Greco-Italian War

| Greco-Italian War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Balkans Campaign of World War II | |||||||

Greek newspaper announcing the war | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

565,000 men[1] (about 87,000 men at the beginning of the attack[2]) 463 aircraft[3] 163 light tanks |

Less than 300,000 men 77 aircraft[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

13,755[4][5][6] dead |

13,325 dead | ||||||

The Greco-Italian War, also known as the Italo-Greek War, was a conflict between Italy and Greece, which lasted from 28 October 1940 to 23 April 1941. The conflict marked the beginning of the Balkans campaign of World War II and the initial Greek counteroffensive, the first successful land campaign against the Axis powers in the war.[8] The conflict known as the Battle of Greece began with the intervention of Nazi Germany on 6 April 1941. In Greece, it is known as the "War of '40"[9] and in Italy as the "War of Greece".[10]

By the middle of 1940, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini wanted to emulate Adolf Hitler's conquests to prove to his Axis partner that he could lead Italy to similar military successes.[2][11][12] Italy had occupied Albania in the spring of 1939 and several British strongholds in Africa, such as the Italian conquest of British Somaliland in the summer of 1940, but could not claim victories on the same scale as Nazi Germany. At the same time, Mussolini wanted to reassert Italy's interests in the Balkans, feeling threatened by Germany, and secure bases from which British outposts in the eastern Mediterranean could be attacked. He was irritated that Romania, a Balkan state in the supposed Italian sphere of influence, had accepted German protection for its Ploiești oil fields in mid-October.

On 28 October 1940, after Greek prime minister Ioannis Metaxas rejected an Italian ultimatum demanding the occupation of Greek territory, Italian forces invaded Greece. The Greek army counterattacked and forced the Italians to retreat. By mid-December, the Greeks occupied nearly a quarter of Albania, tying down 530,000 Italian troops. In March 1941, a major Italian counterattack failed.[13] On 6 April 1941, coming to the aid of Italy,[14][15][16][17] Nazi Germany invaded Greece through Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. On 12 April, the Greek army began retreating from Albania to avoid being cut off by the rapid German advance. On 20 April, the Greek army of Epirus surrendered to the Germans and on 23 April 1941, the armistice was repeated, including the Italians, effectively ending the Greco-Italian war. By the end of April, 1941, Greece was occupied by Italian, German and Bulgarian forces, with Italy occupying nearly two thirds of the country.

The Greek victory over the initial Italian offensive of October 1940 was the first major Allied land victory of the Second World War and helped raise morale in occupied Europe. Some historians, such as John Keegan, argue that it may have influenced the course of the entire war by forcing Germany to postpone the invasion of the Soviet Union in order to assist Italy against Greece. The delay meant that the German forces invading the Soviet Union had not attained their objectives for that year before the harsh Russian winter, leading to their defeat at the Battle of Moscow. Hillgruber, Kershaw and Rintelen disagree with Keegan, maintaining that it was an unusually wet May, inadequate logistics and a gross underestimation of Russian reserves of manpower, which led to the ultimate failure of Operation Barbarossa.[18][19][20]

Background

Greco-Italian relations in the early 20th century

Ever since Italian unification, Italy had aspired to Great Power status and Mediterranean hegemony. Under the Fascist regime, the establishment of a new Roman Empire, including Greece, was often proclaimed by Mussolini.

In the 1910s, Italian and Greek interests were already clashing over Albania and the Dodecanese. Albania, Greece's northwestern neighbour, was, from its establishment, effectively an Italian protectorate. Both Albania and Greece claimed Northern Epirus, inhabited by a large[21] Greek population. Furthermore, Italy had occupied the predominantly Greek-inhabited Dodecanese Islands in the southeastern Aegean since the Italo-Turkish War of 1912. Although Italy promised their return in the 1919 Venizelos–Tittoni accords, it later reneged on the agreement.[22] Clashes between the two countries' forces occurred during the occupation of Anatolia. The goal remained without practical consequences of note during the years when Fascism was consolidating its hold on the Italian state, and on society. In its aftermath, the new Fascist government, headed by Mussolini, used the murder of an Italian general at the Greco-Albanian border to bombard and occupy Corfu, the most important of the Ionian Islands. These islands, which had been under Venetian rule until the late 18th century, were a target of Italian expansionism. A period of normalization followed, especially the signing of a friendship agreement between the two countries on 23 September 1928, and under the premiership of Eleftherios Venizelos in Greece from 1928 to 1932. Fascist Italy was not prepared for foreign wars beyond low intensity conflicts. The state was obstructed with debts as a legacy of the Italy in the First World War. Most regions, in the south, were sub-developed, while the national income was less than a quarter of that of the United Kingdom.[23]

In 1936, the 4th of August Regime came to power under the leadership of Ioannis Metaxas. Plans were laid down for the reorganization of the country's armed forces, including a fortified defensive line along the Greco-Bulgarian frontier, which would be named the "Metaxas Line". In the following years, great investments were made to modernize the army. It was technologically upgraded, largely re-equipped, and, as a whole, dramatically improved from its previous state. Additionally, the Greek government purchased new arms for its three armies. However, due to increasing threats and the eventual outbreak of war, the most significant purchases from abroad, made from 1938 to 1939, were never or only partially delivered. A massive contingency plan was developed, and great amounts of food and utilities were stockpiled in many parts of the country for use in the event of war.

Mussolini held his plan in standby. He was aiming for war, not peace. In a far-reaching speech, an updated version of the long-held vision, of the Fascist Grand Council on 4 February 1939, he envisaged a war with the Allies to attain the Italian version of German's Lebensraum. Italy was effectively landlocked by British domination of the Mediterranean, blocking access to oceans and prosperity through the control of the Strait of Gibraltar in the west and the Suez Canal in the east. Encircled by hostile countries and deprived of any scope for expansion, Italy was "a prisoner of the Mediterranean". The task of Italian policy was to "break the bars of the prison" and "march to the ocean". But whether this march was to the Indian, or the Atlantic, ocean, "we will find ourselves confronted with Anglo-French opposition".[24]

The German occupation on 15 March of what was left of Czechoslovakia, without prior notice to his Axis partner, showed where the power was. The Munich settlement, brokered by Mussolini, was ripped up by Hitler. When Hitler’s emissary presented a verbal message of explanation and gratitude to Mussolini, a despondent Mussolini wished to withhold the news from the press. "The Italians would laugh at me", he lamented. "Every time Hitler occupies a country he sends me a message".[25] On 7 April 1939, Italian troops occupied Albania, gaining an immediate land border with Greece. This action led to a British and French guarantee for the territorial integrity of Greece. Mussolini wished to take Italy in war right from the start, but he had been forced to bow to pressure from within the Fascist regime, at least for the time being, and wait to see how events would unfold. For the time being, Mussolini felt deterred from taking the country to war, and compelled to accept the new status, unknown in the international law, of non-belligerent; less demanding than neutrality, but falling short of what he demanded from Fascist martial values.[26]

Diplomatic and military developments in 1939–1940

Ever since the Italian takeover in Albania in April 1939, Greco-Italian relations had been deteriorating. For the Greeks, however, this development canceled all previous plans, and hasty preparations were made to defend against an Italian attack. From the time before the German invasion of Poland, relations between Greece and Italy became tense. By 11 September 1939, Mussolini told his representative in Athens, Emanuele Grazzi, that "Greece does not lie on our path, and we want nothing from her". Nine days later he was equally plain in speaking to General Alfredo Guzzoni, the military commander in Albania, derided by Ciano for being "small, with such a big belly, and dyed hair". Mussolini informed him that "war with Greece is off. Greece is a bare bone, and is not worth the loss of a single Sardinian grenadier". Italian troops were pulled back to about twelve miles from the Greek border. The general staff’s invasion study was consigned to the bottom drawer.[27]

Italy, in the last days of May, took the road to war against the Allies. Badoglio, according to his postwar account, went on to recall that he and Balbo were dumbfounded at the news, and Mussolini taken aback at the reception. Badoglio pointed out in terms that Italy was unprepared for war. "It is suicide", he later claimed he remarked.[28] A quite different scenario was painted by Churchill. "It was certainly only common prudence for Mussolini to see how the war would go before committing himself and his country irrevocably", Churchill wrote:

The process of waiting was by no means unprofitable. Italy was courted by both sides, and gained much consideration for her interests, many profitable contracts, and time to improve her armaments. Thus the twilight months had passed. It is an interesting speculation what the Italian fortunes would have been if this policy had been maintained … Peace, prosperity, and growing power would have been the prize of a persistent neutrality. Once Hitler was embroiled with Russia this happy state might have been almost indefinitely prolonged, with ever-growing benefits, and Mussolini might have stood forth in the peace or in the closing year of the war as the wisest statesman the sunny peninsula and its industrious and prolific people had known. This was a more agreeable situation than that which in fact awaited him.[29]

Italy's "parallel war"

All was quiet until Italy joined the war in June of 1940. Soon after the fall of France, Mussolini set his sights on Greece. As war exploded in Europe, Metaxas tried to keep Greece out of the conflict, but, as it progressed, he felt increasingly closer to the United Kingdom, encouraged by the ardent Anglophile, King George II, who provided the main support for the regime. Metaxas, who had always been an admirer of Italy, had built strong economic ties with Hitler's Germany.[2] According to a 3 July 1940 entry in the diary of his son-in-law and foreign minister, Count Galeazzo Ciano:

...British ships, perhaps even aircraft, are sheltered and refueled in Greece. Mussolini is enraged. He has decided to act.

