Gospel of Jesus' Wife

The "Gospel of Jesus' Wife" is the name given to a papyrus fragment with a Coptic text that includes the words, "Jesus said to them, 'my wife...'".[1] The text was alleged to be a fourth-century Coptic translation of what is said to be "a gospel probably written in Greek in the second half of the second century."[2] The current consensus among scholars is that the fragment is a modern forgery.[3]

Professor Karen L. King (who announced the existence of the papyrus in 2012) and her colleague AnneMarie Luijendijk named the fragment the "Gospel of Jesus's Wife" for reference purposes[4] but have since acknowledged the name was controversial.[note 1] King has stated that the fragment, "should not be taken as proof that Jesus, the historical person, was actually married".[5] Luijendijk and fellow papyrologist Roger Bagnall authenticated the papyrus with Luijendijk suggesting it would have been impossible to forge.[5]

The Vatican's newspaper L'Osservatore Romano initially claimed the gospel was a "very modern forgery".[6] Some independent scholars subsequently suggested that the papyrus has textual mistakes (a typographical error) identical to those made only in a particular online modern iteration of corresponding texts.[7] Scholars debate whether that is either solely modern or unique.

Specifically, "Ariel Shisha-Halevy, Professor of Linguistics at Hebrew University and a leading expert on Coptic language, was asked to consider the text’s language. He concluded that the language itself offered no evidence of forgery. King also found examples from a new discovery in Egypt that has the same kind of grammar, showing that at least one unusual case is not unique. While some experts continue to disagree about the other case, King notes that newly discovered texts often have new spellings or grammatical oddities which add to our knowledge of the Coptic language." [8]

In April 2014, a careful analysis of the papyrus and the ink showed that the papyrus itself is ancient and dates to between the sixth and ninth centuries.[9][10][11][12] Scientists and scholars from the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, in New York, Princeton University, University of Arizona, Harvard University in conjunction with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Columbia University, MIT and more determined that "scientific testing provides no indication of modern fabrication ("forgery"), but does consistently offer positive evidence that the fragment as a material artifact is ancient."[13]

However, further analysis has suggested that the text includes additional errors that suggest it is not authentic.[14][15][16][17] In particular, Christian Askeland, a Coptic specialist at Indiana Wesleyan University, has claimed the fragment is, "a match for a papyrus fragment that is clearly a forgery". He suggests the text was written by the same person, in the same ink, with the same instrument as a similar fragment of the Gospel of John, belonging to the same anonymous owner and now overwhelmingly considered a fake.[14][17] Professor King said, "This is substantive, it’s worth taking seriously, and it may point in the direction of forgery. This is one option that should receive serious consideration, but I don’t think it’s a done deal."[15]

The previous ownership of the papyrus came into question, as an alleged previous owner, Hans-Ulrich Laukamp, was shown not to have owned it.[16]

Features

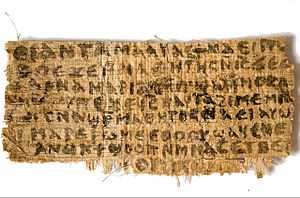

The fragment is rectangular, approximately 4 by 8 centimetres (1.6 in × 3.1 in). According to reports, "the fragment has eight incomplete lines of writing on one side and is badly damaged on the other side, with only three faded words and a few letters of ink that are visible, even with the use of infrared photography and computer-aided enhancement."[18]

King and Luijendijk suggested the text was written by Egyptian Christians before AD 400; it is in the language they believed was used by those people at that time. They considered that the papyrus fragment comes from a codex, rather than a scroll, as text appears on both sides.[18] However, Askeland has claimed that the fragment contains a "peculiar dialect of Coptic called Lycopolitan, which fell out of use during or before the sixth century". Test dated the papyrus itself to somewhere between the seventh and ninth centuries suggesting the writing is in a dialect that didn't exist when the papyrus was made.[14]

With reference to the speculative source of the text on the fragment, King and Luijendijk used the term "gospel" in a capacious sense which, as they wrote, includes, "all early Christian literature whose narrative or dialogue encompasses some aspect of Jesus's career (including post-resurrection appearances) or which was designated as 'gospel' already in antiquity."[2]

The English translation of the fragmentary lines is, for the recto:[2]

line 1: ... not [to] me. My mother gave me life ...

line 2: ... The disciples said to Jesus, ...

line 3: ... deny. Mary is (not?) worthy of it. ...

line 4: ... Jesus said to them, "My wife ...

line 5: ... she is able to be my disciple ...

line 6: ... Let wicked people swell up ...

line 7: ... As for me, I am with her in order to ...

line 8: ... an image ...

