Gulper shark

| Gulper shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Squaliformes |

| Family: | Centrophoridae |

| Genus: | Centrophorus |

| Species: | C. granulosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Centrophorus granulosus (Bloch & J. G. Schneider,1801) | |

| |

| Range of gulper shark (in blue) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Centrophorus acus Garman, 1906 | |

The gulper shark (Centrophorus granulosus) is a long and slender dogfish usually about three feet in length generally found in deep, murky waters all around the world. It is a light grayish brown, paler ventrally, with a long snout and large greenish eyes.[1] This deep water shark has two dorsal fins with long, grooved spines and the second dorsal fin smaller than the first. Its upper teeth are blade-like and lower have finely serrated edges.[1] This tertiary consumer feeds on mainly fishes such as bony fishes, but also cephalopods such as squid and other invertebrates like crustaceans.[1] The gulper shark is currently a vulnerable species mainly because of exploitation by humans and their abnormally long gestation period and low fecundity, preventing their population from recovering.[2]

Development and Reproduction

Gulper sharks reach maturity at around age 12 to 16 years for females, and age 7 to 8 years for males.[3] The maturity of a gulper shark can be determined by the seven-stage maturity scale for aplacental and placental viviparous sharks.[4] This scale is good for practical field use, but may not be as accurate as other maturity scales that have more than seven stages. Maturity for gulper sharks is considered when they are at stage 3 or above, which for males is when gonads are enlarged and filled with sperm, and sperm ducts are tightly coiled. For females, stage three is when ovaries are large and well rounded.[4]

On average, male gulper sharks are smaller than females.[5] The size of an average adult male is 80 to 95 cm. The size of an average adult female is from 90 to 100 cm long.[5] Differences in size between the sexes may be due to the need for space to support offspring.[5] It has been hypothesized that gulper sharks display a “depth distribution pattern associated with size” based on random human observation.[5]

Male gulper sharks tend to outnumber females 2:1, which is common for many fish species. The life expectancy, longevity, of female gulper sharks ranges between 54 and 70 years.[5] Having a long life expectancy but a low net reproduction rate suggests that the population of gulper sharks would be at a very high risk if too many of them were killed from excessive fishing.

Female gulper sharks typically have between 2 to 10 pups in their lifetime, with generally one pup per pregnancy, this is considered to be a low fecundity.[5] Once fertilized, females can hold up to 6 mature egg cells, or oocytes, in their body at a time. The length of time these egg cells are kept inside the female’s body is called the gestation period. Gulper sharks have a long gestation period, around two years.[2] Gulper sharks can have long resting periods between pregnancies.[1]

They are ovoviviparous, meaning the only parental care they give their young is during the incubation period.[4] Since not all oocytes form into pups, when a pup or two is formed inside the female, they eat the remaining fertilized eggs, known as oophagy.[1] After they are born, they are on their own. Having a low fecundity, a long gestation period, breaks between pregnancies, and a late age of maturity all contribute to the gulper shark having a very low net reproduction rate.[1] It is believed that the gulper shark has the lowest reproduction rate of any elasmobranch species.[1]

Geographic Range

The gulper shark is a deepwater oceanic species, living in waters ranging between 100 to 1490 meters in depth,[2] with the juveniles being the main occupant of the lower half of the depths.[6] Acceptable habitats for gulper populations are found globally, wherever temperate and tropical waters are found. The gulper shark is most commonly found in the 300 to 800 meter depth range, inhabiting the upper continental slopes and outer continental shelves,[2] the gulper is highly migratory species and has schooling habits based on multiple sharks being present around baited cameras.[7]

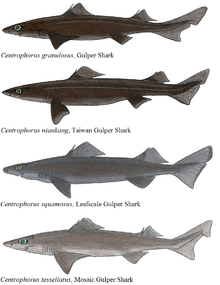

Due to the frequency and patterns of migration the gulper shark population estimates may be inaccurate with some sharks being counted twice, which are exacerbated by inappropriate tagging techniques. There are multiple species of gulper sharks, which has contributed to misidentification in the past. For example, populations of the gulper shark in the Southeast Atlantic Ocean may represent a separate species.[2] Therefore, taxonomic confusion may influence current geographical range.

Human Interaction

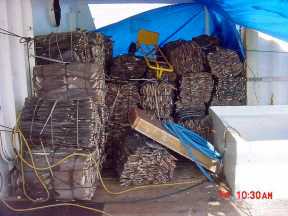

Fishing and Bycatch

Human interaction with the gulper shark exists mainly in the form of fishing. Longline fishing is a typical method for fishing at the depth required to catch gulper sharks, and the broad distribution of gulper habitat leads to this method being used to catch gulpers around the world. However, gulper sharks are not always caught intentionally. The deep waters in which the gulper and similar shark species live is difficult to harvest, and longlines are an unspecific form of fishing. Longlines intended for other species can easily catch gulper sharks.[8]

