Giles Milton

| Giles Milton | |

|---|---|

| Born |

15 January 1966 Buckinghamshire |

| Occupation | Writer and Historian |

| Nationality | British |

| Children | Three daughters |

Giles Milton (born 15 January 1966) is a writer who specialises in the history of exploration. His books have been published in seventeen languages worldwide and are international best-sellers. He has written eight works of non-fiction, two comic novels and two books for young children.

He is best known for his 1999 best-selling title, Nathaniel's Nutmeg, a historical account of the violent struggle between the English and Dutch for control of the world supply of nutmeg in the early 17th century. The book was serialised by BBC Radio 4.[1] Nathaniel's Nutmeg was followed by Big Chief Elizabeth, Samurai William and White Gold, books of narrative non-fiction that took as their subject matter the pioneering English adventurers in Asia, North Africa and the New World, and then by his 2008, Paradise Lost, Smyrna 1922: The Destruction of Islam's City of Tolerance, which investigated the bloody sacking of Smyrna in September 1922, and the subsequent expulsion of 1,300,000 Orthodox Greeks from Turkey and 350,000 Muslims from Greece. His latest book, Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot was published in the summer of 2013 in the UK and in April, 2014 in North America.

Milton is the author of a weekly history blog that focuses on forgotten characters from the past.[2]

Biography

Born in Buckinghamshire, Milton was educated at Latymer Upper School and the University of Bristol. He lives in London and Burgundy and is married to the artist and illustrator, Alexandra Milton. He has three daughters.

Interests and influences

The author's early non-fiction titles display a particular interest in the lesser known adventurers of the 16th and 17th centuries, and the ill-treatment of indigenous populations as the first English merchants and traders moved into newly colonized lands. More recent titles have been concerned with 20th century history.

The books draw on unpublished source material – diaries, journals and private letters – as well as archival documentation kept by the East India Company and now housed in the British Library. He also cites contemporary published accounts, notably the 1589 anthology, The Principall Navigations, Voiages, and Discoveries of the English Nation by Richard Hakluyt and Purchas, his Pilgrimage; or, Relations of the World and the Religions observed in all Ages, 1613, by Samuel Purchas. In researching his 2008 work, Paradise Lost, Smyrna 1922, he collected an extensive archive of unpublished diaries and private letters written by the Levantines of Smyrna.[3]

His most recent title, Russian Roulette is an account of a small group of British spies smuggled into Moscow, Petrograd and Tashkent in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution. It is drawn from previously unpublished sources held in the archives of Indian Political Intelligence.

Works

Non-fiction

- The Riddle and the Knight: In Search of Sir John Mandeville, 1996

- Nathaniel's Nutmeg: How One Man's Courage Changed the Course of History, 1999

- Big Chief Elizabeth: The Adventures and Fate of the First English Colonists in America, 2000

- Samurai William: The Englishman Who Opened Japan, 2002

- White Gold: The Extraordinary Story of Thomas Pellow and North Africa's One Million European Slaves, 2005, Sceptre, ISBN 978-0-340-79469-2

- Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922, 2008, Sceptre, ISBN 978-0-340-83786-3

- Wolfram: The Boy Who Went To War, 2011, Sceptre, ISBN 978-0-340-83788-7

- Russian Roulette: A Deadly Game: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot, 2013, Sceptre, ISBN 978-1-444-73702-8

- When Hitler Took Cocaine: Fascinating Footnotes from History, John Murray. To be published September 2014

- When Stalin Robbed a Bank: Fascinating Footnotes from History, John Murray. To be published November 2014

Novels

- Edward Trencom's Nose: A Novel of History, Dark Intrigue, and Cheese, 2007

- According to Arnold: A Novel of Love and Mushrooms, 2009

- The Perfect Corpse, September 2014, Prospero Press, ISBN 978-0-992-8972-2-2

Children's books

- Call Me Gorgeous, 2009, Alexandra Milton, illustrator.

- Zebedee's Zoo, 2009, Kathleen McEwen, illustrator.

- Good Luck Baby Owls, 2012, Alexandra Milton, illustrator.

- Children of the Wild, 2013.

Russian Roulette

Russian Roulette is Giles Milton's eighth work of narrative history.

