Gilles de Rais

| Gilles de Rais | |

|---|---|

Gilles de Rais by Éloi Firmin Féron (1835) (artist's impression since no contemporary portrait has survived). | |

| Born |

prob. c. September 1405 Champtocé-sur-Loire, Anjou |

| Died |

26 October 1440 (aged 35) Nantes, Brittany |

Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Other names | The Original Bluebeard |

Criminal penalty | Death |

| Spouse(s) | Catherine de Thouars of Brittany (1420–1440) (his death) |

| Children | Marie (1429-1457) (left no progeny) |

| Parent(s) |

Guy II de Montmorency-Laval Marie de Craon |

| Killings | |

| Victims | 140 ? |

Span of killings | 1431–1440 |

Date apprehended | 15 September 1440 |

Gilles de Montmorency-Laval (prob. c. September 1405 – 26 October 1440),[1] Baron de Rais, was a knight and lord from Brittany, Anjou and Poitou,[2] a leader in the French army, and a companion-in-arms of Joan of Arc. He is best known for his reputation and later conviction as a presumed serial killer of children.

A member of the House of Montmorency-Laval, Gilles de Rais grew up under the tutelage of his maternal grandfather and increased his fortune by marriage. He earned the favour of the Duke of Brittany and was admitted to the French court. From 1427 to 1435, Gilles served as a commander in the Royal Army, and fought alongside Joan of Arc against the English and their Burgundian allies during the Hundred Years' War, for which he was appointed Marshal of France.

In 1434/1435, he retired from military life, depleted his wealth by staging an extravagant theatrical spectacle of his own composition, and was accused of dabbling in the occult. After 1432 Gilles was accused of engaging in a series of child murders, with victims possibly numbering in the hundreds. The killings came to an end in 1440, when a violent dispute with a clergyman led to an ecclesiastical investigation which brought the crimes to light, and attributed them to Gilles. At his trial the parents of missing children in the surrounding area and Gilles' own confederates in crime testified against him. Gilles was condemned to death and hanged at Nantes on 26 October 1440.

Gilles de Rais is believed to be the inspiration for the 1697 fairy tale "Bluebeard" ("Barbebleu") by Charles Perrault. His life is the subject of several modern novels, and referenced in a number of rock bands' albums and songs.

Early life

Gilles de Rais was probably born in late 1405[3] to Guy II de Montmorency-Laval and Marie de Craon in the family castle at Champtocé-sur-Loire.[4] He was an intelligent child, speaking fluent Latin, illuminating manuscripts, and dividing his education between military discipline and moral and intellectual development.[5][6] Following the deaths of his father and mother in 1415, Gilles and his younger brother René de La Suze were placed under the tutelage of Jean de Craon, their maternal grandfather.[7] Jean de Craon was a schemer who attempted to arrange a marriage for twelve-year-old Gilles with four-year-old Jeanne Paynel, one of the richest heiresses in Normandy, and, when the plan failed, attempted unsuccessfully to unite the boy with Béatrice de Rohan, the niece to the Duke of Brittany.[8] On 30 November 1420, however, Craon substantially increased his grandson's fortune by marrying him to Catherine de Thouars of Brittany, heiress of La Vendée and Poitou.[9] Their only child Marie was born in 1429.[10]

Military career

In the decades following the Breton War of Succession (1341–64), the defeated faction led by Olivier de Blois, Count of Penthièvre, continued to plot against the Dukes of the House of Montfort.[11] The Blois faction, who still refused to relinquish their claim to rule over the Duchy of Brittany, had taken Duke John VI prisoner in violation of the Treaty of Guérande (1365).[12] The sixteen-year-old Gilles took the side of the House of Montfort. Rais was able to secure the Duke's release, and was rewarded with generous land grants which were converted to monetary gifts.[13]

In 1425, Rais was introduced to the court of Charles VII at Saumur and learned courtly manners by studying the Dauphin.[14]

