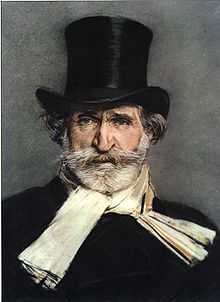

Giuseppe Verdi

|

"O sommo Carlo"

'Ernani (1844), act 3, sung by Mattia Battistini, Emilia Corsi, Luigi Colazza, Aristodemo Sillich, and the La Scala chorus in 1906 |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

|

Quartet "Bella figlia dell'amore"

Rigoletto (1851), act 3. A 1907 Victor Records recording with Enrico Caruso, Bessie Abott, Louise Homer and Antonio Scotti. |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

|

"È scherzo od è follia"

Un ballo in maschera (1859), act 1, scene 2. Performed by Enrico Caruso, Frieda Hempel, Maria Duchêne, Andrés de Segurola and Léon Rothier. "Nè gustare m'è dato un'ora..."

|

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

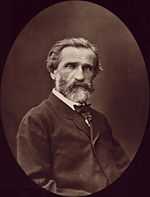

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (Italian: [d͡ʒuˈzɛppe ˈverdi]; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian Romantic composer primarily known for his operas.

He is considered, with Richard Wagner, the preëminent opera composer of the 19th century.[1] Verdi dominated the Italian opera scene after the eras of Bellini, Donizetti and Rossini. His works are frequently performed in opera houses throughout the world and, transcending the boundaries of the genre, some of his themes have long since taken root in popular culture, examples being "La donna è mobile" from Rigoletto, "Libiamo ne' lieti calici" (The Drinking Song) from La traviata, "Va, pensiero" (The Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves) from Nabucco, the "Coro di zingari" (Anvil Chorus) from Il trovatore and the "Grand March" from Aida.

Moved by the death of compatriot Alessandro Manzoni, Verdi wrote Messa da Requiem in 1874 in Manzoni's honour, a work now regarded as a masterpiece of the oratorio tradition and a testimony to his capacity outside the field of opera.[2] Visionary and politically engaged, he remains – alongside Garibaldi and Cavour – an emblematic figure of the reunification process (the Risorgimento) of the Italian Peninsula.

The early years: Le Roncole, Busseto and Milan

Verdi was born the son of Carlo Giuseppe Verdi (1785–1867) and Luigia Uttini (1787–1851) in Le Roncole, a village near Busseto, then in the Département Taro and within the borders of the First French Empire after the annexation of the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza.

The baptismal register, prepared on 11 October, lists his parents Carlo and Luigia as "innkeeper" and "spinner" respectively. Additionally, it lists Verdi as being "born yesterday", but since days were often considered to begin at sunset, this could have meant either 9 or 10 October. Today, his birthday is celebrated on 10 October, as certainly was the case of the bi-centennial in 2013. The next day, he was baptized in the Roman Catholic Church in Latin as Joseph Fortuninus Franciscus. The day after that (Tuesday), Verdi's father took his newborn the three miles to Busseto, where the baby was recorded as Joseph Fortunin François, the clerk writing in French. As biographer George Martin notes, "so it happened, that for the civil and temporal world, Verdi was born a Frenchman."[3]

When Verdi was almost three, his parents had a baby girl, Giuseppa. However she died in 1833. From the age of four, Verdi was given private lessons in Latin and Italian by the village schoolmaster, Baistrocchi, and at 6 he attended the local school. At the same time, it appears that he began to learn to play the organ, becoming more and more attracted to music that his parents finally provided him with a spinet. As one of the composer's significant biographers, Mary Jane Phillips-Matz notes, "Verdi's gift for music was apparent by then, even by 1820 or 1821.[4] This period also began his association with the local church, serving in the choir, being an altar boy for a while, and taken organ lessons. After schoolmaster Baistrocchi's death, Verdi became the official paid organist at the age of eight.[5]

1820 to 1832: Musical education in Busseto

In regard to Verdi's family background, musicologist Roger Parker points out that both of Verdi's parents "belonged to families of small landowners and traders, certainly not the illiterate peasants from which Verdi later liked to present himself as having emerged." Also, during this time, "Carlo Verdi was energetic in furthering his son's education...something which Verdi tended to hide in later life,"[6] and, later, Parker states that, during these early years in Busseto, "The picture emerges of youthful precocity eagerly nurtured by an ambitious father and of a sustained, sophisticated and elaborate formal education [but about which, later in life, Verdi would give] the impression of [having] a largely self-taught and obscure youth."[6]

In 1823, when he was 10, Verdi's parents arranged for the boy to attend school in Busseto, enrolling him in a Ginnasio—an upper school for boys—run by Don Pietro Seletti. He was looked after by Pietro Michiara and his musical family, while the parents remained in charge of the inn at Le Roncole. However, Verdi returned regularly to play the organ on Sundays, walking the several kilometres.[7] In Busseto, the future composer's education was greatly facilitated by visits to the large town library with its 10,000 volumes. At age 11 he began to train in Italian, Latin, the humanities, and rhetoric. By the time he was 12, Verdi began lessons with Ferdinando Provesi, maestro di cappella at San Bartolomeo, director of the municipal music school and co-director of the local Società Filarmonica (Philharmonic Society). It was with Provesi that Verdi was given his first lessons in composition and, beginning a year or two later, he was to write that "From the ages of 13 to 18 I wrote a motley assortment of pieces: marches for band by the hundred, perhaps as many little sinfonie that were used in church, in the theatre and at concerts, five or six concertos and sets of variations for pianoforte, which I played myself at concerts, many serenades, cantatas (arias, duets, very many trios) and various pieces of church music, of which I remember only a Stabat Mater".[8]

The other director of the Philharmonic Society was Antonio Barezzi , a 29-year-old wholesale grocer and distiller, who was described by a contemporary as a "manic dilettante" when it came to music [and who], as Phillips-Matz notes, "had mastered several instruments, among them the flute, clarinet, and ophicleide".[9] A regular member of the Philharmonic orchestra, Barezzi invited members to the spacious salon of his townhouse where they held rehearsals and performances. During those years, the Busseto Philharmonic was composed of 38 musicians, a considerable number of whom had been playing for over 15 years. They could also draw upon four tenors, two basses, a soprano or two, plus a full chorus.[10]

The young Verdi did not immediately become involved with the Philharmonic, so arduous were his other duties and the broad range of his studies. This resulted in some conflicts with his two principal teachers—Provesi for music and the priest Seletti at the Ginassio where he focused on academic studies, but by June 1827, he had completed the academic work, graduating with honours. After that time, he was able to focus solely on music under Provesi until June 1829. Fortuitously, when Verdi was 13, he was asked to step in as a replacement to play in what became his first public event in the town; he was an immediate success largely playing his own music to the surprise of many and it gave him immediate recognition in his home town.[9]

By 1829/30, Verdi had established himself as a major force in the Philharmonic: "no one of us could rival him" reported the Secretary of the organisation, Giuseppe Demaldė who was Barezzi's first cousin. His account of those times, Ceni biografici del Maestro Verdi appears in Phillips-Matz's biography.[9] Additionally, these years saw Verdi develop a lifelong interest in the writings of William Shakespeare (several of whose works he made into operas from 1847 forward); of Alessandro Manzoni whose I promesi sposi—a major work of Italian fiction—had a significant impact on the 16-year-old Verdi when he read it; and, thirdly, of the dramatist Vittorio Alfieri. Verdi would name his children Virginia and Icilio Romano after characters in Alfieri's tragedy Virginia.[11]

It was Alfieri's drama, Saul, which Verdi used as the basis of an eight-movement cantata called I deliri di Saul written at age 15 and performed in Bergamo to great acclaim, Demaldè noting: "The composition is a real jewel, a precious stone.." and Barezzi stating that it was "the first work of some significance...in which he shows a vivid imagination, a philosophical outlook, and sound judgment in the arrangement of instrumental parts".[12]

In late 1829, it become clear that Verdi needed to expand his musical horizons with either employment in some aspect of music or in further study. He had completed his studies with Provesi, who declared that he had no more to teach him, he was turned down for a local church organist's post, and he was planning to return to Le Roncole. It was at that point that Barezzi intervened, declaring "You are born for something better than that".[13]

The young man's increasingly close connection to the Barezzi family household had one other consequence. Born a few months before Verdi, the Barezzi's eldest daughter, Margherita, was becoming an accomplished singer and her father was beginning to look for opportunities for her to study in Milan. Verdi had been giving singing and piano lessons to Margherita and they spent time together playing and talking about music. But by 1830, Margherita's mother discovered that the young couple were in love. That further determined Antonio to have his daughter move away.

