Golden Age of Comic Books

| Golden Age of Comic Books | |

|---|---|

|

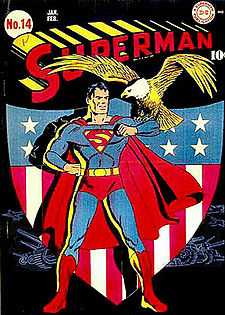

Superman, catalyst of the Golden Age: Superman #14 (Feb. 1942). Cover art by Fred Ray. | |

| Time span | c.1938 – c.1950 |

| Related periods | |

| Followed by | Silver Age of Comic Books (1956 – c. 1970) |

The Golden Age of Comic Books describes an era of American comic books, from the late 1930s to the early 1950s. During this time, modern comic books were first published and rapidly increased in popularity. The superhero archetype was created, and many famous characters debuted, including Superman, Batman, Captain America, Wonder Woman, and Captain Marvel.

Origin of the term

The first recorded use of the term "Golden Age" was by Richard A. Lupoff in an article called "Re-Birth" in issue 1 of Fanzine's Comic Art in April 1960.

History

The major event many cite as marking the beginning of the Golden Age was the 1938 debut of Superman in Action Comics #1,[1] published by Detective Comics, Inc.,[2] a corporate predecessor of modern-day DC Comics. The ensuing popularity of Superman helped make comic books a major form of publishing.[3] Companies such as Timely Comics, Quality Comics, Harvey Comics and MLJ, among others, created superheroes of their own in an effort to emulate the success of Superman.

Between 1939 and 1941, Detective Comics, Inc and its sister company All-American Publications introduced such popular superheroes as Batman and Robin, Wonder Woman, the Flash, Green Lantern, the Atom, Hawkman, and Aquaman. Timely, the 1940s predecessor of Marvel Comics, had million-selling titles that featured the Human Torch, the Sub-Mariner, and Captain America.

While DC and Timely characters are widely known today, circulation figures suggest that the best-selling superhero title of the era was Fawcett Comics' Captain Marvel, whose approximately 1.4 million copies per issue made it "the most widely circulated comic book in America". The comic was issued biweekly at one point to capitalize upon that popular interest.[4]

Other popular and long-running characters included Quality Comics' Plastic Man and cartoonist Will Eisner's non-superpowered masked detective the Spirit, originally published as a syndicated Sunday-newspaper insert in a quasi-comic book format.

Comic books, particularly superhero titles, gained immense popularity during World War II as cheap, portable, and easily read tales of good triumphing over evil. Heroes battles the Axis Powers: covers such as that of Captain America Comics #1 (cover-dated March 1941), published before the US entered the War, showed superheroes punching Nazi leader Adolf Hitler.

Many genres appeared on the newsstands, including humor, Western, romance, and jungle stories. The Steranko History of Comics 2 notes that it was the non-superhero characters of Dell Comics — most notably the licensed Walt Disney animated character comics — that outsold all the supermen of the day. Dell Comics, featuring such licensed movie and literary properties as Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Roy Rogers, and Tarzan, boasted circulations of over two million copies a month, and Donald Duck writer-artist Carl Barks is considered one of the era's major talents.[5]

Post-war

Nuclear topics began to appear in comics following the end of World War II. In the movie serial Atom Man vs. Superman, the titular hero fought a villain named Atom Man. The educational comic book Dagwood Splits the Atom used characters from the comic strip Blondie.[6] Superheroes with nuclear-derived powers began to emerge, such as the Atomic Thunderbolt and Atoman. Contrasting these serious characters were atomic funny animal characters such as Atomic Mouse and Atomic Rabbit. One historian argues that these cute creations helped ease young readers' fears over the prospect of nuclear war and neutralize anxieties over the questions posed by atomic power.[7]

A few long-running humor comics debuted during this period, such as EC's Mad and Carl Barks' Uncle Scrooge in Dell's Four Color Comics both in 1952. United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency was created in 1953, and after the publication of Fredric Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent in 1954, comics publishers such as EC's William Gaines were called to testify. The Comics Code Authority was created by the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers, leading EC to cancel all of its crime and horror comics, and focus mainly on Mad.

