Gofraid mac Amlaíb meic Ragnaill

| Gofraid mac Amlaíb meic Ragnaill | |

|---|---|

| King of Dublin | |

The remains of Skuldelev 2 may be evidence that Gofraid aided the Danes against the Norman King of England. | |

| Reign | 1072–1075 |

| Predecessor | Diarmait mac Máel na mBó |

| Successor | Muirchertach Ua Briain |

| Dynasty | possibly Uí Ímair |

| Died | 1075 |

Gofraid mac Amlaíb meic Ragnaill[note 1] (d. 1075) was a late 11th-century King of Dublin. Although the identities of his father (Amlaíb) and grandfather (Ragnall) are uncertain, Gofraid was probably one of the Uí Ímair. He may have been a nephew of Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, King of Dublin, who was driven from Dublin in 1052 by the Uí Ceinnselaig King of Leinster. When this Leinster king died in 1072, Dublin was seized by the Uí Briain King of Munster, who appears to have handed the Dublin kingship over to Gofraid.

Gofraid's reign only lasted a few years, and he may not have had much independence from his Uí Briain overlord. In 1075, Irish records state that Gofraid was banished from Ireland, and that he died the same year whilst assembling a large fleet. The remains of an 11th-century Danish longship may be evidence that Gofraid lent military assistance to the King of Denmark, who participated in military operations against the Norman King of England in the years following the Norman Conquest.

Background

Domination of Norse-Gaelic Dublin was much sought over by leading Irish kings in the 11th century.[6] By the middle of the century, the town's defended area spanned about 12 hectares (30 acres), and its population may have been about 4,500.[7] The Kings of Dublin also ruled Fine Gall (roughly corresponding to modern Fingal), a northern agricultural hinterland of Dublin.[8]

In 1046, the Kingship of Dublin was seized by Echmarcach mac Ragnaill (d. 1065).[9] The parentage of this Norse-Gaelic king is uncertain. While it is just possible that his father was Ragnall (d. 980), son of Amlaíb Cuarán,[10] a more likely possibility may be that his father was either Ragnall (d. 1015 or 1018), son of Ímar of Waterford, or else this Ragnall's son of the same name who died in 1035. Another alternative, which may be the most likely, is that Echmarcach's father was Ragnall mac Gofraid, King of the Isles (d. 1004 or 1005), son of Gofraid mac Arailt, King of the Isles (d. 989).[11] Echmarcach's father (whoever he may have been) may have been Gofraid's paternal-grandfather.[12][note 2] Gofraid's patronym, Gofraid mac Amlaíb meic Ragnaill, literally means "Gofraid, son of Amlaíb, son of Ragnall".

In 1052, Echmarcach was driven from Ireland by Diarmait mac Máel na mBó, King of Leinster (d. 1072).[17] For the next twenty years, Diarmait thus had control over the Dublin's highly rated army and prized fleet of warships,[18] and the town became the capital of Leinster.[19] On Diarmait's unexpected death in 1072, Toirdelbach Ua Briain, King of Munster (d. 1086) invaded Leinster, and followed up on this military success with the acquisition of Dublin.[20] The Annals of Innisfallen claim that the Dubliners offered the kingship to Toirdelbach.[21] Although this record may be mere Uí Briain propaganda, it is also possible that the Dubliners may have preferred a distant overlord from Munster rather than one from neighbouring Leinster.[14]

King of Dublin

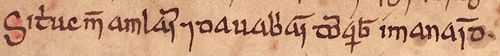

Following the Uí Briain takeover of Dublin, Toirdelbach appears to have handed the region over to Gofraid,[22] who is titled "king" by the Annals of Innisfallen in 1072.[21] The great distance between Munster (Toirdelbach's centre of power) and Dublin was probably a factor in this action.[23] Uí Briain involvement in the Isles soon followed their acquisition of Dublin. In 1073, the Annals of Ulster state that the Isle of Man was raided by a certain Sitric mac Amlaíb and two grandsons of Brian Bóruma, High King of Ireland.[24] The precise identity of the slain raiders is unknown, as are the circumstances of the expedition. However, it is very likely that this event was closely connected to the recent Uí Briain takeover of Dublin.[22] Considering Gofraid's position, and the possibility that he was related to Echmaracach[25] (who appears to have had familial connections to the Uí Briain),[26][note 3] the Sitric who led the attack may well have been Gofraid's brother.[29]