At the battle for the Château of Lude, he took prisoner the English captain Blackburn.[15][16]

From 1427 to 1435, Rais served as a commander in the Royal Army, distinguishing himself by displaying reckless bravery on the battlefield during the renewal of the Hundred Years War.[17] In 1429, he fought along with Joan of Arc in some of the campaigns waged against the English and their Burgundian allies.[18] He was present with Joan when the Siege of Orléans ended.[19]

On Sunday 17 July 1429, Gilles was chosen as one of four lords for the honor of bringing the Holy Ampulla from the Abbey of Saint-Remy to Notre-Dame de Reims for the consecration of Charles VII as King of France.[20] On the same day, he was officially created a Marshal of France.[18]

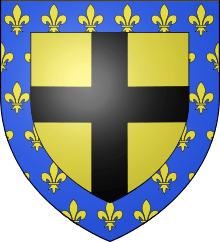

Following the Siege of Orléans, Rais was granted the right to add a border of the royal arms, the fleur-de-lys on an azure ground, to his own. The letters patent authorizing the display cited Gilles’ "high and commendable services", the "great perils and dangers" he had confronted, and "many other brave feats".[21]

In May 1431, Joan of Arc was burned at the stake; Gilles was not present. His grandfather died 15 November 1432, and, in a public gesture to mark his displeasure with Gilles' reckless spending of a carefully amassed fortune, left his sword and his breastplate to Gilles' younger brother René de La Suze.[22]

Private life

In 1434/5, Rais gradually withdrew from military and public life in order to pursue his own interests: the construction of a splendid Chapel of the Holy Innocents (where he officiated in robes of his own design),[23] and the production of a theatrical spectacle called Le Mistère du Siège d'Orléans. The play consisted of more than 20,000 lines of verse, requiring 140 speaking parts and 500 extras. Gilles was almost bankrupt at the time of the production and began selling property as early as 1432 to support his extravagant lifestyle. By March 1433, he had sold all his estates in Poitou (except those of his wife) and all his property in Maine. Only two castles in Anjou, Champtocé-sur-Loire and Ingrandes, remained in his possession. Half of the total sales and mortgages were spent on the production of his play. The spectacle was first performed in Orléans on 8 May 1435. Six hundred costumes were constructed, worn once, discarded, and constructed afresh for subsequent performances. Unlimited supplies of food and drink were made available to spectators at Gilles' expense.[24]

In June 1435, family members gathered to put a curb on Gilles. They appealed to Pope Eugene IV to disavow the Chapel of the Holy Innocents (which he refused to do) and carried their concerns to the king. On 2 July 1435, a royal edict was proclaimed in Orléans, Tours, Angers, Pouzauges, and Champtocé-sur-Loire denouncing Gilles as a spendthrift and forbidding him from selling any further property. No subject of Charles VII was allowed to enter into any contract with him, and those in command of his castles were forbidden to dispose of them. Gilles' credit fell immediately and his creditors pressed upon him. He borrowed heavily, using his objets d'art, manuscripts, books and clothing as security. When he left Orléans in late August or early September 1435, the town was littered with precious objects he was forced to leave behind. The edict did not apply to Brittany, and the family was unable to persuade the Duke of Brittany to enforce it.[25]

Occult involvement

In 1438, according to testimony at his trial from the priest Eustache Blanchet and the cleric François Prelati, de Rais sent out Blanchet to seek individuals who knew alchemy and demon summoning. Blanchet contacted Prelati in Florence and convinced him to take service with his master. Having reviewed the magical books of Prelati and a traveling Breton, de Rais chose to initiate experiments, the first taking place in the lower hall of his castle at Tiffauges, attempting to summon a demon named Barron. De Rais provided a contract with the demon for riches that Prelati was to give to the demon at a later time.