Shift from superheroes

In the late 1940s, the popularity of superhero comics waned, and in an effort to retain readers, comic publishers diversified into other genres such as war, Western, science fiction, romance, crime and horror comics.[8] Many superhero titles were cancelled or converted to other genres.

- DC Comics - In 1946, Superboy, Aquaman and Green Arrow were moved out of More Fun Comics into Adventure Comics, so that More Fun could focus on humor. In 1948, All American Comics featuring Green Lantern, Johnny Thunder and Dr. Midnite was replaced with All-American Western. In 1949, Flash Comics and Green Lantern were cancelled. In 1951, All Star Comics featuring the Justice Society of America became All-Star Western. In 1952, Star-Spangled Comics featuring Robin was retitled Star Spangled War Stories. Sensation Comics featuring Wonder Woman was cancelled in 1953. The only DC superhero comics to continue publication throughout the 1950s were Action Comics, Adventure Comics, Batman, Superboy, Superman, Wonder Woman and World's Finest Comics.

- Plastic Man appeared in Quality Comics' Police Comics until 1950 when its focus switched to regular detective stories.

- Timely Comics' The Human Torch was canceled with #35 (March 1949),[9] and Marvel Mystery Comics, starring the Human Torch, with #92 (June 1949), when it became the horror comic Marvel Tales.[10] Sub-Mariner Comics was cancelled with #32 (June 1949), and Captain America Comics (by then Captain America's Weird Tales) with #75 (Feb. 1950). The three heroes experienced a brief, unsuccessful revival in 1954.

- Harvey Comics' Black Cat was cancelled in 1951.

- Lev Gleason Publications' Daredevil was edged out of his own title by the Little Wise Guys in 1950.

- Fawcett Comics' Whiz Comics, Master Comics and Captain Marvel Adventures were cancelled in 1953, and The Marvel Family was cancelled in 1954.

The subsequent Silver Age of Comic Books is generally recognized as beginning with the debut of the first successful new superhero since the Golden Age, DC Comics' new Flash, in Showcase #4 (Oct. 1956).

See also

- List of Golden Age of Comics publishers

- Silver Age of Comic Books

- Bronze Age of Comic Books

- Modern Age of Comic Books

- List of Marvel Comics Golden Age characters

References

- ↑ "The Golden Age of Comics". History Detectives: Special Investigations. PBS. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

The precise era of the Golden Age is disputed, though most agree that it was born with the launch of Superman in 1938.

- ↑ "Action Comics #1". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved 2015-02-16.

- ↑ Goulart, Ron (2000). Comic book Culture: An Illustrated History (1st American ed.). Portland, Oregon: Collectors Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-888054-38-5.

- ↑ Morse, Ben (July 2006). "Thunderstruck". Wizard (179).

- ↑ Wivel, Matthias (January 24, 2012). "Reviews: Donald Duck Lost in the Andes". The Comics Journal.

[H]is [Barks'] work of c. 1948–54 ranks amongst the most consistently inspired, inventive, touching, and plain fun in the history of comics.

- ↑ "Dagwood splits the atom | The Ephemerist". Sparehed.com. 2007-05-14. Retrieved 2015-02-02.

- ↑ Zeman, Scott C.; Amundson, Michael A. (2004). Atomic Culture: How We Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb ([Nachdr.] ed.). Boulder, Colo.: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 9780870817632.

- ↑ Kovacs, George; Marshall, C. W. (2011). Classics and Comics. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0199734191.

- ↑ "The Human Torch". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved 2015-02-03.

- ↑ "Marvel Mystery Comics". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved 2015-02-03.

External links

- Don Markstein's Toonopedia

- Digital Comic Museum (scans of presumed public domain Golden Age comics)

- Jess Nevins' Encyclopedia of Golden Age Superheroes

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||