji by Gopal Singh, 1960

Further reading

- Guru Granth Sahib (English Version) by Dr Gopal Singh M.A Ph.D., Published by World Book Centre in 1960

- Singh, Sahib (Prof) (1996). About The Compilation of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji Amritsar: Lok Sahit Parkashan.

- Dilgeer, Harjinder Singh (2010), Spiritual Manifesto of the World: Guru Granth Sahib, publisher Sikh University Press & Singh Brothers Amritsar, 2010.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Guru Granth Sahib |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Videos

Audio

Text

- English translation of the Guru Granth Sahib Ji (PDF)

- The Guru Granth Sahib in Unicode format

- Granth Sahib.com

- Download Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji in Spanish / Español (doc)

- The "Oficial Translations of Siri Guru Granth Sahib in Spanish".Revised / PDF

- Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji(Gurmukhi) PDF

- Search Guru Granth Sahib in English, Gurmukhi and 52 other languages

Other

| Preceded by Guru Gobind Singh |

Sikh Guru Guru Granth Sahib is the eternal and final living Guru |

Succeeded by - |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||