At the same time, Carlo Verdi, whose family business was in deep trouble, was exploring possibilities for his son to study music, and he made an application for funding to the Monte di Pietà e d'Abbondanza in Busseto, backed by strong references from Provesi and others. Verdi was invited to stay in the Barezzi household and settled in, continuing to help the Philharmonic with copying scores and all manner of related chores while all awaited news of the Pietà scholarship.

1832 to 1834: Musical education in Milan

(Litho by Alessandro Focosi, c.1840)

Verdi set his sights on Milan, then the cultural capital of northern Italy but, when the successful outcome of his application to the Monte di Pietà e d'Abbondanza was announced, he learned that he would have to wait until 1833 until funds were available. Fortunately, Barezzi recognized and wished to encourage the young man's talent and he guaranteed initial financial support for a year. Verdi, 18, set out for Milan in June 1832 accompanied by his father and Provesi.[14]

In Milan, where he stayed at the home of his former teacher, Seletti, he applied to study at the Conservatory, but after waiting for several days, he was rejected on several grounds. The Conservatory's reasoning was based on his limited piano technique (considered crucial by one teacher), his not being a resident of the Lombardy/Venetia region, and that he was older than the normal age to begin study there. Seletti wrote to Barezzi with the news and urging him to come to Milan, but Barezzi made arrangements for the young man to become a private pupil of Vincenzo Lavigna, paid for by him. Lavigna had been maestro concertatore at La Scala and he gave lessons in counterpoint along with a broader range of musical studies, with Verdi's classes beginning in July and his teacher describing his compositions as "very promising."[15] Verdi began attending operatic performances and concerts.

A year passed before the young man returned briefly to Busetto. News came of Provesi's death and Verdi's attitude towards his studies seemed to change as he enjoyed city life. He frequently attended La Scala and, for example during the 1834-35 season, he would have been able to see Giuditta Pasta as Norma and Maria Malibran in Rossini's Otello and La sonnambula among others, as well as works by Luigi Ricci, Gaetano Donizetti, and Saverio Mercadante.[16] Also, it was during this period that he attended the Salotto Maffei, Countess Clara Maffei's salons in Milan. Verdi became a lifelong friend and correspondent.

During his student days in Milan, Verdi had begun making connections in the world of music that were to stand him in good stead. As the composer told it—48 years later—in his 1879 An Autobiographical Sketch[17] written at Sant'Agata, these connections included an introduction by Lavigna to an amateur choral group, the Società Filarmonica, led by Pietro Massini, a man whom he described as: "if not very learned, was at least tenacious and patient: therefore just what was needed for a society of amateurs. They were organizing at the Teatro Filodrammatico the performance of an oratorio by Haydn, The Creation, [and] my teacher Lavigna asked me if, for my instruction, I wanted to follow the rehearsals, and I accepted with pleasure."[18]

Attending the Società frequently in 1834, Verdi soon found himself functioning as rehearsal director and continuo player for The Creation when, in the absence of all three rehearsal conductors, Massini asked Verdi to accompany a rehearsal, which he did with success. Verdi goes on to explain how Massini "proposed that I write an opera for the Teatro Filodrammatico....He sent me a libretto, which after being revised by Solera, became Oberto, Conte di Bonifacio".[18]

Returning briefly to Milan from Busseto in 1836, he conducted Rossini's La cenerentola[19] but many steps had to be taken before Oberto became a reality on the opera stage. In his 1879 "Sketch", Verdi supplied the anecdotes of how his first opera came about, but before that could begin to happen, he returned to Busseto for two-and-a-half years.

1834 to 1839: Return to Busseto

Carlo Verdi came to Milan to take the young man back home in mid-1834, saying he had to be in Busseto for the decision about who would succeed Provesi. However, rival factions in the town campaigned against him, and Verdi did not get the post. Later, however—with Barezzi's help—he did obtain the secular post of maestro di musica. He taught, gave lessons, and conducted the Philharmonic for several months before returning to Milan in early 1835.[20] In Milan, Barezzi again supported him, lodging him in an apartment with another of his protégés, Luigi Martelli. Verdi was expected to teach Martelli and continue to take lessons from Lavigna so he would become formally qualified for a teaching post. By July 1835, he obtained his certification from Lavigna, who stated that "I therefore believe him to be ready to practice his profession at the level of maestro di cappella."[21]

Verdi's first wife.

(La Scala Museum, Milan)

Back in Busseto, in 1835, the post of director of the music school remained unfilled. Verdi became its director with a three year contract. He married Margherita in May 1836, and by March 1837, she had given birth to their first child, Virginia Maria Luigia on 26 March 1837. Icilio Romano followed on 11 July 1838, but both died while Verdi was working on his first and second operas, Virginia on 12 August 1838 while the couple was still in Busseto and Ilicio on 22 October 1839 after the couple returned to Milan in February 1839.

Verdi took advantage of his connection to Pietro Massini, informing him in a series of letters from 1835 to 1837 about his progress in writing his first opera using Massini's libretto based on a work by Antonio Piazza, a Milanese "journalist and man of letters."[22] By then it had been given the title of Rocester and the young composer expressed hopes of a production at the Teatro Ducale in Parma with professional singers. Only when he encountered difficulties with that idea—the company appearing uninterested in a new work by an unknown composer—did he return to Massini in Milan. In subsequent letters, he continues to ask for Massini's assistance to stage the opera in Milan.[23]

Beginnings as an opera composer

1839 to 1840: Return to Milan; first opera, Oberto

Oberto (17 November 1839, La Scala, Milan). Whether Rocester actually became the basis for Oberto, when Verdi and Margherita returned to Milan in February 1839 after fulfilling two and a half years of his contract in Busseto, is subject to some disagreement among scholars. How much of Rocester remained visible in Oberto[24] is discussed by Roger Parker, who does suggest that "in this shape-shifting tendency, the opera was, of course, very much of its time."[25]

Impressario of La Scala

In his recollections in the 1879 "Sketch", Verdi describes how he was invited to meet the La Scala impresario, Bartolomeo Merelli, who had heard a conversation about the music of the opera between soprano Giuseppina Strepponi and Giorgio Ronconi in which she praised it. Merelli then offered to put on Oberto in November 1839, which was given a respectable 13 additional performances. After its success, Merelli offered Verdi a contract for three more works.[26]

Un giorno di regno (5 September 1840, La Scala, Milan). It was while he was working on his second opera, that Margherita died of encephalitis at age 26.[27][28] Verdi adored his wife and children and was devastated by their deaths, especially as the opera, a comedy, was given only a few months after his wife's death.

Un giorno was a flop and only given the one performance. Verdi acknowledged that the failure was partly due to his own personal circumstances[29] during the period leading up to and during its composition. A contributing factor was that the only singers the La Scala impresario had available were those assembled for an opera seria, Otto Nicolai's Il templario, and they had no experience with comedy: "The cast had been assembled chiefly for the performance of the season's most successful novelty, Il templario, Nicolai's version of Ivanhoe", notes Verdi scholar Julian Budden.[26] Other factors mentioned include the size of the La Scala house (noted by biographer George Martin as "too big for the piece") plus the rather old-fashioned nature of the work itself, which was written in a style that was rapidly going out of fashion.[30]

September 1840 to Autumn 1841: Verdi's year of despair, then Nabucco

(La Scala Museum)

Nabucco (9 March 1842, La Scala, Milan). After the failure of Giorno, Verdi vowed never to compose again, but in "An Autobiographical Sketch" written in 1879, he tells the story of how Merelli twice persuaded him to write a new opera.[31] However, the distance of 38 years may have led to a somewhat romanticized view (or, as Julian Budden puts it: "he was concerned to weave a protective legend about himself [since] it was all part of his fierce independence of spirit".)[32] But writing ten years closer to the time of event, Michele Lessona gives a very different version of the events after having been told the story by Verdi himself.[33]

