Group velocity

The group velocity of a wave is the velocity with which the overall shape of the waves' amplitudes—known as the modulation or envelope of the wave—propagates through space.

For example, if a stone is thrown into the middle of a very still pond, a circular pattern of waves with a quiescent center appears in the water. The expanding ring of waves is the wave group, within which one can discern individual wavelets of differing wavelengths traveling at different speeds. The longer waves travel faster than the group as a whole, but their amplitudes diminish as they approach the leading edge. The shorter waves travel more slowly, and their amplitudes diminish as they emerge from the trailing boundary of the group.

Definition and interpretation

Definition

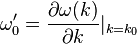

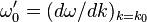

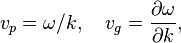

The group velocity vg is defined by the equation:[2][3][4][5]

where ω is the wave's angular frequency (usually expressed in radians per second), and k is the angular wavenumber (usually expressed in radians per meter).

The function ω(k), which gives ω as a function of k, is known as the dispersion relation.

- If ω is directly proportional to k, then the group velocity is exactly equal to the phase velocity. A wave of any shape will travel undistorted at this velocity.

- If ω is a linear function of k, but not directly proportional (ω=ak+b), then the group velocity and phase velocity are different. The envelope of a wave packet (see figure on right) will travel at the group velocity, while the individual peaks and troughs within the envelope will move at the phase velocity.

- If ω is not a linear function of k, the envelope of a wave packet will become distorted as it travels. This distortion is directly related to group velocity, as follows. Since a wave packet contains a range of different frequencies, the group velocity ∂ω/∂k is a range of different values (because ω is not a linear function of k). Therefore the envelope does not move at a single velocity, but a range of different velocities, so the envelope gets distorted. See further discussion below.

Derivation

One derivation of the formula for group velocity is as follows.[6][7]

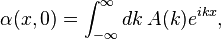

Consider a wave packet as a function of position x and time t: α(x,t). Let A(k) be its Fourier transform at time t=0:

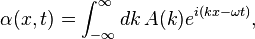

By the superposition principle, the wavepacket at any time t is:

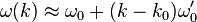

where ω is implicitly a function of k. We assume that the wave packet α is almost monochromatic, so that A(k) is sharply peaked around a central wavenumber k0. Then, linearization gives:

where  and

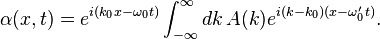

and  (see next section for discussion of this step). Then, after some algebra,

(see next section for discussion of this step). Then, after some algebra,

There are two factors in this expression. The first factor,  , describes a perfect monochromatic wave with wavevector

, describes a perfect monochromatic wave with wavevector  , with peaks and troughs moving at the phase velocity

, with peaks and troughs moving at the phase velocity  within the envelope of the wavepacket. The other factor,

within the envelope of the wavepacket. The other factor,  , gives the envelope of the wavepacket. This envelope function depends on position and time only through the combination

, gives the envelope of the wavepacket. This envelope function depends on position and time only through the combination  . Therefore, the envelope of the wavepacket travels at velocity

. Therefore, the envelope of the wavepacket travels at velocity  . This explains the group velocity formula.

. This explains the group velocity formula.

Higher-order terms in dispersion

Part of the previous derivation is the assumption:

If the wavepacket has a relatively large frequency spread, or if the dispersion  has sharp variations (such as due to a resonance), or if the packet travels over very long distances, this assumption is not valid. As a result, the envelope of the wave packet not only moves, but also distorts. Loosely speaking, different frequency-components of the wavepacket travel at different speeds, with the faster components moving towards the front of the wavepacket and the slower moving towards the back. Eventually, the wave packet gets stretched out.

has sharp variations (such as due to a resonance), or if the packet travels over very long distances, this assumption is not valid. As a result, the envelope of the wave packet not only moves, but also distorts. Loosely speaking, different frequency-components of the wavepacket travel at different speeds, with the faster components moving towards the front of the wavepacket and the slower moving towards the back. Eventually, the wave packet gets stretched out.