For the verso:

line 1: ... my moth[er] ...

line 2: ... three ...

line 3: ... ....

line 4: ... forth ...

lines 5 & 6: illegible ink traces

Provenance

Nothing has been published as to the provenance of the papyrus fragment before 1982, which happens to be the year before the Egyptian authorities passed a Law on the Protection of Antiquities[note 2] strictly regulating the ownership, possession, trade and removal from Egypt of antiquities.[19] As for events after 1982, it is reported that the fragment was acquired in 1997 by its current owner (who wishes to remain anonymous) as part of a cache of papyri and other documents said to have been purchased from a German-American collector who is said, in turn, to have acquired it in the 1960s in then-communist East Germany.[19]

Among the other documents in that cache were:- (a) a type-written letter dated 15 July 1982 addressed to one H. U. Laukamp from Prof. Dr. Peter Munro (Ägyptologisches Seminar, Freie Universität Berlin) which only mentions one of the papyri, reporting that a colleague, Prof. Fecht, had identified it as a 2nd-4th century AD fragment of the Gospel of John in Coptic, and giving recommendations as to its preservation; and (b) an undated and unsigned hand-written note in German and seemingly referring to the Gospel of Jesus' Wife fragment, which reported that "Professor Fecht" believed it is the only instance of a text in which Jesus uses direct speech to refer to a wife. This Professor Fecht is taken to be Gerhard Fecht who was on the faculty of Egyptology at the Free University of Berlin, at all relevant times. Laukamp died in 2001, Fecht in 2006 and Munro in 2009.

Publication

The existence of the papyrus fragment was announced at the International Congress of Coptic Studies in Rome on 18 September 2012 by Karen L. King, Hollis Professor of Divinity at Harvard Divinity School.[20][21] Scholarly publication of the text with commentary was slated for The Harvard Theological Review in January 2013[5] but on January 3, King and Kathyrn Dodgson (director of communications for Harvard Divinity School) confirmed to CNN that publication was being delayed pending the results of (in Dodgson's words) "further testing and analysis of the fragment, including testing by independent laboratories with the resources and specific expertise necessary to produce and interpret reliable results."[22] A revised version of the article appeared in the Harvard Theological Review in April 2014, together with several scientific reports on the testing of the papyrus.[23]

Two papyrologists, Roger Bagnall of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University and AnneMarie Luijendijk, an associate professor of religion at Princeton University, reviewed the fragment and determined it was likely authentic. According to Luijendijk, it would have been impossible to forge.[5]

Response

King told the International Congress of Coptic Studies that the text does not prove that Jesus had a wife. She noted that even as a translation of a 2nd-century AD Greek text, it would still have been written more than 100 years after the death of Jesus. According to King, the earliest and most reliable information about Jesus is silent on the question of his marital status.[24] King also acknowledged, though, that the text (which she suggested is a fragment from a non-canonical gospel) "provide[s] the first evidence that some early Christians believed Jesus had been married."[25] A Harvard News Office article reported that King dated the speculative Greek original to the second half of the second century because it shows close connections to other newly discovered gospels written at that time, especially the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Mary, and the Gospel of Philip.[26]

King later, in a 2012 documentary, commented on the possible implication of the papyrus fragment:

The question on many people's minds is whether this fragment should lead us to re-think whether Jesus was married. I think however, what it leads us to do, is not to answer that question one way or the other, it should lead us to re-think how Christianity understood sexuality and marriage in a very positive way, and to recapture the pleasures of sexuality, the joyfulness and the beauties of human intimate relations.[27]

Ben Witherington, Professor of New Testament Interpretation at the Asbury Theological Seminary, said that while the text might contribute to the study of Gnosticism in the 2nd or 4th century, it should not be considered a "game-changer" for those studying Jesus in a 1st-century historical context. He further explained that, "during the rise of the monastic movement, you had quite a lot of monk-type folks and evangelists who travelled in the company of a sister-wife" and that the term "wife" was open to interpretation.[28]

Father Henry Wansbrough echoed the same sentiments:

It will not have a great deal of importance for the Christian church. It will show that there was a group who had these beliefs in the second century - Christians or semi-Christians - who perhaps had not reflected enough on the implications of the canonical scriptures - to see that Jesus could not have been married. It's a historical interest, rather than a faith interest.[27]

Daniel B. Wallace, of the Dallas Theological Seminary, and others have suggested that the fragment appears to have been intentionally cut, most likely in modern times. They further suggest that this leads to the possibility that in context Jesus' may not have even been speaking of a literal wife.[29]