As no demon manifested after three tries, the Marshal grew frustrated with the lack of results. Prelati responded that the demon Barron was angry and required the offering of parts of a child. De Rais provided these remnants in a glass vessel at a future evocation. All of this was to no avail, and the occult experiments left him bitter and with his wealth severely depleted.[26]

Child killer

In his confession, Gilles maintained the first assaults on children occurred between spring 1432 and spring 1433.[27] The first murders occurred at Champtocé-sur-Loire; however, no account of these murders survived.[28] Shortly after, Gilles moved to Machecoul where, as the record of his confession states, he killed, or ordered to be killed, a great but uncertain number of children after he sodomized them.[28] Forty bodies were discovered in Machecoul in 1437.[28]

The first documented case of child-snatching and murder concerns a boy of twelve called Jeudon (first name unknown), an apprentice to the furrier Guillaume Hilairet.[29] Gilles de Rais' cousins, Gilles de Sillé and Roger de Briqueville, asked the furrier to lend them the boy to take a message to Machecoul, and, when Jeudon did not return, the two noblemen told the inquiring furrier that they were ignorant of the boy's whereabouts and suggested he had been carried off by thieves at Tiffauges to be made into a page.[29] In Gilles de Rais' trial, the events were testified to by Hillairet and his wife, the boy's father Jean Jeudon, and five others from Machecoul.

In his 1971 biography of Gilles de Rais, Jean Benedetti tells how the children who fell into Rais's hands were put to death:

[The boy] was pampered and dressed in better clothes than he had ever known. The evening began with a large meal and heavy drinking, particularly hippocras, which acted as a stimulant. The boy was then taken to an upper room to which only Gilles and his immediate circle were admitted. There he was confronted with the true nature of his situation. The shock thus produced on the boy was an initial source of pleasure for Gilles.[29]

Gilles' bodyservant Étienne Corrillaut, known as Poitou, was an accomplice in many of the crimes and testified that his master hung his victims with ropes from a hook to prevent the child from crying out, then masturbated upon the child's belly or thighs. Taking the victim down, Rais comforted the child and assured him he only wanted to play with him. Gilles then either killed the child himself or had the child killed by his cousin Gilles de Sillé, Poitou or another bodyservant called Henriet.[30] The victims were killed by decapitation, cutting of their throats, dismemberment, or breaking of their necks with a stick. A short, thick, double-edged sword called a braquemard was kept at hand for the murders.[30] Poitou further testified that Rais sometimes abused the victims (whether boys or girls) before wounding them and at other times after the victim had been slashed in the throat or decapitated. According to Poitou, Rais disdained the victim's sexual organs, and took "infinitely more pleasure in debauching himself in this manner ... than in using their natural orifice, in the normal manner."[30]

In his own confession, Gilles testified that “when the said children were dead, he kissed them and those who had the most handsome limbs and heads he held up to admire them, and had their bodies cruelly cut open and took delight at the sight of their inner organs; and very often when the children were dying he sat on their stomachs and took pleasure in seeing them die and laughed”.[31]

Poitou testified that he and Henriet burned the bodies in the fireplace in Gilles' room. The clothes of the victim were placed into the fire piece by piece so they burned slowly and the smell was minimized. The ashes were then thrown into the cesspit, the moat, or other hiding places.[31] The last recorded murder was of the son of Éonnet de Villeblanche and his wife Macée. Poitou paid 20 sous to have a page's doublet made for the victim, who was then assaulted, murdered, and incinerated in August 1440.[32]

Trial and execution

On 15 May 1440, Rais kidnapped a cleric during a dispute at the Church of Saint-Étienne-de-Mer-Morte.[33][34] The act prompted an investigation by the Bishop of Nantes, during which evidence of Gilles' crimes was uncovered.[33] On 29 July, the Bishop released his findings,[35] and subsequently obtained the prosecutorial cooperation of Rais's former protector, John VI, Duke of Brittany. Rais and his bodyservants Poitou and Henriet were arrested on 15 September 1440,[36][37] following a secular investigation which paralleled the findings of the investigation from the Bishop of Nantes. Rais's prosecution would likewise be conducted by both secular and ecclesiastical courts, on charges which included murder, sodomy, and heresy.[38]