The next-higher term in the Taylor series (related to the second derivative of  ) is called group velocity dispersion. This is an important effect in the propagation of signals through optical fibers and in the design of high-power, short-pulse lasers.

) is called group velocity dispersion. This is an important effect in the propagation of signals through optical fibers and in the design of high-power, short-pulse lasers.

Physical interpretation

The group velocity is often thought of as the velocity at which energy or information is conveyed along a wave. In most cases this is accurate, and the group velocity can be thought of as the signal velocity of the waveform. However, if the wave is travelling through an absorptive medium, this does not always hold. Since the 1980s, various experiments have verified that it is possible for the group velocity of laser light pulses sent through specially prepared materials to significantly exceed the speed of light in vacuum. However, superluminal communication is not possible in this case, since the signal velocity remains less than the speed of light. It is also possible to reduce the group velocity to zero, stopping the pulse, or have negative group velocity, making the pulse appear to propagate backwards.[1] However, in all these cases, photons continue to propagate at the expected speed of light in the medium.[8][9][10][11]

Anomalous dispersion happens in areas of rapid spectral variation with respect to the refractive index. Therefore, negative values of the group velocity will occur in these areas. Anomalous dispersion plays a fundamental role in achieving backward propagating and superluminal light. Anomalous dispersion can also be used to produce group and phase velocities that are in different directions.[9] Materials that exhibit large anomalous dispersion allow the group velocity of the light to exceed c and/or become negative.[11][12]

History

The idea of a group velocity distinct from a wave's phase velocity was first proposed by W.R. Hamilton in 1839, and the first full treatment was by Rayleigh in his "Theory of Sound" in 1877.[13]

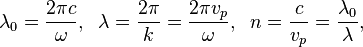

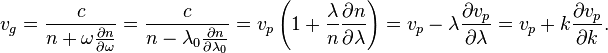

Other expressions

For light, the refractive index n, vacuum wavelength λ0, and wavelength in the medium λ, are related by

with vp = ω/k the phase velocity.

The group velocity, therefore, can be calculated by any of the following formulas:

In three dimensions

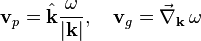

For waves traveling through three dimensions, such as light waves, sound waves, and matter waves, the formulas for phase and group velocity are generalized in a straightforward way:[14]

- One dimension:

- Three dimensions:

where  means the gradient of the angular frequency

means the gradient of the angular frequency  as a function of the wave vector

as a function of the wave vector  , and

, and  is the unit vector in direction k.

is the unit vector in direction k.

If the waves are propagating through an anisotropic (i.e., not rotationally symmetric) medium, for example a crystal, then the phase velocity vector and group velocity vector may point in different directions.

See also

- Wave propagation

- Dispersion (optics) for a full discussion of wave velocities

- Phase velocity

- Front velocity

- Group delay -- "The group velocity of light in a medium is the inverse of the group delay per unit length."[15]

- Phase delay

- Signal velocity

- Slow light

- Wave propagation speed

- Defining equation (physics)

- Matter wave#Group velocity

- Soliton

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Nemirovsky, Jonathan; Rechtsman, Mikael C and Segev, Mordechai (9 April 2012). "Negative radiation pressure and negative effective refractive index via dielectric birefringence" (PDF). Optics Express 20 (8): 8907–8914. Bibcode:2012OExpr..20.8907N. doi:10.1364/OE.20.008907. PMID 22513601.

- ↑ Brillouin, Léon (2003) [1946], Wave Propagation in Periodic Structures: Electric Filters and Crystal Lattices, Dover, p. 75, ISBN 978-0-486-49556-9

- ↑ Lighthill, James (2001) [1978], Waves in fluids, Cambridge University Press, p. 242, ISBN 978-0-521-01045-0

- ↑ Lighthill (1965)

- ↑ Hayes (1973)

- ↑ Griffiths, David J. (1995). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. Prentice Hall. p. 48.

