Great chain of being

The great chain of being (Latin: scala naturae, literally "ladder/stair-way of nature"), is a concept derived from Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, and Proclus; further developed during the Middle Ages, it reached full expression in early modern Neoplatonism.[1][2] It details a strict, religious hierarchical structure of all matter and life, believed to have been decreed by God. The chain starts from God and progresses downward to angels, demons (fallen/renegade angels), stars, moon, kings, princes, nobles, men, wild animals, domesticated animals, trees, other plants, precious stones, precious metals, and other minerals.[3]

Divisions

The Chain of Being is composed of a great number of hierarchical links, from the most basic and foundational elements up through the very highest perfection, in other words, God.[4]

God, and beneath him, the angels, both existing wholy in spirit form, sit at the top of the chain. Earthly flesh is fallible and ever-changing: mutable. Spirit, however, is unchanging and permanent. This sense of permanence is crucial to understanding this conception of reality. It is generally impossible to change the position of an object in the hierarchy. (One exception might be in the realm of alchemy, where alchemists attempted to transmute base elements, such as lead, into higher elements, either silver, or, more often, gold—- the highest element.)[3]

In the natural order, earth (rock) is at the bottom of the chain: this element possesses only the attribute of existence. Each link succeeding upward contains the positive attributes of the previous link and adds (at least) one other. Rocks, as above, possess only existence; the next link up, plants, possess life and existence. Animals add not only motion, but appetite as well.[3]

Man is both mortal flesh, as those below him, and also spirit as those above. In this dichotomy, the struggle between flesh and spirit becomes a moral one. The way of the spirit is higher, more noble; it brings one closer to God. The desires of the flesh move one away from God. The Christian fall of Lucifer is thought of as especially terrible, as angels are wholly spirit, yet Lucifer defied God, the ultimate perfection.[3]

Subdivisions

Each link in the chain might be divided further into its component parts. In medieval secular society, for example, the king is at the top, succeeded by the aristocratic lords, and then the peasants below them. Solidifying the king's position at the top of humanity's social order is the doctrine of the Divine Right of Kings. In the family, the father is head of the household; below him, his wife; below her, their children.

Just as Milton's Paradise Lost ranked the angels (c.f. Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite's ranking of angels), so too does Christian culture conceive of angels in orders of archangels, seraphim, and cherubim, among others.

Amongst animals, subdivisions are equally apparent. At the top of the animals are wild beasts (such as lions), which were seen as superior as they defied training and domestication. Below them are domestic animals, further sub-divided so that useful animals (such as dogs and horses) are higher than docile creatures, such as sheep. Birds are also sub-divided, with eagles above pigeons, for example. Fish come below birds and are sub-divided between actual fish and other sea creatures. Below them come insects, with useful insects such as spiders and bees and attractive creatures such as ladybirds and dragonflies at the top, and unpleasant insects such as flies and beetles at the bottom. At the very bottom of the animal sector are snakes, which are relegated to this position as punishment for the serpent's actions in the Garden of Eden.

Below animals comes the division for plants, which is further sub-divided. Trees are at the top, with useful trees such as oaks at the top, and the traditionally demonic yew tree at the bottom. Food-producing plants such as cereals and vegetables are further sub-divided.

At the very bottom of the chain are minerals. At the top of this section are metals (further sub-divided, with gold at the top and lead at the bottom), followed by rocks (with granite and marble at the top), soil (sub-divided between nutrient-rich soil and low-quality types), sand, grit, dust, and, at the very bottom of the entire great chain, dirt.

The central concept of the chain of being is that everything imaginable fits into it somewhere, giving order and meaning to the universe.[3]

The Great Chain of Being

God

The top of the Chain of Being, also external to creation, God was believed to exist outside the physical limitations of time and space. He possessed the spiritual attributes of reason, love, and imagination, like all spiritual beings, but he alone possessed the divine attributes of omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence. God serves as the model of authority for the strongest, most virtuous, most excellent type of being within a specific category.

Angelic beings

Beings of pure spirit, angels had no physical bodies of their own. In order to affect the physical world, angels were thought to build temporary bodies for themselves out of particles of air. Medieval and Renaissance theologians believed angels to possess reason, love, imagination, and—like God—to stand outside the physical limitations of time. They possessed sensory awareness unbound by physical organs, and they possessed language. They lacked, however, the divine attributes of omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence of God, and they simultaneously lacked the physical passions experienced by humans and animals. Depending upon the author, the class of angels was further subdivided into three, seven, nine, or ten ranks, variously known as triads, orders or choirs. Each rank had greater power and responsibility than the entities below them. The most common classification is that of St. Thomas Aquinas.[5]

- Seraphim (seraph is the primate, or superior type of angel)

