Group testing

In combinatorial mathematics, group testing refers to any procedure which breaks up the task of locating elements of a set which have certain properties into tests on subsets ("groups") rather than on individual elements. A familiar example of this type of technique is the false coin problem of recreational mathematics. In this problem there are n coins and one of them is false, weighing less than a real coin. The objective is to find the false coin, using a balance scale, in the fewest number of weighings. By repeatedly dividing the coins in half and comparing the two halves, the false coin can be found quickly as it is always in the lighter half.[1]

Schemes for carrying out such group testing can be simple or complex and the tests involved at each stage may be different. Schemes in which the tests for the next stage depend on the results of the previous stages are called adaptive procedures, while schemes designed so that all the tests are known beforehand are called non-adaptive procedures. The structure of the scheme of the tests involved in a non-adaptive procedure is known as a pooling design.

Background

Robert Dorfman's paper in 1943 introduced the field of (Combinatorial) Group Testing. The motivation arose during the Second World War when the United States Public Health Service and the Selective service embarked upon a large scale project. The objective was to weed out all syphilitic men called up for induction. However, syphilis testing back then was expensive and testing every soldier individually would have been very cost heavy and inefficient. A basic breakdown of a test is:

- Draw sample from a given individual

- Perform required tests

- Determine presence or absence of syphilis

Say we have  soldiers, then this method of testing leads to

soldiers, then this method of testing leads to  tests. If we have 70-75% of the people infected then the method of individual testing would be reasonable. Our goal however, is to achieve effective testing in the more likely scenario where it does not make sense to test 100,000 people to get (say) 10 positives.

tests. If we have 70-75% of the people infected then the method of individual testing would be reasonable. Our goal however, is to achieve effective testing in the more likely scenario where it does not make sense to test 100,000 people to get (say) 10 positives.

The feasibility of a more effective testing scheme hinges on the following property. We can combine blood samples and test a combined sample together to check if at least one soldier has syphilis.

Modern interest in these testing schemes has been rekindled by the Human Genome Project.[2]

Formalization of the problem

We now formalize the group testing problem abstractly.

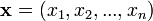

The total number of soldiers

The total number of soldiers  , an upper bound on the number of infected soldiers

, an upper bound on the number of infected soldiers  . The (unknown) information about which soldier is infected described as a vector

. The (unknown) information about which soldier is infected described as a vector  where

where  if the item

if the item  is infected else

is infected else  .

.

The Hamming Weight of  is defined as the number of

is defined as the number of  in

in  . Hence,

. Hence,  where

where  is the Hamming weight. The vector

is the Hamming weight. The vector  is an implicit input since we do not know the positions of

is an implicit input since we do not know the positions of  in the input. The only way to find out is to run the tests.

in the input. The only way to find out is to run the tests.

Formal notion of a Test

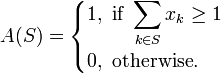

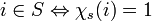

A query/test  is a subset of

is a subset of ![[n]](../I/m/de504dafb2a07922de5e25813d0aaafd.png) . The answer to the query

. The answer to the query ![S \subseteq [n]](../I/m/f90514b607e964d78f16ec0a6e8c680f.png) is defined as follows:

is defined as follows:

Note that the addition operation used by the summation is the logical- , i.e.

, i.e.

.

.

Goal

Compute  and minimize the number of tests required to determine

and minimize the number of tests required to determine

The question boils down to one of Combinatorial Searching. Combinatorial searching in general can be explained as follows: Say you have a set of  variables and each of these can take on

variables and each of these can take on  possible values. So, finding possible solutions that match a certain constraint is a problem of combinatorial searching. The major problem with such questions is that the solution can grow exponentially in the size of the input. Here, we have no direct questions or answers. Any piece of information can only be obtained using an indirect query.

possible values. So, finding possible solutions that match a certain constraint is a problem of combinatorial searching. The major problem with such questions is that the solution can grow exponentially in the size of the input. Here, we have no direct questions or answers. Any piece of information can only be obtained using an indirect query.

Definition

Given a set of

Given a set of  items with

items with  defects, the minimum number of tests that one would have to make to detect all the defective items is defined as

defects, the minimum number of tests that one would have to make to detect all the defective items is defined as  .

.