In June 1940, Jacomoni schooled Ciano with the history of the headless body of Daut Hoxha, an Albanian Cham patriot, which was discovered near the village of Vrina.[30] Jacomoni blamed his murder on Greek secret agents and, as the possibility of an Italian attack on Greece drew nearer, he began arming Albanian irregular bands to be used against Greece.[31] On 11 August, the day after Ciano had set Mussolini on the path to conflict with Greece, the Italians, especially the Governor of Albania, Francesco Jacomoni, began using the issue of the Cham Albanian minority in Greek Epirus as a means to rally Albanian support. Although Albanian enthusiasm for the "liberation of Chameria" was muted, Jacomoni sent repeated overoptimistic reports to Rome on Albanian support.[31] Ciano reported that Mussolini

continues to talk about a lightning attack into Greece at about the end of September.[32]

A propaganda campaign against Greece was launched in Italy and repeated acts of provocation were carried out, such as overflights of Greek territory and attacks by aircraft on Greek naval vessels. These reached their peak with the torpedoing and sinking of the Greek light cruiser Elli by the submarine Delfino in Tinos harbor on 15 August 1940, a national religious holiday. Despite evidence of Italian responsibility, the Greek government announced that the attack had been carried out by a submarine of unknown nationality.[2] Although the facade of neutrality was preserved, the people were well aware of the real perpetrators, accusing Mussolini and his foreign minister, Count Ciano.[33] In the meantime, the original Italian plan of attacking Yugoslavia was shelved due to German opposition and lack of the necessary transport.[34]

Hitler's decision to invade Poland without informing his Axis partner, as well as his interference in Romania and Croatia, were among Mussolini's considerations in making the decision to attack Greece as a preemptive measure against what he considered to be "a predatory German ally".[35] On 7 October 1940, the Germans entered Romania in order to assume control of the Ploesti oil fields.[36] Mussolini, who was not informed in advance, was infuriated by this action, regarding it as a German encroachment on southeastern Europe, an area Italy claimed as in its exclusive sphere of influence.[35] Mussolini was also furious that the Nazi foreign ministry had attempted to prevent the Italian press corps from reporting that the German army had reached Bucharest. The Italian dictator became even more upset when he learned that the Romanians would probably not allow the Italian army into their country without German consent. He took the news as a personal affront and as an insult against his country and became eager to respond to this perceived loss of prestige through occupying Greece without informing the Germans ahead of time. Mussolini revealed in a private comment to his son-in-law, Count Ciano:

Hitler always faces me with a fait accompli. This time I am going to pay him back in his own coin. He will find out from the newspapers that I have occupied Greece.[37]

Aside from his personal anger when faced with the German fait accomplis, Mussolini was also driven by political considerations. Given that Italy's share of military successes was far smaller than that of Germany at the time, he worried about his image amongst the Italian public, which would be unsettled by further indications of German military superiority and Italy's inferior position in the Axis alliance. He thus wanted to attack and occupy Greece to increase his prestige and restore balance in the alliance by providing Italy with its first significant share of the spoils of war.

Mussolini made the impulsive decision to invade Greece, an act which was typical of Mussolini's leadership style. His fury over the stationing of German troops in Romania, however, affected only the timing of the attack, since an attack on Greece was already part of Mussolini's long-term plans of establishing Italian rule over the Balkans and the Mediterranean. Although Hitler had conceded that Greece would be left to Italy's sphere of influence, repeated warnings had been given that turmoil in the Balkans was to be avoided. Mussolini was wishful thinking that at the Brenner meeting Hitler had given the Italian military carte blanche in Greece.[38] On 13 October, he ordered that the invasion should be launched on 26 October.[39] The following day, Mussolini summoned a meeting of his military chiefs to take place next day. Only the chief of the general staff, Marshal Pietro Badoglio, voiced objections, citing the need to assemble a force of at least 20 divisions prior to invasion. However, the local commander in Albania, Lt. Gen. Sebastiano Visconti Prasca, argued that only three further divisions would be needed, and these only after the first phase of the offensive, capturing Epirus, had been completed. Mussolini was reassured by his staff that the war in Greece would be a campaign of ten to fifteen days.[40]

This overconfidence explains why Mussolini felt he could let 300,000 troops and 600,000 reservists go home for the harvest just before the invasion.[2][41] There were supposed to be 1,750 lorries used in the invasion, but only 107 turned up. The number of divisions was inflated because Mussolini had switched from three-regiment to two-regiment divisions. Lieutenant General Prasca knew he would lose his command if more than five divisions were sent, so he convinced Mussolini that five were all he needed.[42] Foreign Minister Ciano, who said that he could rely on the support of several easily corruptible Greek personalities, was assigned to find a casus belli.[43] The following week, Tsar Boris III of Bulgaria was invited to take part in the coming action against Greece, but he refused Mussolini's invitation.[2] The possibility that Greek personalities, as well as Greek officials situated in the front area, could be corrupted or not react to an invasion, proved to be mostly internal propaganda used by Italians generals and personalities in favor of a military intervention;[2] the same was true for an alleged revolt of the Albanian minority living in Chameria, located in the Greek territory immediately behind the boundary, which would break out after the beginning of the attack.[2]

Italian ultimatum and Greek reaction

| "I said that we would break the Negus' back. Now, with the same, absolute certainty, I repeat, absolute, I tell you that we will break Greece's back." |

| Mussolini's speech in Palazzo Venezia, 18 November 1940[44][45] |

On the eve of 28 October 1940, Italy's ambassador in Athens, Emanuele Grazzi, handed an ultimatum from Mussolini to Metaxas. It demanded free passage for his troops to occupy unspecified strategic points inside Greek territory. Greece had been friendly towards Nazi Germany, profiting from mutual trade relations, but now Germany's ally, Italy, intended to invade Greece. Metaxas rejected the ultimatum with the words "Alors, c'est la guerre" (French for "then it is war."). In this, he echoed the will of the Greek people to resist, a will that was popularly expressed in one word: "ochi" (Όχι) (Greek for "no"). Within hours, Italy began attacking Greece from Albania. The outbreak of hostilities was first announced by Athens Radio early in the morning of 28 October, with the two-sentence dispatch of the general staff: "Since 05:30 this morning, the enemy is attacking our vanguard on the Greek-Albanian border. Our forces are defending the fatherland."

Shortly thereafter, Metaxas addressed the Greek people with these words: "The time has come for Greece to fight for her independence. Greeks, now we must prove ourselves worthy of our forefathers and the freedom they bestowed upon us. Greeks, now fight for your fatherland, for your wives, for your children and the sacred traditions. The struggle now is for everything."[46] The last sentence was a verbatim quote from The Persians, by the dramatist Aeschylus. In response to this address, the people of Greece reportedly spontaneously went out to the streets singing Greek patriotic songs and shouting anti-Italian slogans. Hundreds of thousands of volunteers, men and women, in all parts of Greece, headed to army recruitment offices to enlist.[47] Despite the opinion of several Italian generals and politicians pushing for war, according to which the Greek government was not loved by the people, the whole Greek nation proved to be united in the face of aggression.[2] Even the imprisoned leader of Greece's banned Communist Party, Nikolaos Zachariadis, issued an open letter advocating resistance, despite the still existing Nazi–Soviet pact, thereby contravening the current Comintern line. However, in later letters, he accused Metaxas of waging an imperialistic war and called upon Greek soldiers to desert their ranks and overthrow the regime.

Mussolini's war aims

The initial goal of the campaign for the Italians was to establish a Greek puppet state under Italian influence.[48] This new Greek state would permit the Italian annexation of the Ionian Islands, and the Aegean island groups of the Sporades and the Cyclades, to be administered as a part of the Italian Aegean Islands.[49] These islands were claimed on the basis that they had once belonged to the Venetian Republic and the Venetian client state of Naxos.[50] In addition, the Epirus and Acarnania regions were to be separated from the rest of the Hellenic territory and the Italian-controlled Kingdom of Albania was to annex territory between the Hellenic northwestern frontier and the Florina–Pindus–Arta–Preveza line.[49] The Italians further projected to partly compensate the Greek state for its extensive territorial losses by allowing it to annex the British Crown Colony of Cyprus after the war had reached a victorious conclusion.[51]

Order of battle and opposing plans

The front, roughly 150 km (93.2 mi) in breadth, featured extremely mountainous terrain with very few roads. The Pindus mountain range divided it into two distinct theatres of operations: Epirus and Western Macedonia.