Composer Otto Nicolai had rejected a libretto that Merelli offered him called Nabucodonosor by Temistocle Solera.[31] The impresario then gave a copy to Verdi hoping to interest the young composer in writing again. Verdi described how he took it home and threw "...it on the table with an almost violent gesture. ... In falling, it had opened of itself; without my realising it, my eyes clung to the open page and to one special line: 'Va pensiero, sull' ali dorate'."[18][34] Supposedly, Verdi continued to read it and he read and re-read the libretto three times, but others have said that he read the libretto very reluctantly[35] or, as recounted by Lessona, that he "threw the libretto in a corner without looking at it anymore, and for the next five months he carried on with his reading of bad novels...[when] towards the end of May he found himself with that blessed play in his hands: he read the last scene over again, the one with the death of Abigaille (which was later cut), seated himself almost mechanically at the piano ... and set the scene to music."[33][36] According to Verdi's account, he still refused to compose any music and took the manuscript back to the impresario the next day. Accepting no refusal, Merelli immediately stuffed the papers back into Verdi's pocket and—as Verdi recounts—"not only threw me out of his office, but slammed the door in my face and locked himself in."[18]

Verdi claims that he gradually began to work on the music: "This verse today, tomorrow that, here a note, there a whole phrase, and little by little the opera was written"[18] so that by the autumn of 1841 it was complete. Both Verdi's and Lessona's versions agree that a complete score of his third opera, which was initially known as Nabucodonosor but eventually, in 1844, both the title and name of the main character became Nabucco.[36]

First performed on 9 March 1842, Nabucodonosor's "public success in Milan was unprecedented",[37] dominating Donizetti's and Giovanni Pacini's operas playing nearby. While the public went mad with enthusiasm, the critics tempered their approval. Otto Nicolai, who had rejected the libretto, was enraged, but his opinions were in the minority. Nabucco assured Verdi's success until his retirement from the theatre, twenty-nine operas (including some revised and updated versions) later.

The "Galley Years" begin: Nabucco to La battaglia di Legnano

A period of hard work—producing twenty operas (excluding revisions and translations)—followed in the sixteen years after 1842, right up through the composition of Un ballo in maschera. Verdi described this period of his working life in the following way in a letter to Countess Clara Maffei in 1858:

- From Nabucco, you may say, I have never had one hour of peace. Sixteen years in the galleys.[38]

However, musicologist Philip Gossett notes that, while this was the composer's only written use of the expression,[39] he states that "[Verdi] laments the social circumstances in which Italian composers worked in the mid-nineteenth century, rather than judging aesthetic value.", a reference to the extraordinary output of operas written throughout Italy in the "primo ottocento" and staged under very short time-frames.[39]

This period was not without its frustrations and setbacks for the young composer. Along with other similar expressions of his feelings over the years, Verdi wrote to Giuseppe Demaldè, Barezzi's cousin Busseto, in April 1845 regarding I due Foscari 's reception, he stated:

- I am happy, no matter what reception it gets, and I am utterly indifferent to everything. I cannot wait for these next three years to pass. I have to write six operas, then addio to everything.[40]

Other letters around that same time stated that his was a career he abhorred.[40]

Musicologists and Verdi biographers typically divide the 54 years during which Verdi composed his operas into three periods: Early, Middle, and Late. The fourteen operas written in the Early years began with Oberto, and include I Lombardi in 1843, continuing through Ernani in 1844, Atilla in 1846, as well as his first adaptation of a Shakespeare play, Macbeth in 1847. Invited to compose for the Paris Opéra in 1847, Verdi revised and renamed I Lombardi to Jérusalem—and due to a number of Parisian conventions that had to be honored (including extensive ballets), it became Verdi's first work in the French grand opera style. This early period is typically regarded as ending with La battaglia di Legnano in January 1849. Scholar Martin Chusid then defines the "Middle Period" as starting with Luisa Miller in December 1849[41]

1842 to 1843: Verdi in Milan; new successes in Vienna, Parma and Venice

Temistocle Solera

Francesco Maria Piave

Act 1: The king steps from the cupboard to confront Ernani and Elvira

After the initial success of Nabucco, Verdi settled himself in Milan where he became surrounded by writers and artists, many of whom attended the salons of Countess Maffei. From that group, the young composer was drawn to Opprandino Arrivabene and to Giulio Carcano, the latter becoming significant to Verdi because of his translations of Shakespeare's plays into Italian, copies of which he forwarded to the young composer. By the 1870s, Carcano had published twelve volumes of the playwright's work. Many others members of the Maffei salon became Verdi's life-long friends.[42]

A revival of Nabucco followed in 1842 at La Scala where it received "a record run that still stands of fifty-seven performances",[43] and this led to a commission from Merelli for a new opera for the 1843 season. When it came to Verdi's fee, the impresario left that section of the contract blank, and it is known that the young composer consulted Giuseppina Strepponi as to what was appropriate. Her advice was not to charge any more than Bellini had received for his Norma, the sum being 8,000 Austrian lire, and this was acceptable to Merelli.[44]

I Lombardi alla prima crociata (11 February 1843, La Scala, Milan). The new opera would be based on a libretto by Temistocle Solera, who had written both of Verdi's first two operas. It drew upon the epic novel of the same name by Tommaso Grossi, incorporating its patriotic themes. The two men worked together from mid-March to mid-June 1842 for the first performance, to be given in February 1843.

Working with this librettist revealed a very early concern on the part of the young Verdi: he had firm notions of what he wanted dramatically, and what he wanted from his librettist—to the point that Verdi locked Solera in his room to force him to write the poetry the composer had in mind.[45] With the libretto completed by July, Verdi then spent the summer composing in Busseto, returning to Milan by the autumn where, in regard to the patriotic subject matter, some opposition came not from the Austrians but from the Church, although, in the end, only minor alterations were needed following Verdi's refusal to make any changes.[46] While the premiere performance was a very popular success (and it continued to be so after subsequent stagings everywhere), critical reactions were less enthusiastic. Inevitable comparisons were made with Nabucco. However, one writer noted: "If [Nabucco] created this young man's reputation, I Lombardi served to confirm it.".[47]

After the success of I Lombardi, in March 1843 Verdi set out for Vienna— to the city where Gaetano Donizetti was musical director—to oversee a production of Nabucco. The older composer, recognising Verdi's talent and that his own time as a successful composer was coming to an end, noted in a letter in January 1844 that "I am very, very happy to give way to people of talent like Verdi.....[Nothing] will prevent the good Verdi from soon reaching one of the most honourable positions in the cohort of composers."[48]

From Vienna in April, Verdi began to travel to Parma by way of Milan and Busseto. In the company of singers at the Teatro Regio di Parma was Giuseppina Strepponi. She had been ill for most of the previous year and had not sung since her last Abigaille in Milan, but she was a triumph at the opening performance of Nabucco given on 17 April and for the twenty performances that followed, all of which starred Strepponi in good voice. For Verdi himself, the performances were a personal triumph in his home area and his father, Carlo, attended the first performance.

Giuseppe remained in Parma for some weeks beyond his intended departure date. This fueled speculation that the delay was due to Strepponi's presence, emphasised by the fact that the couple had also been in Milan later in June and may have worked together in the late summer in Bologna on another successful production of Nabucco, which received 32 performances. Strepponi states that their relationship began in 1843.[49]

After successful stagings of Nabucco in Venice (with its twenty-five performances in the 1842—43 season), Verdi began negotiations with La Fenice impresario Count Alvise Mocenigo to stage I Lombardi in addition to writing a new opera for that house. Francesco Maria Piave was proposed as librettist. Before choosing a subject, the composer stuck firmly to his terms, especially those that involved his fee, and these proved acceptable. He explored many subjects, including I due Foscari (rejected due to the continued presence of that noble family in Venice). Finally, Victor Hugo's Hernani captured Verdi's imagination. Verdi accepted Piave as a librettist, even though he was relatively inexperienced. Piave began on a draft, which underwent many changes at the hands of the Venetian censors.

Ernani (9 March 1844, La Fenice, Venice). Verdi arrived in Venice on 1 December 1843 and work began with Piave, but before that occurred, the 26 December production of I Lombardi was, in Verdi's words, "one of the truly classic fiascos".[50] By late January, with a change of cast secured for the title role at Verdi's insistence and the score of Ernani ready for the copyists, Verdi heard that the La Fenice Secretary Giulielmo Brenna had reported that the copyists had described the work as being "a masterpiece".[51] As it turned out, chaos surrounded the final preparations for staging the opera: pieces of scenery and some costumes were missing, and the soprano, Sophie Löwe, was dissatisfied with her role. However, in spite of some limited quality singing, Ernani was well received on 9 March 1844, although with not as much enthusiasm as that received for the composer's two previous operas at their premieres. But on a personal level, Verdi triumphed with much of Venetian society as well as young intellectuals, poets, and journalists hosting him.