Consider the case when only one person in the group will test positive. Then if we tested in the naive way, in the best case we would at least have to test the first person to find out if he/she is infected. However, in the worst case one might have to end up testing the entire group and only the last person we test will turn out to really be the one who was infected. Hence,

Testing Methods

There are two basic principles via which the testing may be carried out:

- Adaptive Group Testing is where we test a given subset of items and, we get the answer from the test. We then base the next test on the outcome of the current test.

- Non-adaptive Group Testing on the other hand is when all the tests to be performed are decided a priori.[3]

Definition

Given a set of

Given a set of  items with

items with  defects,

defects,  is defined as the number of adaptive tests that one would have to make to detect all the defective items.

is defined as the number of adaptive tests that one would have to make to detect all the defective items.

One should note that in the case of group testing for the Syphilis problem, non-adaptive group testing is crucial. This is because the soldiers might be spread out geographically and adaptive group testing will need a lot of co-ordination.

Mathematical representation of the set of non-adaptive tests

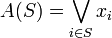

For, ![S \subseteq [n]](../I/m/f90514b607e964d78f16ec0a6e8c680f.png) , define

, define  such that

such that  .

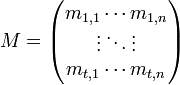

.  is a

is a  matrix of

matrix of  .

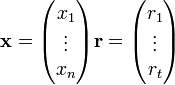

.  is the input vector transposed and

is the input vector transposed and  is the resultant. The construction is based on the grounds that for non-adaptive testing with

is the resultant. The construction is based on the grounds that for non-adaptive testing with  tests is represented by a

tests is represented by a  subset

subset ![S_i \subseteq [n] (1 \leq i \leq t)](../I/m/405c215a40b65d05e8f1adf879cc64d5.png) .

.  for a given

for a given  is the

is the  test.

test.  test matrix where

test matrix where  is one if for the

is one if for the  test,

test,  . Note that here multiplication is logical AND (

. Note that here multiplication is logical AND ( ) and addition is logical OR (

) and addition is logical OR ( ). Then,

). Then,  where

where  is the resultant of the matrix multiplication. To think of this in terms of testing, it is helpful to visualize matrix multiplication. Here,

is the resultant of the matrix multiplication. To think of this in terms of testing, it is helpful to visualize matrix multiplication. Here,  will have a 1 in position

will have a 1 in position  if and only if there was a

if and only if there was a  in that position in both

in that position in both  and

and  i.e. if that person was tested with that particular group and if he tested out to be positive.

i.e. if that person was tested with that particular group and if he tested out to be positive.

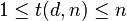

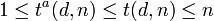

Bounds for testing on  and

and

The reason for  is due to the fact that any non-adaptive test can be performed by an adaptive test by running all of the tests in the first step of the adaptive test. Adaptive tests can be more efficient than non-adaptive tests since the test can be changed after certain things are discovered.

is due to the fact that any non-adaptive test can be performed by an adaptive test by running all of the tests in the first step of the adaptive test. Adaptive tests can be more efficient than non-adaptive tests since the test can be changed after certain things are discovered.

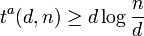

Lower bound on

Fix a valid group testing scheme with  tests. Now, for two distinct vectors

tests. Now, for two distinct vectors  and

and  where

where  , the resulting vectors will not be the same i.e.

, the resulting vectors will not be the same i.e.  . Here

. Here  is the resultant vector when

is the resultant vector when  . This is because, two valid inputs will never give us the same result. If this ever happened, then we would always have an error in finding both

. This is because, two valid inputs will never give us the same result. If this ever happened, then we would always have an error in finding both  and

and  . This gives us that the total number of distinct results is the volume of a Hamming Ball of radius

. This gives us that the total number of distinct results is the volume of a Hamming Ball of radius  , centered about

, centered about  i.e.

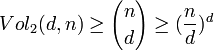

i.e.  . However, for

. However, for  bits, the total number of possible distinct vectors is

bits, the total number of possible distinct vectors is  . Hence,

. Hence,  . Taking the

. Taking the  on both sides gives us

on both sides gives us  .

.

Now,  . Therefore, we will end up having to perform a minimum of

. Therefore, we will end up having to perform a minimum of  tests.

tests.

Thus we have proved,

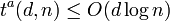

Upper bound on

.

.