The order to invade Greece was given by Benito Mussolini to Pietro Badoglio, commander-in-chief of the Italian armed forces, and Mario Roatta, acting chief of staff of the army, on 15 October with the expectation that the attack would commence within 12 days. Badoglio and Roatta were appalled given that, acting on his orders, they had recently demobilised 600,000 men three weeks prior to provide labor for the harvest.[52] Given the expected requirement of at least 20 divisions to facilitate success, the fact that only eight divisions were currently in Albania and the fact that the Albanian ports and connecting infrastructure were inadequate, proper preparation would have required at least three months.[52] Nonetheless, D-day was set at dawn on 26 October.

The Italian war plan, codenamed Emergenza G ("Contingency G[reece]"),[2] called for the occupation of the country in three phases. The first would be the occupation of Epirus and the Ionian Islands, followed by a thrust into Western Macedonia after the arrival of reinforcements, and concluded with movements towards Thessaloniki, aimed at capturing northern Greece. Afterwards, the remainder of the country would be occupied. Subsidiary attacks were to be carried out against the Ionian Islands and it was hoped that Bulgaria would intervene and pin down the Greek forces in Eastern Macedonia.

The Italian High Command accorded an Army Corps to each theatre, formed from the existing forces occupying Albania. The stronger XXV Ciamuria Corps in Epirus[53] consisted of the 23rd Ferrara (16,000 men, with 3,500 Albanian troops), the 51st Siena (9,000 men) Infantry Divisions, the 131st Centauro Armoured Division (4,000 men); the Corps was reinforced by 3rd Granatieri di Sardegna Regiment, the 6th Regiment Lancieri di Aosta, several cavalry squadrons of the 7th Regiment Lancieri di Milano, some artillery batteries and some hundreds of Albanian blackshirts battalions, all forming the brigade-sized "Littoral Group" (Raggruppamento Litorale) of some 5,000 men. In total, this was around 30,000 men and 163 L3 light tanks. They intended to drive towards Ioannina, flanked on the right by the Littoral Group along the coast, and to its left by the elite Julia Alpine Division, which would advance through the Pindus Mountains. The XXVI Corizza Corps in the Macedonian sector consisted of the 29th Piemonte (9,000 men), the 49th Parma (12,000 men) Infantry Divisions; the 19th Venezia Division (10,000 men) was moving from the Yugoslavian frontier: it first unit to reach the operation theatre was the 83rd Infantry Regiment. The total Italian forces in western Macedonian, once completed their deployment, was around 31,000 men. The 53rd Arezzo Division was later called in the area once the failure of the offensive become apparent. It was initially intended to maintain a defensive stance. In total, the force facing the Greeks comprised about 85,000 men under the command of Lt. General Sebastiano Visconti Prasca.

After the Italian occupation of Albania, the Greek General Staff had prepared the "IB" (Italy-Bulgaria) plan, anticipating a combined offensive by Italy and Bulgaria. The plan was essentially prescribing a defensive stance in Epirus, with a gradual retreat to the Arachthos River–Metsovo–Aliakmon River–Mt. Vermion line, while maintaining the possibility of a limited offensive in Western Macedonia. Two variants of the plan existed for the defence of Epirus, "IBa", calling for forward defence on the border line, and "IBb", for defence in an intermediate position. It was left to the judgment of the local commander, Maj. General Charalambos Katsimitros, to choose which plan to follow. A significant factor in the Greeks' favour was that they had managed to obtain intelligence about the approximate date of the attack and had just completed a limited mobilization in the areas facing the expected Italian attack.

The main Greek forces in the immediate area at the outbreak of the war were the 8th Infantry Division, fully mobilized and prepared for forward defence by its commander, Maj. Gen. Katsimitros, in Epirus and the Corps-sized Army Section of Western Macedonia or TSDM (ΤΣΔΜ, Τμήμα Στρατιάς Δυτικής Μακεδονίας), under Lt. Gen. Ioannis Pitsikas, including the "Pindus Detachment" (Απόσπασμα Πίνδου) of regimental size under Colonel Konstantinos Davakis, the 9th Infantry Division, and the 4th Infantry Brigade in Western Macedonia. The Greek forces amounted to about 35,000 men, but could be quickly reinforced by the neighbouring formations in southern Greece and Macedonia.

The Greek divisions had three regiments as opposed to two, meaning 50% more infantry,[54][55] and slightly more medium artillery and machine-guns than the Italians,[56] but they completely lacked tanks. The Italians could count on complete air superiority over the small Hellenic Royal Air Force. The majority of Greek equipment was still of World War I issue from countries like Belgium, Austria, and France, which were now under Axis occupation, creating adverse effects on the supply of spare parts and suitable ammunition. However, many senior Greek officers were veterans of a decade of almost continuous warfare, including the Balkan Wars of 1912–13, the First World War, and the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–22. Despite its limited means, the Greek Army had actively prepared itself for the forthcoming war during the late 1930s. In addition, Greek morale, contrary to Italian expectations, was high, with many eager to "avenge Tinos".

Stages of the campaign

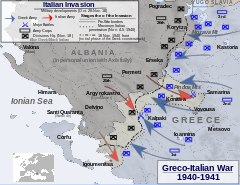

Initial Italian offensive (28 October 1940 – 13 November 1940)

_(8669103692).jpg)

The war started with Italian forces launching an invasion of Greece from Albanian territory. The attack was launched on the morning of 28 October, pushing back the Greek screening forces. The Ciamuria Corps, spearheaded by the Ferrara and Centauro divisions, attacked towards Elaia in Kalpaki. The tanks of the Centauro Division faced difficulties with the marshy terrain.[57]

On 31 October, the Italian Supreme Command announced that "[their] units continue to advance into Epirus and have reached the river Kalamas at several points. Unfavourable weather conditions and action by the retreating enemy are not slowing down the advances of our troops". In reality, the Italian offensive was carried out without conviction and without the advantage of surprise. Even air action was rendered ineffective by poor weather.[54] Under an uncertain leadership and divided by personal rivalries, the troops were already becoming exhausted. Adverse conditions at sea made it impossible to carry out a projected landing at Corfu.[33] By 1 November, the Italians had captured Konitsa and reached the Greek main line of defense. On that same day, the Albanian theatre was given priority over Africa by the Italian High Command.[58]

Only the littoral group on the western sector managed to advance slowly and secured a bridgehead over the Kalamas River on November 6.[57] However, despite repeated attacks, the Italians failed to break through the Greek defences in the Battle of Elaia–Kalamas, and the attacks were suspended on 9 November 1940.

A greater threat to the Greek positions was posed by the advance of the 10,800-strong[59] 3rd Julia Alpine Division over the Pindus Mountains towards Metsovo, which threatened to separate the Greek forces in Epirus from those in Macedonia. Julia achieved early success, breaking through the central sector of Col. Davakis' detachment of 2,000 men.[60] The Greek General Staff immediately ordered reinforcements into the area, which passed under the control of the II Greek Army Corps. The first Greek counteroffensive was launched on 31 October, but had little success. After covering 25 miles of mountain terrain in icy rain, Julia managed to capture Vovousa, 30 km north of Metsovo, on 2 November, but it had become clear that it lacked the manpower and the supplies to continue in the face of the arriving Greek reserves.[61]

Greek counterattacks resulted in the recapture of several villages, including Vovousa by 4 November, practically encircling "Julia". Gen. Prasca tried to reinforce it with the newly arrived 47th Bari Division, (which was originally intended for the invasion of Corfu), but it arrived too late to change the outcome. Over the next few days, the Alpini fought in atrocious weather conditions and under constant attacks by the Greek Cavalry Division led by Maj. Gen. Georgios Stanotas. However, on 8 November, Gen. Mario Girotti, the commander of Julia, was forced to order his units to begin their retreat via Mt. Smolikas towards Konitsa.

By 13 November, the Greek forces had cleared the sectors of Pindus and Epirus pushing the Italians back to the pre-war border, while in northwestern Macedonia they already gained footholds beyond the border.[62]

With the Italians inactive in western Macedonia, the Greek high command moved III Army Corps, which consisted of the 10th and 11th Infantry Divisions and the Cavalry Brigade, under Lt. Gen. Georgios Tsolakoglou, into the area on 31 October and ordered it to attack into Albania with the TSDM. For logistical reasons, this attack was successively postponed until 14 November.

