Glutamine

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Glutamine | |

| Other names

L-Glutamine (levo)glutamide 2-Amino-4-carbamoylbutanoic acid | |

| Identifiers | |

| Abbreviations | Gln, Q |

| ATC code | A16 |

| 56-85-9 | |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:28300 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL930 |

| ChemSpider | 718 |

| EC-number | 200-292-1 |

| |

| IUPHAR ligand | 723 |

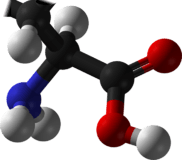

| Jmol-3D images | Image |

| KEGG | C00303 |

| PubChem | 738 |

| |

| UNII | 0RH81L854J |

| Properties[1] | |

| Molecular formula |

C5H10N2O3 |

| Molar mass | 146.14 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | decomposes around 185°C |

| soluble | |

| Chiral rotation ([α]D) |

+6.5º (H2O, c = 2) |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |

| Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |

| Except where noted otherwise, data is given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Glutamine (abbreviated as Gln or Q, and often called L-glutamine) is one of the 20 amino acids encoded by the standard genetic code. It is considered a conditionally essential amino acid.[2] Its side-chain is an amide formed by replacing the side-chain hydroxyl of glutamic acid with an amine functional group, making it the amide of glutamic acid. Its codons are CAA and CAG. In human blood, glutamine is the most abundant free amino acid, with a concentration of about 500–900 µmol/l.[3]

Functions

Glutamine plays a role in a variety of biochemical functions:

- Protein synthesis, as any other of the 20 proteinogenic amino acids

- Regulation of acid-base balance in the kidney by producing ammonium[4]

- Cellular energy, as a source, next to glucose[5]

- Nitrogen donation for many anabolic processes, including the synthesis of purines[3]

- Carbon donation, as a source, refilling the citric acid cycle[6]

- Nontoxic transporter of ammonia in the blood circulation

Producing and consuming organs

Producers

Glutamine is synthesized by the enzyme glutamine synthetase from glutamate and ammonia. The most relevant glutamine-producing tissue is the muscle mass, accounting for about 90% of all glutamine synthesized. Glutamine is also released, in small amounts, by the lung and the brain.[7] Although the liver is capable of relevant glutamine synthesis, its role in glutamine metabolism is more regulatory than producing, since the liver takes up large amounts of glutamine derived from the gut.[3]

Consumers

The most eager consumers of glutamine are the cells of intestines,[3] the kidney cells for the acid-base balance, activated immune cells,[8] and many cancer cells.[6] In respect to the last point mentioned, different glutamine analogues, such as DON, Azaserine or Acivicin, are tested as anticancer drugs.

Medical uses

In catabolic states of injury and illness, glutamine becomes conditionally essential requiring intake from food or supplements.[9]

Supplementation does not appear to have an effect in infants with significant problems of the stomach or intestines.[10]

Glutamine has been used as a component of oral supplementation to reverse cachexia (muscle wasting) in patients with advanced cancer[11] or HIV/AIDS.[12]

Glutamine oral supplementation significantly reduces the risk of systemic infections originating from the gut such as in critically ill individuals and in individuals who have had abdominal surgery. The reduction in rates of infections in these groups of people are due to glutamine improving intestinal barrier function including reducing increased intestinal permeability. Intravenous administration does not appear to produce these benefits, however.[13]

Research

In biological research, L-glutamine is commonly added to the media in cell culture.[14][15] However, the high level of glutamine in the culture media may inhibit other amino acid transport activities.[16]

Structure

Nutrition

Occurrences in nature

Glutamine is the most abundant naturally occurring, nonessential amino acid in the human body, and one of the few amino acids that can directly cross the blood–brain barrier.[17] In the body, it is found circulating in the blood, as well as stored in the skeletal muscles. It becomes conditionally essential (requiring intake from food or supplements) in states of illness or injury.[9]

Dietary sources

Dietary sources of L-glutamine include beef, chicken, fish, eggs, milk, dairy products, wheat, cabbage, beets, beans, spinach, and parsley. Small amounts of free L-glutamine are also found in vegetable juices.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Weast, Robert C., ed. (1981). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (62nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. C-311. ISBN 0-8493-0462-8..