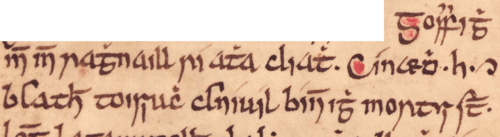

When Dúnán, Bishop of Dublin died in 1074, Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury (d. 1089) was petitioned by Gofraid, on behalf of the clergy and people of Dublin, to consecrate Gilla Pátraic (d. 1084) as Dúnán's successor.[30] When Lanfranc sent Gilla Pátraic to Ireland, he dispatched a letter to Gofraid which urged the king to correct moral laxities among his people (practices such as divorce, remarriage, and concubinage). The archbishop also sent a similar letter to Toirdelbach.[31] These Latin letters call Gofraid gloriosius Hiberniae rex ("the glorious King of Ireland")[32] and Toirdelbach magnificus Hiberniae rex,[33] and appear to indicate that Lanfranc was aware Gofraid had little independence during his kingship, and that he was closely bound to the authority of his Uí Briain overlord.[34]

Unfortunately for Gofraid, his rule over Dublin did not last long. The Annals of Innisfallen state that he was banished "over sea" by Toirdelbach, and that Gofraid died "beyond sea", having assembled a "great fleet" to come to Ireland.[35] Gofraid may thus have fled to the Kingdom of the Isles, and died whilst gathering a fleet to invade Dublin.[36] With Gofraid thus removed, the Uí Ceinnselaig took control of Dublin in form of Diarmait's grandson, Domnall mac Murchaid (d. 1075). Domnall may well have ruled on Toirdelbach's behalf, although unfortunately for him and the Uí Ceinnselaig, Domnall soon died of illness in 1075.[37] Toirdelbach then appointed his eldest son, Muirchertach (d. 1119), as King of Dublin.[38]

Possible Anglo-Danish involvement

It is uncertain why Gofraid was ejected from Dublin.[39] Domnall's brief rise to power immediately after Gofraid's fall could suggest that the latter was involved in an Uí Ceinnselaig takeover of Dublin.[40] Another possibility is that Gofraid may have been actively engaged in the ongoing opposition to the Norman regime, which ruled the recently conquered Kingdom of England.[41] Diarmait, Gofraid's predecessor in Dublin, was a close ally of Harold Godwinsson, before Harold became King of England in 1066. After Harold's fall, Diarmait supported the efforts of the disaffected English opponents of William I, King of England. For example, according to William of Malmesbury, the defeated English aristocracy fled to Ireland and Denmark following the Norman Conquest. Diarmait sheltered two of Harold's sons in the years immediately following the conquest. From Ireland, the sons launched two sea-borne attacks on England's south-western coast—one in 1068 and one 1069. The attack of 1069 may have been intended to coincide with the northern English revolt and Danish invasion of the same year.[42] According to English chronicler Orderic Vitalis, Diarmait lent sixty ships to the expedition of 1069.[43]

In 1075, an English revolt against the Norman regime was led by Roger, Earl of Hereford, Ralph, Earl of East Anglia, and Waltheof, Earl of Northumbria. The uprising was timed to take place when William was away on the continent. The revolt was also strengthened by Danish support, in the form of a fleet of two hundred ships, led by Knútr Sveinnsson (d. 1086),[40] brother of Haraldr Sveinnsson, King of Denmark.[44][note 4] Unfortunately for the rebels, the uprising was quelled largely due to the actions of Wulfstan, Bishop of Worcester, and by the time Knútr's fleet reached the English coast, the revolt was utterly crushed.[40]