The unexpected Greek resistance caught the Italian high command by surprise. Several divisions were hastily sent to Albania and plans for subsidiary attacks on Greek islands were scrapped. Enraged by the lack of progress, Mussolini reshuffled the command in Albania, replacing Prasca with his former Vice-Minister of War, General Ubaldo Soddu, on 9 November. Immediately upon arrival, Soddu ordered his forces to turn to the defensive. It was clear that the Italian invasion had failed. The performance of Albanians in blackshirt battalions was distinctly lackluster. The Italian commanders, including Mussolini, would later use the Albanians as scapegoats for the invasion's failure.[31] These battalions, named Tomorri and Gramshi, were formed and attached to the Italian army during the conflicts; however, the majority of them defected.[63]

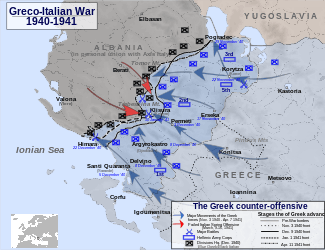

Greek counteroffensive (14 November 1940 – 10 January 1941)

Greek reserves started reaching the front in early November. Bulgarian inactivity allowed the Greek high command to transfer a majority of its divisions from the Greco-Bulgarian border to the Albanian front. This enabled Greek Commander-in-Chief Lt. Gen. Alexandros Papagos to establish numerical superiority by mid-November, prior to launching his counteroffensive. Walker[64] cites that the Greeks had a clear superiority of 250,000 men against 150,000 Italians by the time of the Greek counterattacks. Only six of the Italian divisions, the Alpini, were trained and equipped for mountainous conditions. Bauer[61] states that by 12 November, Gen. Papagos had at the front over 100 infantry battalions fighting in terrain to which they were accustomed, compared with less than 50 Italian battalions.

TSDM and the III Corps, continuously reinforced with units from all over northern Greece, launched their attack on 14 November in the direction of Korçë. After bitter fighting on the fortified frontier line, the Greeks broke through on 17 November, entering Korçë on 22 November. However, due to indecisiveness among the Greek high command, the Italians were allowed to break contact and regroup, avoiding a complete collapse.

The attack from western Macedonia was combined with a general offensive along the entire front.[65] The I and the II Corps advanced in Epirus and, after hard fighting, captured Sarandë, Pogradec, and Gjirokastër by early December and Himarë on 22 December. In doing so, they occupied practically the entire area of southern Albania known as "Northern Epirus". Two final Greek successes included the capturing of the strategically important and heavily fortified Klisura Pass on 10 January by II Corps, followed by the capture of the Trebeshinë massif in early February.

Stalemate and Italian Spring offensive

The Greeks did not succeed in breaking through towards Berat and Vlorë, during the winter. In the fight for Vlorë, the Italians suffered serious losses to their Lupi di Toscana, Julia, Pinerolo, and Pusteria divisions. By the end of January, with Italy finally gaining numerical superiority and the Greeks' bad logistical situation, the Greek advance was finally stopped. Meanwhile, Gen. Soddu was replaced by Gen. Ugo Cavallero in mid-December. On 4 March, the British sent their first convoy of troops and supplies to Greece under the orders of Lt. Gen. Sir Henry Maitland Wilson. Their forces consisted of four divisions, two of them armoured,[66] but the 57,000 soldiers did not reach the front in time to fight.

The stalemate continued, despite local actions, as neither opponent was strong enough to launch a major attack. Despite their gains, the Greeks were in a precarious position, as they had virtually stripped their northern frontier of weapons and men in order to sustain the Albanian front, making them too weak to resist a possible German attack via Bulgaria.

The Italians, on the other hand, wishing to achieve success on the Albanian front before the impending German intervention, gathered their forces to launch a new offensive, code-named Primavera ("Spring"). The Italians assembled 17 divisions opposite the Greeks' 13 and, under Benito Mussolini's personal supervision, launched a determined attack against the Klisura Pass. The assault lasted from 9 to 20 March, but failed to dislodge the Greeks. The attack only resulted in small gains like Himarë, the area of Mali Harza, and Mt. Trebescini near Berat.[13] From that moment until the German attack on 6 April, the stalemate continued, with operations on both sides scaled down.

German intervention

The beginnings of German intervention in Greece

Incremental British involvement in Greece meant that the Germans were taking more of an interest in the precarious and fragile situation in Greece. They began to draft plans for a possible military intervention. Whilst on 1st November, Hitler had decided to let Italy fight its war with Greece alone, the continual encroachment of the British in the affairs of Greece and reports that they were building air bases on Lemnos and and Salonika, finally forced Hitler to order his generals to draw up plans for a speedy march into Turkish Thrace and northern Greece if and when required.[67] On November 18, Hitler issued Directive 18 which specifically mentioned the operation of the Luftwaffe against targets in the eastern Mediterranean, which included "British bases that might threaten the Romanian oil-fields."[68]

Thrust across Southern Yugoslavia and drive to Thessaloniki

Prime Minister Metaxas tried desperately to prevent a war between Greece and Germany and hoped that he could persuade the Germans to act as mediators to help end the war with the Italians in Albania.[69] He tried to convince the Germans that Greece would remain either neutral or surprisingly, even pro-Axis. [70] Thus he allowed "discreet approaches" to be made to Berlin. [71] Greek generals were also desperate to avoid hostilities with Germany for they knew they were no match against the Wehrmacht, so much so that King George had to dismiss several of them for abject defeatism.[72]

In anticipation of the German attack, the British and some Greeks urged a withdrawal of the army of Epirus to spare badly needed troops and equipment to repel the Germans. However, national sentiment forbade the abandonment of such hard-won positions. The mentality that retreat in the face of the Italians would be disgraceful and overriding military logic caused them to ignore the British warning. Therefore, 15 divisions, the bulk of the Greek army, were left deep in Albania as German forces approached. General Wilson derided this reluctance as "the fetishistic doctrine that not a yard of ground should be yielded to the Italians"; only six of the 21 Greek divisions were left to oppose the German attack.[73][74]

On 6 April, the Italians re-commenced their offensive in Albania in coordination with the German Operation Marita. With the Greek retreat beginning on 12 April, the Italian 9th Army entered Korçë on 14 April and Ersekë three days later. On 19 April, the Italians occupied the Greek shores of Lake Prespa, and on 22 April, the Bersaglieri Regiment reached the bridge of the border village of Perati, crossing into Greek territory the next day.

Withdrawal and surrender of the Greek army in Epirus

In view of the rapid progress of the German troops and the capture of Thessaloniki on 9 April, on 12 April the Greek General Headquarters in Athens gave the order of retreat to the Greek forces on the Albanian front.[75] The Greek commanders in Albania were aware that, given the continued Italian pressure, the lack of motor transport and pack animals, the physical exhaustion of the Greek army and the poor transport network of Epirus, any retreat was likely to end up in disintegration. They had pressed in vain for a retreat already before the start of the German attack, but now they petitioned the senior front commander, Lt. General Ioannis Pitsikas, to surrender. Although Pitsikas forbade such talk, he notified Papagos of these developments and urged a solution that would secure "the salvation and honour of our victorious Army".[76][77] Indeed the orders to retreat, coupled with the disheartening news of the Yugoslav collapse and of the rapid German advance, led to a breakdown of the morale of the Greek troops, many of whom had been fighting without reprieve for five months and were now forced to abandon hard-won ground. By 15 April, the divisions of II Army Corps, beginning with the Cretan 5th Division, began to disintegrate, with men and even entire units abandoning their positions.[76][78][79]

On 16 April, Pitsikas reported to Papagos that signs of disintegration had begun to appear among the divisions of I Corps as well, and begged him to "save the army from the Italians", i.e. to be allowed to capitulate to the Germans before the military situation collapsed completely. On the next day, the Western Macedonia Army Section under Lt. General Georgios Tsolakoglou was renamed to III Army Corps and placed under Pitsikas' command as well. The three corps commanders, along with the metropolitan bishop of Ioannina, Spyridon, pressured Pitsikas to unilaterally begin negotiations with the Germans.[78][80][81] When he refused, the others decided to bypass him and selected Tsolakoglou, as the senior of the three generals, to carry out the task. Tsolakoglou delayed for a few days, sending his chief of staff to Athens to secure permission from Papagos. The chief of staff reported the chaos in Athens and urged his commander to take the initiative in a message that implied permission by Papagos, although this was not in fact the case. On 20 April, Tsolakoglou contacted the commander of the nearest German unit, the LSSAH brigade, Sepp Dietrich, to offer surrender. The protocol of surrender was signed at 18:00 of the same day between Tsolakoglou and Dietrich. Presented with the fait accompli, Pitsikas was informed an hour later and resigned his command.[82][83][84] World War II historian John Keegan writes that Tsolakoglou "was so determined, however, to deny the Italians the satisfaction of a victory they had not earned that, once the hopelessness of his position became apparent to him, he opened quite unauthorised parley with the commander of the German SS division opposite him, Sepp Dietrich, to arrange a surrender to the Germans alone."[85] The original surrender document did not include the Italians and "came as an unwelcome and most humiliating blow" to the Italians.[86] Upon signing the agreement, List agreed with Tsolakoglou that the Italians should not be allowed to enter Greece. Some units of the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, were so impressed with the bravery of the Greek army that they assumed positions between the Greek and Italian armies at a border crossing called "Ponte Berati" with the aim of preventing the Italian army from crossing into Greece.[86] However, Hitler valued the Italo-German alliance much more highly than Greece and wanted to move his army north as soon as possible. So he quickly countermanded List, insisting that the German-Italian relationship was of paramount importance and not Greece. [87] So on the 13th May, he announced his intention to leave the main occupation and responsibility for Greece to his Italian allies.[88]