It is an historical account of a small group of British spies smuggled into Soviet Russia in the aftermath of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution. The spies were sent to Russia by Mansfield Cumming, the first director of the Secret Intelligence Service. The aim was to thwart Lenin’s Bolshevik-Islamic plot to topple British India and, ultimately, the Western democracies.

The spies included Sidney Reilly, Arthur Ransome, George Hill, Somerset Maugham, Paul Dukes and Augustus Agar. They worked undercover and in disguise, operating out of Moscow and Petrograd.

A second group of British agents was simultaneously sent into Central Asia (notably Tashkent and Kashgar). Frederick Bailey, Percy Etherton and Wilfrid Malleson were employed by Indian Political Intelligence, a body working closely with the Secret Intelligence Service.

In the period between 1918 and 1921 the spies in Moscow infiltrated Soviet commissariats, the Red Army and Cheka (secret police). They were variously involved in murder, deception and duplicity and, together with the British diplomat Robert Bruce Lockhart, were also implicated in a botched attempt to assassinate Lenin.

The spies in Tashkent and Kashgar saw themselves as playing the final chapter of the Great Game, the struggle for political mastery of Central Asia. Milton argues that the greatest achievement of these two groups of spies was to infiltrate the Comintern and unpick Lenin’s plan for global revolution. The spies in Russian Roulette laid the foundation stones for today's professional secret services and were the inspiration for many fictional heroes, from James Bond to Jason Bourne.

Giles Milton’s book also gives a detailed account of Winston Churchill's chemical weapon campaign against Bolshevik forces in northern Russia in 1919.[4]

Russian Roulette is drawn from previously unknown secret documents held in the Indian Political Intelligence archives and in the National Archives.

Wolfram: The Boy Who Went to War

Wolfram: The Boy Who Went to War is Giles Milton’s seventh work of narrative non-fiction. It recounts the early life of Wolfram Aichele, a young artist whose formative years were spent in the shadow of the Third Reich.

Wolfram Aichele’s parents were deeply hostile to the Nazis. Many of their interests, including freemasonry and the philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, conflicted with the politics of Nazism. Wolfram’s father, the artist Erwin Aichele, managed to avoid joining the Nazi Party. But he could do nothing to prevent his son being drafted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst or Reich Labour Service in 1942, the first inevitable step into the Wehrmacht.

Aichele was sent to the Ukraine and Crimea, where he contracted a life-threatening strain of diphtheria. In 1944 he was sent to Normandy in France, where he served in the 77th Infantry Division as a ‘funker’ or Morse code operator. He took part in the German army’s doomed attempt to halt American troops from breaking out of their beachhead on Utah Beach.

Wolfram Aichele survived a massive aerial bombardment in June 1944. Two months later, he surrendered to American forces and was a prisoner of war, first in England and then in America, where he was interned at Camp Gruber in Oklahoma. When he returned to Germany in 1946, he discovered that his home town, Pforzheim, had been obliterated in the Royal Air Force’s firestorm raid of 23 February 1945.

Giles Milton’s book received widespread critical acclaim for its use of original unpublished source material and its account of the lives of ordinary Germans. In America, the book is published under the title The Boy Who Went to War: The Story of a Reluctant German Soldier in World War II.

Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922

Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922 is Giles Milton’s sixth work of narrative history. It is a graphic account of the bloody sacking of Smyrna (modern Izmir) in September 1922, and subsequent expulsion of 1,300,000 Orthodox Greeks from Turkey and 350,000 Muslims from Greece is recounted through the eyes of the Levantine community. The book won plaudits for its impartial approach to a contentious episode of history.[5]

The story of the destruction of the second city in Ottoman Turkey and subsequent exodus of two million Greeks from Anatolia and elsewhere is told through the eyewitness accounts of those who were there, making use of unpublished diaries and letters written by Smyrna’s Levantine elite: he contends that their voices are among the few impartial ones in a highly contentious episode of history.