In spite of the experience of Venice, Verdi's work was to become his most popular opera until it was superseded by Il trovatore after 1853.

1844 to 1846: Busseto and Milan; Commissions from Rome, Milan, Naples, and Venice

The beginning of Verdi's and Muzio's years together

When Verdi returned to Milan on 13 April 1844, he took with him a young man, Emanuele Muzio, 8 years his junior, whom he had known since about 1828 and who was another of Antonio Barezzi's protégés.[52] Muzio was soon set up in a room opposite to where he lodged, and quickly the young man became indispensable to the composer, acting for him in a variety of ways to fulfill the contracts already in place for new operas in Rome, Milan, and Naples. At the same time, demands came for productions of Ernani in many other cities and, during this period, a new opera for Venice was offered.

As Muzio observed the 31-year-old composer, he saw a man who was, in Phillips-Matz' words, "generous, open, courteous, and surrounded by Milanese gentlemen who revered him. At times he became angry, impatient, or nervous; he was often ill [with "bouts of rheumatism, laryngitis, and neuralgia,"[53]] rarely free of pressure and always volatile"[54] and, at the same time, Muzio reported to Barezzi in April 1844, who had been an early supporter of that young man as well: "He, my Signor Maestro, has a breadth of spirit, of generosity, a wisdom, a heart that (to draw a comparison) one would have to set beside yours and say that they are the most generous hearts in the whole world."[55]

Their relationship was to grow stronger and stronger, and Muzio remained a life-long friend, supporting the composer and his work in every way possible. Only two years after his first letter, in November 1846, when he was being invited to compete for the post of maestro di musica in Busetto, Muzio gave an account of his life with Verdi and why he could never leave him:

- If you could see us, I seem more like a friend, rather than his pupil. We are always together at dinner, in the cafes, when we play cards...; all in all, he doesn't go anywhere without me at his side; in the house we have a big table and we both write there together, and so I always have his advice.[56]

Verdi's relationships with his librettists

Each new opera revealed Verdi's different relationships with his librettists. There was a return to Piave for I due Foscari for Rome in November 1844, then Temistocle Solera again for Giovanna d'Arco for La Scala in February 1845, while in August of that year the opportunity came to work with the pre-eminent librettist from Naples, Salvatore Cammarano, on Alzira for the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. Solera wrote most of Attila for La Fenice for March 1846, although this opera later involved Piave as well.

I due Foscari (3 November 1944, Rome). After Ernani, Verdi had considered a large number of projects for the future and Lord Byron's play, The Two Foscari was one of them. Writing to Piave in Venice, he suggested The Two Foscari, noting "I like the plot and the outline is already there in Venice".[57]

.jpg)

The operas was to become I due Foscari and Verdi encouraged Piave to work on it, stressing that "it's a fine subject, delicate and full of pathos".[58] As musicologist Roger Parker notes, it appears that Verdi was "concentrating on personal confrontations rather than grand scenic effects".[59] When Piave submitted the libretto, once again, the composer proposed changes in a long series of letters that revealed "...the extent to which Verdi intervened in the making of the libretto, a good deal of the large-scale structure of the opera being dictated by his increasingly exigent theatrical instincts."[59] With the music completed over the summer, I due Foscari was given its Rome premiere performance on 3 November 1844.

Giovanna d'Arco (15 February 1845, La Scala, Milan). With a libretto by Solera, this opera followed for La Scala in February 1845 and, while reasonably well received by audiences over its 17 performances, Verdi was unhappy with the way it had been staged and "with the deteriorating standards of Merelli's productions" overall.[35] In addition, due to Merelli's underhand negotiations to acquire the rights to the score from Ricordi, the composer vowed never again to deal with the impresario nor to set foot on the stage of La Scala.[60] In fact, the Milan house would have to wait for 36 years to stage another premiere of Verdi's work, the revised version of Simon Boccanegra.[61]

Alzira (12 August 1845, San Carlo, Naples). Following on the success of Ernani at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples, Verdi was invited to write an opera for that house.[62] One of the attractions for Verdi was that Salvadore Cammarano was the principal librettist in Italy

Salvadore Cammarano

and the Naples "house poet". Verdi laid out his terms to the management, which included a fee of one-third more than he had received for I Lombardi and, more importantly, requiring a finished libretto from Cammarano in his possession four months before the production. A synopsis for Alzira arrived from Cammarano[63] and Verdi appeared to adopt a somewhat passive attitude, impressed as he was at being able to work with this librettist[62] to whom he stated "It's not necessary for me to tell you to keep it short. You know the theatre better than I do."[63] It is quite clear that what was to become Verdi's characteristic requirement for brevity appeared this early in his career.

However, while still in Milan, another decline in Verdi's health, "with stomach trouble, severe headaches, and rheumatism",[64] kept him in bed and unable to compose for periods of time. This forced him to request a postponement until at least following August, with required medical certificates sent to back up the request. The San Carlo Intendant, Vincenzo Flaùto, attempted to persuade him to come anyway and received an annoyed reply from Verdi. However, he was well enough to spend the first twenty days of June composing, the trip beginning on 20 June, and he was well enough to oversee rehearsals when he arrived in the city.

In a letter of 30 July, he expressed optimism that the opera would be well received but notes that "if it were to fail, that wouldn't upset me unduly".[65] Attending a performance of I due Foscari at the San Carlo, Verdi received a very warm welcome both outside the house and from the audience,[66] but after a reasonably successful first performance, the others did not fare well and considerable attacks on the work and on its composer were published, one journalist proclaiming "No human talent is capable of producing two or three grand operas a year".[67] Later in his life Verdi was to refer to Alzira as proprio brutta ("downright ugly")[68] and he always regarded it as the worst of his operas.

Attila (17 March 1846, La Fenice, Venice). Zacharias Werner's ultra-Romantic German play, Attila, König der Hunnen, romantische Tragödie, was probably introduced to Verdi by Andrea Maffei who had written a synopsis.[35]

A letter to Francesco Maria Piave (with whom he had worked on both Ernani and I due Foscari) had included the subject of Attila as opera number 10 on a list of nine other possible projects,[69] and in that same letter, he encouraged Piave to read the play, which musicologist Julian Budden describes as having "sprung from the wilder shores of German literary romanticism [and which contains] all the Wagnerian apparatus - the Norns, Valhalla, the sword of Wodan [sic], the gods of light and the gods of darkness." He continues: "It is an extraordinary Teutonic farrago to have appealed to Verdi".[70] But, as this was to be the second opera Verdi would write for Venice, he appears to have changed his mind about working with Piave and convinced him to relinquish the project,[71] seemingly preferring to work with Solera as he had done on both of the two early operas, which employed the format of large choral tableaux—a feature the librettist wished to re-use for this new opera,[59] and, as Baldini speculates, in returning to Solera, Verdi was more comfortable working with a librettist who was more suited to "sketching epic sagas and historical-religious frescoes."[72] But, after writing two complete acts, Solera left the project altogether without informing anyone and followed his opera singer wife to Madrid,[72] leaving only the draft sketch of the third act. Solera's approach to the project had been to emphasize an appeal to Italian, specifically Venetian, patriotism.[71]

This obliged Verdi to returned to Piave for its completion, albeit done with Solera's blessing.[73] But the differences between each librettist's version were so great that it caused a final rift between Verdi and Solera, the composer's ideas of musical theatre having moved far ahead of that of his older colleague.

Seeking Piave's help in completing the opera, the pair met in Padua in December 1845 to work on the third act, but once again, illness forced Verdi to limit his work load. He was unable to oversee rehearsals of Giovanna d'Arco that month and remained in bed over Christmas for three weeks, although by 21 January he was able to get up in spite of his doctors stating that he needed to rest for six months. A relapse followed, and it was not until 24 February that he announced that, if the opera was to be finished, it would appear on the programme for only the last three or four evenings of the season.[74] Attila was first staged with limited success on its opening night but received a triumphal reception on the second and third nights.