Considering the Irish dimension in previous actions against the Norman regime, Gofraid may have been involved in the actions of 1075. A 12th-century eulogy composed for Knútr states that Knútr's fame was known as far as Ireland, and could be evidence of relations between Ireland and Denmark during Toirdelbach's overlordship.[41] Furthermore, a longship, determined to have been built in Dublin in about 1042, was recovered from Roskilde Fjord[43] in the mid 20th century.[45] The longship itself (called Skuldelev 2) appears to have been repaired in about 1075, and may be evidence that Gofraid was supplying the Danes with warships.[43]

However, just as Diarmait supported William's English opponents, Toirdelbach appears to have ushered in an era of co-operation with the Norman King of England.[46] If Dubliners were indeed involved in the English revolt of 1075, this may well have led to Gofraid's expulsion by his pro-Norman Uí Briain overlord.[47] It is also possible that the record of Gofraid's "great fleet" in 1075 may actually refer to Knútr's fleet of the same year—a fleet which may have been regarded by the annalist to have been affiliated with the exiled Gofraid.[48]

Family connections

The chart below illustrates possible immediate relations of Gofraid. Gofraid and his certain relations are coloured green; his possible relations are coloured red; women are italicised.

Gofraid's father, Amlaíb, may have been the father of Sitric mac Amlaíb (d. 1073). Gofraid's grandfather, Ragnall, may have been the father of the Echmarcach mac Ragnaill (d. 1065). Echmarcach appears to have the brother of Cacht ingen Ragnaill, who married Donnchad mac Briain, King of Munster. The "grandsons of Ragnall", who attacked Mann in 1087 may have been brothers of Gofraid, or possibly sons of Echmarcach.

Gofraid may have been the uncle of Toirdelbach's daughter-in-law, Mór.[49]

| Ragnall | Brian Bóruma (d. 1014) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amlaíb | Echmarcach (d. 1065) | Cacht (d. 1054) | Donnchad (d. 1065) | Tadc (d. 1023) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gofraid (d. 1075) | Sitric (d. 1073) | "Ragnall's grandsons" (d. 1087) | Toirdelbach (d. 1086) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ Scholars have rendered Gofraid's name variously in recent secondary sources: Godfrey,[1] Godred,[2] Gofraid,[3] Guthric,[4] and Guðrøðr.[5]

- ↑ According to scholars Seán Duffy and Richard Oram, Echmarcach's father was either the son of Ímar, or else the son of this son of Ímar.[13] Duffy has regarded it possible that Gofraid was Echmarcach's nephew. Duffy termed the descendants of Ragnall as the Uí Ragnaill,[14] while Oram termed them the meic Ragnaill.[15] On the other hand, according to scholars Cólman Etchingham, Benjamin Hudson, and Alex Woolf, Echmarcach's father was probably the son of Gofraid mac Arailt.[11] Hudson has regarded Gofraid mac Amlaíb meic Ragnaill to be Echmarcach's nephew.[16]

- ↑ According to the Banshenchas, a daughter of Echmarcach was married to Tadc, son of Toirdelbach Ua Briain (grandson of Brian Bóruma). The Banshenchas states that the couple had three sons and a daughter: Donnchad, Domnall, Amlaíb, and Bé Binn.[27] Echmarcach may have been the brother of Cacht ingen Ragnaill, wife of Donnchad mac Briain.[28]

- ↑ Godwine's paternal-grandmother, Gytha, was Sveinn's paternal-aunt.[43]

Citations

- ↑ Hudson 2005b.

- ↑ Hudson 2005a.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005. See also: Ó Corráin 2001. See also: Duffy 1992.

- ↑ Flanagan 2004.

- ↑ Downham 2004. See also: Hudson 1994.

- ↑ Ó Corráin 2001: p. 26.

- ↑ Clarke 2005: p. 135.

