Gothicismus

.jpg)

Gothicismus, Gothism, or Gothicism (Swedish: Göticism) is the name given to what is considered to have been a cultural movement in Sweden, centered on the belief in the glory of the Swedish ancestors, originally considered to be the Geats, which were identified with the Goths. The founders of the movement were Nicolaus Ragvaldi and the brothers Johannes and Olaus Magnus. The belief continued to hold power in the 17th century, when Sweden was a great power following the Thirty Years' War, but lost most of its sway in the 18th. It was revitalized by national romanticism in the early 19th century, this time with the Vikings as heroic figures.

Origins

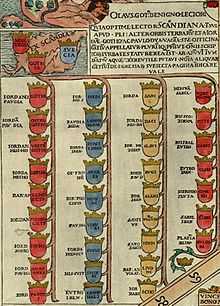

The name is derived from Jordanes's account of the Gothic urheimat in Scandinavia (Scandza), and the Gothicists in Sweden believed that the Goths had originated from Sweden. The Gothicismus movement took pride in the Gothic tradition that the Ostrogoths and their king Theodoric the Great, who assumed power in the Roman Empire, had Scandinavian ancestry. This pride was expressed as early as the medieval chronicles, where chroniclers wrote about the Goths as the ancestors of the Scandinavians, and the idea was used by Nicolaus Ragvaldi at the Council of Basel to argue that the Swedish monarchy was the foremost in Europe. It also permeated the writings of the Swedish writer Johannes Magnus (Historia de omnibus gothorum sueonumque regibus) and his brother Olaus Magnus (Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus). Both works had a strong influence on contemporary scholarship in Sweden.

Some scholars in Denmark attempted to identify the Goths with the Jutes; however, these ideas did not lead to the same widespread cultural movement in the Danish society as it did in the Swedish. In contrast with the Swedes, the Danes of this era did not forward claims to political legitimacy based on assertions that their country was the original homeland of the Goths or that the conquest of the Roman Empire was proof of their own country's military valour and power through history.[1]

During the 17th century, Danes and Swedes competed for the collection and publication of Icelandic manuscripts, Norse sagas, and the two Eddas. In Sweden, the Icelandic manuscripts became part of an origin myth and were seen as proof that the greatness and heroism of the old Geats had been passed down through the generations to the current population. This pride culminated in the publication of Olaus Rudbeck's Atland eller Manheim (1679–1702), in which he claimed that Sweden was identical to Atlantis.

Romantic nationalism

During the 18th century, the Swedish Gothicismus movement had sobered somewhat, but it revived during the Romantic nationalism from ca. 1800 and onwards, with Erik Gustaf Geijer and Esaias Tegnér in the Geatish society.

In Denmark, romantic nationalism led writers such as Johannes Ewald, N. F. S. Grundtvig (whose translation of Beowulf into Danish was the first into a modern language) and Adam Gottlob Oehlenschläger to take a renewed interest in Old Norse subjects. In other parts of Europe, the interest in Norse mythology, history and language was represented by Englishmen Thomas Gray, John Keats and William Wordsworth, and Germans Johann Gottfried Herder and Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock.

Architecture

In Scandinavian architecture, Gothicismus had its prime in the 1860s and 1870s, but it continued until ca 1900. The interest in Old Norse subjects led to the creation of a special architecture in wood inspired by the Stave churches, and it was in Norway that the style had its largest impact. The details that are often found in this style are dragon heads, and it is often called dragon style, false arcades, lathed colonnades, protruding lofts and a ridged roof.

References

- ↑ Sondrup, Steven P. and Virgil Nemoianu (2004). Nonfictional Romantic Prose: Expanding Borders. In the International Comparative Literature Association's History of Literatures in European Languages series. John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2004, ISBN 90-272-3451-5, p. 143.

Donecker, Stefan (2006), "There and Back Again: The North as Origin and Destination in Early Modern Migration Narratives", Images of the North, Reykjavik