1845: Verdi becomes a landowner

Upon his return to Busseto in April 1845, Verdi became a landowner by purchasing Il Pulgaro, 62 acres (23 hectares) of farmland with a farmhouse and outbuildings, near to where his parents lived. His parents began to live there from May 1844.[52]

Later, on 6 October 1845, with a first payment of 10,000 lire, he bought the Palazzo Cavalli (originally known as the Palazzo Dordoni and now known as the Palazzo Orlandi) on the via Roma, Busseto's main street. Encountering financial difficulties by the end of that year, Verdi asked his father for a loan. Carlo sold a field in Le Roncole for 1,000 lire, which was used to pay for some of the outstanding debt on Il Pulgaro, but—by May 1846—he was able to pay off the remaining loan of 4,000 lire on the Palazzo Cavalli.

It was when Verdi made the trip from Paris to Milan after the "Five Days" of March 1848 that he also visited Busseto to see his parents and Barezzi and, on 8 May, entered into a contract to acquire land and houses at Sant'Agata (which later became known as the Villa Verdi). As biographer George Martin observes:

- Whatever the reason for the purchase of the farm, it was not a whim. His purchase contract was complicated. It involved not only an exchange of properties (the Il Pulgaro farmland) but also required that Verdi guarantee certain mortgages that covered other lots that he was not interested in. From the first, however, he took a greater interest in the new property than he had in the old. The existing buildings on the new farm were in poor repair, and Verdi ordered them put in shape with some alterations and then hurried back to Milan.[75]

Payments were made by Carlo Verdi from loans he made to Giuseppe, and his parents then moved into the Palazzo Cavalli in May 1849.[76]

1846 to 1847: Milan, then Macbeth for Florence

Verdi's period of rest and recovery in Milan

The decline in Verdi's health while he was in Venice, an illness that had put him in real danger, caused him to return to Milan and postpone several future projects, including those he was beginning to plan for London and Paris. His health was still a worry to many, especially after rumours of his death had appeared in a Leipzig journal, and some were reprinted in Italy. Verdi spent about six months in Milan, as well as escaping some of the summer heat by going to Recoaro known for its mineral springs and from where he returned in much better health to begin work on Macbeth in September 1846. As work progressed, Muzio reported to Barezzi that "Verdi was working very, very slowly, but was well".[77] However, with worries over the production as a whole, problems with Piave's libretto, and the need to replace his indisposed Lady Macbeth, in December Verdi became ill again, but he continued to work on solving the problems facing his upcoming opera and appears to have been well enough when he left for Florence along with Muzio in mid-February.

Macbeth (14 March 1847, Teatro Pergola, Florence). Influenced by his friendship in the 1840s with Andrea Maffei, a poet and man of letters who had suggested both Schiller's Die Räuber (The Robbers) and Shakespeare's play Macbeth as suitable subjects for operas,[60] the composer received a commission from Florence's Teatro della Pergola with no particular opera specified.[78] Starting work on Macbeth, he knew of the availability of the baritone Felice Varesi, whom he wanted for the title role,[79] and, with Varesi under contract, Verdi could focus on the music for Macbeth.

Piave's text was based on a prose translation published in Turin in 1838, and Verdi did not encounter Shakespeare's original work until after the first performance of the opera, though he had read Shakespeare in translation for many years. In a 1865 letter to Piave he notes: "He is one of my favorite poets. I have had him in my hands from my earliest youth," and Verdi continues to make it clear how important this subject was to him: "....This tragedy is one of the greatest creations of man... If we can't make something great out of it let us at least try to do something out of the ordinary."[80]

But Verdi found that he needed to constantly bully Piave into correcting his drafts (so that Maffei had a hand in re-writing some scenes of the libretto, especially the witches' chorus in Act 3 and the sleepwalking scene),[81][82] their version follows Shakespeare's play quite closely, although it employs the three witches in the form of a large female chorus of witches, singing in three-part harmony.

Prior to Macbeth being performed, Verdi's Attila was given at the Pergola, rehearsed by Muzio. Many friends from Busseto arrived for the premiere as well as Strepponi who came from Paris. Macbeth's success on 14 March was magnificent, with the composer called out many times during the evening. The following performances were equally well received. In homage to his former father-in-law and long-time supporter, Antonio Barezzi, about two weeks after the premiere when he had returned to Milan Verdi dedicated the opera to him:

| “ | I have long intended to dedicate an opera to you, who have been father, benefactor, and friend to me. It was a duty I should have fulfilled sooner if imperious circumstances had not prevented me. Now, I send you Macbeth, which I prize above all my other operas, and therefore deem worthier to present to you.[83] | ” |

June 1847 to July 1849: Verdi in London and Paris

Operas for London, Paris, and Trieste

(Eduard Magnus, 1862)

I masnadieri (22 July 1847, Her Majesty's Theatre, London). Verdi left Italy at the end of May 1847, accompanied by his long-time assistant and student Emanuele Muzio. He has completed his work except for the orchestration, which he left until the opera was in rehearsal, since he wanted to hear "la Lind and modify her role to suit her more exactly."[84]

However, when the travelers reached Paris, rumours abounded that Lind would not be present and that she was not willing to learn new roles. Verdi then sent Muzio across the English Channel ahead of him, while he waited for an assurance that the soprano was in London. Muzio gave him that assurance, informing him that Lind was ready and eager. Verdi continued his journey and arrived in England on 5 June.[84][85]

Verdi agreed to conduct the premiere on 22 July 1847 as well as the second performance. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert attended the first performance, together with every member of the British aristocracy and fashionable society that were able to gain admission. Overall, the premiere was a triumphant success for the composer, and for the most part, the press was generous in its praise. After Verdi's departure, it was given twice more before the end of the season.[86]

.jpg)

Jérusalem (26 November 1847, The Opéra, Paris). Within a week of returning to Paris on 27 July 1847, Verdi received his first commission from the Académie Royale de Musique, as the Paris Opéra was officially known. Among 19th century Italian composers, there had been an increasing interest in writing for Paris, where the combination of money, prestige, and flexibility of style were appealing. Verdi agreed to adapt I Lombardi to a new French libretto by Alphonse Royer and Gustave Vaëz who had written the libretto for Donizetti's most successful French opera, La favorite.[87] The adaptation meant that Verdi could "try his hand at grand opera" without having to write something entirely new,[35] a strategy both Donizetti (with Les Martyrs in 1840) and Rossini (with Le siège de Corinthe in 1826) had employed for their Paris debuts.[59] The French version of I Lombardi changed locations and characters to French ones, and made significant changes to the structure of the work.

Il corsaro (25 October 1848, Teatro Grande in Trieste). Verdi had contracted with the Milanese publisher, Francesco Lucca for three operas. To satisfy the remaining commission, he proposed Corsaro, but was offered a counter proposal, which he rejected. From Paris in February 1848 Verdi sent the completed score to Lucca via Muzio, whom he had sent back to Milan to take care of business from there. Budden comments "In no other opera of his does Verdi appear to have taken so little interest before it was staged."[88] Where and when to stage it, and who the singers and stage director would be was left to the publisher. The composer took no further part in its premiere production, which was given only three performances at the Teatro Grande in Trieste.

Verdi's relationship with Giuseppina Strepponi

(date unknown)

Many writers, including Baldini and Frank Walker, have speculated on supposed relationships that Verdi—a man then in his thirties—might have had (or did have) with women in the years following his first wife's death. However, the only real evidence, visible in Walker's The Man Verdi[89] and Baldini's The Story of Giuseppe Verdi,[90] relates to Giuseppina Strepponi, the singer whom he first encountered at the time of composing Nabucco in 1842 and with whom he was involved professionally in revivals of that opera in the 1840s. These included those already noted in Parma in 1842, when he had remained in the city for some weeks beyond his intended departure date. As the couple had continued to see each other over the next year or so, Strepponi dates the beginning of their relationship to sometime in 1843.

As her voice declined and engagements dried up in the 1845 to 1846 period, she returned to live in Milan and was in contact with Verdi, continuing as his "supporter, promoter, unofficial adviser, and occasional secretary"[91] until she decided to retire and move to Paris in October 1846 where she set up a singing school for young gentlewomen in November (which was successful). Before she left for Paris, however, Verdi gave her a letter that pledged his love. On the envelope, Strepponi wrote "5 or 6 October 1846. They shall lay this letter on my heart when they bury me."[92]

With the help of Verdi's friends, the Escudiers, who lived in Paris, Strepponi began to promote her business and also planned a concert of Verdi's music for June 1847, coming out of her stage retirement briefly for one last opera appearance at the Comédie-Italienne, although it was not well received. But after Verdi returned from London to Paris in July 1847, the couple began a serious romantic relationship.

