Giorgio Ghisi

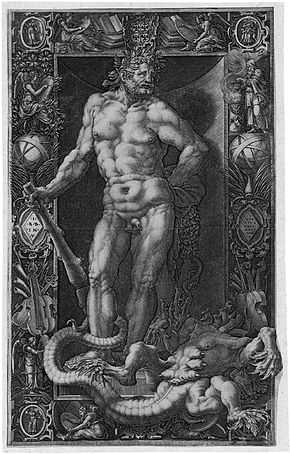

Giorgio Ghisi (1520 — 15 December 1582) was an Italian engraver from Mantua who also worked in Antwerp and in France. He made both prints and damascened metalwork, although only two surviving examples of the latter are known.

Life

He was the son of Lodovico Ghisi, a merchant whose family which had lived in Mantua for more than two hundred years. His artistic training is not documented, but he is thought to have learned engraving from Giovanni Battista Scultori.[1]

His earliest works are engravings after Giulio Romano, the dominant artistic figure in Mantua at the time. [1] At some time during pontificate of Paul III (1536–49) Ghisi visited Rome, where four of his prints were published by Antonio Lafreri. His other engravings from the 1540s included a large print, on ten separate plates, of Michelangelo's fresco of the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel. [1]

In 1549 or 1550 he went to Antwerp, where, between 1550 and 1555, he produced five dated engraving projects for Hieronymous Cock and Volcxken Diericx, the founders of Aux Quatre Vents, the largest print publisher in Northern Europe. The first of these, on two plates, was after Raphael's fresco The School of Athens, in 1550. It was followed by a copy of Lambert Lombard's Last Supper in 1551, Raphael's fresco Disputation of the Holy Sacrament in 1552, Agnolo Bronzino's The Nativity in 1553, and The Judgement of Paris, after Giovanni Battista Bertani in 1555.[2] In 1551 Ghisi joined the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke as a copperplate engraver, which was the same year the painters Ambrosius Bosschaert and Peter Breughel the Elder joined.[3]

One of only two surviving pieces of damascened armour known to have been engraved by him is also from this period, a shield signed and dated 1554.[4]

His movements between his employment with Cock and his return to Mantua in the late 1560s remain obscure; his engravings from this time were not commissioned by major publishers, although many seem to have been published in France, and Ghisi is known to have been in Paris in 1562.[4]

In the last few years of his life he was employed as keeper of jewels and precious metals, and overseer of the wardrobe, to the ruling family of Mantua, the Gonzagas. An inventory book, in Ghisi's own hand has entries dated between 15 December 1577 and 3 December 1582. The book includes some sketches of jewels, Ghisi's only known drawings.[5]

He died on 15 December 1582, aged 62. He was survived by his wife, but left no children.[5]

His brother Teodoro was a painter, and at least two of Ghisi's engravings are based on his designs. [6] Many older sources, misinterpreting a passage in Giorgio Vasaris's Lives of the Artists, mistakenly identify Giovanni Battista Scultori as his father, and Scultori's children, the engravers Adamo and Diana Scultori as his brother and sister, giving all three the surname "Ghisi".[6]

Prints

Ghisi was a reproductive engraver, that is one basing his works on paintings by other artists,[5] although he often elaborated backgrounds with landscapes of his own invention, and added lavish foliage.[7] Despite doing much of his work outside Italy, his models were almost always the works of Italian artists.[8] Ten are after Giulio Romano, and a total of 13 are by two painters working in France: Francesco Primaticcio and Luca Penti.".[8]

Metalwork

The two known pieces of metalwork engraved by Ghisi are a parade shield, dated 1554, and a sword hilt, dated 1570, now in Budapest. The shield, now part of the Waddesdon Bequest in the British Museum, is made of iron, hammered in relief, damascened with gold and partly plated with silver. It has an intricate design with a scene of battling horseman in the centre, within a frame, around which are four further frames containing allegorical female figures, the frames themselves incorporating minute subjects from the Iliad and ancient mythology, inlaid in gold.[9]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 The Engravings of Giorgio Ghisi, p. 16.

- ↑ The Engravings of Giorgio Ghisi, p. 17.

- ↑ Page 174-175 of the Liggeren

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 The Engravings of Giorgio Ghisi, p. 18.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 The Engravings of Giorgio Ghisi, p. 22.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The Engravings of Giorgio Ghisi, p. 15.

- ↑ The Engravings of Giorgio Ghisi, p. 23.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 The Engravings of Giorgio Ghisi, p. 25.

- ↑ "Demidoff Shield / Ghisi Shield". British Museum. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

Sources

- The Engravings of Giorgio Ghisi. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. (Free download available)

Further reading

- Boorsch, Suzanne (1984). The engravings of Giorgio Ghisi. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870993961.