- ↑ Downham 2005: pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Hudson 2005b: p. 137.

- ↑ Hudson 2005b: p. 129.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Woolf 2007: p. 246. See also: Hudson 2005b: pp. 129, 130 fig 4. See also: Etchingham 2001.

- ↑ Hudson 2005b: p. 130 fig 4. See also: Duffy 1992: p. 102.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: pp. 227–228. See also: Duffy 1992: p. 102.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Duffy 1992: p. 102.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Hudson 2005b: pp. 130 fig 4.

- ↑ Duffy 1992: p. 94.

- ↑ Duffy 1993: p. 13.

- ↑ Duffy 2009: p. 291.

- ↑ Bracken 2004. See also: Duffy 1992: p. 101.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Duffy 1992: p. 102. See also: Mac Airt; Färber 2008: 1072.4.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: p. 232. See also: Duffy 1992: p. 102.

- ↑ Duffy 1993: pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: p. 232. See also: Bambury; Beechinor 2000: 1073.5.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: p. 232.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: p. 232. See also: Duffy 1992: p. 105.

- ↑ Duffy 1992: p. 105, 105 fn 59.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: p. 232. See also: Hudson 2005b: p. 134.

- ↑ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: p. 232. See also: Hudson 2005a: p. 463.

- ↑ Cowdrey 2004. See also: Flanagan 2004. See also: Hudson 1994: pp. 149–150. See also: Duffy 1992: p. 102 fn 45. See also: Erlington; Todd 1847: pp. 488–489.

- ↑ Flanagan 2004. See also: Duffy 1992: p. 102 fn 45.

- ↑ Flanagan 2008: pp. 904–905. See also: Hudson 1994: pp. 149–150. See also: Duffy 1992: p. 102 fn 45. See also: Munch; Goss 1874: pp. 266–268. See also: Erlington; Todd 1847: pp. 490–491.

- ↑ Flanagan 2008: pp. 904–905. See also: Hudson 1994: pp. 149–150. See also: Duffy 1992: p. 102 fn 45. See also: Erlington; Todd 1847: pp. 492–493.

- ↑ Flanagan 2008: pp. 904–905. See also: Duffy 1992: p. 102 fn 45. See also: Hudson 1994: pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Hudson 2005b: p. 167. See also: Duffy 1992: p. 102. See also: Mac Airt; Färber 2008: 1075.2.

- ↑ Hudson 2005b: p. 167.

- ↑ Duffy 1992: pp. 102–103. See also: Mac Airt; Färber 2008: 1075.3. See also: Priour; Beechinor 2008: 1075.6. See also: Bambury; Beechinor 2000: 1075.4.

- ↑ Hudson 2005b: p. 167. See also: Bracken 2004. See also: Duffy 1993: p. 15. See also: Duffy 1992: pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Hudson 2005a: p. 463. See also: Hudson 2005b: p. 167. See also: Hudson 1994: p. 152.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Hudson 1994: p. 152.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Hudson 2005b: p. 167. See also: Hudson 1994: p. 152.

- ↑ Hudson 1994: pp. 146–148.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Downham 2004: pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Hudson 1994: p. 152 fn 39.

- ↑ Viking dig reports, BBC Online, retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ↑ Hudson 1994: pp. 155–158.

- ↑ Hudson 1994: pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Duffy 2009: pp. 295–296.

- ↑ Hudson 2005a: p. 463.

References

- Primary sources

- Bambury, Pádraig; Beechinor, Stephen, eds. (2000), The Annals of Ulster (16 December 2009 ed.), CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, retrieved 22 June 2012.

- Beechinor, Stephen; Priour, Myriam, eds. (2008), Annals of the Four Masters (11 September 2011 ed.), CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, retrieved 9 July 2012.

- Elrington, Charles Richard; Todd, James Henthorn, eds. (1847), The whole works of the Most Rev. James Ussher 4, Hodges and Smith.