- ↑ Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements, published by the Institute of Medicine's Food and Nutrition Board, currently available online at http://fnic.nal.usda.gov/dietary-guidance/dietary-reference-intakes/dri-reports

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Brosnan, John T. (June 2003). "Interorgan amino acid transport and its regulation". J. Nutr. 133 (6 Suppl 1): 2068S–2072S. PMID 12771367.

- ↑ Hall, John E.; Guyton, Arthur C. (2006). Textbook of medical physiology (11th ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. p. 393. ISBN 0-7216-0240-1.

- ↑ Aledo, J. C. (2004). "Glutamine breakdown in rapidly dividing cells: Waste or investment?". BioEssays 26 (7): 778–785. doi:10.1002/bies.20063. PMID 15221859.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Yuneva, M.; Zamboni, N.; Oefner, P.; Sachidanandam, R.; Lazebnik, Y. (2007). "Deficiency in glutamine but not glucose induces MYC-dependent apoptosis in human cells". The Journal of Cell Biology 178 (1): 93–105. doi:10.1083/jcb.200703099. PMC 2064426. PMID 17606868.

- ↑ Newsholme, P.; Lima, M. M. R.; Procopio, J.; Pithon-Curi, T. C.; Doi, S. Q.; Bazotte, R. B.; Curi, R. (2003). "Glutamine and glutamate as vital metabolites". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 36 (2): 153–163. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2003000200002. PMID 12563517.

- ↑ Newsholme, P. (2001). "Why is L-glutamine metabolism important to cells of the immune system in health, postinjury, surgery or infection?". The Journal of nutrition 131 (9 Suppl): 2515S–2522S; discussion 2522S–4S. PMID 11533304.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Glutamine". Medical Reference Guide. University of Maryland Medical Center. 2011-05-24. Archived from the original on 2009-12-09. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ↑ Brown, JV; Moe-Byrne, T; McGuire, W (15 December 2014). "Glutamine supplementation for young infants with severe gastrointestinal disease.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 12: CD005947. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005947.pub4. PMID 25504522.

- ↑ May, PE; Barber, A; D'Olimpio, JT; Hourihane, A; Abumrad, NN (April 2002). "Reversal of cancer-related wasting using oral supplementation with a combination of beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate, arginine, and glutamine.". American journal of surgery 183 (4): 471–9. PMID 11975938.

- ↑ "Glutamine". WebMD. WebMD, LLC. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- ↑ Rapin JR, Wiernsperger N (2010). "Possible links between intestinal permeability and food processing: A potential therapeutic niche for glutamine". Clinics (Sao Paulo) 65 (6): 635–43. doi:10.1590/S1807-59322010000600012. PMC 2898551. PMID 20613941.

- ↑ Thilly, William G. (1986). Mammalian cell technology. London: Butterworths. p. 110. ISBN 0-409-90029-X. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

13 amino acids in Eagle's popular culture medium...are arginine, cyst(e)ine, glutamine...

- ↑ Yang H, Roth CM, Ierapetritou MG. (2011) Analysis of amino acid supplementation effects on hepatocyte cultures using flux balance analysis, OMICS, A Journal of Integrative Biology, 15(7-8): 449–460.

- ↑ Yang H, Ierapetritou MG, Roth CM. (2010) Effects of amino acid transport limitations on cultured hepatocytes, Biophysical Chemistry, 152(1-3):89-98.

- ↑ Lee, W. J.; Hawkins, R. A.; Viña, J. R.; Peterson, D. R. (1998). "Glutamine transport by the blood-brain barrier: A possible mechanism for nitrogen removal". The American journal of physiology 274 (4 Pt 1): C1101–C1107. PMID 9580550.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||