Great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power influence, which may cause middle or small powers to consider the great powers' opinions before taking actions of their own. International relations theorists have posited that great power status can be characterized into power capabilities, spatial aspects, and status dimensions. Sometimes the status of great powers is formally recognized in conferences such as the Congress of Vienna[1][4][5] or an international structure such as the United Nations Security Council.[1][2][6] At the same time the status of great powers can be informally recognized in a forum such as the G7/G8.[7][8][9][10]

The term "great power" was first used to represent the most important powers in Europe during the post-Napoleonic era. The "Great Powers" constituted the "Concert of Europe" and claimed the right to joint enforcement of the postwar treaties.[11] The formalization of the division between small powers[12] and great powers came about with the signing of the Treaty of Chaumont in 1814. Since then, the international balance of power has shifted numerous times, most dramatically during World War I and World War II. While some nations are widely considered to be great powers, there is no definitive list of them. In literature, alternative terms for great power are often world power[13] or major power,[14] but these terms can also be interchangeable with superpower.[15]

Characteristics

There are no set or defined characteristics of a great power. These characteristics have often been treated as empirical, self-evident to the assessor.[16] However, this approach has the disadvantage of subjectivity. As a result, there have been attempts to derive some common criteria and to treat these as essential elements of great power status.

Early writings on the subject tended to judge states by the realist criterion, as expressed by the historian A. J. P. Taylor when he noted that "The test of a great power is the test of strength for war."[17] Later writers have expanded this test, attempting to define power in terms of overall military, economic, and political capacity.[18] Kenneth Waltz, the founder of the neorealist theory of international relations, uses a set of five criteria to determine great power: population and territory; resource endowment; economic capability; political stability and competence; and military strength. These expanded criteria can be divided into three heads: power capabilities, spatial aspects, and status.[5]

Power dimensions

As noted above, for many, power capabilities were the sole criterion. However, even under the more expansive tests, power retains a vital place.

This aspect has received mixed treatment, with some confusion as to the degree of power required. Writers have approached the concept of great power with differing conceptualizations of the world situation, from multi-polarity to overwhelming hegemony. In his essay, 'French Diplomacy in the Postwar Period', the French historian Jean-Baptiste Duroselle spoke of the concept of multi-polarity: "A Great power is one which is capable of preserving its own independence against any other single power."[19]

This differed from earlier writers, notably from Leopold von Ranke, who clearly had a different idea of the world situation. In his essay 'The Great Powers', written in 1833, von Ranke wrote: "If one could establish as a definition of a Great power that it must be able to maintain itself against all others, even when they are united, then Frederick has raised Prussia to that position."[20] These positions have been the subject of criticism.[5]

Spatial dimension

All states have a geographic scope of interests, actions, or projected power. This is a crucial factor in distinguishing a great power from a regional power; by definition the scope of a regional power is restricted to its region. It has been suggested that a great power should be possessed of actual influence throughout the scope of the prevailing international system. Arnold J. Toynbee, for example, observes that "Great power may be defined as a political force exerting an effect co-extensive with the widest range of the society in which it operates. The Great powers of 1914 were 'world-powers' because Western society had recently become 'world-wide'."[21]

Other suggestions have been made that a great power should have the capacity to engage in extra-regional affairs and that a great power ought to be possessed of extra-regional interests, two propositions which are often closely connected.[22]

Status dimension

Formal or informal acknowledgment of a nation's great-power status has also been a criterion for being a great power. As political scientist George Modelski notes, "The status of Great power is sometimes confused with the condition of being powerful, The office, as it is known, did in fact evolve from the role played by the great military states in earlier periods ... But the Great power system institutionalizes the position of the powerful state in a web of rights and obligations."[23]

This approach restricts analysis to the post-Congress of Vienna epoch; it being there that great powers were first formally recognized.[5] In the absence of such a formal act of recognition it has been suggested that great power status can arise by implication, by judging the nature of a state's relations with other great powers.[24]

A further option is to examine a state's willingness to act as a great power.[24] As a nation will seldom declare that it is acting as such, this usually entails a retrospective examination of state conduct. As a result this is of limited use in establishing the nature of contemporary powers, at least not without the exercise of subjective observation.