- Mac Airt, Seán; Färber, Beatrix, eds. (2008), Annals of Inisfallen (16 February 2010 ed.), CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, retrieved 22 June 2012.

- Munch, Peter Andreas; Goss, Alexander, eds. (1874), Chronica regvm Manniæ et Insvlarvm: the chronicle of Man and the Sudreys; from the manuscript codex in the British Museum; with historical notes 2, printed for the Manx Society.

- Secondary sources

- Bracken, Damian (2004), "Ua Briain, Muirchertach [Murtagh O'Brien] (c.1050–1119)", Oxford dictionary of national biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20464, retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Bracken, Damian (2004), "Ua Briain, Toirdelbach [Turlough O'Brien] (1009–1086)", Oxford dictionary of national biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20468, retrieved 5 July 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Clarke, H. B. (2005), "Dublin", in Duffy, Seán; MacShamhráin, Ailbhe; Moynes, James, Medieval Ireland: an encyclopedia, Routledge, pp. 135–137, ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Cowdrey, H. E. J. (2004), "Lanfranc (c.1010–1089)", Oxford dictionary of national biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16004, retrieved 22 June 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Downham, Clare (2004), "England and the Irish-sea zone in the eleventh century", in Gillingham, John, Anglo-Norman studies XXVI: proceedings of the battle conference 2003, The Boydell Press, pp. 55–73, ISBN 9781843830726, ISSN 0954-9927.

- Downham, Clare (2005), "Fine Gall", in Duffy, Seán; MacShamhráin, Ailbhe; Moynes, James, Medieval Ireland: an encyclopedia, Routledge, pp. 170–171, ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Duffy, Seán (1992), "Irishmen and Islesmen in the kingdoms of Dublin and Man, 1052–1171", Ériu (Royal Irish Academy) 43: 93–133, JSTOR 30007421.

- Duffy, Seán (1993), "Pre-Norman Dublin: Capital of Ireland?", History Ireland (Wordwell) 1 (4): 13–18, JSTOR 27724114.

- Duffy, Seán (2009), "Ireland, c.1000–c.1100", in Stafford, Pauline, A companion to the early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500–c.1100, Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 285–302, ISBN 978-1-4051-0628-3.

- Etchingham, Cólman (2001), "North Wales, Ireland and the Isles: the insular viking zone", Peritia 15: 145–187, ISBN 250351152X.

- Flanagan, Marie Therese (2004), "Patrick (d. 1084)", Oxford dictionary of national biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21563, retrieved 22 June 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Flanagan, Marie Therese (2008), "High-kings with opposition, 1072–1166", in Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí; MacShamhráin, Ailbhe; Moynes, James, A new history of Ireland, Oxford University Press, pp. 899–933, ISBN 978-0-19-821737-4.

- Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard D.; Pedersen, Frederik (2005), Viking empires, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Hudson, Benjamin T. (1994), "William the Conqueror and Ireland", Irish Historical Studies (Irish Historical Studies Publications) 29 (114): 145–158, JSTOR 30006739.

- Hudson, Benjamin T. (2004), "Dúnán [Donatus] (d. 1074)", Oxford dictionary of national biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8199, retrieved 22 June 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Hudson, Benjamin T. (2005a), "Ua Briain, Tairrdelbach, (c. 1009–14 July 1086 at Kincora)", in Duffy, Seán; MacShamhráin, Ailbhe; Moynes, James, Medieval Ireland: an encyclopedia, Routledge, pp. 462–463, ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Hudson, Benjamin T. (2005b), Viking pirates and Christian princes: dynasty, religion, and empire in the north Atlantic, Oxford University Press.

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh (2001), "The Vikings in Ireland", in Larsen, Anne-Christine, The Vikings in Ireland, The Viking Ship Museum, pp. 17–27, ISBN 87 85180 42 4.

- Woolf, Alex (2007), From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070, The new Edinburgh history of Scotland, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-1233-8.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||