When a fish species other than the intended catch is caught, it is called bycatch. Although bycatch is not always a significant cause of loss to population size, it highlights the unpredictable nature of deepwater fish exploitation 19.[9] Rules and regulations regarding bycatch treatment are difficult to enforce by the nature of the bycatch being unintentional. Bycatch is often not treated as a serious issue until a species has declined to a point where small bycatch has a large effect, so data on the effect of bycatch on gulper populations is not abundant. Gulper shark populations have dropped as much as 80% in some areas, so bycatch is only recently becoming a big issue for them.[2]

Consumables

The reasons why the gulper shark would be harvested are just as important as how it is harvested. Gulper sharks do not constitute any particular resource that is not common to most deepwater sharks. Fins and meat are two components generally taken from them, but are also those harvested from any other shark. It is the liver oil at which the gulper shark presents a harvesting advantage. Compared to similar species such as the dogfish shark, the gulper has a larger liver with more oil. Traditionally, shark oil is a folk remedy for a variety of ailments, but also has been shown to contain compounds of contemporary medicinal value, most notable squalene, although the compound can also be extracted from plants.[10] This compound makes the liver of the gulper shark very valuable and is a large part of gulper-specific fishing.

Ecology

Life History

The life history of an organism describes the timing of important events for the typical individual of a species. The life history of the gulper shark shows that vulnerability to harvesting is inherent in its biology. The slow rate of gulper growth and development leads to a life strategy that is more centered on competition with one another than escaping predation, especially from humans. This is demonstrated from even the earliest part of an individual gulper's life history where it consumes other fertilized eggs inside its parent's body.[1]

A long gestation period, later maturity, and long lifespan all contribute to a K-selected tendency that favors intraspecific competition, or competition with similar species, over survival defenses having to do with predation. Harvesting is a form of predation that slow, invested reproduction does not easily alleviate. The long gestation, low fecundity, and breaks in individual reproduction lead to slow repopulation ability.[1] Slow reproduction is a part of the species biology, and cannot be changed in one generation based on sudden predation pressure. A group of gulper sharks that undergoes predation by humans may take fifteen years or longer to recover, if at all, based on their maturation time of twelve to sixteen years.[3] Large populations of gulper sharks must be built over long periods of time.

Gulper life strategy is also consistent with their trophic level and place in the deepwater community. They are tertiary consumers with no apparent predators, so their biological gear toward competition is an ecologically sound strategy.[11] The introduction of human interaction with gulper sharks is the introduction of a higher trophic level, and presents a relationship that current gulper biology is not equipped to handle while maintaining steady or growing population size.

While the fishing of gulper sharks and utilization of squalene from their livers is not inherently an activity that drives them toward extinction, overexploitation of the species can be a problem. The status of gulper sharks on the ICUN red list is currently only vulnerable rather than endangered.[2] The squalene taken from the gulper liver is in high demand as a possible cancer therapy component among other uses, leading to unchecked harvesting of the species. When the populations are declining due to overexploitation, each viable individual is important. As much as 80% of the gulper population has been depleted in some areas, so any harvesting can have a large effect on the decline of the species or possible recovery.[2]

The key to overexploitation in gulper sharks is that they require nearly as much time as humans to mature and reproduce. Their life strategy indicates that the frame of view for gulper fishing plans needs to be based on longer amounts of time, to allow for the consideration of the next generation of individuals. Gulper shark do not mature much faster than humans, so they need to be exploited based on a schedule that reflects this. However, being harvested by a species with similar growth patterns means that the gulper shark is unlikely to be considered in this way. It is highly susceptible to overexploitation leading to widespread population decline and its status and a species vulnerable to endangerment.

Conservation Efforts / Legislation

The gulper shark has been classified as vulnerable status by the IUCN since 2000 due to heavy overfishing and exacerbated through bycatch and low reproductive rates. The General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM), which is in charge of almost all intergovernmental fishery management decisions, mandated in 2005 to stop expanding deep water fishing beyond 1,000 meters.[12] This mandate however, does not support the main population of gulper sharks, which generally live 300–800 meters below the surface. This decision also does not stop any current deepwater fishing; it simply stops any further expansion.[2] This is an insufficient conservation attempt, as it does not help gulper populations under stress, it simply stops more stress from accumulating. The current level of fishing may already be enough to render that population critically endangered in that region, especially considering the low reproductive rate of gulpers.

Other areas of gulper shark populations have no current regulations. The Northwest Atlantic Ocean currently has no rules in regard to the harvesting of gulper sharks, and has already seen a decrease in gulper population of 80-95% since 1990.[13]

While not many laws apply to gulper sharks specifically, some blanket laws covering many different species have been created. The United States Government passed the Shark Conservation Act in 2010, which prohibited removing fins from sharks that were usually caught as bycatch and then sold to Chinese markets for shark fin soup. This law seals many of loopholes by requiring that any fins or tails brought to land must be “naturally attached to the corresponding carcass” and that no U.S. ship in foreign waters is allowed to possess shark fins.[11] This act protects all species of sharks within 50 nautical miles of the U.S. coast.[11] This is a much more effective law than that by the GFCM, because it addresses shark finning directly and cuts down on the amount of gulpers killed for their fins. Since this law point-blank cuts down on bycatching, it should be an effective effort at the conservation of shark species off U.S. coasts.

