Granville County, North Carolina

| Granville County, North Carolina | |

|---|---|

Granville County Courthouse | |

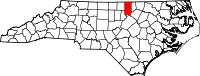

Location in the state of North Carolina | |

North Carolina's location in the U.S. | |

| Founded | 1746 |

| Named for | John Carteret, 2nd Earl Granville |

| Seat | Oxford |

| Largest city | Oxford |

| Area | |

| • Total | 536 sq mi (1,388 km2) |

| • Land | 532 sq mi (1,378 km2) |

| • Water | 4.9 sq mi (13 km2), 0.9% |

| Population | |

| • (2010) | 59,916 |

| • Density | 113/sq mi (44/km²) |

| Congressional districts | 1st, 6th, 13th |

| Website |

www |

Granville County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2010 census, the population was 59,916.[1] Its county seat is Oxford.[2]

Granville County comprises the Oxford, NC Micropolitan Statistical Area, which is also included in the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill, NC Combined Statistical Area.

The county includes access to Kerr Lake and Falls Lake and is included in the Roanoke, Tar and Neuse River water basins.

History

The county was formed in 1746 from Edgecombe County. It was named for John Carteret, 2nd Earl Granville,[3] who as heir to one of the eight original Lords Proprietors of the Province of Carolina, claimed one eighth of the land granted in the charter of 1665. The claim was established as consisting of approximately the northern half of North Carolina and this territory came to be known as the Granville District, also known as Oxford.

In 1752, parts of Granville County, Bladen County, and Johnston County were combined to form Orange County. In 1764, the eastern part of Granville County became Bute County. Finally, in 1881, parts of Granville County, Franklin County, and Warren County were combined to form Vance County.

John Penn (1741-1788) was an affluent politician of early America, as he was one of the three signers from North Carolina to sign the Declaration of Independence. After earning his admittance to the bar, Penn moved to Granville County in 1774. The county had become the hub of Carolina’s independence campaign. A remarkable orator, Penn had earned a place at the Third Provincial Congress of 1775, and he replaced Richard Caswell, joining William Hooper and Joseph Hewes in Philadelphia for the convening of the Continental Congress in 1776. Later, John Penn, with Cornelius Harnett and John Williams, signed the Articles of Confederation for North Carolina. Penn retired to Granville County, and he died at a relatively young age of 48 years old in 1788. His remains are interred at the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park in Greensboro, NC.

Like most early counties on the eastern side of the early North Carolina colony, Granville was site of the Tuscarora uprising. Once the natives were defeated after the Tuscarora War, Virginia farmers and their families settled Granville County and they focused on producing tobacco. Slave labor proved vital to the fledging economy of the region, and by the start of the Civil War, Granville plantation owners worked over 10,000 slaves on their farms.

During the Civil War, more than 2,000 men from Granville County served the Confederacy. One company was known as the “Granville Grays.” Most in this regiment fought in most major battles during the war. Surprisingly, many survived until the end of the war.

Although the Civil War brought an end to the plantation and slave labor economy that had made Granville County prosperous, the agricultural sector continued to thrive in the county due to the presence of free African Americans in Oxford and the discovery of bright leaf tobacco. Many African Americans in Granville County were free before the start of the Civil War, and they made lasting contributions to the region, particularly through their skilled labor. Several black masons constructed homes for the county’s wealthy landowners. Additionally, the bright leaf tobacco crop proved a successful agricultural product for Granville County. The sandy soil and a new tobacco crop could be “flue-dried” proved a great incentive to farmers and tobacco manufacturers. According to historian William S. Powell, Granville has remained a top tobacco-producing county in North Carolina for several decades. By the late 1800s and early 1900s, Oxford had become a thriving town with new industries, schools, literary institutions, and orphanages forming due to jobs created by the bright tobacco crop.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, northern Granville County, together with Halifax County, Virginia were important mining areas. Copper, tungsten, silver and gold were mined in the region. The Richmond to Danville Railroad was a critical lifeline to the northern part of the county and provided an important link for miners and farmers to get their goods to larger markets in Richmond and Washington, DC.

In the 1950s and 1960s, various manufacturing businesses had built up across Granville County, and the region gradually moved away from the agricultural sector. Today, the manufacturing industry produces cosmetics, tires, and clothing products in Granville County.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, Granville County played a pivotal role as tobacco supplier for the southeast United States. With many farms and contracts tied to major tobacco companies, like American Tobacco Company, Lorillard, Brown & Williamson, and Liggett Group, the local farmers became prosperous. With the Great Depression, came a plague new to the people of Granville County. The Granville Wilt Disease, as it became known, destroyed tobacco crops all across northern North Carolina. Botanists & Horticulturists found a cure for the famine at the Tobacco Research Center located in Oxford.

Camp Butner, opened in 1942 as a training camp for World War II soldiers, once encompassed over 40,000 acres in Granville, Person, and Durham counties. During the war, more than 30,000 soldiers were trained at Camp Butner, including the 35th and 89th Divisions. The hilly topography at Camp Butner proved helpful in teaching soldiers how to respond to gas bombings and how to use camouflage and cross rivers. Additionally, both German and Italian prisoners served as cooks and janitors at Camp Butner. Today, most of the land that was Camp Butner now belongs to the North Carolina government, and the no longer operational, Umstead Hospital was located at the Camp Butner site.