- Cherubim

- Thrones (ophanim)

- Dominations

- Virtues

- Powers

- Principalities

- Archangels

- Angels

Humanity

For Medieval and Renaissance thinkers, humans occupied a unique position on the Chain of Being, straddling the world of spiritual beings and the world of physical creation. Humans were thought to possess divine powers such as reason, love, and imagination. Like angels, humans were spiritual beings, but unlike angels, human souls were "knotted" to a physical body. As such, they were subject to passions and physical sensations—pain, hunger, thirst, sexual desire—just like other animals lower on the Chain of the Being. They also possessed the powers of reproduction unlike the minerals and rocks lowest on the Chain of Being. Humans had a particularly difficult position, balancing the divine and the animalistic parts of their nature. For instance, an angel is only capable of intellectual sin such as pride (as evidenced by Lucifer's fall from heaven in Christian belief). Humans, however, were capable of both intellectual sin and physical sins such as lust and gluttony if they let their animal appetites overrule their divine reason. Humans also possessed sensory attributes: sight, touch, taste, hearing, and smell. Unlike angels, however, their sensory attributes were limited by physical organs. (They could only know things they could discern through the five senses.) The highest-ranking human being was the King.

Animals

Animals, like humans higher on the Chain, were animated (capable of independent motion). They possessed physical appetites and sensory attributes, the number depending upon their position within the Chain of Being. They had limited intelligence and awareness of their surroundings. Unlike humans, they were thought to lack spiritual and mental attributes such as immortal souls and the ability to use logic and language. The primate of all animals (the "King of Beasts") was variously thought to be either the lion or the elephant. However, each subgroup of animals also had its own primate, an avatar superior in qualities of its type.

- Avian Primate: Eagle

Note that avian creatures, linked to the element of air, were considered superior to aquatic creatures linked to the element of water. Air naturally tended to rise and soar above the surface of water, and analogously, aerial creatures were placed higher in the Chain.

The chart would continue to descend through various reptiles, amphibians, and insects. The higher up the chart one went, the more noble, mobile, strong, and intelligent the creature in Renaissance belief. At the very bottom of the animal section, we find sessile creatures like the oysters, clams, and barnacles. Like the plants below them, these creatures lacked mobility, and were thought to lack various sensory organs such as sight and hearing. However, they were still considered superior to plants because they had tactile and gustatory senses (touch and taste).

Plants

Plants, like other living creatures, possessed the ability to grow in size and reproduce. However, they lacked mental attributes and possessed no sensory organs. Instead, their gifts included the ability to eat soil, air, and "heat." (Photosynthesis was a poorly understood phenomenon in medieval and Renaissance times.) Plants did have greater tolerances for heat and cold, and immunity to the pain that afflicts most animals. At the very bottom of the botanical hierarchy, the fungus and moss, lacking leaf and blossom, were so limited in form that Renaissance thinkers thought them scarcely above the level of minerals. However, each plant was also thought to be gifted with various edible or medicinal virtues unique to its own type.

- Trees, with the primate: the oak tree

- Shrubs

- Bushes

- "Crops" (corn, wheat, etc.)

- Herbs

- Ferns

- Weeds

- Moss

- Fungus

Minerals

Creations of the earth, the lowest of elements, all minerals lacked the plant's basic ability to grow and reproduce. They also lacked mental attributes and sensory organs found in beings higher on the Chain. Their unique gifts, however, were typically their unusual solidity and strength. Many minerals, in fact, were thought to possess magical powers, particularly gems. The Mineral primate is the Diamond.

- Minute Particles (gravel, sand, soil, etc.)

The Great Chain in natural science

From Aristotle to Linnaeus

.png)

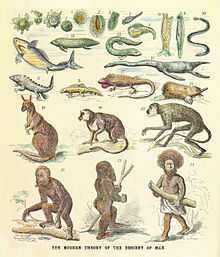

The basic idea of a ranking of the world's organisms goes back to Aristotle and his biological classification, where he ranked animals over plants based on their ability to move and sense, and graded the animals by their reproductive mode and possession of blood (he ranked all invertebrates as "bloodless"). British science historian Charles Singer pointed out: "Nothing is more remarkable than [Aristotle's] efforts to [exhibit] the relationships of living things as a scala naturae"[6] Aristotle's History of Animals classified organisms in relation to a linear "Ladder of Life", placing them according to complexity of structure and function so that higher organisms showed greater vitality and ability to move.

