Global Health Initiatives

Global Health Initiatives (GHIs) are humanitarian initiatives that raise and disburse additional funds for infectious diseases, such as AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; for immunization; and for strengthening health systems in developing countries.

Examples of GHIs are the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), and the World Bank’s Multi-country AIDS Programme (MAP), all of which focus on HIV/AIDS. The GAVI Alliance (formerly The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation) focuses on immunization, particularly with respect to child survival.

GHI Functions

In terms of their institutional structure, GHIs have little in common with each other. In terms of their function – specifically their ability to raise and disburse funds, provide resources and coordinate and/or implement disease control in multiple countries – GHIs share some common ground, even if the mechanisms through which each of these functions is performed are different.[1]

PEPFAR - an initiative established in 2003 by the Bush Administration - and PEPFAR II (PEPFAR’s successor in 2009 under the Obama Administration[2]) are bilateral agreements between the United States and a recipient of its development aid for HIV/AIDS – typically an international non-government organisation INGO or a recipient country’s government. The Global Fund, established in 2002, and the GAVI Alliance, launched in 2000, are public-private partnerships that raise and disburse funds to treat AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and for immunization and vaccines. The World Bank is an International financial institution. It is the largest funder of HIV/AIDS within the United Nations system and has a portfolio of HIV/AIDS programmes dating back to 1989.[3] In 1999, the Bank launched the first phase of its response to HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa – the MAP. This came to an end in 2006 when a second phase – Agenda for Action 2007-11 – came into effect.

GHI Funding

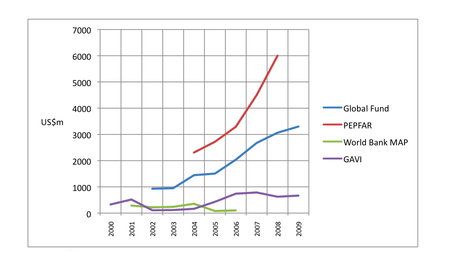

Tracking funding from GHIs is not easy.[5] However, it is possible to determine the amounts of funding GHIs commit and disburse from sources such as the OECD CRS online database, as well as data provided by individual GHIs (Figure 1).

Since 1989, the World Bank has committed approximately US$4.2bn in loans and credits for programs, and has disbursed US$3.1bn. Of this total, the Bank's MAP has committed US$1.9bn since 2000. Through bilateral contributions to HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis programmes and donations to the Global Fund, PEPFAR has donated approximately US$25.6bn since 2003. In July 2008, the U.S Senate re-authorised a further US$48 bn over five years for PEPFAR II, of which US$6.7bn has been requested for FY 2010. During the period 2001-2010, donors have pledged US$21.1bn to the Global Fund, of which US$15.8bn has been paid by donors to the Fund. Gavi has approved US$3.7bn for the period 2000-2015[6]

Impact of GHIs on Country Health Systems

There is much discussion about the extent to which the volume of these additional funds creates multiple effects that impact – positively and negatively – on health outcomes for specific diseases and also on health systems themselves. Assessing the impact of GHIs on specific diseases and health systems is also notoriously difficult, not least because of the problem of attributing particular effects to individual GHIs.[7] A common response in evaluations of GHIs, therefore, is to acknowledge the inherent limitations of establishing causal chains in what is a highly complex public health environment, and to base conclusions on adequacy statements resulting from trends that demonstrate substantial growth in process and impact indicators.[8]

However, it is with this very approach towards evaluating Global Health Initiatives that the social determinants of a disease are simply overlooked, as implementers and evaluators are not willing to tackle the complexity of a disease within the larger social, political, cultural, and environmental system. Even if an effective evaluation of the impacts of the GHI is carried out, perhaps showing a decrease in prevalence of the disease, we can not truly understand the long-term impacts of the GIH or expect the positive results to last if we have not addressed the root social, political, or environmental causes of the disease. In this respect, GHI should be less concerned about eradicating specific diseases, instead focusing first on basic living conditions, such as sanitation and access to nutritious food, that are essential in delivering a sustainable heath program [9]

Research on the effects of GHIs

A small number of institutions have shaped, and continue to shape, research on GHIs. In 2003, researchers at Abt Associates devised an influential framework for understanding the system-wide effects of the Global fund which has informed much subsequent research, including their own studies of system-wide effects of the Global Fund in Benin, Ethiopia, Georgia and Malawi - often referred to as the 'SWEF' studies.[10]

Abt continues to support ongoing research on the effects of GHIs in multiple countries. The Washington-based Center for Global Development has also been very active in its analysis of GHIs, particularly PEPFAR financing. The Center's HIV/AIDS Monitor is essential reading for researchers of GHIs. With hubs in London and Dublin, the Global Health Initiatives Network (GHIN) has been coordinating and supporting research in 22 countries on the effects of GHIs on existing health systems.