To friends in Italy, Verdi wrote that he wanted to "lead the life I wish," and that he "intended to stay a month in Paris, if I liked it,"[93] though he did not appear enthusiastic about the prospect.[93] However, with the exception of a return to Italy after the 18 March 1848 bloody uprising in Milan against the Austrians (when the composer was away from early April to mid-May) and the period of overseeing the rehearsals of La battaglia di Legnano in Rome (from before Christmas 1848 to early February 1849 after its premiere on 27 January 1849), Verdi remained in Paris for over two years.[94]

However, as the relationship with Strepponi proceeded, Verdi was known to be "living in an apartment around the corner from Strepponi's house," and that news had reached Italy ("Verdi had been seen chez Strepponi"),[95] In writing the music for Jérusalem, he had received her help to the extent that a handwritten love duet in the composer's autograph score contains alternative lines in her handwriting and in his, something described by British music critic Andrew Porter as "one of the more romantic discoveries of recent years."[96]

Baldini recounts that "at the end of 1847 Verdi rented a little house in Passy, and went to live there with Giuseppina",[97] but Phillips-Matz does not go so far, noting only that "he may have moved into her apartment or a separate apartment in her building."[98] However, later she does confirm the move to Passy, dating it to June 1848.[99] Also, at the end of 1847, Antonio Barezzi came to Paris and was entertained by Strepponi and Verdi, and in a letter from Busseto upon his return, he wrote glowingly of his time in that city.[100]

But, at this time it appears that, ultimately, Verdi would return to Italy as "he seemed to have no intention of cutting himself off from his home and his people."[101] He had intended to do so in early 1848, but work and illness prevented it, as most probably, did his increasing attachment to Strepponi. For her part, she seems to have intended to remain in France.

April 1848: Verdi and the Risorgimento

The "Cinque Giornate": Verdi hurries to Milan; then Busseto

During 1848 in Paris, Verdi was working with Salvadore Cammarano on two librettos, the first being one planned for Rome for a January 1849 premiere, but upon hearing the news of the "Cinque Giornate", the "Five Days" of street fighting that took place between 18 and 22 March 1848 and temporarily drove the Austrians out of Milan, Verdi quickly traveled to that city, arriving on 5 April.

There he found other returning emigres who were quickly caught up in celebrating the "triumph of popular passion over organised strength"[102] and who became involved in the political maneuverings. With all that, Phillips-Matz believes that Verdi's music had helped to feed the popular passion, with Attila standing out in particular.[102] However, musicologist Roger Parker feels that "during the entire time, there was virtually no mention of Verdi. The composer supposed to have inspired the masses to the barricades, the very artistic symbol of the Risorgimento, was somehow ignored in the press of events."[103]

In Milan, Verdi discovered that Piave was now "Citizen Piave" of the newly-proclaimed Republic of San Marco. Writing to him in Venice, Verdi proclaimed:

- Honor to these brave men! Honor to all Italy, which at this moment is truly great! Be assured, her hour of liberation has struck. It is the people that will it, and when the people will there is no absolute power that cart resist. They can do what they like, they can intrigue how they like, those that strive to impose themselves by brute force, but they will not succeed in defrauding the people of their rights. Yes, yes, a few more years, perhaps only a few more months, and Italy will be free, united and a republic. What else should she be?[57]

He concluded the letter to Piave with "Banish every petty municipal idea! We must all extend a fraternal hand, and Italy will yet become the first nation of the world" and exclaims "I am drunk with joy! Imagine that there are no more Germans here!![57]

However, as George Martin states:

- In Milan the political maneuvering among patriots of various political persuasions grew more complicated and bitter even as the war seemed to go better. But for those with a clear eye and good ear, like Mazzini and the Contessa Maffei in Milan, the political situation was alarming. Above the noise of the military bands and cheering crowds there was only the sound of argument, bitter and destructive, among the leaders of the various parties, states and towns.[104]

By the end of April, having spent time in Milan Verdi went on to Busseto to visit his parents and Barezzi. It was on 8 May that he acquired the house and land at Sant'Agata. By the middle of May he was back in Paris, gradually learning of the failure of attempts to secure a lasting hold on the Austrian lands following the Giornate. Muzio, who was forced to flee Venice, went first to Locarno and then gradually was able to make his way back towards Busseto after the Austrians re-took Milan on 5 August. He continued to be invaluable to Verdi.

January 1849: The "Early period" ends

La battaglia di Legnano (27 January 1849, Rome). Opera historian Charles Osborne describes La battaglia as "an opera with a purpose"

and maintains that "while parts of Verdi's earlier operas had frequently been taken up by the fighters of the Risorgimento [...] this time the composer had given the movement its own opera"[105] After he had composed Macbeth in 1847, Verdi had been admonished by the poet Giuseppe Giusti for turning away from patriotic subjects, the poet pleading with him to "do what you can to nourish the [sorrow of the Italian people], to strengthen it, and direct it to its goal."[106]

Verdi replied encouragingly, but even when his other obligations were out of the way, he was still hesitant to commit to anything that was not a genuinely patriotic subject until Salvadore Cammarano came up with the idea of adapting Joseph Méry's 1828 play La Bataille de Toulouse. It Italy at that time, this was a well-known and well-liked play, one that the librettist described as a story "that should stir every man with an Italian soul in his breast".[107] "Conceived in the springtime of Italian hopes" (as Budden described the initial enthusiasm for the work),[108] by the time Cammarano produced a final libretto it was early 1849. But by then, it was clear that the Austrians had not been permanently routed from Lombardy and that further effort would be required. The premiere was set for late January 1849.

To prepare the opera for staging, Verdi once again left Paris, travelling to Rome before the end of 1848. He found that city in turmoil. Pope Pius IX had fled to the south, and the city on was the verge of becoming a republic, which occurred within days of La battaglia's totally sold-out premiere at the Teatro Argentina. Adding to the events that accelerated Rome's passions was the opera's final chorus of freedom: Italia risorge vestita di Gloria, invitta e regina qual'era sarà / "Italy rises again robed in glory!, unconquered and a queen she shall be as once she was!"

July 1849: Verdi and Strepponi return to Italy

Verdi and Strepponi left Paris on 26 July 1849, the immediate cause being an outbreak of cholera but Walker proposes that it was also to do with the failure of France to act in defense of the many patriotic outbreaks in Italy and the couple's feeling that they could no longer remain.[109] Verdi went directly to Busseto to continue work on completing his latest opera, Luisa Miller, for a production in Naples later in the year[110] and Strepponi visited her family in Pavia and Florence from where, on 3 September, she wrote to Verdi to say that she would be leaving within a few days and that he should meet her in Parma and that he alone should then escort her to Busseto.[111]

In Verdi's home town, they lived in the "Palazzo Dordoni" (as it was then known, albeit that Verdi had purchased it from Contardo Cavalli and referred to it in that way. Eventually it became the Palazzo Orlandi),[112] the property in the centre of town which Verdi had acquired in October 1845.[113]

1849 to 1859: Verdi's "Middle Period"

The music of the "Middle Period"

Writing about the years 1849 to 1859, Verdi's "Middle Period", scholar Martin Chusid finds (and quotes from others) many distinguishing features in seven of the new operas of this period that sets them apart from those written both before and after.[41] Apart from Aroldo in 1857 (the extensive revision of the poorly-received Stiffelio of 1850), which has "little chance for operatic immortality",[41] all have entered the operatic repertory.[41] They begin with Luisa Miller in late 1849, continue through Stiffelio in 1850 to the great operas of the 1850s such as Rigoletto, Il trovatore and La traviata. Les vêpres siciliennes was a new work written specifically for Paris in 1855 (but is now more widely know in its Italian translation). The first version of Simon Boccanegra of 1857 (now more widely performed in its revised version from 1881) as well as Un ballo in maschera of 1859 brings the period to a close. Chusid's rationale for choosing Ballo as the ending date of this period is that the composer did not write for an Italian house until 1887 because he was in a position to accept only those commissions he wanted to work on and had time to thoroughly research.