Other important criteria throughout history are that great powers should have enough influence to be included in discussions of political and diplomatic questions of the day, and have influence on the final outcome and resolution. Historically, when major political questions were addressed, several great powers met to discuss them. Before the era of groups like the United Nations, participants of such meetings were not officially named, but were decided based on their great power status. These were conferences which settled important questions based on major historical events. This might mean deciding the political resolution of various geographical and nationalist claims following a major conflict, or other contexts.

There are several historical conferences and treaties which display this pattern, such as the Congress of Vienna, the Congress of Berlin, the discussions of the Treaty of Versailles which redrew the map of Europe, and the Treaty of Westphalia.

History

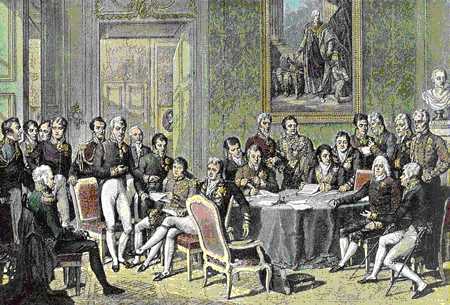

Different sets of great, or significant, powers have existed throughout history; however, the term "great power" has only been used in scholarly or diplomatic discourse since the Congress of Vienna in 1815.[4][5] The Congress established the Concert of Europe as an attempt to preserve peace after the years of Napoleonic Wars.

Lord Castlereagh, the British Foreign Secretary, first used the term in its diplomatic context, in a letter sent on February 13, 1814: "It affords me great satisfaction to acquaint you that there is every prospect of the Congress terminating with a general accord and Guarantee between the Great powers of Europe, with a determination to support the arrangement agreed upon, and to turn the general influence and if necessary the general arms against the Power that shall first attempt to disturb the Continental peace."[11]

The Congress of Vienna consisted of five main powers: the Austrian Empire, France, Prussia, Russia, and the United Kingdom. These five primary participants constituted the original great powers as we know the term today.[5] Other powers, such as Spain, Portugal, and Sweden were consulted on certain specific issues, but they were not full participants. Hanover, Bavaria, and Württemberg were also consulted on issues relating to Germany.

Of the five original great powers recognised at the Congress of Vienna, only France and the United Kingdom have maintained that status continuously to the present day, although France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War and occupied during World War II. After the Congress of Vienna, the British Empire emerged as the pre-eminent power, due to its navy and the extent of its territories, which signalled the beginning of the Pax Britannica and of the Great Game between Britain and Russia. The balance of power between the Great Powers became a major influence in European politics, prompting Otto von Bismarck to say "All politics reduces itself to this formula: try to be one of three, as long as the world is governed by the unstable equilibrium of five great powers."[25][26][27][28]

Over time, the relative power of these five nations fluctuated, which by the dawn of the 20th century had served to create an entirely different balance of power. Some, such as the United Kingdom and Prussia (as the founder of the newly formed German state), experienced continued economic growth and political power.[29] Others, such as Russia and Austria-Hungary, stagnated.[30] At the same time, other states were emerging and expanding in power, largely through the process of industrialization. The foremost of these emerging powers were Japan after the Meiji Restoration and the United States after its civil war, both of which had been minor powers in 1815. By the dawn of the 20th century, the balance of world power had changed substantially since the Congress of Vienna. The Eight-Nation Alliance was a belligerent alliance of eight nations against the Boxer Rebellion in China. It formed in 1900 and consisted of the five Congress powers plus Italy, Japan, and the United States, representing the great powers at the beginning of 20th century.[31]

Great powers at war

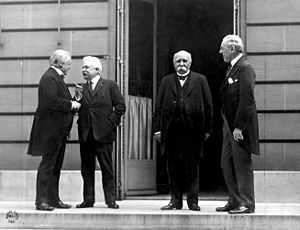

Shifts of international power have most notably occurred through major conflicts.[32] The conclusion of the Great War and the resulting treaties of Versailles, St-Germain, and Trianon witnessed the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Japan and the United States as the chief arbiters of the new world order.[33] In the aftermath of World War I the German Empire was defeated, the Austria-Hungarian empire was divided into new, less powerful states and the Russian Empire fell to a revolution. During the Treaty of Versailles the "Big Three"—France, United Kingdom and the United States—held noticeably more power and influence on the proceedings and outcome of the treaty than Italy or Japan.[34][35][36]

The victorious great powers also gained an acknowledgement of their status through permanent seats at the League of Nations Council, where they acted as a type of executive body directing the Assembly of the League. However, the Council began with only four permanent members—Great Britain, France, Italy, and Japan—because the United States, meant to be the fifth permanent member, left because the US Senate voted on 19 March 1920 against the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, thus preventing American participation in the League.