According to historian Mark Mazower, these events "came as an unwelcome and humiliating blow, for Mussolini had been desperately anxious to beat the Greeks before the Wehrmacht arrived". Mazower further notes that Mussolini became "enraged" when he learned of the terms of the agreement and "became even more incensed" when he understood that the agreement was actually a surrender and not just a ceasefire.[86] Upon learning of the developments Mussolini summoned the German attaché in Rome and threatened that he would not observe the ceasefire if the Italians were not also parties to the surrender agreement.[86] Mussolini was worried that the Greeks would claim that they had not surrendered to the Italians. Eventually the Greeks, did claim just that, and according to Mazower, "quite justifiably" so.[86] Outraged by this decision, Mussolini ordered counterattacks against the Greek forces which had just surrendered, and to Mussolini's embarrassment, these counterattacks were repulsed. Only after a personal request from Mussolini to Hitler, the German dictator agreed to help Mussolini yet again, albeit very reluctantly, and Italy was allowed as a party in the armistice agreement on April 23.[86][89] In recognition of the valour displayed by Greek forces, the enlisted men were allowed to return to their homes (rather than being confined to POW camps) and officers were allowed to keep their sidearms.[90]

Triple occupation

For propaganda purposes, Mussolini decided to preempt the announcement of the official surrender agreement by announcing ahead of time through the Italian radio that the "surrender had been tendered to the commander of the Italian Eleventh Army" and that the rest of the details would be ironed out with "our German allies".[86] The Italian broadcast had the effect of further straining the German-Italian relations.[86] According to Mazower, "Wehrmacht felt utter contempt" toward their Italian allies. Field Marshal Keitel had remarked at the time that "The Italians were just like children wanting to gobble up everything". In the vicinity of Patras, members of the Leibstandarte reacting to the salutes of some Italian women responded by "Brutta Italia, Heil Hitler".[86]

Mussolini's occupation plans for Greece were unclear and this was revealed when the Italian Foreign minister gave some vague replies on 21 April to the Germans regarding the territorial claims of the Italians against Greece. He told them that he thought that Mussolini had plans of annexing parts of Northern Greece and the Ionian islands.[86] Many of the territories that Mussolini coveted were mountainous villages with poor infrastructure, and their annexation had little strategic or political benefit for the new Roman Empire that Mussolini envisioned to build in Greece.[86] The Italian military attaché in Berlin perceiving that the vague Italian plans would not be acceptable to the Germans advised the Italian government to "accelerate our occupation even by sea to forestall the German troops".[86] At the second round of surrender talks in Salonica, Benzler, the German chief Foreign Office delegate attached to List's 12th army, told the Italian negotiator in no uncertain terms that the Italians should assist in the formation of the new Greek government under occupation and refused the suggestions by the Italian negotiator Anfuso to include provisions about future territorial demands by the Italians into the surrender agreement, mentioning that he did not want to scare General Tsolakoglou with such clauses.[86] Faced with the German response, Anfuso complained half-heartedly that given Greece's "total defeat" the agreement should have been that of a "pure and simple occupation" as the one in Poland's case.[86] But the German evaluation of Greece differed significantly from that of Poland on strategic and racial grounds. In addition the Germans, starting with Hitler, admired the Greeks for their bravery.[86]

Naval operations

At the outbreak of hostilities, the Royal Hellenic Navy was composed of the old cruiser Averof, 4 old Theria class, 4 relatively modern Dardo class, and 2 new G class destroyers, several torpedo boats, and 6 old submarines. These ships, whose role was primarily limited to patrol and convoy escort duties in the Aegean Sea, faced up against the far larger Italian Regia Marina.

Nevertheless, the Greek ships also carried out limited offensive operations against Italian shipping in the Strait of Otranto. The destroyers carried out three bold, but fruitless night-time raids on 14 November 1940, 15 December 1940, and 4 January 1941. The main successes came from the submarines, which managed to sink some Italian transports. On the Italian side, although the Regia Marina suffered minor losses in capital ships from the Royal Navy during the Taranto raid, Italian cruisers and destroyers continued to operate covering the convoys between Italy and Albania. On 28 November, an Italian squadron heavily bombarded Corfu, while, on 18 December and 4 March, Italian task forces shelled Greek coastal positions in Albania.

From January 1941, the RHN's main task was the escort of convoys to and from Alexandria, in cooperation with the British Royal Navy. As the transportation of the British Expeditionary Corps began in early March, the Italian Fleet decided to sortie against them. Well informed by Ultra intercepts, the British fleet intercepted and narrowly defeated the Italians at the Battle of Cape Matapan on 28 March.

With the start of the German offensive on 6 April, the situation changed rapidly. During the Battle of Crete, the Italian 50th Infantry Division Regina captured Sitia on 28 May and Italian bombers from 41 Gruppo on Rhodes.[91][92]attacked and sank the destroyer Juno.[93] German and Italian control of the air caused heavy casualties to the Greek and British navies, and the occupation of the mainland and later Crete by the Wehrmacht signaled the end of Allied surface operations in Greek waters until the Dodecanese Campaign of 1943.

Aftermath

On 30 April, troops from the Italian 185th Airborne Division Folgore dropped in on Zakynthos, Cephalonia and Lefkada, capturing the Greek islands and the 250-strong garrison.[94]That same day, Italian troops captured Corfu and a Greek battalion that had regrouped in the local woods. [95]On 3 May, after the final conquest of Crete, an imposing German-Italian parade in Athens celebrated the Axis victory. It wasn't until after the victory in Greece and Yugoslavia that Mussolini started to talk and boast in his propaganda about the Italian Mare Nostrum.

The Italian soldiers, according to Major-General Charalambos Katsimitros, had fought well:

The Italian infantry under competent command fought well; the Italian soldier, especially in defence and in capable hands, was a very good warrior.[96]

The Greek struggle received exuberant praise at the time. Most prominent is the quote of Winston Churchill:

"Hence we will not say that Greeks fight like heroes, but that heroes fight like Greeks."[97]

French general Charles de Gaulle was among those who praised the fierceness of the Greek resistance. In an official notice released to coincide with the Greek national celebration of the Day of Independence, De Gaulle expressed his admiration for the heroic Greek resistance:

In the name of the captured yet still alive French people, France wants to send her greetings to the Greek people who are fighting for their freedom. The 25 March 1941 finds Greece in the peak of their heroic struggle and in the top of their glory. Since the Battle of Salamis, Greece had not achieved the greatness and the glory which today holds.[98]

Greece's siding with the Allies also contributed to its annexation of the Italian-occupied but Greek-populated Dodecanese islands in 1947.

The occupation of Greece, during which civilians suffered terrible hardships, and died from privation and hunger, proved to be a difficult and costly task. It led to the creation of several resistance groups, which launched guerilla attacks against the occupying forces and set up espionage networks.[99] The 1940 war, popularly referred to as the Épos toú Saránda (Greek: Έπος του Σαράντα, "Epic of '40") in Greece, and the resistance of the Greeks to the Axis Powers is celebrated to this day in Greece every year. 28 October, the day of Ioannis Metaxas' rejection of the Italian ultimatum, named Ohi Day, Greek for "Day of No", is a day of national celebration in Greece.

A military parade takes place in Thessaloniki and student parades take place in Athens and other cities to coincide with the city's anniversary of liberation during the First Balkan War and the feast of its patron saint, St. Demetrius. For several days, many buildings in Greece, public and private, display the Greek flag. In the days preceding the anniversary, television and radio often feature historical films and documentaries about 1940 or broadcast Greek patriotic songs, especially those of Sofia Vembo, a singer whose songs gained immense popularity during the war. It serves also as a day of remembrance for the "dark years" of the Axis occupation of Greece from 1941 to 1944.