Knowledge of the effects of GHIs on specific diseases and on health systems comes from multiple sources.Longitudinal studies enable researchers to establish baseline data and then track and compare GHI effects on disease control or country health systems over time. In addition to Abt Associates' SWEF studies, additional early examples of this type of analysis were three-year, multi-country studies of the Global Fund in Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia.[11] In 2009, research findings were published from tracking studies in Kyrgyzstan, Peru and Ukraine that sought to identify the health effects of the Global Fund at national and sub-national levels.

In contrast to longitudinal studies, multi-country analyses of GHIs can provide a ‘snapshot’ of GHI effects but are often constrained by “aggressive timelines”.[12] The Maximising Positive Synergies Academic Consortium, for example, reported in 2009 on the effects of the Global Fund and PEPFAR on disease control and health systems, drawing on data from 20 countries.[13] Most GHI evaluations – both internally and externally commissioned – rely on this type of short-term analysis and, inevitably, there is often a trade-off between depth and breadth of reporting.

Synthesis of data from multiple sources is an invaluable resource for making sense of the effects of GHIs. Early synthesis studies include a 2004 synthesis of findings on the effects of the Global Fund in four countries[14] by researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), a 2005 study by McKinsey & Company[15] and an assessment of the comparative advantages of the Global Fund and World Bank AIDS programs.[16]

Two wide-ranging studies were published in 2009: a study of interactions between GHIs and country health systems commissioned by the World Health Organisation[17] and a study by researchers from LSHTM and the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. The latter study - The effects of global health initiatives on country health systems: a review of the evidence from HIV/AIDS control – reviewed the literature on the effects of the Global fund, the World Bank MAP and PEPFAR on country health systems with respect to: 1) national policy; 2) coordination and planning; 3) stakeholder involvement; 4) disbursement, absorptive capacity and management; 5) monitoring & evaluation; and 6) human resources (Table 2).

Evaluations of GHIs

Each of the four GHIs summarised has been evaluated at least once since 2005 and all four produce their own annual reports.

World Bank MAP

A comprehensive study of MAP programs published in 2007 reviewed whether MAP was implemented as designed, but did not evaluate MAP or assess its impact. In addition, there have been two evaluations that provide important additional insight into the effectiveness of the Bank's HIV/AIDS programmes (though not specifically MAP focused). In 2005, the Bank conducted an internal evaluation - Committing to Results: Improving the Effectiveness of HIV/AIDS Assistance - which found that National AIDS strategies were not always prioritised or costed.

Supervision, and monitoring and evaluation (M&E), were weak; civil society had not been engaged; political commitment and capacity had been overestimated, and mechanisms for political mobilisation were weak; and bank research and analysis, whilst perceived to be useful, was not reaching policy makers in Africa. In 2009, a hard-hitting evaluation of the Bank’s Health, Nutrition and Population support – Improving Effectiveness of Outcomes for the Poor in Health, Nutrition and Population – found that a third of the Bank’s HNP lending had not performed well, and that while the performance of the Bank’s International Finance Corporation investments had improved, accountability was weak.

Global Fund

A five-year, comprehensive evaluation of the Global Fund published a synthesis report in 2009 of findings from three Study areas. The Fund’s Technical Evaluation Research Group (TERG) Five Year Evaluation (5YE) of the Global Fund drew on data from 24 countries to evaluate the Fund’s organisational effectiveness and efficiency, partnership environment and impact on AIDS, TB and Malaria. The Evaluation highlighted the possible decline in HIV incidence rate in some countries, and rapid scale up of funding for HIV/AIDS, access and coverage, but also identified major gaps in support for national health information systems, and poor drug availability.

GAVI Alliance

In 2008, an evaluation of GAVI’s vaccine and immunization support - Evaluation of the GAVI Phase 1 performance - reported increased coverage of HepB3, Hib3 and DTP3 and increased coverage in rural areas but also a lack of cost data disaggregated by vaccine that prevented GAVI from accurately evaluating the cost effectiveness of its programs and vaccines, and an “unrealistic” reliance by GAVI on the market to reduce the cost of vaccines.[18] The same year, a study of the financial sustainability of GAVI vaccine support - Introducing New Vaccines in the Poorest Countries: What did we learn from the GAVI Experience with - found that although GAVI funding equated to $5 per infant in developing countries per year for the period 2005-10, resource need was accelerating faster than growth in financing.

Findings from two evaluations of GAVI’s support for Health Systems Strengthening (HSS) were published in 2009. An external evaluation by HLSP[19] found insufficient technical support provided to countries applying for GAVI grants, an under-performing Independent Review Committee (IRC), and weaknesses in GAVI’s monitoring of grant activities. The study also found that countries were using GAVI grants for ‘downstream’ short-term HSS fixes rather than ‘upstream’ and long-term structural reform. A study by John Snow, Inc praised the multi-year, flexible and country-driven characteristics of GAVI HSS grant funding and encouraged GAVI to continue this support. But also found weak M&E of grant activity, low Civil Society involvement in the HSS proposal development process, unclear proposal writing guidelines, and over-reliance by countries on established development partners for assistance in implementing health system reform.[20]