- ↑ David K. Ferry (2001). Quantum Mechanics: An Introduction for Device Physicists and Electrical Engineers (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-7503-0725-3.

- ↑ Gehring, George M.; Schweinsberg, Aaron; Barsi, Christopher; Kostinski, Natalie; Boyd, Robert W. (2006), "Observation of a Backward Pulse Propagation Through a Medium with a Negative Group Velocity", Science 312 (5775): 895–897, Bibcode:2006Sci...312..895G, doi:10.1126/science.1124524, PMID 16690861

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Dolling, Gunnar; Enkrich, Christian; Wegener, Martin; Soukoulis, Costas M.; Linden, Stefan (2006), "Simultaneous Negative Phase and Group Velocity of Light in a Metamaterial", Science 312 (5775): 892–894, Bibcode:2006Sci...312..892D, doi:10.1126/science.1126021, PMID 16690860

- ↑ Schweinsberg, A.; Lepeshkin, N. N.; Bigelow, M.S.; Boyd, R. W.; Jarabo, S. (2005), "Observation of superluminal and slow light propagation in erbium-doped optical fiber", Europhysics Letters 73 (2): 218–224, Bibcode:2006EL.....73..218S, doi:10.1209/epl/i2005-10371-0

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Bigelow, Matthew S.; Lepeshkin, Nick N.; Shin, Heedeuk; Boyd, Robert W. (2006), "Propagation of a smooth and discontinuous pulses through materials with very large or very small group velocities", Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 18 (11): 3117–3126, Bibcode:2006JPCM...18.3117B, doi:10.1088/0953-8984/18/11/017

- ↑ Withayachumnankul, W.; Fischer, B. M.; Ferguson, B.; Davis, B. R.; Abbott, D. (2010), "A Systemized View of Superluminal Wave Propagation", Proceedings of the IEEE 98 (10): 1775–1786, doi:10.1109/JPROC.2010.2052910

- ↑ Brillouin, Léon (1960), Wave Propagation and Group Velocity, New York: Academic Press Inc., OCLC 537250

- ↑ Atmospheric and oceanic fluid dynamics: fundamentals and large-scale circulation, by Geoffrey K. Vallis, p239

- ↑ http://www.rp-photonics.com/group_delay.html

Further reading

- Tipler, Paul A.; Llewellyn, Ralph A. (2003), Modern Physics (4th ed.), New York: W. H. Freeman and Company, p. 223, ISBN 0-7167-4345-0.

- Biot, M. A. (1957), "General theorems on the equivalence of group velocity and energy transport", Physical Review 105 (4): 1129–1137, Bibcode:1957PhRv..105.1129B, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.105.1129

- Whitham, G. B. (1961), "Group velocity and energy propagation for three-dimensional waves", Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 14 (3): 675–691, doi:10.1002/cpa.3160140337

- Lighthill, M. J. (1965), "Group velocity", IMA Journal of Applied Mathematics 1 (1): 1–28, doi:10.1093/imamat/1.1.1

- Bretherton, F. P.; Garrett, C. J. R. (1968), "Wavetrains in inhomogeneous moving media", Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 302 (1471): 529–554, Bibcode:1968RSPSA.302..529B, doi:10.1098/rspa.1968.0034

- Hayes, W. D. (1973), "Group velocity and nonlinear dispersive wave propagation", Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 332 (1589): 199–221, Bibcode:1973RSPSA.332..199H, doi:10.1098/rspa.1973.0021

- Whitham, G. B. (1974), Linear and nonlinear waves, Wiley, ISBN 0471940909

External links

- Greg Egan has an excellent Java applet on his web site that illustrates the apparent difference in group velocity from phase velocity.

- Group and Phase Velocity - Java applet with configurable group velocity and frequency.

- Maarten Ambaum has a webpage with movie demonstrating the importance of group velocity to downstream development of weather systems.

- Phase vs. Group Velocity – Various Phase- and Group-velocity relations (animation)

| Velocities of waves |

|---|

| Phase velocity • Group velocity • Front velocity • Signal velocity |