Grayanotoxin

Grayanotoxins are a group of closely related toxins found in rhododendrons and other plants of the family Ericaceae. They can be found in honey made from their nectar and cause a very rare poisonous reaction called grayanotoxin poisoning, honey intoxication, or rhododendron poisoning.[1] Grayanotoxin I (see below) is also known as andromedotoxin, acetylandromedol, rhodotoxin and asebotoxin; the systematic chemical name is: grayanotaxane-3,5,6,10,14,16-hexol 14-acetate.[2] It is named Leucothoe grayana, a plant species from Japan, which is in turn named after 19th century American botanist Asa Gray.[3]

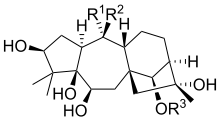

Chemical structure

| Grayanotoxin | R1 | R2 | R3 |

| Grayanotoxin I | OH | CH3 | Ac |

| Grayanotoxin II | CH2 | H | |

| Grayanotoxin III | OH | CH3 | H |

| Grayanotoxin IV | CH2 | Ac | |

Ac = acetyl

Grayanotoxins are polyhydroxylated cyclic diterpenes. They bind to specific sodium ion channels in cell membranes, the receptor sites involved in activation and inactivation.[4] The grayanotoxin prevents inactivation, leaving excitable cells depolarized.

Poisoning

Honey from Japan, Brazil, United States, Nepal, and British Columbia is most likely to be contaminated with grayanotoxins, although very rarely to toxic levels. However in the Caucasus region of Turkey, honey containing grayanotoxin known as deli bal or "mad honey" is deliberately produced,[5] and in the eighteenth century was exported to Europe where it may be added to alcoholic drinks for extra kick.[6][7] Historically the toxin in the honey was derived from the pollen and nectar of Rhododendron luteum and Rhododendron ponticum, which are found around the Black Sea. According to Pliny and later Strabo, the locals used the honey against the armies of Xenophon in 401 BCE and later against Pompey in 69 BCE.[8][7]

Gross physical symptoms occur after a dose-dependent latent period of minutes to three hours or so. Initial symptoms are excessive salivation, perspiration, vomiting, dizziness, weakness and paresthesia in the extremities and around the mouth, low blood pressure and sinus bradycardia. In higher doses symptoms can include loss of coordination, severe and progressive muscular weakness, electrocardiographic changes of bundle branch block and/or ST-segment elevations as seen in ischemic myocardial threat,[9] bradycardia (and, paradoxically, ventricular tachycardia), and nodal rhythm or Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Despite the potential cardiac problems the condition is rarely fatal and generally lasts less than a day. Medical intervention is not often needed but sometimes atropine therapy, vasopressors and other agents are used to mitigate symptoms.

In popular culture

The toxin from "hydrated rhododendron" is used in the 2009 film Sherlock Holmes to induce an "apparently mortal paralysis" in the movie's chief antagonist, Lord Blackwood, and Gladstone, Watson's bulldog.

In the 7/10/2013 episode of the USA Network show "Royal Pains", disk jockey "G" suffers from rhododendron honey poisoning and collapses with brachycardia due to a prank by his on-air partner, "Kiki".

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to grayanotoxins. |

- ↑ Demircan, A.; Keleş, A.; Bildik, F.; Aygencel, G.; Doğan, N. O.; Gómez, H. F. (2009). "Mad honey sex: Therapeutic misadventures from an ancient biological weapon". Annals of Emergency Medicine 54 (6): 824–829. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.06.010. PMID 19683834.

- ↑ The Merck Index (10th ed.). Rahway, NJ: Merck. 1983. pp. 652–653.

- ↑ Senning, Alexander (2007). Elsevier's Dictionary of Chemoetymology. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-444-52239-9.

- ↑ Ito, S.; Nakazato, Y.; Ohga, A. (1981). "Further evidence for the involvement of Na+ channels in the release of adrenal catecholamine: The effect of scorpion venom and grayanotoxin I". British Journal of Pharmacology 72 (1): 61–67. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb09105.x. PMC 2071538. PMID 6261866.

- ↑ Jamie Waters (1 October 2014). "The buzz about 'mad honey', hot honey and mead". The Guardian.

- ↑ Cheryll Williams (2010). Medicinal Plants in Australia Volume 1: Bush Pharmacy. Rosenberg Publishing. p. 223. ISBN 978-1877058790.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Adrienne Mayor. "Mad Honey!". Archaeology 46 (6): 32–40.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder on Mad Honey

- ↑ Sayin, M. R.; Karabag, T.; Dogan, S. M.; Akpinar, I.; Aydin, M. (2012). "Transient ST segment elevation and left bundle branch block caused by mad-honey poisoning". Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 124 (7–8): 278–281. doi:10.1007/s00508-012-0152-y. PMID 22527815.