Aristotle's concept of higher and lower organisms was taken up by natural philosophers during the Scholastic period to form the basis of the Scala Naturae. The scala allowed for an ordering of beings, thus forming a basis for classification where each kind of mineral, plant and animal could be slotted into place. In medieval times, the Great Chain was seen as a God-given ordering: God at the top, dirt at the bottom, every grade of creature in its place. Just as rock never turns to flowers and worms never turn to lions, humans never turn to angels. This was not our lot in life. In the Northern Renaissance, the scientific focus shifted to biology.[7] The threefold division of the chain below humans formed the basis for Linnaeus's Systema Naturæ from 1737, where he divided the physical components of the world into the three familiar kingdoms of minerals, plants and animals.[8]

Scala naturae in evolution

The set nature of species, and thus the absoluteness of creatures' places in the Great Chain, came into question during the 18th century. The dual nature of the chain, divided yet united, had always allowed for seeing creation as essentially one continuous whole, with the potential for overlap between the links.[3] Radical thinkers like Jean-Baptiste Lamarck saw a progression of life forms from the simplest creatures striving towards complexity and perfection, a schema accepted by zoologists like Henri de Blainville.[9] The very idea of an ordering of organisms thus laid the basis for the idea of transmutation of species as formulated by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The idea of the Great Chain of Being continued to be part of the metaphysics in 19th century education, and the concept was well known. The geologist Charles Lyell used it as a metaphor in his 1851 Elements of Geology description of the geological column, where he used the term "missing links" in relation to missing parts of the continuum. The term "missing link" later came to signify transitional fossils, particularly those bridging the gulf between man and beasts.[10]

The idea of the Great Chain as well as the derived "missing link" was abandoned in early 20th century science, as the notion of modern animals representing ancestors of other modern animals was abandoned in modern biology. The idea of a certain sequence is valid so it lingers in practice, as entry level textbooks and courses in general biology teach plants before starting on animals, and go through the invertebrates before starting on vertebrates, typically finishing with mammals.

Adaptations and similar concepts

The American spiritual writer and philosopher Ken Wilber uses a concept called the "Great Nest of Being" which is similar to the Great Chain of Being, and which he claims to belong to a culture-independent "perennial philosophy" traceable across 3000 years of mystical and esoteric writings. Wilber's system corresponds with other concepts of transpersonal psychology.[11]

In the 1977 book "A Guide for the Perplexed", British philosopher and economist E. F. Schumacher wrote that fundamental gaps exist between the existence of minerals, plants, animals and humans, where each of the four classes of existence is marked by a level of existence not shared by that below. Clearly influenced by the Great Chain of Being, but lacking the angels and God, he called his hierarchy the "levels of being". In the book, he claims that science has generally avoided seriously discussing these discontinuities, because they present such difficulties for strictly materialistic science, and they largely remain mysteries.[12]

See also

- A Guide for the Perplexed - Levels of being

- History of biology

- Holon (philosophy)

- The Ladder of Divine Ascent

- Mandala

- Natural history

- Prosperity theology

- Plane (esotericism)

References

- ↑ "This idea of a great chain of being can be traced to Plato's division of the world into the Forms, which are full beings, and sensible things, which are imitations of the Forms and are both being and not being. Aristotle's teleology recognized a perfect being, and he also arranges all animals by a single natural scale according to the degree of perfection of their souls. The idea of the great chain of being was fully developed in Neoplatonism and in the Middle Ages.", Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy, p. 289 (2004)

- ↑ Edward P. Mahoney, "Lovejoy and the Hierarchy of Being", Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 48, No 2, pp. 211-230.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Arthur O. Lovejoy (1964) [1936], The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-36153-9

- ↑ Lovejoy, (1964). This theme permeates the book, but see e.g. p.59

- ↑ http://www.ccel.org/ccel/aquinas/summa.pdf

- ↑ Singer, Charles. A short history of biology. Oxford 1931.

- ↑ Allen Debus, Man and Nature in the Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978).

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin) (10th edition ed.). Stockholm: Laurentius Salvius.

- ↑ Appel, T.A. (1980). "Henri De Blainville and the Animal Series: A Nineteenth-Century Chain of Being". Journal of the History of Biology 13 (2): 291–319. doi:10.1007/BF00125745. JSTOR 4330767.

- ↑ "Why the term "missing links" is inappropriate". Hoxful Monsters. 10 June 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ↑ Freeman, Anthony (2006). "A Daniel Come to Judgement? Dennett and the Revisioning of Transpersonal Theory" (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies 13 (3): 95–109. Archived from the original on July 3, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- ↑ Pearce, Joseph (2008). "The Education of E.F. Schumacher". God Spy.

Further reading

- Arthur O. Lovejoy: The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press (1936)

- E. M. W. Tillyard: The Elizabethan World Picture (1942)

External links

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas – Chain of Being

- The Great Chain of Being reflected in the work of Descartes, Spinoza & Leibniz Peter Suber, Earlham College, Indiana