When World War II started in 1939, it divided the world into two alliances—the Allies (the United Kingdom and France at first in Europe, China in Asia since 1937, followed in 1941 by the Soviet Union, the United States); and the Axis powers consisting of Germany, Italy and Japan.[37][nb 1] The end of World War II saw the United States, United Kingdom, and Soviet Union emerge as the primary victors. The importance of the Republic of China and France was acknowledged by their inclusion, along with the other three, in the group of countries allotted permanent seats in the United Nations Security Council.

Since the end of the World Wars, the term "great power" has been joined by a number of other power classifications. Foremost among these is the concept of the superpower, used to describe those nations with overwhelming power and influence in the rest of the world. It was first coined in 1944 by William T.R. Fox[38] and according to him, there were three superpowers: the British Empire, the United States, and the Soviet Union. But by the mid-1950s the British Empire lost its superpower status, leaving the United States and the Soviet Union as the world's superpowers.[nb 2] The term middle power has emerged for those nations which exercise a degree of global influence, but are insufficient to be decisive on international affairs. Regional powers are those whose influence is generally confined to their region of the world.

During the Cold War, the Asian power of Japan and the European powers of the United Kingdom, France, and West Germany rebuilt their economies. France and the United Kingdom maintained technologically advanced armed forces with power projection capabilities and maintain large defence budgets to this day. Yet, as the Cold War continued, authorities began to question if France and the United Kingdom could retain their long-held statuses as great powers.[39] China, with the world's largest population, has slowly risen to great power status, with large growth in economic and military power in the post-war period. After 1949, the Republic of China began to lose its recognition as the sole legitimate government of China by the other great powers, in favour of the People's Republic of China. Subsequently, in 1971, it lost its permanent seat at the UN Security Council to the People's Republic of China.

Great powers at peace

According to Joshua Baron – a "researcher, lecturer, and consultant on international conflict" – since the early 1960s direct military conflicts and major confrontations have "receded into the background" with regards to relations among the great powers.[40] Baron argues several reasons why this is the case, citing the unprecedented rise of the United States and its predominant position as the key reason. Baron highlights that since World War Two no other great power has been able to achieve parity or near parity with the United States, with the exception of the Soviet Union for a brief time.[40] This position is unique among the great powers since the start of the modern era (the 16th century), where there has traditionally always been "tremendous parity among the great powers". This unique period of American primacy has been an important factor in maintaining a condition of peace between the great powers.[40]

Another important factor is the apparent consensus among Western great powers that military force is no longer an effective tool of resolving disputes among their peers.[40] This "subset" of great powers – France, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States – consider maintaining a "state of peace" as desirable. As evidence, Baron outlines that since the Cuban missile crisis (1962) during the Cold War, these influential Western nations have resolved all disputes among the great powers peacefully at the United Nations and other forums of international discussion.[40]

Referring to great power relations pre-1960, Joshua Baron highlights that starting from around the 16th century and the rise of several European great powers, military conflicts and confrontations was the defining characteristic of diplomacy and relations between such powers.[40] "Between 1500 and 1953, there were 64 wars in which at least one great power was opposed to another, and they averaged little more than five years in length. In approximately a 450-year time frame, on average at least two great powers were fighting one another in each and every year."[40] Even during the period of Pax Britannica (or "the British Peace") between 1815 and 1914, war and military confrontations among the great powers was still a frequent occurrence. In fact, Joshua Baron points out that in terms of militarized conflicts or confrontations Britain lead the way in this period with nineteen such instances against; Russia (8), France (5), Germany/Prussia (5) and Italy (1).[40]

In his 2014 publication Great Power Peace and American Primacy, Joshua Baron considers China, France, Russia, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States as the current great powers.[40]

Aftermath of the Cold War

China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States are often referred to as great powers by academics due to "their political and economic dominance of the global arena".[41] These five nations are the only states to have permanent seats with veto power on the UN Security Council. They are also the only recognized "Nuclear Weapons States" under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and maintain military expenditures which are among the largest in the world.[42] However, there is no unanimous agreement among authorities as to the current status of these powers or what precisely defines a great power. For example, sources have at times referred to China,[43] France,[44] Russia[45][46][47] and the United Kingdom[44] as middle powers.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, its UN Security Council permanent seat was transferred to the Russian Federation in 1991, as its successor state. The newly formed Russian Federation emerged on the level of a great power, leaving the United States as the only remaining global superpower[nb 3] (although some support a multipolar world view).

