Giuseppe Govone

Giuseppe Gaetano Maria Govone (Isola d'Asti, 1825 – Alba, Italy, January 1872) was an Italian general and politician of Piedmontese origin, who played a major role in the Italian Risorgimento.

An officer ahead of his time, he took part in the three Wars of Independence and distinguished himself as Minister of War in the government of Giovanni Lanza.

First Italian War of Independence

As a junior staff officer, First Lieutenant Giuseppe Govone took part in the battles of Pastrengo, Peschiera, and Cerlungo. Promoted to captain, he joined the staff of General Alfonso La Marmora's 6th Division.

In 1849, the 6th Division suppressed the republican Rebellion of Genoa, which broke out as a consequence of the Armistice of Vignale with Austria after the Battle of Novara. In this action, Govone was able without fighting to take control of three forts on the outskirts of Genoa.

For his actions in the First Italian War of Independence, Govone was awarded two Silver medals.

Crimean War

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1853–56 (Crimean War), Captain Govone played a decisive role in the defense of Silistria (May–June 1854). He drafted the plan for the inner redoubt of the city. The construction of this new redoubt prevented the Russians from taking Silistria immediately. Promoted to major, Govone took part in the famous Charge of the Light Brigade on October 25, 1854.

Second Italian War of Independence

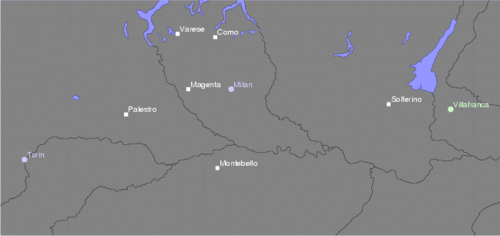

On the eve of the conflict, Govone was promoted to lieutenant colonel and assigned to the General Headquarters of the King and appointed Chief of the military intelligence unit (Ufficio I). In this position, he infiltrated Austrian lines on several occasions. He also fought in the Battle of Palestro, Battle of Magenta, and Battle of San Martino.

War Against the Brigandage in the Two Sicilies

« Questa è Africa! Altro che Italia! I beduini, a riscontro di questi cafoni, sono latte e miele.» / "This is Africa, not Italy! Compared to these rubes, the Bedouins are milk and honey."

(Luigi Carlo Farini, Lieutenant-Royal of Vittorio Emanuele II at Naples)

At the end of the Second War of Independence, Govone was promoted colonel at the age of 33 and, after a short marriage licence, sent to fight the brigandage in the Meridione of Italy. He operated in the Roveto and Liri valleys against the famous brigand Chiavone, the one amongst the many southern bandits who more resembled like a real bourbon legitimist partisan.

It was a hard and merciless battle, but devoid of the brutality that marked the conflict in other areas. Under Govone’s command was captured and then immediately executed by firing squad the carlist reactionary Spanish general José Borjes who had been chosen by Francis II of the Two Sicilies as one of the bourbon guerrilla general commanders while Chiavone was eventually sentenced to death by a court of his own traitorous lieutenants.

In Sicily

Promoted to brigadier general in 1861, Govone was transferred in 1862 to Sicily, where he used draconian measures to suppress widespread draft dodging, particularly in western Sicily. Under the provisions of the Pica Act (Legge Pica) of 1863, he imposed martial law, deploying 20 battalions of the elite corps of Italian Bersaglieri. He considered the mafiosi reactionary rebels against the government of the new united and liberal Kingdom of Italy and treated them accordingly. Towns and villages were surrounded and occupied by troops, water supplies were cut, and relatives of suspected draft dodgers were seized as hostages.[1]

It was an extremely critical phase: Facing the hostility of the population, Govone had made himself an enemy of the traditional Sicilian nobility and the rising mafia-linked middle class, who accused him of war crimes. In defending himself against these charges, Govone commented about the "barbarity" of Sicily and its inhabitants, sparking an uproar in the Italian parliament that led to a parliamentary investigation, resignations from the government, and challenges to duels among the deputies.[2] Cleared by the investigation, he was promoted to major general. Nonetheless, he was transferred to the mainland, returning to Sicily only to fight some duels.

Decorations

- Medaglia d'argento al valor militare — Cerlungo, 27 July 1848

- Medaglia d'argento al valor militare — Genoa, March 1849

- Ufficiale dell'Ordine Militare di Savoia — 2a Guerra d'Indipendenza, June 1859

- Grande Ufficiale dell'Ordine Militare di Savoia — 3a Guerra d'Indipendenza, 6 December 1866

- Grande Ufficiale dell'Ordine dei Santi Maurizio e Lazzaro

- Cavaliere dell'Ordine di Medjidie — Campagna del Danubio, 19 May 1854

- Cavaliere dell'Ordine del Bagno (Knight of The Most Honourable Order of the Bath) - Battaglia di Balaclava (Charge of the Light Brigade), 25 October 1854

- Ufficiale della Legion d'Onore (Officer of the Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur) - Battaglia della Cernaia (Battle of Chernaya River), 16 August 1855

- Medaglia commemorativa britannica di Crimea — tre fascette di Balaclava, Inkerman e Sebastopoli, 1855

- Medaglia commemorativa turca di Crimea

References

Sources

- Gioannini, Marco & Massobrio, Giulio: "Custoza 1866 : la via italiana alla sconfitta", Milano, Rizzoli, 2003 (Collana Storica Rizzoli) 392 p., 23 cm, ISBN 88-17-99507-X, EAN: 9788817995078

- GOVONE, Giuseppe: "Mémoires 1848-1870", Paris, Albert Fontemoing Editeur, 1905

- GOVONE, Uberto: "Il Generale Giuseppe Govone. Frammenti di Memorie", Torino, Fratelli Bocca Editori, 1920

- Quirico, Domenico: "Generali : controstoria dei vertici militari che fecero e disfecero l'Italia", Milano, Mondadori, c2006 (Le scie Mondadori), 411 p., 23 cm, ISBN 88-04-55330-8, EAN: 9788804553304

See also

- Brigandage in the Two Sicilies

- Royal Italian Army

|