The extensive witness testimony convinced the judges that there were adequate grounds for establishing the guilt of the accused. After Rais admitted to the charges on 21 October,[39] the court canceled a plan to torture him into confessing.[40] Peasants of the neighboring villages had earlier begun to make accusations that their children had entered Gilles' castle begging for food and had never been seen again. The transcript, which included testimony from the parents of many of these missing children as well as graphic descriptions of the murders provided by Gilles' accomplices, was said to be so lurid that the judges ordered the worst portions to be stricken from the record.

The precise number of Gilles' victims is not known, as most of the bodies were burned or buried. The number of murders is generally placed between 80 and 200; a few have conjectured numbers upwards of 600. The victims ranged in age from six to eighteen and included both sexes.

On 23 October 1440, the secular court heard the confessions of Poitou and Henriet and condemned them both to death,[41] followed by Gilles' death sentence on 25 October.[41] Gilles was allowed to make confession,[41] and his request to be buried in the church of the monastery of Notre-Dame des Carmes in Nantes was granted.[42]

Execution by hanging and burning was set for Wednesday 26 October. At nine o‘clock, Gilles and his two accomplices made their way in procession to the place of execution on the Ile de Biesse.[43] Gilles is said to have addressed the crowd with contrite piety and exhorted Henriet and Poitou to die bravely and think only of salvation.[42] Gilles' request to be the first to die had been granted the day before.[41] At eleven o'clock, the brush at the platform was set afire and Rais was hanged. His body was cut down before being consumed by the flames and claimed by "four ladies of high rank" for burial.[42][44] Henriet and Poitou were executed in similar fashion but their bodies were reduced to ashes in the flames and then scattered.[42][44][note 1][45]

Descendants and Barony of Rais

Marie de Rais {d.1457} married 1} Prigent VII de Coëtivy {1399-d.20 July 1450 Cherbourg, France}; married 2nd to André de Laval-Montmorency {1408-1486]; no children from either marriage; the Barony de Rais passed to René de Rais {1414-1473} an uncle of Marie De Rais. The barony passed to Rene's daughter Jeanne de Retz [1456-1473] married to Francois de Chauvigny {1430-1491}; their son was André III de Chauvigny {d.-1503} married Louise de Bourbon, Duchess of Montpensier {1482-1561}; no children. Louise de Bourbon, Duchess of Montpensier married Louis, Prince of La Roche-sur-Yon.

Question of guilt

Although Gilles de Rais was convicted of murdering many children by his confessions and the detailed eyewitness accounts of his own confederates and victims' parents,[46] doubts have persisted about the court's verdict. Counterarguments are based on the theory de Rais was himself a victim of an ecclesiastic plot or act of revenge by the Catholic Church or French state. Doubts on Gilles de Rais' guilt have long persisted because the Duke of Brittany, who was given the authority to prosecute, received all the titles to Gilles' former lands after his conviction. The Duke then divided the land among his own nobles. Writers such as secret societies specialist Jean-Pierre Bayard, in his book Plaidoyer pour Gilles de Rais, contend he was a victim of the Inquisition.

In the early 20th century, Anthropologist Margaret Murray and occultist Aleister Crowley are among those who questioned the involvement of the ecclesiastic and secular authorities in the case. Murray, who propagated the witch-cult hypothesis, speculated in her book The Witch-Cult in Western Europe that Gilles de Rais was really a witch and adherent of a fertility cult centered on the pagan goddess, Diana.[47][48] However, many historians reject Murray's theory.[49][50][51][52][53][54] Norman Cohn argues that her theory does not agree with what is known of Gilles' crimes and trial.[55][56] Historians do not regard Gilles as a martyr to a pre-Christian religion; other scholars tend to view him as a lapsed Catholic who descended into crime and depravity.[57][58][59]