Many academics also consider Japan and Germany to be great powers too, though due to their large advanced economies (having the third and fourth largest economies respectively) rather than their strategic and hard power capabilities (I.e the lack of permanent seats and veto power on the UN Security Council or strategic military reach).[48][49][50][51][52] Germany has been a member together with the five permanent Security Council members in the P5+1 grouping of world powers. Like China, France, Russia and the United Kingdom; Germany and Japan have also been referred to as middle powers.[53][54][55][56][57][58][59]

In addition to those contemporary great powers mentioned above, Zbigniew Brzezinski[60] and Malik Mohan consider India to be a great power too.[61] Although unlike the contemporary great powers who have long been considered so, India's recognition among authorities as a great power is comparatively recent.[61] However there is no collective agreement among observers as to the status of India, for example, a number of academics believe that India is still emerging as a great power,[62] while some believe that India is a middle power.[63]

Emerging powers

With continuing European integration, the European Union is increasingly being seen as a great power in its own right,[64] with representation at the WTO and at G8 and G-20 summits. This is most notable in areas where the European Union has exclusive competence (i.e. economic affairs). It also reflects a non-traditional conception of Europe's world role as a global "civilian power", exercising collective influence in the functional spheres of trade and diplomacy, as an alternative to military dominance.[65] The European Union is a supranational union and not a sovereign state, and has limited scope in the areas of foreign affairs and defence policy. These remain largely with the member states of the European Union, which include the three great powers of France, Germany and the United Kingdom (referred to as the "EU three").[66]

Brazil and India are widely regarded as emerging powers with the potential to be great powers.[1] Political scientist Stephen P. Cohen asserts that India is an emerging power, but highlights that some strategists consider India to be already a great power.[67] Some academics such as Zbigniew Brzezinski and Dr David A. Robinson already regard India as a major or great power.[66][68]

Permanent membership of the UN Security Council is widely regarded as being a central tenet of great power status in the modern world; Brazil, Germany, India and Japan form the G4 nations which support one another (and have varying degrees of support from the existing permanent members) in becoming permanent members. There are however few signs that reform of the Security Council will happen in the near future.

Hierarchy of great powers

Acclaimed political scientist, geo-strategist, and former United States National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, appraised the current standing of the great powers in his 2012 publication Strategic Vision: America and the Crisis of Global Power. In relation to great powers, he makes the following points:

"The United States is still preeminent but the legitimacy, effectiveness, and durability of its leadership is increasingly questioned worldwide because of the complexity of its internal and external challenges. ... The European Union could compete to be the world's number two power, but this would require a more robust political union, with a common foreign policy and a shared defense capability. ... In contrast, China's remarkable economic momentum, its capacity for decisive political decisions motivated by clearheaded and self centered national interest, its relative freedom from debilitating external commitments, and its steadily increasing military potential coupled with the worldwide expectation that soon it will challenge America's premier global status justify ranking China just below the United States in the current international hierarchy. ... A sequential ranking of other major powers beyond the top two would be imprecise at best. Any list, however, has to include Russia, Japan, and India, as well as the EU's informal leaders: Great Britain, Germany, and France."[60]

List of great powers by date

See also

- List of pre-modern great powers

- Power in international relations

- Potential superpowers

Notes

- ↑ Even though the book The Economics of World War II lists seven great powers at the start of 1939 (the British Empire, the Empire of Japan, France, the Kingdom of Italy, Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union and the United States), it focuses only on six of them, because France surrendered shortly after the war began.

- ↑ The 1956 Suez Crisis suggested that the United Kingdom, financially weakened by two world wars, could not then pursue its foreign policy objectives on an equal footing with the new superpowers without sacrificing convertibility of its reserve currency as a central goal of policy. – from superpower cited by Klug, Adam; Smith, Gregor W. (1999). "Suez and Sterling, 1956". Explorations in Economic History 36 (3): 181–203. doi:10.1006/exeh.1999.0720.

- ↑ The fall of the Berlin Wall and the breakup of the Soviet Union left the United States as the only remaining superpower in the 1990s.