Musically, David Kimbell states that, as the period began, in Luisa Miller and Stiffelio there appears to be a "growing freedom in the large scale structure...and an acute attention to fine detail."[114] Others echo those feelings. In contrast, regarding the post-1859 period, Chusid notes Strepponi's description of the 1860s and 1870s operas as being "modern" whereas Verdi described the pre-1849 works as "the cavatina operas",[115] meaning that "Verdi became increasingly dissatisfied with the older, familiar conventions of his predecessors that he had adopted at the outset of his career,"[115] reinforcing this view by noting that "most striking is Verdi's reduction in the number of cavatinas, limiting the number of choruses by 40 per cent compared to pre-1849 years (at the same time providing duets and other ensembles), and reducing the number of overtures in favour of shorter orchestral passages to introduce a scene.[116]

One example of Verdi's wish to move away from "standard forms" appears in his feelings about the structure of Il trovatore. To his librettist, Cammarano, Verdi plainly states that if there were no standard forms – "cavatinas, duets, trios, choruses, finales, etc. [....] and if you could avoid beginning with an opening chorus...."[117] he would be quite happy. In the case of this opera, we know that these wishes were not fulfilled.

Musicologist Julian Budden's conclusions about the impact made by Rigoletto and its place in Verdi's output during this period and beyond is summed up by his noting that:

- Just after 1850 at the age of 38, Verdi closed the door on a period of Italian opera with Rigoletto. The so-called ottocento in music is finished. Verdi will continue to draw on certain of its forms for the next few operas, but in a totally new spirit.[118]

July 1849 to May 1851: Verdi and Strepponi at the Palazzo Dordoni

While living openly in Busseto with Strepponi, Verdi completed work on Lusia Miller for Naples for the following December, traveling there with Barezzi in October to oversee the production. Also, he was committed to Ricordi for an opera—which became Stiffelio—for Trieste in the Spring of 1850 and, when that was over, he was preparing an acceptable libretto with Piave, engaged in negotiations with La Fenice, and then writing the music for Rigoletto for Venice for March 1851. Additionally, he began work on Il trovatore, which had he had to postpone for many months when he became preoccupied with family matters.

These matters included Verdi's concern over the reaction of many of the people of Busseto towards Giuseppina, a woman of the theatre living openly with the composer in an unmarried state. As such, she was shunned in the town and at church,[119] and while Verdi could "treat the Bussetani with contempt...Giuseppina, in the next few years, suffered greatly."[119] During this whole period "Verdi and Strepponi were wretchedly unhappy, offended by the neighbors' prying [and] they developed a siege mentality", notes Phillips-Matz[120] who continues by describing the situation of a woman of Giuseppina's theatrical background and with her accumulated illegitimate children as not being a prospect for marriage for anyone, "her conduct put[ting] her beyond the pale of bourgeois society of the time and was a matter of gossip even decades later."[120] Additionally, Verdi was concerned with the administration of his newly acquired property at Sant'Agata close to Busseto, where he had established his parents two years before,[121] and to where he began planning to move.

Separation from his parents; the complicating issue

The growing estrangement from his parents appears to have been brought about by what biographer Phillips-Matz describes as "Santa Streppini's (sic) mother got pregnant around the end of June 1850 or the beginning of July in 1850."[122] She infers that it was Strepponi who became pregnant, noting that the decline in the relationship began towards the end of 1850 because, if it had been Giuseppina who was pregnant, it would have become obvious by that time. In January 1851, the situation had become so bad that Verdi officially broke off his relationship with his parents, ordering the notary Balestra to prepare a document of legal separation from them, in which he gave Carlo and Luigia two months notice to leave Sant'Agata. Later, the illnesses of both his mother (who died in July 1851) and father, and the need to settle mutually-owed debts in the context of communication he had to conduct via Balestra revealed the depth of the decline. Finally, in April 1851, he reached agreement with the elder Verdis on the payment of mutually owed debts, and the couple were given two months to re-settle and ordered to leave Sant'Agata by April 1851. Verdi found a new home for them and helped them financially in getting settled.

Therefore, the issue of the pregnancy, which is based on evidence found in the Registro [degli] Eposti, 1848—1872, in the City of Cremona's archives, reveals that on 14 April 1851 "a baby girl was born to unidentified parents who had her delivered at nine-thirty that same night to the turnstile for abandoned babies at the Ospedale Maggiore in Cremona".[123] The child was identified as "Santa Streppini" (sic), which suggests to the biographer—based on evidence regarding Strepponi's pregnancies in the 1840s and the methods she employed to handle the newborns—that this could have been Strepponi's daughter, although she does also state that "there is a chance that she was born to a local woman to whom Strepponi lent her name".[123]

Associated with the possibility that "Santa Streppini" was Verdi's child is the effect that it might have had on the composer had he married Giuseppina at that point. However, it was Giuseppina, who—it appears—-was the one who rejected the idea of marriage during these years, not regarding herself as being worthy.[124] Had he married Strepponi during that time, Verdi would have been required to accept the responsibility for her children and it would have been almost impossible for any middle or upper-class father of a "turnstile child" (the esposti) to have recognised that child without bringing down the general hatred of society upon himself.[125] However, it is known who the foster parents of "Santa Streppini" were: they were a local family living very close to the Villa Verdi, suggesting in the biographer's mind that some sort of arrangement had been made in advance.[125]

May 1851 forward: Verdi and Strepponi at Sant'Agata

as it looked between 1859 and 1865

Verdi and Strepponi moved into the house on 1 May, a move Frank Walker sees as, "...a more and more complete withdrawal from society,"[126] albeit that Sant'Agata was only two miles away. As Phillips-Matz observes, Verdi actions—the issue of the possible pregnancy, the reaction to his living in a cohabiting state, the estrangement from his parents (itself not a good sign in 19th century Italian society)—cost him the respect of his community, as even those who were invited to the house from the town were shunned, the result being that the couple "became more and more isolated from the community."[127]

But Phillips-Matz concludes that, while there is no proof that the child, Santa Streppini, was Verdi's, the pregnancy "might have been the cause of the upheaval in Verdi's family life in 1850 and 1851, shattering long established, stable relationships and the leading the composer to cut himself off completely from his parents even as he became estranged from the Barezzis."[128]

Meanwhile, early in May, Strepponi had left for Florence, and was away for most of the month. May also brought an offer for a new opera from the La Fenice authorities, which Verdi eventually realised as La traviata. In turn, that was followed by an agreement with the Rome Opera company to present Il trovatore for January 1853.[129]

The summer and autumn of 1851 brought reports of the poor reception received from the stagings of Rigoletto firstly in Bergamo, and then again in Rome. Continuing to work on Il trovatore, negotiations were begun for an opera for Madrid, but those failed. The couple then decided to go to Paris for the winter, Strepponi was dispatched to see Ricordi in Milan to obtain a loan from him, and Muzio shut down the house for the winter on 11 December.

It was after they had been living in Paris for a few weeks that a stinging letter arrived from Barezzi, although its contents have not been preserved. What is known today is only Verdi's reply.