Gilles was retried in a Moot court, an unofficial process of rehabilitation in his home country of France.[60][61] In 1992, Freemason Jean-Yves Goëau-Brissonnière, the Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of France, organized a court consisting of former French ministers, parliament members and UNESCO experts to re-examine the source material and evidence available at the medieval trial. The hearing, which concluded Gilles de Rais was not guilty of the crimes, was turned into a documentary called Gilles de Rais ou la Gueule du loup, narrated by the writer Gilbert Prouteau. A team of lawyers, writers and politicians led by Gilbert Prouteau and presided over by Judge Henri Juramy found him not guilty, although none of the initiators is a medieval historian by profession. In addition, none of them sought professional advice from certified medievalists.[62] "The case for Gilles de Rais's innocence is very strong," Prouteau said. "No child's corpse was ever found at his castle at Tiffauges and he appears to have confessed to escape excommunication...The accusations appear to be false charges made up by powerful rival lords to benefit from the confiscation of his lands.".[63] However, the journalist Gilbert Philippe from the newspaper Ouest-France, said that Prouteau was being "facetious and provocative".[64] He also claimed that Prouteau thought the retrial was basically "an absolute joke".[65]

Cultural references

Books, graphic novels

- The protagonist Durtal, from Huysmans's Là-bas (1891), conducts intensive research into Gilles de Rais which forms the basis of many of the chapters in the novel.

- Gilles de Rais is one of the antagonists in the popular manga Drifters.

- Gilles de Rais is the main of antagonists the manga Tetragrammaton Labyrinth. Angela, the protagonist of the manga, is revealed to be one of the young victims of Rais. Gilles de Rais ultimate goal is later revealed to be the revival of Jeanne d'Arc.

- "Classical Scenes of Farewell", a short story by Jim Shepard, is told from the point of view of one of Gilles de Rais' servants.

- Philip José Farmer's 1968 sf novel The Image of the Beast features a "she-creature who gives birth to the limbless, ectoplasmic simulacrum of satanic child killer Gilles de Rais".[66]

- In the science fiction novella "Rumfuddle" by Jack Vance, the main character, Gilbert Duray, is revealed at the end of the story to actually be Gilles de Rais, one of several notorious historical figures taken from their own times to be "rehabilitated" in alternate worlds.

- Gilles de Rais is a central character in the comic series Jhen Roque by Jacques Martin and Jean Pleyers. He appears at least in the following episodes 1-L’Or de la Mort, 2-Jehanne de France, 3-Les Ecorcheurs, 4-La Barbe Bleue, 5-La Cathedrale, 6-Le Lys et l’Ogre, 7-L’Alchimiste, 8-Le Secret des Templiers, 10-Les Sorcieres.[67] These books are published by Casterman.

- Gilles de Rais is a main character in the series "Joan of Arc Tapestries" by Ann Chamberlin. The first book, "The Merlin of St. Gille's Well" was published in 2000.

- Gilles de Rais's career with Joan of Arc and his subsequent decline and execution is a major plot point of H. Warner Munn's 1974 fantasy novel Merlin's Ring.

- Gilles de Rais is the subject of a 1977 novel by Edward Lucie-Smith titled "The Dark Pageant". The story is narrated by Raoul de Saumur, companion and comrade-in-arms to de Rais.

- Gilles de Rais makes a brief appearance in the 2012 novel, The Folly of the World, by Jesse Bullington.

- "Bluebeard Brave Warrior, Brutal Psychopath." Valerie Ogden. Palisades, New York. History Publishing Company

Film and television

- David Oxley played the part in Otto Preminger's 1957 film version of Shaw's play, Saint Joan.

- The 1974 film El Mariscal del Infierno (The Marshall from Hell, also known as Devil's Possessed) from director León Klimovsky is a fictionalized account of the occult life and downfall of Gilles de Rais. Paul Naschy plays the role of Gilles de Rais.[68]

- In 1987, the Spanish director Agusti Villaronga directed the film Tras El Cristal, with an original script based on the killings of Gilles de Rais.