Consequences

Hitler blamed Mussolini’s "Greek fiasco" for his failed campaign in Russia. ‘But for the difficulties created for us by the Italians and their idiotic campaign in Greece’, he commented in mid-February 1945, ‘I should have attacked Russia a few weeks earlier,’ he later said. Hitler noted that, the ‘pointless campaign in Greece’, Germany was not notified in advance of the impending attack, which ‘compelled us, contrary to all our plans, to intervene in the Balkans, and that in its turn led to a catastrophic delay in the launching of our attack on Russia. We were compelled to expend some of our best divisions there. And as a net result we were then forced to occupy vast territories in which, but for this stupid show, the presence of our troops would have been quite unnecessary’. ‘We have no luck with the Latin races’, he complained afterwards. Mussolini took advantage of Hitler's preoccupation with Spain and France ‘to set in motion his disastrous campaign against Greece’.[100] As an explanation for Germany's defeat in the Soviet Union, Andreas Hillgruber, has accused Hitler of trying to deflect blame for his country's defeat from himself to his ally, Italy.[101]

Historian Ian Kershaw notes that the five week delay in launching ‘Barbarossa’, caused by the unusually wet weather in May 1941, is deemed not in itself decisive. For Kershaw, the reasons for the ultimate failure of ‘Barbarossa’ lay in the arrogance of the German war goals, in particular the planning flaws and resource limitations that caused problems for the operation from the start. He adds that the German invasion into Greece in spring 1941 didn't cause significant damage to tanks and other vehicles needed for ‘Barbarossa’, the equipment diverted to Greece being used on the southern flank of the attack on the Soviet Union.[102] Von Rintelen emphasizes that although the diversion of German resources into Greece just prior to the attack on the Soviet Union did little for the latter operation, Italy's invasion of Greece did not undermine 'Barbarossa' before the operation started. Instead, Italy's invasion of Greece was to have serious consequences for its ongoing campaign in North Africa. Moreover, Italy would have been in a better position to execute its North African campaign had it initially occupied Tunis and Malta.[103]

During and after the October attack on Greece, Italian resources were dedicated to fighting in the Greek front rather than assist the Axis war effort in North Africa. From the start of the Italian attack in October 1940 to May 1941, the quantity of soldiers, merchant ships, escort vessels and weapons which Italy allocated to the Greek front was multiple times higher than the quantities Italy sent to support its campaign in North Africa.[104]

When the British counterattack began in December 1940, this diversion of resources by Italy has adverse results in the North African war front. The German naval staff by 14 November 1940 issued a critical appraisal of the Italian strategy: ‘Conditions for the Italian Libyan offensive against Egypt have deteriorated. The Naval Staff is of the opinion that Italy will never carry out the Egyptian offensive’. Had the Egyptian offensive succeeded, it would have strengthened the Axis military position in North Africa because it would have allowed it control of the Suez Canal.[105] The German evaluation of Italy's Greek offensive also stated:

The Italian offensive against Greece is decidedly a serious strategic blunder; in view of the anticipated British counteractions it may have an adverse effect on further developments in the Eastern Mediterranean and in the African area, and thus on all future warfare ... The Naval Staff is convinced that the result of the offensive against the Alexandria–Suez area and the development of the situation in the Mediterranean, with their effects on the African and Middle Eastern areas, is of decisive importance for the outcome of the war … The Italian armed forces have neither the leadership nor the military efficiency to carry the required operations in the Mediterranean area to a successful conclusion with the necessary speed and decision. A successful attack against Egypt by the Italians alone can also scarcely be expected now.[106]

According to Kershaw, Italy's ambitions of becoming a great power were put to an end, due to the combination of the failed Greek campaign, the loss of its fleet at Taranto and Italy's retreat and failure in the North African front. After these failures, Mussolini's exploitation of Italian ambitions for political gain had come to an end. By failing to deliver, his stature amongst the political elites of Italy was diminished.[107] Mussolini's failure caused Italy to become even more subservient to the Germans. According to Kershaw, when things started unravelling in Italy's war effort, the Italian political elites did not accept their share of the responsibility for the failures, although they were eager to take credit for the successes, when things were going well. Kershaw concludes: "The stupidity of Mussolini's choice reflected the despot's extreme individual inadequacies. At the same time it was additionally the idiocy of a political framework".[108]

Sadkovich asserts that while "the Italo-Greek war was a crucial turning point in the Second World War, its impact has been exaggerated by most authors, who are content with the superficial observation that it ended Mussolini's parallel war.".[109] De Felice states that "public confidence oscillated with Italian defeats and victories, rising with Axis victories in early 1941. This seems to have been the case not only for the public, but for the armed forces as well, which rallied from a jarring setback in Greece".[110]

References

- ↑ Richter (1998), 119, 144

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Mario Cervi, Storia della guerra di Grecia, Oscar Mondadori, 1969, page 129

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Hellenic Air Force History accessed 25 March 2008

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Mario Montanari, La campagna di Grecia, Rome 1980, page 805

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Giorgio Rochat, Le guerre italiane 1935–1943. Dall'impero d'Etiopia alla disfatta, Einaudi, 2005, p. 279

- ↑ Mario Cervi, Storia della guerra di Grecia, BUR, 2005, page 267

- ↑ Rodogno (2006), pages 446

- ↑ Ewer, Peter (2008). Forgotten ANZACS : the campaign in Greece, 1941. Carlton North, Vic.: Scribe Publications. p. 75. ISBN 9781921215292.

- ↑ Greek: Ελληνοϊταλικός Πόλεμος, Ellinoitalikós Pólemos, or Πόλεμος του Σαράντα, Pólemos tou Saránda.

- ↑ Italian: Guerra di Grecia.

- ↑ Ciano (1946), p. 247

- ↑ Svolopoulos (1997), p. 272

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Buell (2002), pages 76

- ↑ Peter Neville (2013). Historical Dictionary of British Foreign Policy. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8108-7173-1.

Mussolini's invasion failed.

- ↑ William J. Moylan. The King Of Terror. Xlibris Corporation. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4797-9704-2.

Hitler was against Mussolini's invasion, (as it would require German troops' help later on), but Mussolini continued without...

- ↑ David W. Wragg (2003). Malta: The Last Great Siege : the George Cross Island's Battle for Survival 1940-1943. Casemate Publishers. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-85052-990-6.

When Italy's invasion of Egypt failed miserably, and his forces failed in Yugoslavia and Greece, Mussolini needed the Germans to help him out. The Germans had watched with amazement and scorn at the destruction inflicted on the Italian ...

- ↑ Peter Neville (2004). Mussolini. Psychology Press. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-415-24990-4.

Seeing his ally floundering from one disaster to another Hitler felt obliged to intervene in March 1941. Mussolini was reluctant to accept German help, especially against the Greeks (in Africa, at least, he could pretend that he was worsted by another great power), but he had little real option. Simultaneously the Germans had invaded Yugoslavia, devastating Belgrade from the air because the Yugoslavs had ... but Mussolini was further humiliated when the Greeks declined to surrender to an enemy that had totally failed to hold an inch of their territory.

- ↑ Andreas Hillgruber, Hitlers Strategie. Politik und Kriegführung 1940–1941, 3rd edn., Bonn, 1993, p. 506-11

- ↑ Kershaw 2007, p. 178-182

- ↑ von Rintelen, Enno, Mussolini als Bundesgenosse. Erinnerungen des deutschen Militärattachés in Rom 1936–1943, Tübingen/Stuttgart, 1951.pp. 90-99

- ↑ According to data presented at the 1919 Paris Conference, the ethnic Greek minority numbered 120.000.

- ↑ Verzijl (1970), p. 396

- ↑ Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism 1914–45, London, 1995, p. 383; I.C.B. Dear and M. R.D. Foot (eds.), The Oxford Companion to the Second World War, Oxford/New York, 1995, p. 583.

- ↑ Quoted from MacGregor Knox, Mussolini Unleashed 1939–1941. Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy’s Last War, paperback edn., Cambridge, 1986, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Ciano’s Diary 1939–1943, ed. Malcolm Muggeridge, London, 1947, pp. 45–6.

- ↑ Ciano’s Diary, pp. 134–6; Enno von Rintelen, Mussolini als Bundesgenosse. Erinnerungen des deutschen Militärattachés in Rom 1936–1943, Tübingen/Stuttgart, 1951, p. 71; Knox, Mussolini Unleashed, p. 43. On the concept of ‘non-belligerency’, see Neville Wylie (ed.), European Neutrals and Non-Belligerents during the Second World War, Cambridge, 2002, p. 4.