Granville County Courthouse

The Granville County Courthouse, of Greek Revival architect,[4] was built in 1840[5] and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 536 square miles (1,390 km2), of which 532 square miles (1,380 km2) is land and 4.9 square miles (13 km2) (0.9%) is water.[6]

Adjacent counties

- Halifax County, Virginia - north-northwest

- Mecklenburg County, Virginia - north

- Vance County - east

- Franklin County - southeast

- Wake County - south

- Durham County - southwest

- Person County - west

Major highways

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 10,982 | — | |

| 1800 | 14,015 | 27.6% | |

| 1810 | 15,576 | 11.1% | |

| 1820 | 18,222 | 17.0% | |

| 1830 | 19,355 | 6.2% | |

| 1840 | 18,817 | −2.8% | |

| 1850 | 21,249 | 12.9% | |

| 1860 | 23,396 | 10.1% | |

| 1870 | 24,831 | 6.1% | |

| 1880 | 31,286 | 26.0% | |

| 1890 | 24,484 | −21.7% | |

| 1900 | 23,263 | −5.0% | |

| 1910 | 25,102 | 7.9% | |

| 1920 | 26,846 | 6.9% | |

| 1930 | 28,723 | 7.0% | |

| 1940 | 29,344 | 2.2% | |

| 1950 | 31,793 | 8.3% | |

| 1960 | 33,110 | 4.1% | |

| 1970 | 32,762 | −1.1% | |

| 1980 | 34,043 | 3.9% | |

| 1990 | 38,345 | 12.6% | |

| 2000 | 48,498 | 26.5% | |

| 2010 | 59,916 | 23.5% | |

| Est. 2013 | 58,275 | −2.7% | |

As of the census of 2010,[11] there were 59,916 people in 20,628 households residing in the county. The population density was 111.6 people per square mile (43.1/km²). There were 22,827 housing units at an average density of 42.5 per square mile (16.4/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 60.4% White, 32.8% Black or African American, 0.6% Native American, 0.5% Asian, less than 0.1% Pacific Islander, 3.9% from other races, and 1.7% from two or more races. 7.5% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 20,628 households out of which 31.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them. The average household size was 2.90. In the county the population was spread out with 22.3% under the age of 18, 8.5% from 18 to 24, 12.0% from 25 to 34, 24.1% from 35 to 49, 20.7% from 50 to 64, and 12.40% who were 65 years of age or older. For every 100 females there were 114.7 males.

The median income[12] for a household in the county was $48,196, and the mean household income was $55,849. The median and mean income for a family was $56,493 and $64,311, respectively. The per capita income for the county was $21,201. About 7.6% of families and 11.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.4% of those under age 18 and 11.1% of those age 65 or over.

Law and government

Granville County is a member of the Kerr-Tar Regional Council of Governments.[13] Granville County is governed by a commissioner/manager form of government under the laws of the state of North Carolina. Granville County has seven commissioner electoral districts.

The Granville County Commissioners are David T. Smith (Chair), Zelodis Jay (Vice-Chair), R. David Currin, Jr., Tony W. Cozart, Ed Mims, Timothy Karan, and Edgar Smoak.

Education

The Granville County School System contains 2 charter schools, 4 high schools (with 2 subsidiary schools within schools), 4 middle schools, and 9 elementary schools.

- Charter Schools

- Oxford Preparatory School

- Falls Lake Academy

- High Schools

- J.F. Webb High School

- J.F. Webb School of Health and Life Sciences

- Granville Central High School

- Granville Early College High (affiliated with Vance-Granville Community College, which has a campus in Butner)

- South Granville High School

- South Granville School of Health and Life Sciences

- South Granville School of Integrated Technology and Leadership

- Middle Schools

- Butner-Stem Middle

- G.C. Hawley Middle

- Mary Potter Middle

- Northern Granville Middle

- Elementary Schools

- Butner-Stem Elementary

- C.G. Credle Elementary

- Creedmoor Elementary

- Joe Toler-Oak Hill Elementary

- Mt. Energy Elementary

- Stovall-Shaw Elementary

- Tar River Elementary

- West Oxford Elementary

- Wilton Elementary

Communities

Cities

Towns

Townships

- Brassfield

- Dutchville

- Fishing Creek

- Oak Hill

- Oxford

- Salem

- Sassafras Fork

- Tally Ho

- Walnut Grove

Unincorporated communities

- Berea

- Brassfield

- Bullock

- Culbreth

- Cozart

- Dexter

- Grassy Creek

- Grissom

- Lewis

- Northside

- Oak Hill

- Providence

- Shake Rag

- Shoofly

- Tally Ho

- Virgilina

- Wilbourns

- Wilton

Notable Residents

- John Penn- Signer of the Declaration of Independence (Stovall)

- James E. Webb- NASA Administrator (Tally Ho)

- Sam Ragan- Journalist (Berea)

- Richard H. Moore- politician, former NC State Treasurer (Oxford)

- Tiny Broadwick- First Female Parachutist (Oxford)

- Thad Stem, Jr.- Poet Laureate (Oxford)

- Franklin Wills Hancock, Jr.- U.S. Representative (Oxford)

- Benjamin Chavis- Civil Rights Leader (Oxford)

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 142.

- ↑ National Park Service (05-10-1979). "Granville Courthouse". Retrieved August 16, 2014. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Bowling, Lewis (2007). Granville County, North Carolina: Looking Back. The History Press. p. 26. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ United States Census 2010, US Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-11-15

- ↑ US Census FactFinder Retrieved 2011-11-15

- ↑ Kerr Tar Regional Council of Governments

External links

- Granville County government official website

- Granville County Chamber of Commerce

- Granville County Historical Society/Museums

- Vance-Granville Community College (located just on the Vance side of the Vance County-Granville County line)

- Northern Granville, Historic Oak Hill, Multi-Cultural Museum and Library

- The Granville Arts Council

|

Halifax County, Virginia | Mecklenburg County, Virginia | Mecklenburg County, Virginia |  |

| Person County | |

Vance County | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Durham County | Wake County | Franklin County |

| |||||||||||||||||||||