- Vincent Cassel played the part in Luc Besson's The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc in 1999.

- Gilles de Rais is featured as one of the antagonists in the 2011 anime Fate/Zero, in the class of Caster.

- Gilles de Rais was an alias given to "Ray" an openly gay support character in the 7th episode of the 4th season of the animated series Archer. His name was listed as such and the title of "Child-Murderer" in this episode titled Live and Let Dine

- Gilles de Rais was featured as the main antagonist of the 2014 anime Rage of Bahamut.

Music

- Macabre, (Technical/Death Metal band from Chicago) released a song about Gilles de Rais called "The Black Knight" from the 2011 Grim Scary Tales album.

- Cradle of Filth's album Godspeed on the Devil's Thunder is centered on the life of Gilles de Rais after Joan of Arc's burning.

- La Passion de Gilles, opera (French libretto), 1983, music: Philippe Boesmans, libretto: Pierre Mertens based on his 1982 play (same title).

- The Black Dahlia Murder's song "The Window" on their Ritual album is based on Gilles de Rais, featuring lyrics such as "I sit upon their chests until they cease/Expressionless ejaculating whilst they die"

- Celtic Frost's debut album Morbid Tales had the song "Into the Crypt of Rays", a lyrical recounting of Rais' crimes and punishment.

- Brodequin's song "Gilles De Rais" from the album Festival of Death is also a lyrical recounting of Rais' crimes and execution.

- Ancient Rites' song "Morbid Glory (Gilles de Rais 1404–1440)" from the album "The Diabolical Serenades" is a lyrical recounting of Rais' crimes and execution.

References

Notes

- ↑ Several years after Gilles' death, his daughter Marie had a stone memorial erected at the site of his execution. Over the years, the structure came to be regarded as a holy altar under the protection of Saint Anne. Generations of pregnant women flocked there to pray for an abundance of breast milk. The memorial was destroyed by rioting Jacobins during the French Revolution in the late 18th century.

Footnotes

- ↑ (French) Matei Cazacu, Gilles de Rais, Paris: Tallandier, 2005, pp.11 ; pp.23-25

- ↑ (French) François Macé, Gilles de Rais, Nantes: Centre régional de documentation pédagogique de Nantes, 1988, pp.95-98.

- ↑ (French) Matei Cazacu, Gilles de Rais, Paris: Tallandier, 2005, p.11 ; 23-25.

- ↑ (French) Ambroise Ledru, "Gilles de Rais dit Barbe-Bleue, maréchal de France. Sa jeunesse, 1404-1424", L'union historique et littéraire du Maine, vol. I, 1893, pp.270-284; (French) Matei Cazacu, Gilles de Rais, 2005, p.11.

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, p. 33

- ↑ Wolf 1980, p. 13

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, p. 35

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, pp. 37–38

- ↑ Wolf 1980, p. 28

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, pp. 45,102

- ↑ Wolf 1980, pp. 22,24

- ↑ Wolf 1980, p. 23

- ↑ Wolf 1980, p. 26

- ↑ Wolf 1980, p. 37

- ↑ Jean de Bueil, Le Jouvencel, Paris, Librairie Renouard, Part 1, 1887, pp.XV-XVII ; Part 2 II, 1889, pp.273-275

- ↑ Matei Cazacu, Gilles de Rais, Taillandier, 2005, pp.79

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, pp. 63–64

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Benedetti 1971, p. 198

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, pp. 83–84

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, p. 93

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, p. 101

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, pp. 106,123

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, p. 123

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, pp. 128–133

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, p. 135

- ↑ Bataille, Georges. The Trial of Gilles de Rais. Los Angeles: AMOK, 1991.

