Gruban v Booth

Gruban v Booth was a 1917 fraud case in England that generated significant publicity because the defendant, Frederick Handel Booth, was a Member of Parliament. Gruban was a German-born businessman who ran several factories that made tools for manufacturing munitions for the First World War. In an effort to find money to expand his business he contacted a businessman and Member of Parliament named Frederick Handel Booth, who agreed to provide the necessary money. After stealing money Booth tricked Gruban into handing over the company and then had him interned under war-time regulations to prevent the story coming out.

Gruban successfully appealed against his internment, and as soon as he was freed brought Booth to court. The case was so popular that the involved barristers found it physically difficult to get into the court each day due to the size of the crowds gathered outside. Although the barristers on both sides were noted for their skill the case went almost entirely one way, with the jury taking only ten minutes to find Booth guilty. This was one of the first noted cases of Patrick Hastings, and his victory in it led to him applying to become a King's Counsel.

Background

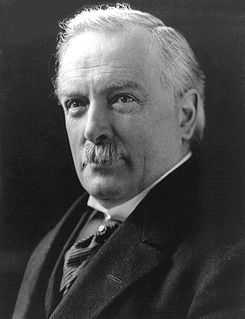

John Gruban was a German-born businessman, originally named Johann Wilhelm Gruban, who had come to England in 1893 to work for an engineering company, Haigh and Company.[1] By 1913 he had turned the business from an almost bankrupt company to a successful manufacturer of machine tools, and at the outbreak of the First World War it was one of the first companies to produce machine tools used to make munitions.[1] This made Gruban a major player in a now-large market, and he attempted to raise £5,000 to expand his business.[1] On independent advice he contacted Frederick Handel Booth, a noted Liberal Member of Parliament who was chairman of the Yorkshire Iron and Coal Company and had led the government inquiry into the Marconi scandal.[2] When Gruban contacted Booth, Booth told him that he could do "more for [your] company than any man in England", claiming that David Lloyd George (at the time Minister of Munitions) and many other important government officials were close friends.[2] With £3,500 borrowed from his brother-in-law, Booth immediately invested in Gruban's company.[2]

The sinking of the RMS Lusitania in 1915 created a wave of anti-German sentiment, and Gruban worried that he would find it difficult to find government work because of his nationality and thick German accent.[2] He again contacted Booth, who again claimed to be friends with David Lloyd George and his secretary, Christopher Addison, and said that if Gruban put Booth on the Board of Directors he could "do with the Ministry of Munitions what I like".[2] Gruban immediately made Booth the chairman of his company, and over 3 months took £400 on expenses.[2] He then claimed that this was not enough money for the work he did, and he should get a secret payment of 10% of the value of a contract known as the "Birmingham Contract".[2] The contract was worth £6,000, and Booth wrote a memo saying that he should have £580 or £600. Gruban refused, and Booth threw the note in the wastepaper basket.[3] From that point onwards Booth worked as hard as he could to undermine Gruban's position, while outwardly appearing to be his friend.[3]

Over the next few months a series of complaints came from the Ministry of Munitions about Gruban's work and his German origins, ending in a written statement by David Lloyd George's private secretary that it was "undesirable that any person of recent German nationality or association should at the present time be connected in an important capacity with any company or firm engaged in the production of munitions of war".[3] Booth showed this to Gruban and told him that the only way to save the company and prevent Gruban being interned was for him to transfer the ownership of the company to Booth.[4] Gruban did this, and Booth immediately "came out in his true colours",[4] treating Gruban with contempt and refusing to help support his wife and family now that Gruban had no income.[4] Eventually Booth wrote to the Ministry of Munitions saying that Gruban had "taken leave of his senses", and the Ministry had Gruban interned.[4]

Gruban appealed against the internment order, and was called before a court consisting of Mr Justice Younger and Mr Justice Sankey.[4] After reviewing the facts of the case and the stories of Gruban and Booth the judges ordered the immediate release of Gruban, and recommended that he seek legal advice to see if he could regain control of his company.[4] After he was released Gruban found a solicitor, W.J. Synott, who gave the case to Patrick Hastings.[5]

Trial

Hastings felt that their best chances lay in interviewing Christopher Addison about his contact with Booth; as Addison was a government minister he could be relied on to tell the truth.[5] The case of Gruban v Booth opened on 7 May 1917 at the King's Bench Division of the High Court of Justice in front of Mr Justice Coleridge.[5] Patrick Hastings and Hubert Wallington represented Gruban, while Booth was represented by Rigby Swift KC and Douglas Hogg.[5] The trial attracted such public interest that on the final day the barristers found it physically difficult to get through the crowds surrounding the Law Courts.[5]

As counsel for the prosecution, Hastings was the first barrister to speak. In his opening speech to the jury he criticised Booth for loving money rather than his country, saying that one of the things which the English prided themselves on was fair play, and "no matter how loudly the defendant raises the cry of patriotism, I feel sure that your sense of fair play, gentlemen, will ensure a verdict that the defendant is unfit to sit in the House of Commons, as he has been guilty of fraud".[6] Hastings then called Gruban to the witness stand, and asked him to tell the jury what had happened. Gruban described how Booth had claimed to have influence over David Lloyd George.[6] Booth was then cross-examined by Rigby Swift.[6]

Booth was then called to the witness stand, and initially claimed that Gruban had claimed to be "a very powerful man" and that it had been a case of Gruban using his power to help Booth, not the other way around.[6] He was still in the witness box when the court day ended, and the next morning it was announced that Christopher Addison had come to the court.[7] The judge allowed Addison to give his testimony before they continued with Booth, and during a cross-examination by Hastings Addison stated that he had not been advising Booth in any way, and that "to say that Gruban's only chance of escape from internment was to hand over his shares to Mr Booth was a lie".[7]

The final witness was Handel Booth himself.[8] Booth stated that he would never have asked for a ten-percent commission on the Birmingham contract, and that he had never claimed he could influence government ministers.[8] Hastings showed the jury that both of these statements were lies, first by showing the piece of paper Booth had scribbled the "Birmingham contract" memo on and then by showing a telegram from Booth to Gruban in which Booth claimed that he "[had] already spoken to a Cabinet Minister and high official".[8]

In his summing up Mr Justice Coleridge was "on the whole unfavourable to Booth". He also pointed out that the German nationality of Gruban might prejudice the jury, and asked them to "be sure that you permit no prejudice on their hand to disturb the balance of the scales of justice".[9] The jury decided the case in only ten minutes, finding Booth guilty and awarding Gruban £4,750.[9]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Hyde (1960) p.57

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Hyde (1960) p.58

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hyde (1960) p.59

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Hyde (1960) p.60

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Hyde (1960) p.61

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Hyde (1960) p.62

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hyde (1960) p.63

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Hyde (1960) p.64

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Hyde (1960) p.67

Bibliography

- Hyde, H Montgomery (1960). Sir Patrick Hastings, his life and cases. London: Heinemann. OCLC 498180.

Further reading

- Hastings, Patrick, Cases in Court, William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1949