Authenticity

Since the presentation of the fragment, a number of scholars questioned its authenticity. Craig A. Evans of the Acadia Divinity College, suggested the "oddly written letters" were "probably modern". Others said the handwriting, grammar, shape of the papyrus, and the ink's colour and quality made it suspect.[30] Professor Francis Watson of Durham University published a paper on the papyrus fragment suggesting the text was a "patchwork of texts" from the "genuine" Gospel of Thomas which had been "copied and reassembled out of order".[31]

Andrew Bernhard discussed in an online paper that by using excerpts from a genuinely ancient text, a modern forger could have composed a text fragment that appeared authentically ancient even to highly reputable and capable scholars. He mentions after comparing Mike Grondin's Interlinear of the Gospel of Thomas, that there is resemblance between the Interlinear and the fragment:

Given the extraordinary similarities between the two different texts, it seems highly probable that Gos. Jes. Wife is indeed a "patchwork" of Gos. Thom. Most likely, it was composed after 1997 when Grondin’s Interlinear was first posted online.[32]

In September 2012, numerous news services announced that the Vatican's newspaper, L'Osservatore Romano, had declared the fragment counterfeit. As of 29 September 2012, all that L'Osservatore's search engine identified on the subject was part of an article dated 28 September 2012 by Professor Alberto Camplani of La Sapienza University in Rome[note 3] protesting against "the excessively direct link between research and journalism [which] had already occurred before the conference". He remarked that while the reports in the news media were marked by tones quick to shock, the papyrus had not been excavated from an archaeological site but had been acquired in the antiquities market, and he therefore urged that "numerous precautions be taken to ... exclude the possibility of forgery".[33] A brief editorial comment appended to the article by the editor of L'Osservatore Romano, Giovanni Maria Vian, dismissed the fragment as in ogni caso un falso ("in any case, a fake").[6] However, in a 2012 documentary focused on the fragment, Camplani suggested his position had changed and that he now considered it more likely to be authentic.[27]

A radiocarbon dating analysis of the papyrus by the Arizona Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory in 2013 found a date of 404 to 209 BC. However, the cleaning protocol had to be interrupted during processing to preserve the fragment. A second analysis was performed by Harvard University and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution found a mean date of 741 CE.[34] A Raman spectroscopy analysis at Columbia University found that the ink was consistent with those in manuscripts from 400 BC to AD 700–800. These analyses suggest that the fragment as a material artifact is probably ancient.[35] That date conflicts with Askeland's analysis of the language used in the text which he suggests is in a dialect which fell out of favour well before 741CE. He concluded that the text was written in a language that didn't exist when the fragment was created and that the text must have been written on a genuinely ancient fragment of papyrus by a modern forger.[14] In addition, Askeland's study indicates that an alleged fragment of the Gospel of John, provided from the same source as that which provided the Gospel of Jesus' Wife fragment, is clearly a forgery and, moreover, written in the same hand and with the same instrument as those used for the Gospel of Jesus' Wife.[14][15]

Links to modern theories

The modern idea that Jesus was married is largely attributable to Holy Blood, Holy Grail. Its thesis was that Jesus had been married to Mary Magdalene, and that the legends of the Holy Grail were symbolic accounts of his bloodline in Europe. This thesis became much more widely circulated after it was made the center of the plot of The Da Vinci Code, a best-selling 2003 novel by author Dan Brown.[5][6][28] However, King rejected the link to The Da Vinci Code, telling the New York Times that she "wants nothing to do with the code or its author: 'At least, don’t say this proves Dan Brown was right.'" [5] The name of Jesus' wife is not given in the papyrus fragment.

Other text

The fragment also includes the line, "she will be able to be my disciple". The New York Times article notes that scholars date debates over "whether Jesus was married, whether Mary Magdalene was his wife and whether he had a female disciple to the early centuries of Christianity."[5] King asserts that it is clear from the first century canonical gospels that Jesus had female disciples, and it is her contention that, prior to the recently published papyrus fragment, no texts exist which claim that Jesus was married.[5]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Asked her handling of the public disclosure of the fragment, King admitted that she had, "...misjudged just how inflammatory that title would turn out to be". According to the interviewer, "she's been asking around for ideas on a new, less exciting name".

- ↑ Law No. 117, enacted on 6 August 1983

- ↑ One of the organisers of the Congress at which Professor King delivered her paper

References

- ↑ The Lessons of Jesus' Wife by Tom Bartlett (The Chronicle of Higher Education, 1 October 2012)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "The Gospel of Jesus's Wife: A New Coptic Gospel Papyrus". Harvard Divinity School. Retrieved 2012-09-19.

- ↑ Joel Baden and Candida Moss (December 2014). "The Curious Case of Jesus’s Wife". The Atlantic.