- ↑ After the Statute of Westminster came into effect in 1931, the United Kingdom no longer represented the British Empire in world affairs.

- ↑ "the prime minister of Canada (during the Treaty of Versailles) said that there were 'only three major powers left in the world the United States, Britain and Japan' ... (but) The Great Powers could not be consistent. At the instance of Britain, Japan's ally, they gave Japan five delegates to the Peace Conference, just like themselves, but in the Supreme Council the Japanese were generally ignored or treated as something of a joke." from MacMillan, Margaret (2003). Paris 1919. United States of America: Random House Trade. p. 306. ISBN 0-375-76052-0.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 Peter Howard (2008). "Great Powers". Encarta. MSN. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 Louden, Robert (2007). "Great+power" The world we want. United States of America: Oxford University Press US. p. 187. ISBN 0195321375.

- ↑ Kelsen, Hans (2000). The Law of the United Nations: A Critical Analysis of Its Fundamental Problems. United States of America: The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. pp. 272–281, 911. ISBN 1-58477-077-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Fueter, Eduard (1922). World history, 1815–1930. United States of America: Harcourt, Brace and Company. pp. 25–28, 36–44. ISBN 1-58477-077-5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 5.10 Danilovic, Vesna. "When the Stakes Are High—Deterrence and Conflict among Major Powers", University of Michigan Press (2002), pp 27, 225–228 (PDF chapter downloads) (PDF copy).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 T. V. Paul, James J. Wirtz, Michel Fortmann (2005). "Great+power" Balance of Power. United States of America: State University of New York Press, 2005. pp. 59, 282. ISBN 0791464016. Accordingly, the great powers after the Cold War are Britain, China, France, Germany, Japan, Russia, and the United States p.59

- ↑ The Seven-Power Summit as an International Concert

- ↑ The G6/G7: great power governance

- ↑ The role of the G8 in International Peace and security

- ↑ Tables of Science Po and Documentation Francaise: Russia y las grandes potencias and G8 et Chine

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Charles Webster, (ed), British Diplomacy 1813–1815: Selected Documents Dealing with the Reconciliation of Europe, (1931), p307.

- ↑ Toje, A. (2010). The European Union as a small power: After the post-Cold War. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ↑ Dictionary - World power

- ↑ Dictionary - Major power

- ↑ Thesaurus - World Power

- ↑ Waltz, Kenneth N (1979). Theory of International Politics. McGraw-Hill. p. 131. ISBN 0-201-08349-3.

- ↑ Taylor, Alan JP (1954). The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918. Oxford: Clarendon. p. xxiv. ISBN 0-19-881270-1.

- ↑ Organski, AFK – World Politics, Knopf (1958)

- ↑ contained on page 204 in: Kertesz and Fitsomons (eds) – Diplomacy in a Changing World, University of Notre Dame Press (1960)

- ↑ Iggers and von Moltke "In the Theory and Practice of History", Bobbs-Merril (1973)

- ↑ Toynbee, Arnold J (1926). The World After the Peace Conference. Humphrey Milford and Oxford University Press. p. 4.

- ↑ Stoll, Richard J – State Power, World Views, and the Major Powers, Contained in: Stoll and Ward (eds) – Power in World Politics, Lynne Rienner (1989)

- ↑ Modelski, George (1972). Principles of World Politics. Free Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-02-921440-4.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Domke, William K – Power, Political Capacity, and Security in the Global System, Contained in: Stoll and Ward (eds) – Power in World Politics, Lynn Rienner (1989)

- ↑ Bartlett, C. J. (1996-10-15). Peace, War and the European Powers, 1814–1914. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 106. ISBN 9780312161385. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ Cassels, Alan (1996). Ideology and International Relations in the Modern World. Psychology Press. p. 86. ISBN 9780415119269. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ "The Transformation of European Politics, 1763–1848". Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- ↑ Britain And Germany: from Ally to Enemy

- ↑ "Multi-polarity vs Bipolarity, Subsidiary hypotheses, Balance of Power" (PPT). University of Rochester. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ↑ Tonge, Stephen. "European History Austria-Hungary 1870–1914". Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31.6 31.7 31.8 Dallin, David (2006-11-30). The Rise of Russia in Asia. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-2919-1.

- ↑ Power Transitions as the cause of war.