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, p. 109

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Benedetti 1971, p. 112

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Benedetti 1971, p. 113

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Benedetti 1971, p. 114

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Benedetti 1971, p. 115

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, p. 171

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Benedetti 1971, p. 168

- ↑ Wolf 1980, p. 173

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, p. 169

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, pp. 176–177

- ↑ Wolf 1980, p. 178

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, pp. 177, 179

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, pp. 182–183

- ↑ Benedetti 1971, p. 184

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 Benedetti 1971, p. 189

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 Benedetti 1971, p. 190

- ↑ Wolf 1980, p. 213

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Wolf 1980, p. 215

- ↑ Wolf 1980, p. 223

- ↑ "Gilles de Rais: The Pious Monster". The Crime Library. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ↑ Murray, Margaret (1921). The Witch-Cult in Western Europe. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 173–174.

Gilles de Rais was tried and executed as a witch and, in the same way, much that is mysterious in this trial can also be explained by the Dianic Cult

- ↑ "Historical Association for Joan of Arc Studies."

- ↑ Trevor-Roper, Hugh. The European Witch-craze of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, 1969.

- ↑ Russell, Jeffrey. A History of Witchcraft: Sorcerers, Heretics, and Pagans, 1970.

- ↑ Simpson, Jacqueline. "Margaret Murray: Who Believed Her and Why?" Folkrealllore 105, 1994, pp. 89–96.

- ↑ Hutton, Ronald. The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1991.

- ↑ Hutton, Ronald. The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999

- ↑ Kitteredge, G. L. Witchcraft in Old and New England. 1951. pp. 275, 421, 565.

- ↑ Cohn, Norman. Europe's Inner Demons. London: Pimlico, 1973.

- ↑ Thomas, Keith. Religion and the Decline of Magic, 1971 and 1997, pp. 514–517.

- ↑ Barett, W.P. The Trial of Joan of Arc. 1932.

- ↑ Pernoud, Regine and Marie Veronique Clin. Joan of Arc, Her Story. 1966

- ↑ Meltzer, Françoise. For Fear of the Fire: Joan of Arc and the Limits of Subjectivity. 2001.

- ↑ Alain Jost, Gilles de Rais, Marabout, 1995, pp. 152

- ↑ http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1817&dat=19921111&id=ATkdAAAAIBAJ&sjid=5KUEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6620,2828943

- ↑ Jean Kerhervé, « L'histoire ou le roman ? », in Le Peuple breton, n° 347, November 1992, pp. 6-8

- ↑ http://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2013/jun/17/bluebeard-gilles-de-rais-france

- ↑ Gilbert Philippe, « L'écrivain Gilbert Prouteau s'est éteint à 95 ans - Vendée », in Ouest-France, Friday August 2012.

- ↑ Jean de Raigniac, book review of Gilbert Prouteau's Roman de la Vendée, in Lire en Vendée, June–December 2010, pp.5

- ↑ Philip José Farmer. The Image of the Beast. Creation Oneiros, 2007. ISBN 1 902197-24-0

- ↑ Marie-Madeleine Castellani, « Les figures du Mal dans la bande dessinée Jhen », Cahiers de recherches médiévales [En ligne], 2 | 1996, mis en ligne le 04 février 2008, consulté le 28 décembre 2013. URL : http://crm.revues.org/2502 ; DOI : 10.4000/crm.2502

- ↑

Bibliography

Historical studies and literary scholarship

- Georges Bataille, The Trial of Gilles de Rais, Los Angeles (California): Amok Books, ISBN 978-1-878923-02-8.

- (French) Eugène Bossard, Gilles de Rais, maréchal de France, dit "Barbe-Bleue", 1404-1440 : d'après des documents inédits, Paris: Honoré Champion, 1886, XIX-426-CLXVIII p., https://archive.org/stream/gillesderaismar00bossgoog#page/n11/mode/2up

- (French) Arthur Bourdeaut, "Chantocé, Gilles de Rays et les ducs de Bretagne", in Mémoires de la Société d'histoire et d'archéologie de Bretagne, Rennes: Société d'histoire et d'archéologie de Bretagne, t. V, 1924, pp. 41–150, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k4413300/f41.image.r