- ↑ "Harvard scholar's discovery suggests Jesus had a wife". Fox News (via Associated Press). 18 September 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-19.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 A Faded Piece of Papyrus Refers to Jesus' Wife by Laurie Goodstein (New York Times, 18 September 2012)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 O'Leary, Naomi (28 September 2012). ""Gospel of Jesus' wife" fragment is a fake, Vatican says". Reuters. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ↑ Brown, Andrew (16 October 2012). "The gospel of Jesus's wife: a very modern fake". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ "Q&A The Gospel of Jesus's Wife". Harvard University.

- ↑ "Scroll that mentions Jesus's wife is ancient, scientists confirm". Phys.org. 10 April 2014.

- ↑ "'Gospel of Jesus' Wife' Papyrus Is Ancient, Not Fake, Scientists And Scholars Say". The Huffington Post. 10 April 2014.

- ↑ "Testing Indicates "Gospel of Jesus's Wife" Papyrus Fragment to be Ancient". Harvard.edu. 10 April 2014.

- ↑ "Papyrus referring to Jesus' wife not a forgery, tests indicate". Thestar.com. 11 April 2014.

- ↑ "Is the fragment a forgery (a modern fabrication)?". The Gospel of Jesus's Wife. Harvard Divinity School. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Pattengale, Jerry (1 May 2014). "How the 'Jesus' Wife' Hoax Fell Apart". Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Goodstein, Laurie (4 May 2014). "Fresh Doubts Raised About Papyrus Scrap Known as ‘Gospel of Jesus’ Wife’". The New York Times.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Authenticity Of The 'Gospel Of Jesus's Wife' Called Into Question". The Huffington Post. 25 April 2014.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Baden, Joel S.; Moss, Candida R. (29 April 2014). "New clues cast doubt on 'Gospel of Jesus' Wife'". CNN.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "The Gospel Of Jesus' Wife," New Early Christian Text, Indicates Jesus May Have Been Married by Jaweed Kaleem (Huffington Post, 18 September 2012)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Sabar, Ariel (September 18, 2012). "The Inside Story of the Controversial New Text About Jesus". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ "Gospel of Jesus's Wife" revealed in Rome by Harvard scholar by David Trifunov (Global Post, 18 September 2012)

- ↑ Was Jesus married? New papyrus fragment fuels debate (Sydney Morning Herald, 19 September 2012)

- ↑ Marrapodi, Eric (January 3, 2013). "'Jesus Wife' fragment gets more testing, delays article". CNN Belief Blog. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ Karen L. King (April 2014). ""Jesus said to them, ‘My wife…’": A New Coptic Gospel Papyrus" (PDF). Harvard Theological Review 107 (2).

- ↑ Harvard professor identifies scrap of papyrus suggesting some early Christians believed Jesus was married by Lisa Wangsness (Boston Globe, 18 September 2012)

- ↑ Ancient text has Jesus referring to "my wife" (CBC News, 18 September 2012)

- ↑ HDS scholar announces existence of new early Christian gospel from Egypt (Harvard Divinity School, 18 September 2012)

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 The Gospel of Jesus's Wife, directed by Andy Webb (Blink Films for Smithsonian Channel, September 2012)

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Reality check on Jesus and his "wife" by Alan Boyle (NBCNews.com, 18 September 2012)

- ↑ Reality Check: The "Jesus’ Wife" Coptic Fragment by Daniel B. Wallace (danielbwallace.com, 21 September 2012)

- ↑ "Jesus Wife" Research Leads To Suspicions That Artifact Is A Fake by Jaweed Kaleem (Huffington Post, 26 September 2012)

- ↑ Gospel of Jesus's Wife is fake, claims expert by Andrew Brown (The Guardian, 21 September 2012)

- ↑ How The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife Might Have Been Forged, by Andrew Bernhard (October 11, 2012)

- ↑ A papyrus adrift by Alberto Camplani (L'Osservatore Romano, 28 September 2012)

- ↑ King, Karen L. (2014). "Jesus said to them, 'My wife...': A New Coptic Papyrus Fragment". Harvard Theological Review 107 (2): 131–159. doi:10.1017/S0017816014000133. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- ↑ Goodstein, Laurie (April 10, 2014). "Papyrus Referring to Jesus' Wife Is More Likely Ancient Than Fake, Scientists Say". New York Times. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

External links

- Beasley, Jonathan (September 18, 2012). "HDS Scholar Announces Existence of a New Early Christian Gospel from Egypt". Harvard Divinity School. Retrieved 2 July 2014. - official announcement

- The Gospel of Jesus's Wife at Harvard Divinity School website

- The Curious Case of Jesus’s Wife in The Atlantic