- ↑ Globalization and Autonomy by Julie Sunday, McMaster University.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 34.5 MacMillan, Margaret (2003). Paris 1919. United States of America: Random House Trade. pp. 36, 306, 431. ISBN 0-375-76052-0.

- ↑ Boemeke, Manfred; Gerald D. Feldman; Elisabeth Glaser-Schmidt (1998). The Treaty of Versailles: 75 Years After. United States of America: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62132-1.

- ↑ Paris 1919 by Margaret MacMillan has the Council of Five (Britain, France, Italy, Japan and the United States) as the main victors and remaining Great Powers.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 37.5 37.6 37.7 Harrison, M (2000) The Economics of World War II: Six Great Powers in International Comparison, Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 The Superpowers: The United States, Britain and the Soviet Union – Their Responsibility for Peace (1944), written by William T.R. Fox

- ↑ Holmes, John. "Middle Power". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 40.6 40.7 40.8 40.9 40.10 40.11 40.12 40.13 40.14 40.15 40.16 Baron, Joshua (22 January 2014). Great Power Peace and American Primacy: The Origins and Future of a New International Order. United States: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1137299487.

- ↑ Yasmi Adriansyah, 'Questioning Indonesia's place in the world', Asia Times (20 September 2011): 'Though there are still debates on which countries belong to which category, there is a common understanding that the GP [great power] countries are the United States, China, United Kingdom, France and Russia. Besides their political and economic dominance of the global arena, these countries have special status in the United Nations Security Council with their permanent seats and veto rights.'

- ↑ "The 15 countries with the highest military expenditure in 2012 (table)" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Gerald Segal, Does China Matter?, Foreign Affairs (September/October 1999).

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 according to P. Shearman, M. Sussex, European Security After 9/11, Ashgate, 2004, both UK and France were global powers now reduced to middle-power status.

- ↑ Neumann, Iver B. (2008). "Russia as a great power, 1815–2007". Journal of International Relations and Development 11: 128–151 [p. 128]. doi:10.1057/jird.2008.7.

As long as Russia's rationality of government deviates from present-day hegemonic neo-liberal models by favouring direct state rule rather than indirect governance, the West will not recognize Russia as a fully fledged great power.

- ↑ Garnett, Sherman (6 November 1995). "Russia ponders its nuclear options". Washington Times. p. 2.

Russia must deal with the rise of other middle powers in Eurasia at a time when it is more of a middle power itself.

- ↑ Kitney, Geoff (25 March 2000). "Putin It To The People". Sydney Morning Herald. p. 41.

The Council for Foreign and Defence Policy, which includes senior figures believed to be close to Putin, will soon publish a report saying Russia's superpower days are finished and that the country should settle for being a middle power with a matching defence structure.

- ↑ T.V. Paul; James Wirtz; Michel Fortmann (8 September 2004). Balance of Power: Theory and Practice in the 21st Century. Stanford University Press. pp. 59–. ISBN 978-0-8047-5017-2. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ↑ Great Powers

- ↑ Asia’s Overlooked Great Power, APR 18, 2007

- ↑ Worldcrunch.com (2011-11-28). "Europe's Superpower: Germany Is The New Indispensable (And Resented) Nation - All News Is Global". Worldcrunch.com. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ↑ Winder, Simon (2011-11-19). "Germany: The reluctant superpower". The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ Sperling, James (2001). "Neither Hegemony nor Dominance: Reconsidering German Power in Post Cold-War Europe". British Journal of Political Science 31 (2). doi:10.1017/S0007123401000151.

- ↑ Max Otte, Jürgen Greve (2000). A Rising Middle Power?: German Foreign Policy in Transformation, 1989–1999. Germany. p. 324. ISBN 0-312-22653-5.

- ↑ Er LP (2006) Japan's Human Security Rolein Southeast Asia

- ↑ "Merkel as a world star - Germany's place in the world", The Economist (November 18, 2006), p. 27: "Germany, says Volker Perthes, director of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, is now pretty much where it belongs: squarely at the centre. Whether it wants to be or not, the country is a Mittelmacht, or middle power."