Since we know that the upper bound on the number of positives is  , we run a binary search at most

, we run a binary search at most  times or until there are no more values to be found. To simplify the problem we try to give a testing sccheme that uses

times or until there are no more values to be found. To simplify the problem we try to give a testing sccheme that uses  adaptive tests to figure out a

adaptive tests to figure out a  such that

such that  . The related problem is solved by splitting

. The related problem is solved by splitting ![[n]](../I/m/de504dafb2a07922de5e25813d0aaafd.png) in two halves and querying to find a

in two halves and querying to find a  in one of those and then proceeding recursively to find the exact position in the half where the query returned a

in one of those and then proceeding recursively to find the exact position in the half where the query returned a  . This will take

. This will take  time or if the first query is performed on the whole set, it will take

time or if the first query is performed on the whole set, it will take  . Once a

. Once a  is found, the search is then repeated after removing the

is found, the search is then repeated after removing the  co-ordinate. This can be done at most

co-ordinate. This can be done at most  times. This justifies the running time of

times. This justifies the running time of  .

For a full proof and an algorithm for the problem refer to: CSE545 at the University at Buffalo

.

For a full proof and an algorithm for the problem refer to: CSE545 at the University at Buffalo

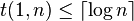

Upper bound on

This upper bound is for the special case where

This upper bound is for the special case where  i.e. there is a maximum of 1 positive. In this case, the matrix multiplication gets simplified and the resultant

i.e. there is a maximum of 1 positive. In this case, the matrix multiplication gets simplified and the resultant  represents the binary representation of

represents the binary representation of  for test

for test  . This gives a lower bound of

. This gives a lower bound of  . Note that decoding becomes trivial because the binary representation of

. Note that decoding becomes trivial because the binary representation of  gives us the location directly. The group test matrix here is just the parity check matrix

gives us the location directly. The group test matrix here is just the parity check matrix  for the

for the ![[2^m - 1, 2^m-m-1, 3]](../I/m/1a5ca3f7979dea6f5f94200a5c4ec924.png) Hamming code.

Hamming code.

Thus as the upper and lower bounds are the same, we have a tight bound for  when

when  . Such tight bounds are not known for general

. Such tight bounds are not known for general  .

.

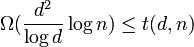

Upper Bounds for Non-Adaptive Group Testing

For non-adaptive group testing upper bounds we shift focus toward disjunct matrices. Disjunct matrices have been used for many of the bounds because of their nice properties. Through use of different constructions of disjunct matrices it has been shown that  . Also for upper bounds we currently have that (i)

. Also for upper bounds we currently have that (i)  (explicit construction) and (ii)

(explicit construction) and (ii)  (strongly explicit construction). It is good to note that the current known lower bound for

(strongly explicit construction). It is good to note that the current known lower bound for  is already a

is already a  factor larger than the upper bound for

factor larger than the upper bound for  . Another thing to note is that give the smallest upper bound and biggest lower bound they are only off by a factor of

. Another thing to note is that give the smallest upper bound and biggest lower bound they are only off by a factor of  which is fairly small.

which is fairly small.

See also

- Disjunct Matrix

- Robert Dorfman

- Concatenated error correction codes

- Hamming weight

- Hamming code

Notes

- ↑ A bit more precisely – if there are an odd number of coins to be weighed, pick one to put aside and divide the rest into two equal piles. If the two piles have equal weight, the bad coin is the one put aside, otherwise the one put aside was good and no longer has to be tested.

- ↑ Colbourn & Dinitz 2007, pg. 574, Section 46: Pooling Designs

- ↑ Colbourn & Dinitz 2007, pg. 631, Section 56.4

References

- Atri Rudra's course on Error Correcting Codes: Combinatorics, Algorithms, and Applications (Spring 2007), Lectures 7.

- Atri Rudra's course on Error Correcting Codes: Combinatorics, Algorithms, and Applications (Spring 2010), Lectures 10, 11, 28, 29

- Colbourn, Charles J.; Dinitz, Jeffrey H. (2007), Handbook of Combinatorial Designs (2nd Edition ed.), Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/ CRC, ISBN 1-58488-506-8

- Dorfman, R. The Detection of Defective Members of Large Populations. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 14(4), 436-440. Retrieved from

- Du, D., & Hwang, F. (2006). Pooling Designs and Nonadaptive Group Testing. Boston: Twayne Publishers.

- Ely Porat, Amir Rothschild: Explicit Non-adaptive Combinatorial Group Testing Schemes. ICALP (1) 2008: 748-759