- (French) Pierre Boutin, Pierre Chalumeau, François Macé et Georges Peyronnet, Gilles de Rais, Nantes: Centre national de documentation pédagogique (CNDP) / Centre régional de documentation pédagogique (CRDP) de l'Académie de Nantes, 1988, 158 p. ISBN 2-86628-074-1

- (French) Olivier Bouzy, "La réhabilitation de Gilles de Rais, canular ou trucage ?", in Connaissance de Jeanne d'Arc, n° 22, 1993, pp. 17–25, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k58316056/f17.image.r

- (French) Olivier Bouzy, "Le Procès de Gilles de Rais. Preuve juridique et "exemplum"", in Connaissance de Jeanne d'Arc, n°26, janvier 1997, pp. 40-45, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5831681k/f40.image.r

- (French) Matei Cazacu, Gilles de Rais, Paris: Tallandier, 2005, 384 pp., ISBN 2-84734-227-3. (Italian) Matei Cazacu, Barbablù. Storia di Gilles de Rais, Mondadori, 2008, ISBN 978-8804581819.

- (French) Jacques Chiffoleau, "Gilles de Rais, ogre ou serial killer ?", in L'Histoire, n°335, octobre 2008, pp. 8–16.

- Emile Gabory, Alias Bluebeard The Life And Death of Gilles De Raiz. New York: Brewer & Warner Inc., 1930, 315 pp.

- (French) Michel Meurger, Gilles de Rais et la littérature, Rennes: Terre de brume, coll. "Terres fantastiques", 2003, 237 pp., ISBN 2-84362-149-6.

- Val Morgan, The Legend of Gilles de Rais (1404-1440) in the Writings of Huysmans, Bataille, Planchon, and Tournier, Lewiston (New York): Edwin Mellen Press, coll. "Studies in French Civilization" (n° 29), 2003, XVI-274 pp., ISBN 0-7734-6619-3.

- Ben Parsons, "Sympathy for the Devil : Gilles de Rais and His Modern Apologists", in Fifteenth-Century Studies / edited by Barbara I. Gusick and Matthew Z. Heintzelman, Rochester, New York / Woodbridge, Suffolk, Camden House / Boydell & Brewer, vol. 37, 2012, pp. 113–137, ISBN 978-1-57113-526-1.

- (French) Noël Valois, "Le procès de Gilles de Rais", in Annuaire-bulletin de la Société de l'histoire de France, Paris: Librairie Renouard, t. LIX, 1912, pp. 193–239, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k12298r/f3.image

Literature

- Benedetti, Jean (1971), Gilles de Rais, New York: Stein and Day, ISBN 978-0-8128-1450-7

- Wolf, Leonard (1980), Bluebeard: The Life and Times of Gilles De Rais, New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., ISBN 978-0-517-54061-9

- Georges Bordonove, Gilles de Rais, Pygmalion, ISBN 978-2-85704-694-3.

- (Spanish) Juan Antonio Cebrián, El Mariscal de las Tinieblas. La Verdadera Historia de Barba Azul, Temas de Hoy, ISBN 978-84-8460-497-6.

- Joris-Karl Huysmans, Down There or The Damned (Là-Bas), Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-22837-2.

- Reginald Hyatte, Laughter for the Devil: The Trials of Gilles De Rais, Companion-In-Arms of Joan of Arc (1440), Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, ISBN 978-0-8386-3190-4.

- Hubert Lampo, De duivel en de maagd, 207 p., Amsterdam, Meulenhoff, 1988 (11e druk), ISBN 90-290-0445-2. (1e druk: ’s-Gravenhage, Stols, 1955). (French) Le Diable et la Pucelle. 163 p., Presses universitaires du Septentrion, 2002, ISBN 2-85939-765-5.

- Robert Nye, The Life and Death of My Lord, Gilles de Rais. Time Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-349-10250-4.

External links

Media related to Gilles de Rais at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gilles de Rais at Wikimedia Commons

|