Issues for Effective Conservation

While conservation attempts are being made, certain issues like fishery guidelines and catch verification pose problems for furthering conservation attempts.

The fisheries concept is a closely regulated way to harvest gulpers, while monitoring the species population to ensure it does not crash. They generally use body mass as an indicator of when to harvest the sharks to allow growth of the population. When these ratios are incorrect, the fishery can easily crash because sharks are harvested before they can reproduce. This is especially true with the gulper shark, which has a two-year-long gestational period and a twelve to sixteen year maturity for females. Biery and Daniel Pauly from UBC Fisheries Centre in Canada executed a review on species-specific fin to body-mass ratios in 2012. Their paper concludes that current regulated ratios are not appropriate for all species and that regulations based off a general ratio for all species is inadequate and may be harming fisheries. The ratios used by many fisheries were originally compiled by a politically affiliated group called The Regional Fishery Management Organizations, RFMO. Biery and Pauly collected fin to body-mass ratios for 50 different species and eight different countries and observed that actual fin to body-mass ratios varied by species and location. Species specific mean ratios ranged from 1.1% to 10.9% and estimated mean ratios by country ranged from 1.5% to 6.1% indicating that current regulations will crash fisheries and not promote population growth [14]

Away from the commercial side of conservation, there are tagging efforts to monitor gulper populations. Tagging is a common ecological tool to study the species characteristics. A large problem with monitoring the populations of Australian and Indonesian dogfish is that discriminating between the seven local species by morphological attributesalone is unreliable. In 2012 a study conducted by Ross Daley, Sharon Appleyard, and Matthew Koopman from the CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research Center in Hobart, Australia aims to help monitored recovery plans by implementing a new catch data verification plan. Their study focuses on using the 16s mitochondrial gene region to differentiate these species and when sequenced, all but C. harrissoni and C. isodon were distinguishable.[15] They concluded that 16s gene is a strong marker suitable for fishery catch verification and that using this technique is a reliable and efficient system for routine testing. However, specialized primers needed for trials are sensitive to decay. Therefore, preservation problems need to be researched to further the prospective use of a 16s mitochondrial classification. This system for routine testing is only available to scientists and would require substantial training for fishermen to be able to use this technique.[15]

Uncertainties and Inconsistency in Data

While information concerning gulper sharks exists, there is no place to centrally compile the information so that other researchers may easily obtain it. This leads to repetition in basic data and less depth into the subject matter. Information presented may also be inaccurate as many genus of Centrophorus are morphologically similar. While attempts are being made to make it easier to identify different genus, such as Daley’s use of 16s mitochondrial DNA listed above,[15] older data listed for gulper sharks could be for ones other than the granulosus, such as the dumb gulper shark. This also means that current populations numbers could account for other dogfish than just the gulper sharks. Lastly, due to the frequency and patterns of migration, the recorded gulper shark populations may be inaccurate.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 ARKive, “Gulper Shark Fact File”, “[www.arkive.org/gulper-shark/centrophorus-granulosus]”, 3/21/2013

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Guallart, Serena, Mancusi, Casper, Burgess, Ebert, Clarke, Stenberg, “IUCN Red List of Threatened Species”, 2006, “[www.iucnredlist.org]”, 1 March 2013

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Clarke, Connolly, Bracken, “Journal of Fish Biology”, 4 Apr 2015, “”, 3/20/2013

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 MedSudMed, “FAO Sicily”, Dec 2008, “”, 3/21/2013

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Severino, Afonso-Dias, Delgado, “Life and Marine Sciences 26: 57-61”, 2009, “[www.horta.uac.pt/intradop/images/stories/arquipelago/26/57-61_Severino_etal_09_ARQ26.pdf]”, 3/20/2013

- ↑ Guallart, “Tesis doctoral, Universitat de Valencia”, 1998, “”, 4/17/13

- ↑ Gilat, Gelman, “Fisheries Research Amsterdam 2(4): 257-271”, 1984, “”, 4/17/13

- ↑ “Seafood Watch”, Fishing Methods Fact Card, “”, 4/18/13 April

- ↑ Hogan, Michael, 2010, “Overfishing”, [“http://www.eoearth.org/article/Overfishing?topic=49521”], eds. Sidney Draggan and C.Cleveland. Washington DC.

- ↑ National Geographic [“http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2009/12/091229-sharks-liver-oil-swine-flu-vaccine/]

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 ”US Shark Conservation Act of 2010”, 2010, “”, 3/26/2013

- ↑ “ICES WGFE”, 2006, “[www.artsdatabanken.no/ICES_WGFE_08_rapport_cU3hd.pdf.file]”, 4/10/2013

- ↑ “GFCM”, 2005, “”, 4/10/2013

- ↑ Pauly: Biery, “Journal of Fish Biology 80 (5), 2012, “[ doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2011.03215.x.]”, 3/14/2013

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Daley:Appleyard:Koopman, “Marine and Freshwater Research CSIRO Publishing. 63, 708-714”, 2012, “”, 3/14/2013