Glenoid cavity

| Glenoid cavity | |

|---|---|

Costal surface of left scapula. Glenoid cavity shown in red. | |

Glenoid cavity shown in red. This cavity articulates with the head of the humerus. | |

| Details | |

| Latin | cavitas glenoidalis, fossa glenoidalis |

| Identifiers | |

| Gray's | p.207 |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | c_16/12220465 |

| TA | A02.4.01.019 |

| FMA | 23275 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

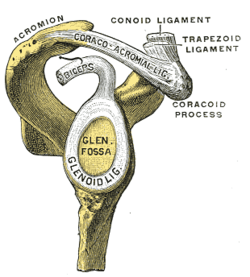

The glenoid cavity (or glenoid fossa of scapula from Greek: gléne, "socket") is a part of the shoulder. It is a shallow pyriform, articular surface, which is located on the lateral angle of the scapula. It is directed laterally and forward and articulates with the head of the humerus; it is broader below than above and its vertical diameter is the longest.

This cavity forms the glenohumeral joint along with the humerus. This type of joint is classified as a synovial, ball and socket joint. The humerus is held in place within the glenoid cavity by means of the long head of the bicep tendon. This tendon originates on the superior margin of the glenoid cavity and loops over the shoulder bracing humerus against the cavity. The rotator cuff also reinforces this joint more specifically with the supraspinatus tendon to hold the head of the humerus in the glenoid cavity.

The cavity surface is covered with cartilage in the fresh state; and its margins, slightly raised, give attachment to a fibrocartilaginous structure, the glenoid labrum, which deepens the cavity. This cartilage is very susceptible to tearing. When torn, it is most commonly known as a SLAP lesion which is generally caused by repetitive shoulder movements.

Compared to the acetabulum (hip-joint) the glenoid cavity is relatively shallow. This makes the shoulder joint prone to luxation. Strong ligaments and muscles prevents luxation in most cases.

By being so shallow the glenoid cavity allows the glenohumeral joint to have the greatest mobility of all joints in the body, allowing 120 degrees of unassisted flexion. This is also accomplished by the great mobility of the scapula (shoulder blade).

Evolution

Interpretations of the fossil remains of Australopithecus africanus (STS 7) and A. afarensis (AL 288-1; a.k.a. Lucy) suggest that the glenoid fossa was oriented more cranially in these species than in modern humans. This reflects the importance of overhead limb postures and suggests a retention of arboreal adaptations in these hominoid primates, whereas the lateral orientation of the glenoid in modern humans reflects the typical lowered position of the arm. [1]

In dinosaurs

In dinosaurs the main bones of the pectoral girdle were the scapula (shoulder blade) and the coracoid, both of which directly articulated with the clavicle. The place on the scapula where it articulated with the humerus (upper bone of the forelimb) is called the glenoid. The glenoid is important because it defines the range of motion of the humerus.[2]

Additional images

-

Left scapula. Glenoid cavity shown in red.

-

Animation. Glenoid cavity shown in red.

-

Same as the left. Humerus have been removed.

-

Glenoid fossa of right side.

-

Left scapula. Lateral view.

-

Left scapula. Lateral view. Glenoid cavity shown in red.

-

Anterior view of left Scapula showing Glenoid cavity "2"

-

Glenoid cavity of glenohumeral joint

-

Animation of glenohumeral joint. The muscles shown are subscapularis muscle (at right), infraspinatus muscle (at top left), teres minor muscle (at bottom left).

-

.gif)

Animation of glenohumeral joint. The muscle shown is supraspinatus muscle.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Larson 2009, p. 65

- ↑ Martin, A.J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. pg. 299-300. ISBN 1–4051–3413–5.

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

References

- Larson, Susan G. (2009). "Evolution of the Hominin Shoulder: Early Homo". In Grine, Frederick E.; Fleagle, John G.; Leakey, Richard E. The First Humans – Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9980-9. ISBN 978-1-4020-9979-3.

- ANATOMY & PHYSIOLOGY: THE UNITY OF FORM AND FUNCTION, SIXTH EDITION Published by McGraw-Hill Written by Kenneth Saladin

- http://www.ucsfhealth.org/conditions/glenoid_labrum_tear/index.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Glenoid cavity. |

- Diagram at cerrocoso.edu

- Anatomy figure: 03:02-07 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Glenoid+fossa at eMedicine Dictionary

- Mechanics of Glenohumeral Instability at University of Washington Department of Orthopaedics

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||