PEPFAR

A quantitative study by Stanford University in 2009 – The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief in Africa: An Evaluation of Outcomes – calculated a 10.5% reduction in the death rate in PEPFAR’s 12 focus countries, equating to 1.2 million lives saved at a cost of $2450 per death averted. In 2007, an evaluation of PEPFAR by the Institute of Medicine found that PEPFAR had made significant progress in reaching its targets for prevention, treatment and care but also reported that budget allocations "limit the Country Teams ability to harmonize PEPFARs activities with those of the partner government and other donors", and PEPFARs ABC (Abstinence, Be faithful, and correct and consistent Condom use) priorities "fragment the natural continuum of needs and services, often in ways that do not correspond with global standards".[21]

References

- ↑ Biesma R., Brugha R., Harmer A., Walsh A., Spicer N. and Walt G. The effects of global health initiatives on country health systems: a review of the evidence from HIV/AIDS control. Health Policy and Planning 2009 24(4): 239-252

- ↑ In May 2009, the Obama Administration announced that it would be launching a six-year aid programme called the Global Health Initiative with a commitment of $63bn.

- ↑ By way of comparison, UNAIDS' Unified Workplan 2010/11 has a budget of $US484m over the two-year period. Of this, $US136.4m (the interagency fund), is set aside to pay for country level activities and staff

- ↑ PEPFAR data: The Power of Partnership: Third Annual Report to Congress on PEPFAR, p210; Celebrating Life: 5th Annual Report to Congress Highlights brochure. Global Fund data: Global Fund pledges 2005-09; pledges for 2001-03 from the CRS Report for Congress: The Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria: Background and Current Issues; GLOBAL FUND OBSERVER (GFO) NEWSLETTER issue 39. World bank HIV/AIDS data: World bank Resources web page. GAVI data: GAVI total cash received from donors. Sources accessed 08/02/2010

- ↑ Bernstein M. and Sessions M. A Trickle or a Flood: Commitments and Disbursement for HIV/AIDS from the Global Fund, PEPFAR, and the World Bank's Multi-Country AIDS Program (MAP), 2007, Centre for Global Development; Oomman N., Bernstein M. and Rosenzweig S. Following the Funding for HIV/AIDS: A Comparative Analysis of the Funding Practices of PEPFAR, the Global Fund and World Bank MAP in Mozambique, Uganda and Zambia, 2007. Centre for Global Development[www.cgdev.org CGDEV]

- ↑ World Bank data: World Bank, HIV/AIDS data. PEPFAR data: World AIDS day 2009: Pepfar latest results. Global Fund data: Pledges and Contributions. GAVI data: Approved support (Aug 08 data). Sources accessed 08/02/10.

- ↑ For a comprehensive assessment of the limitations of evaluating GHIs see Section 1.3 Assessing Impact of ‘Final Report – Global Fund Five-Year Evaluation: Study Area 3: The Impact of Collective Efforts on the education of the Diseases Burden of AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria

- ↑ Section 2.1, Global Fund Five-Year Evaluation: Study Area 3: The Impact of Collective Efforts on the education of the Diseases Burden of AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria

- ↑ Farmer, Paul E., Bruce Nizeye, Sara Stulac, and Salmaan Keshavjee. 2006. Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine. PLoS Medicine, 1686-1691

- ↑ Bennett S. and Fairbank A, The system-wide effects of the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria: A conceptual framework, Oct 2003, Partners for Health Reformplus and Abt Associates Inc. Document summaries and links to each of the SWEF studies are accessible through the Global health Initiatives Network database

- ↑ Brugha et al (2005) Global Fund Tracking Study: A Cross-country Comparative Analysis, LSHTM, London. PDFs of each country study is accessible through the GHIN database

- ↑ Interactions between Global Health Initiatives and Health Systems: Evidence from Countries. The Maximising Positive Synergies Academic Consortium, June 2009, p6.

- ↑ World health Organisation Maximising Positive Synergies Collaborative Group, An assessment of interactions between global health initiatives and country health systems. Lancet 2009, 373:2137-69

- ↑ Brugha et al (2004) The Global Fund: Managing Great Expectations, Lancet, 364:95-100

- ↑ Global health Partnerships: Assessing Country Consequences, 2005, McKinsey and Co.

- ↑ Shakow A. Global Fund and world Bank HIV/AIDS Program: Comparative Advantage Study, 2006, Global Fund

- ↑ WHO Maximising Positive Synergies Collaborative Group. An assessment of interactions between global health initiatives and country health systems. The Lancet 373, June 20th pp2137-2169

- ↑ Chee G., Molldrem V., Hsi N. and Chankova S. (2008) Evaluation of the GAVI Phase 1 Performance. Abt Associates Inc. p15

- ↑ GAVI Health Systems Strengthening Support Evaluation: Key Findings and Recommendations

- ↑ Plowman B. and Abramson W. (2009) Final Synthesis Report - Health Systems Strengthening Tracking Study GAVI RFP00308. JSI Research and Training Institute, Inc. and In-Develop IPM.

- ↑ PEPFAR Implementation: Progress and Promise