- ↑ Mario Cervi, The Hollow Legions. Mussolini’s Blunder in Greece, 1940–1941, London, 1972, pp. 7–10; also Mack Smith, Mussolini, p. 271. Ciano had written in his diary on 12 September 1939, that Mussolini had "given instructions for an understanding with Greece, a country too poor for us to covet" (Ciano’s Diary, p. 151).

- ↑ Pietro Badoglio, Italy in the Second World War. Memories and Documents, London/New York/Toronto, 1948, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War, vol. 2: Their Finest Hour, London, 1949, p. 106.

- ↑ Vickers, Miranda. The Cham Issue – Albanian National & Property Claims in Greece. Paper prepared for the British MoD, Defence Academy, 2002.ISBN 1-903584-76-0

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (1999). Albania at War, 1939–1945. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1-85065-531-2.

- ↑ Ciano (1947)

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Buell (2002), pages 54

- ↑ Knox (2000), p. 79

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Sadkovich, (1993), The Italo-Greek War in Context, pp.439- 445.

- ↑ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (1 January 2004). History of World War II. Marshall Cavendish. p. 921. ISBN 978-0-7614-7485-2.

German forces enter Romania to secure the Ploesti oil fields. ...

- ↑ Ciano (1947), Page 297

- ↑ Knox, Mussolini Unleashed, p. 202; Martin van Creveld, Hitler’s Strategy 1940–1941. The Balkan Clue, Cambridge, 1973, p. 34.

- ↑ Kershaw 2007, p. 170.

- ↑ Guy Wint; John Pritchard; Peter Calvocoressi (2 September 1999). The Penguin History of the Second World War. Penguin Books Limited. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-14-195988-7.

- ↑ Regan, Geoffrey. More Military Blunders. p. 83.

- ↑ Regan, Geoffrey. More Military Blunders. p. 54.

- ↑ Buell (2002), p. 52

- ↑ "Cronologia del Mondo". Cronologia.leonardo.it. 1940-11-02. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ↑ Knox, MacGregor (1986). Mussolini Unleashed, 1939–1941: Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy's Last War. Cambridge University Press. p. 261. ISBN 0-521-33835-2.

- ↑ Hadjipateras (1996)

- ↑ Goulis and Maïdis (1967)

- ↑ Rodogno (2006), p. 103

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Rodogno (2006), p. 104

- ↑ Rodogno (2006), pp. 84–85

- ↑ Knox, MacGregor (1986). Mussolini Unleashed, 1939–1941: Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy's Last War. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 0-521-33835-2.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Bauer (2000), p. 99

- ↑ Army History Directorate (Greece). An abridged history of the Greek-Italian and Greek-German war, 1940–1941. Hellenic Army General Staff, 1997. ISBN 978-960-7897-01-5, p. 28 "This HX included the XXV Army Corps of Tsamouria..."

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Walker (2003), pp. 22–23

- ↑ Italian Army OrBat, at Comando Supremo

- ↑ Buell (2002), p. 37

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Plowman (2013), p. 12.

- ↑ Knox (2000), p. 80

- ↑ Willingham (2005), p. 24

- ↑ Carr (2013), p. 42

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Bauer (2000), p. 105

- ↑ Hellenic Army General Staff: p. 71

- ↑ Anamali, Skënder and Prifti, Kristaq. Historia e popullit shqiptar në katër vëllime. Botimet Toena, 2002, ISBN 99927-1-622-3.

- ↑ Walker (2003), p. 28

- ↑ "Zeto Hellas". TIME magazine. 2 December 1940. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ↑ Buell (2002), p. 75

- ↑ Stockings, Dr Craig, Hanson, Dr Eleanor (2013,). Swastika over the Acropolis. Leiden, The Netherlands. pp. pp.61–62. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Stockings, Dr Craig, Hanson, Dr Eleanor (2013). Swastika over Athens. Leiden, The Netherlands. pp. pp.61–62.

- ↑ Mazower, 1993, p.15

- ↑ Mazower, 1993, p.15.

- ↑ Mazower, 1993, p.15.

- ↑ Mazower, 1993, p.16.

- ↑ De Felice (1990), p. 125

- ↑ "In anticipation of the German attack, the British and some Greeks urged a withdrawal of the army of Epirus to spare badly needed troops and equipment to repel the Germans. However, national sentiment forbade the abandonment of such hard-won positions. The mentality that retreat in the face of the Italians would be disgraceful and overriding military logic caused them to ignore the British warning. Therefore, 15 divisions, the bulk of the Greek army, were left deep in Albania as German forces approached.derided this reluctance as "the fetishistic doctrine that not a yard of ground should be yielded to the Italians"; only six of the 21 Greek divisions were left to oppose the German attack. As a result of their poor deployment, the Greeks opposed the Italians with 14 divisions. They only had seven week divisions left to oppose the German Army, which was the best in the world at that time. In additions, the Greek Air Force had been in combat for months and had suffered such heavy losses on the Albanian Front that it was virtually nonoperational by April 1941." The Rise of the Wehrmacht: Vol. 1, Samuel W. Mitcham, p.394, ABC-CLIO, 2008

- ↑ Koliopoulos 1978, p. 444.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Koliopoulos 1978, p. 446.

- ↑ Stockings & Hancock 2013, pp. 225–227, 282.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Gedeon 2001, p. 33.

- ↑ Stockings & Hancock 2013, p. 258.

- ↑ Koliopoulos 1978, pp. 448.

- ↑ Stockings & Hancock 2013, pp. 282–283, 382.

- ↑ Koliopoulos 1978, pp. 448–450.

- ↑ Gedeon 2001, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Stockings & Hancock 2013, pp. 383–384, 396–398, 401–402.

- ↑ Keegan, p. 157

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 86.3 86.4 86.5 86.6 86.7 86.8 86.9 86.10 86.11 86.12 86.13 86.14 Mark Mazower (2001). Inside Hitler's Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941-44. Yale University Press. pp. 16–19. ISBN 978-0-300-08923-3.

Some detachments of the Leibstandarte, impressed by the brave performance of the Greek army, went so far as to block the Italians by stationing themselves between Greek and Italian units at a border crossing called Ponte Berati. [...] At first he was not disappointed, for List agreed that the Italian forces should not be allowed south across the border into Greece. [...] On learning that List had negotiated a surrender not just a ceasefire. the Duce became even more incensed. Page 16

- ↑ Mazower, 2001, p.20

- ↑ Mazower, 2001, p.20

- ↑ Keegan, P. 158

- ↑ Charles Messenger (2001). Hitler's Gladiator: The Life and Wars of Panzer Army Commander Sepp Dietrich. Brassey's Defence Publishers. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-57488-315-2.

Dietrich also chivalrously allowed the Greek officers to return to their homes because he feared that otherwise the ... all soldiers being now transferred to prisoner of war camp, although officers were still allowed to keep their sidearms, and .

- ↑ "Italian bombers from 41 Gruppo on Rhodes sank one destroyer." Why Air Forces Fail: The Anatomy of Defeat, Robin Higham, p. 166, University Press of Kentucky, 2006.

- ↑ "Axis air attacks were a constant threat to British Royal Navy ships around Crete. On one occasion, five Italian Cant Z1007 bombers sank the British destroyer HMS Juno." Regio Esercito: The Italian Royal Army in Mussolini's Wars, 1935-1943, p. 71, Patrick Cloutier, Lulu, 2013.

- ↑ "A single Italian Kingfisher scored precision hits on the lead enemy destroyer, HMS Juno, which exploded and sank southeast of the Aegean island, allowing German naval forces to make their landngs unopposed at sea." The Axis Air Forces: Flying in Support of the German Luftwaffe, Frank Joseph, p. 33, ABC-CLIO, 2011.

- ↑ German Airborne Divisions: Mediterranean Theatre 1942-45, Bruce Quarrie., p. 51, Osprey Publishing, 2013

- ↑ Scritti scelti sul potere aereo e l'aviazione d'assalto, 1920-1970: Il periodo tra le due guerre e la Seconda Guerra Mondiale, 1920-1943, Amedeo Mecozzi, p. 408, Aeronautica militare, Ufficio Storico, 2006

- ↑ The Defence and Fall of Greece 1940-1941, John Carr, p. 62, Pen and Sword, 2013

- ↑ Pilavios, Konstantinos (Director); Tomai, Fotini (Texts & Presentation) (25 October 2010). The Heroes Fight like Greeks – Greece during the Second World War (Motion Picture) (in Greek). Athens: Service of Diplomatic and Historical Archives of the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Event occurs at 51 sec. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ↑ Fafalios and Hadjipateras, p. 157

- ↑ Carlton (1992), 136

- ↑ The Testament of Adolf Hitler. The Hitler–Bormann Documents February–April 1945, ed. François Genoud, London, 1961, pp. 65, 72–3, 81. For textual problems with this source, see Ian Kershaw, Hitler, 1936–1945. Nemesis, London, 2000, n. 121, pp. 1024–5.