Deterioration of the relationship with Barezzi

Verdi's relationship with his father-in-law, Antonio Barezzi, had also deteriorated by the time the couple had moved to Sant'Agata. While Walker states that there was no breach between the two men,[130] there was a definite cooling off throughout 1851 and into 1852 when Verdi, then in Paris, received a letter from his Carissimo Suocero that appears to have criticised him for not being in Busseto over Christmas and New Year 1851. In his long reply, Verdi lays out some of his frustrations and objections to the way his actions appear to have been viewed in Busseto. While not blaming his benefactor, he writes that, "You live in a town that has the bad habit of often getting mixed up in other people's business, and disapproving of everything that does not conform to its ideas."[131]

However, Phillips-Matz notes that it seems possible, that for the entire time while the couple were living at the Palazzo Cavalli, she did not meet Barezzi nor his sons who are known to have visited, nor is it certain that she would have met either Piave and Muzio on their visits to Sant'Agata in the autumn 1851. Verdi continues his letter by stating that he likes his privacy and the freedom to administer his lands as he sees fit, but clearly states that "I have nothing to hide....[and] I have no difficulty whatever about telling you about my private life"[131] but he declares that neither Strepponi nor he has any obligation to reveal anything about their situation to anyone, and if the people of Busseto are not accepting of that "the loss of 20 or 30 thousand francs will never stop me from finding another patria somewhere else."[131] He concludes by offering his respects to Barezzi, to whom he states "I have always considered you and I consider you my benefactor, and I am honoured by that and I boast of it."[131]

November 1851 to March 1852: Verdi and Strepponi winter in Paris

By November, Verdi and Strepponi were able to leave Italy to spend the winter of 1851/52 in Paris, and for Stepponi, it was "a means of escape from the 'hole' (as she called the farm)".[132] For Verdi, he concluded an agreement with the Paris Opéra to write what became Les vêpres siciliennes, his first original grand opera for the stage. Also, he arranged, among other things, for a French translation of Macbeth. Work on Il trovatore and other projects consumed him, but a significant event occurred in February 1852, when the couple attended a performance of Alexander Dumas fils's play, The Lady of the Camellias. What followed is reported by Verdi's biographer, Mary Jane Phillips-Matz: the composer revealed that, after seeing the play, he immediately began to compose music for what would later become La traviata.[133]

The couple returned to Sant'Agata on 18 March 1852 and, after a year's delay, Verdi immediately began work on Il trovatore. In the background were his frustrations with dealing with Cammarano, but the librettist had inconveniently died before the libretto was completed. However, using a new and untried librettist, Bardare, Verdi took the opportunity to successfully re-work several elements of the opera. During his lifetime, Il trovatore came to be the most popular of all his works.

The relationship with Barezzi re-established; life at Sant'Agata continues

After the letter from Barezzi, which had reached Verdi in Paris and then after Verdi's reply, which actually revealed very little, upon the couple's return to Busseto in March 1852 there began a reconciliation with Barezzi and, with it, a greater connection between Giuseppina and her "Nonnon" and between Barezzi and "your most affectionate quasi-daughter" as she was to sign her letters to the older man.[134] Walker recounts an event later in the summer when Léon Escudier came from Paris to present Verdi with the Order of Chevalier of the Legion of Honour and he found Barezzi present at the dinner table. Escudier describes the older man's attitude towards the composer as "for Father Antonio, Verdi is a demi-god," and the dinner proceeded with Barezzi dominating the conversation and, finally, being allowed to take the award to show it off in the town.[135]

For Verdi, life at Sant'Agata continued and began to revolve around his land holdings, maintaining his control over his domain. After his visit to Rome for Il trovatore for January 1853, he worked on completing La traviata for March, but with little hope of its success on Verdi's part, due to his lack of confidence in any of the singers engaged for the season. These feelings he conveyed to Piave.[136] He was unwilling to take Strepponi with him (on this occasion, due as much to do with her poor health as anything else), but Verdi's trip to Venice became the last time that he refused to allow her to accompany him. Therefore, as commentators of the period relate, there was little correspondence between the couple; from then forward, they were together almost all the time.

The "Galley Years": operas from Luisa Miller to La traviata

Luisa Miller: (8 December 1849, Teatro San Carlo, Naples). This operas takes a distinctive turn away from subjects of the kind that preoccupied the Early Period. Music writer Charles Osborne compares this opera with Cammarano's previous libretto for La battaglia di Legnano and notes the contrasts between "the domesticity of the story as opposed to the larger, public nature of the earlier opera. Verdi's Luisa Miller, his first attempt at portraying something of bourgeois 'respectability' on the stage, is a direct predecessor of La traviata, which deals, amongst other things, with bourgeois hypocrisy."[137]

Gabriele Baldini makes a similar point when he comments that the opera "is in every sense a bourgeois tragedy [and] it feeds on the extraordinary fascination we have for everyday violent crimes. Nothing so far written by Verdi comes close to the concept of realism."[72] and he also notes the essentially "private" nature of the opera; before Luisa, "something had always been raging, striving beyond the limits of private interests."[72]

Stiffelio (16 November 1850, Teatro Grande, Trieste). Musicologist Roger Parker describes the opera as "A bold choice, a far cry from the melodramatic plots of Byron and Hugo: modern, 'realistic', subjects were unusual in Italian opera, and the religious subject matter seemed bound to cause problems with the censor. [...] The tendency of its most powerful moments to avoid or radically manipulate traditional structures has been much praised",[138] while Budden basically agrees, stating that "[Verdi] was tired of stock subjects; he wanted something with genuinely human, as distinct from melodramatic, interest. [....] Stiffelio had the attraction of being a problem play with a core of moral sensibility; the same attraction, in fact, that lead Verdi to La traviata a little later."[139]

Rigoletto (11 March 1851, La Fenice, Venice). While he was still laboring through his "years in the galleys", Verdi created one of his greatest masterpieces, which premiered in Venice in 1851. Based on a play by Victor Hugo (Le roi s'amuse), the libretto had to undergo substantial revisions to satisfy the epoch's censorship, and the composer was on the verge of giving it all up a number of times, but the opera quickly became a great success. Budden regards it as "revolutionary", just as Beethoven's Eroica Symphony was: "the barriers between formal melody and recitative are down as never before. In the whole opera, there is only one conventional double aria [...and there are...] no concerted act finales."[140] Verdi used that same word—"revolutionary"—in a letter to Piave,[141] and Budden also refers to a letter Verdi wrote in 1852 in which the composer states that "I conceived Rigoletto almost without arias, without finales but only an unending string of duets."[142]

Il trovatore (19 January 1853, Rome). Commissioned to produce the opera for Rome, Verdi left Strepponi in Livorno in late December 1852 and traveled by sea to Rome, readying himself for the final work on the opera, although he also worked on La traviata at the same time. For a while he was confined to his hotel by illness, but by premiere he was well and the premiere was a huge success. Offered a crown of laurel leaves at the end of the performance, Verdi took it home to give as a gift to Barezzi, "a tangible symbol of their reconciliation" notes Phillips-Matz, and he stayed on for the fourth performance as well: "A total triumph" reported Demaldè.[143]

La traviata (6 March 1853, La Fenice, Venice). Writing to Piave, he stated that "I don't want any of those everyday subjects that one can find by the hundreds"[144] and so it was agreed that the librettist would go to Sant'Agata and work with the composer. Within a short time, a synopsis was dispatched to Venice under the title of Amore e morte (Love and Death),[145] and described to his friend Cesare De Sanctis as "a subject for our own age,"[146] and one Verdi wished to see staged in modern dress. It quickly became clear that that would be impossible; instead it had to be set in the 17th century. The premiere was not well received—due largely to the unsuitable soprano in the main role: Verdi wrote to Muzio declaring it a fiasco and stating "La traviata last night a failure. Was the fault mine or the singers'? Time will tell."[147]

As the history of this opera has shown, it has become the most popular of all Verdi's operas, placing first in the list of most performed operas worldwide as reported on Operabase.[148]

1853 to 1859, the "Galley Years" come to an end

December 1855 to July 1856: Return to Sant'Agata

After all the ups and downs of the two years in Paris, Verdi was happy to return to Sant'Agata and, in February, was reporting to De Sanctis that [there has been a] "total abandonment of music; a little reading; some light occupation with agriculture and horses; that's all".[149] A couple of months later, writing in the same vein to Countess Maffei he stated: "I'm not doing anything. I don't read. I don't write. I walk in the fields from morning to evening, trying to recover, so far without success, from the stomach trouble caused me by I Vespri Siciliani. Cursed operas!"[150]

However, there was soon movement on the opera front: Piave came to Busseto to discuss creating Aroldo from Stiffelio, and on 15 May, Verdi signed a contract with La Fenice for an opera for the following spring. This was to be Simon Boccanegra.

July 1856 to January 1857: Paris again

The couple intended to stay in Paris for two weeks or so—and to be simply Mr. Verdi rather than Maestro Verdi—, but that did not turn out as planned.[151] The visit lasted until the following January and, while it included several personal matters such as selling furniture and disposing of the house there, it also became one involving operatic business. Firstly there was a failed attempt try to prevent the Théâtre-Italien from staging two of his operas; he worked on the revisions for Aroldo, sending material to Piave. By August, the source for Simon Boccanegra emerged, and a prose outline was shipped off to Piave. Then came the offer to stage the translated version of Il trovatore as a grand opera. This became Le trouvere at the Opéra on 12 January 1857. Verdi and Strepponi then returned to Sant'Agata.

1857: Return for a year of tranquil country life