- ↑ Susanna Vogt, "Germany and the G20", in Wilhelm Hofmeister, Susanna Vogt, G20: Perceptions and Perspectives for Global Governance (Singapore: Oct. 19, 2011), p. 76, citing Thomas Fues and Julia Leininger (2008): "Germany and the Heiligendamm Process", in Andrew Cooper and Agata Antkiewicz (eds.): Emerging Powers in Global Governance: Lessons from the Heiligendamm Process, Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, p. 246: "Germany’s motivation for the initiative had been '... driven by a combination of leadership qualities and national interests of a middle power with civilian characteristics'."

- ↑ "Change of Great Powers", in Global Encyclopaedia of Political Geography, by M.A. Chaudhary and Guatam Chaudhary (New Delhi, 2009.), p. 101: "Germany is considered by experts to be an economic power. It is considered as a middle power in Europe by Chancellor Angela Merkel, former President Johannes Rau and leading media of the country."

- ↑ Susanne Gratius, Is Germany still a EU-ropean power?, FRIDE Policy Brief, No. 115 (February 2012), pp. 1, 2: "Being the world's fourth largest economic power and the second largest in terms of exports has not led to any greater effort to correct Germany's low profile in foreign policy ... For historic reasons and because of its size, Germany has played a middle-power role in Europe for over 50 years."

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Strategic Vision: America & the Crisis of Global Power by Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski, pp 43–45. Published 2012.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Malik, Mohan (2011). China and India: Great Power Rivals. United States: FirstForumPress. ISBN 1935049410.

- ↑ Brewster, David (2012). India as an Asia Pacific Power. United States: Routledge. ISBN 1136620087.

- ↑ Charalampos Efstathopoulosa, 'Reinterpreting India's Rise through the Middle Power Prism', Asian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 19, Issue 1 (2011), p. 75: 'India's role in the contemporary world order can be optimally asserted by the middle power concept. The concept allows for distinguishing both strengths and weakness of India's globalist agency, shifting the analytical focus beyond material-statistical calculations to theorise behavioural, normative and ideational parameters.'

- ↑ Buzan, Barry (2004). The United States and the Great Powers. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity Press. p. 70. ISBN 0-7456-3375-7.

- ↑ Veit Bachmann and James D Sidaway, "Zivilmacht Europa: A Critical Geopolitics of the European Union as a Global Power", Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Jan., 2009), pp. 94–109.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Strategic Vision: America & the Crisis of Global Power by Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski, pp 43–45. Published 2012.

- ↑ "India: Emerging Power", by Stephen P. Cohen, p. 60

- ↑ "India’s Rise as a Great Power, Part One: Regional and Global Implications". Futuredirections.org.au. 7 July 2011. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 69.3 69.4 McCarthy, Justin (1880). A History of Our Own Times, from 1880 to the Diamond Jubilee. New York, United States of America: Harper & Brothers, Publishers. pp. 475–476.

- ↑ McCourt, David (28 May 2014). Britain and World Power Since 1945: Constructing a Nation's Role in International Politics. United States of America: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472072218.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 UW Press: Korea's Future and the Great Powers

- ↑ Yong Deng and Thomas G. Moore (2004) "China Views Globalization: Toward a New Great-Power Politics?" The Washington Quarterly

- ↑ Friedman, George (2008-06-15). "The Geopolitics of China" (PDF). Stratfor. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2009. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ↑ Kennedy, Paul (1987). The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. United States of America: Random House. p. 204. ISBN 0-394-54674-1.

- ↑ Best, Antony; Hanhimäki, Jussi; Maiolo, Joseph; Schulze, Kirsten (2008). International History of the Twentieth Century and Beyond. United States of America: Routledge. p. 9. ISBN 0415438969.

- ↑ Wight, Martin (2002). Power Politics. United Kingdom: Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 46. ISBN 0826461743.

- ↑ Waltz, Kenneth (1979). Theory of International Politics. United States of America: McGraw-Hill. p. 162. ISBN 0-07-554852-6.

- ↑ Richard N. Haass, "Asia’s overlooked Great Power", Project Syndicate April 20, 2007.

- ↑ "Analyzing American Power in the Post-Cold War Era". Retrieved 2007-02-28.

Further reading

- Mearsheimer, John J. (2001). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: Norton. ISBN 0393020258.

- Waltz, Kenneth N. (1979). Theory of International Politics. Reading: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0201083493.

- Witkopf, Eugene R. (1981). World Politics: Trend and Transformation. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312892462.

- Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste. France and the Nazi Threat: The Collapse of French Diplomacy 1932–1939. Enigma Books. ISBN 1-929631-15-4.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||