- ↑ See Andreas Hillgruber, Hitlers Strategie. Politik und Kriegführung 1940–1941, 3rd edn., Bonn, 1993, p. 506 n. 26.

- ↑ Kershaw 2007, p. 178.

- ↑ Rintelen, pp. 90, 92–3, 98–9, emphasizes from the German point of view the strategic mistake of not taking Malta.

- ↑ James J. Sadkovich, ‘The Italo-Greek War in Context. Italian Priorities and Axis Diplomacy’, Journal of Contemporary History, 28 (1993), pp. 439–64, at p. 440, and see also p. 455.

- ↑ Kershaw 2007, p. 179.

- ↑ Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs 1939–1945, London, 1990, pp. 154–5.

- ↑ Kershaw 2007, p. 180.

- ↑ Kershaw 2007, p. 183.

- ↑ Sadkovich, 'Italian Morale during the Italo-Greek War of 1940-1941',(1994) p.97.

- ↑ De Felice, cited in Sadkovich's 'Italian Morale during the Italo-Greek War of 1940-1941',(1994) p.97.

Sources

- Badoglio, Pietro, Italy in the Second World War. Memories and Documents, London/New York/Toronto, 1948.

- Bauer, Eddy; Young, Peter (general editor) (2000) [1979]. The History of World War II (Revised edition ed.). London, UK: Orbis Publishing. ISBN 1-85605-552-3.

- Beevor, Antony (1992). Crete: The Battle and the Resistance. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-016787-0.

- Buell, Hal. (2002). World War II, Album & Chronicle. New York: Tess Press. ISBN 1-57912-271-X.

- Carrier,Richard C, Hitler's Table Talk: Troubling Finds, German Studies Review, Vol. 26, No. 3 (Oct., 2003), pp. 561–576. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1432747.

- Carr, John C. (2013). The defence and fall of Greece 1940-1941. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781781591819.

- Cervi, Mario, The Hollow Legions. Mussolini’s Blunder in Greece, 1940–1941, London, 1972.

- Ceva, Lucio, 'La campagna di Russia nel quadro strategico della guerra fascista', Politico, 1979, and La condotta italiana della guerra: Cavallero e il Comando supremo 1941-1942, Milan, 1975.

- Churchill, Winston S., The Second World War, vol. 1: The Gathering Storm, London, 1948.

- —— The Second World War, vol. 2: Their Finest Hour, London, 1949.

- Ciano’s Diary 1939–1943, ed. Malcolm Muggeridge, London, 1947.

- Ciano’s Diplomatic Papers, ed. Malcolm Muggeridge, London, 1948.

- van Creveld, Martin, ‘25 October 1940. A Historical Puzzle’, Journal of Contemporary History, 6 (1971).

- —— Hitler’s Strategy 1940–1941. The Balkan Clue, Cambridge, 1973.

- —— ‘Prelude to Disaster. The British Decision to Aid Greece, 1940–41’, Journal of Contemporary History, 9 (1974).

- Dear, I.C.B., and Foot, M.R.D. (eds.), The Oxford Companion to the Second World War, Oxford/New York, 1995.

- De Felice, Renzo (1990). Mussolini l'Alleato: Italia in guerra 1940–1943. Torino: Rizzoli Ed.

- Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs 1939–1945, London, 1990.

- Gedeon, Dimitrios (2001). "Ο Ελληνοϊταλικός Πόλεμος 1940-41: Οι χερσαίες επιχειρήσεις". Ο Ελληνικός Στρατός και το Έπος της Βορείου Ηπείρου. Periskopio. pp. 4–35. ISBN 960-86822-5-8.

- Goulis and Maïdis, Ο Δεύτερος Παγκόσμιος Πόλεμος (The Second World War), (in Greek) (Filologiki G. Bibi, 1967)

- Hadjipateras, C.N., Greece 1940–41 Eyewitnessed, (Efstathiadis Group, 1996) ISBN 960-226-533-7

- Hellenic Army General Staff (1997). An Abridged History of the Greek-Italian and Greek-German War, 1940–1941 (Land Operations). Athens: Army History Directorate Editions. OCLC 45409635.

- Hillgruber, Andreas, Hitlers Strategie. Politik und Kriegführung 1940–1941, 3rd edn., Bonn, 1993.

- Keegan, John (2005). The Second World War. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-303573-8.

- Kershaw, Ian (2007). Fateful Choices: Ten Decisions that Changed the World, 1940-1941. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9712-5. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Kershaw, Ian, Hitler, 1936–1945. Nemesis, London, 2000.

- Kirchubel, Robert (2005). "Opposing Plans". Operation Barbarossa 1941. 2: Army Group North. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-857-X.

- Koliopoulos, Ioannis (1978). "Ο Πόλεμος του 1940/1941". Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος ΙΕ′: Νεώτερος ελληνισμός από το 1913 ως το 1941 (in Greek). Ekdotiki Athinon. pp. 411–453.

- Knox, MacGregor, ‘Fascist Italy Assesses its Enemies, 1935–1940’, in Ernest R. May (ed.), Knowing One’s Enemies. Intelligence Assessment before the Two World Wars, Princeton, 1983.

- —— Mussolini Unleashed 1939–1941. Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy’s Last War, paperback edn.. Cambridge, 1986.

- —— Common Destiny. Dictatorship, Foreign Policy, and War in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, Cambridge, 2000.

- —— Hitler’s Italian Allies. Royal Armed Forces, Fascist Regime, and the War of 1940–1943, Cambridge, 2000.

- La Campagna di Grecia, Italian official history (in Italian), 1980.

- Lamb, Richard (1998). Mussolini as Diplomat. London: John Murray Publishers. ISBN 0-88064-244-0

- Mack Smith, Denis, Mussolini as a Military Leader, Reading, 1974.

- —— Mussolini’s Roman Empire, London/New York, 1976.

- —— Mussolini, paperback edn., London, 1983.

- Mazower, Mark, Inside Hitler’s Greece. The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44, New Haven/London, 1993.

- Papagos, Alexandros (1949). The Battle of Greece 1940–1941 Athens: J.M. Scazikis "Alpha", editions. ASIN B0007J4DRU.

- Plowman, Jeffrey (2013). War in the Balkans : the battle for Greece and Crete 1940-1. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 9781781592489.

- Prasca, Sebastiano Visconti (1946). Io Ho Aggredito La Grecia, Rizzoli.

- Ian Allan Pubs. The Balkans and North Africa 1941–42 (Blitzkrieg Series #4).

- Richter, Heinz A. (1998). Greece in World War II (in Greek). transl from German by Kostas Sarropoulos. Athens: Govostis. ISBN 960-270-789-5.

- von Rintelen, Enno, Mussolini als Bundesgenosse. Erinnerungen des deutschen Militärattachés in Rom 1936–1943, Tübingen/Stuttgart, 1951.

- Rodogno, Davide (2006). Fascism's European Empire: Italian Occupation During the Second World War. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84515-1.

- Sadkovich, James J., ‘Understanding Defeat. Reappraising Italy’s Role in World War II’, Journal of Contemporary History, 24 (1989)

- —— ‘The Italo-Greek War in Context. Italian Priorities and Axis Diplomacy’, Journal of Contemporary History, 28 (1993).

- —— 'Italian Morale during the Italo-Greek War of 1940–1941', War and Society, Volume 12, Issue 1 (1 May 1994), pp. 97–123.

- Stockings, Craig; Hancock, Eleanor (2013). Swastika over the Acropolis: Re-interpreting the Nazi Invasion of Greece in World War II. BRILL. ISBN 9789004254596.

- Sullivan, Brian R., "Where One Man, and Only One Man, Led’. Italy’s Path from Non-Alignment to Non-Belligerency to War, 1937–1940’, in Neville Wylie (ed.), European Neutrals and Non-Belligerents during the Second World War, Cambridge, 2002.

- The Testament of Adolf Hitler. The Hitler–Bormann Documents, February–April 1945, ed. François Genoud, London, 1961.

- Verzijl, J.H.W. (1970). International Law in Historical Perspective. Brill Archive. p. 396.

- Walker, Ian W. (2003). Iron Hulls, Iron Hearts; Mussolini's Elite Armoured Divisions in North Africa. Ramsbury: The Crowood Press. ISBN 1-86126-646-4.

- Willingham, Matthew (2005). Perilous commitments : the battle for Greece and Crete : 1940-1941 (1. publ. in Great Britain. ed.). Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 9781862272361.

- Wylie, Neville (ed.), European Neutrals and Non-Belligerents during the Second World War, Cambridge, 2002

![]() Media related to Greco-Italian War at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Greco-Italian War at Wikimedia Commons

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||