The book has won plaudits for its historical balance: it has been published in both Turkish[6] and Greek.[7] The Greek edition has received widespread coverage in the Greek press.It received publicity in the USA when the New York Times revealed that Presidential candidate John McCain was reading it while on the campaign trail in 2008.[8] It featured on a 2008 list of books considered by David Cameron’s Conservative Party to be essential reading by any prospective Member of Parliament.[9]

According to Milton, Smyrna occupied a unique position in the Ottoman Empire. Cosmopolitan, rich and tolerant in matters of religion, it was the only city in Turkey with a majority Christian population. Her unusual demographic had earned her the epithet ‘giaour’ or ‘infidel’. Tensions between Smyrna's Christians and Muslims had first been inflamed by the First Balkan War of 1912–1913. These tensions were to increase dramatically during the First World War. The majority of Smyrna’s population – including the city’s politically astute governor, Rahmi Bey – favoured the Allied cause. They hoped that Turkey, along with her Central Powers partners, would lose the war. The city's political position was to be a subject of intense debate at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919. Greece’s Prime Minister, Eleftherios Venizelos, had long dreamed of incorporating the city into a newly revived Greek Empire in Asia Minor – the so-called Megali Idea or Great Idea, and argued his case with considerable aplomb: American President Woodrow Wilson and Britain’s Prime Minister David Lloyd George eventually consented to Greek troops being landed in Smyrna.

Paradise Lost chronicles the violence that followed the Greek landing through the eyewitness accounts of the Levantine community. The author offers a reappraisal of Smyrna’s first Greek governor, Aristidis Stergiadis, whose impartiality towards both Greeks and Turks won him considerable enmity amongst the local Greek population.

The Greek army was despatched into the interior of Anatolia in an attempt to crush the fledgling army of the Turkish Nationalists, led by Mustafa Kemal. The book provides a graphic account of this doomed military campaign: by the summer of 1922, the Greek army was desperately short of supplies, weaponry and money. Kemal seized the moment and attacked.

The third section of Paradise Lost is a day-by-day account of what happened when the Turkish army entered Smyrna. The narrative is constructed from accounts written principally by Levantines and Americans who witnessed the violence first hand, in which the author seeks to apportion blame and discover who started the conflagration that was to cause the city’s near-total destruction. The book' also investigates the cynical role played by the commanders of the 21 Allied battleships in the bay of Smyrna, who were under orders to rescue only their own nationals, abandoning to their fate the hundreds of thousands of Greeks and Armenian refugees gathered on the quayside.

Many were saved only when a lone American charity worker named Asa Jennings commandeered a fleet of Greek ships and ordered them to sail into the bay of Smyrna. Jennings mission was, contends Milton, one of the greatest humanitarian rescue missions of the 20th century.

Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922 ends with the exodus of two million Greeks from Turkey and the expulsion of 400,000 Turks from Greece – an exchange of population that was enshrined in law in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne.

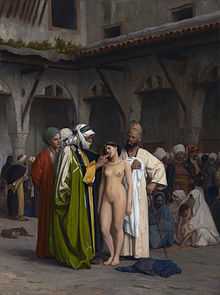

White Gold

White Gold investigates the slave trade in North Africa – the enslavement of white people that saw almost one million Europeans enslaved between 1600 and 1800. and mirrored its black counterpart in the cruelty and degradation of individuals. Milton focuses on the Moroccan slave markets of Salé and Meknes, where slaves were fattened up before being sold at auction. The author reconstructs the voyage of an English ship, the Francis, which was captured by Barbary corsairs in 1716. He investigates the fate of the captured crew, focusing on the cabin boy, Thomas Pellow, who was to be enslaved at the court of the Moroccan sultan for the next twenty three years.

The sultan, Mulay Ismail, a cruel and capricious master: was in the midst of constructing a vast imperial palace to adorn his capital, Meknes. The palace was being built as a conscious attempt by Mulay Ismail to outshine his French contemporary, King Louis XIV, whose Palace of Versailles had been completed a few years earlier. The sultan's slaves – among them Pellow and his 51 shipmates – were compelled to work on the palace's construction. It was gruelling physical labour made worse by the brutal slave drivers who beat any slave who slacked in his work.

Milton's narrative draws on original documents, unpublished diaries and manuscript letters housed in The National Archives and the British Library manuscript collection. White Gold also makes use of the published narrative written by Pellow himself.[10]

One English slave, Abraham Browne, left a detailed account of his life in the days prior to being sold. He was fed 'fresh vitteles [victuals] once a daye and sometimes twice in abondance, with good white breade from the market place.' Browne correctly surmised that the bread was 'to feed us up for the markett [so] that we might be in some good plight agaynst the day wee weare to be sold.'[11] Once bought, most slaves never again saw freedom. The vast majority were to die in captivity.

Thomas Pellow had a different fate: he would eventually escape and make his return to England. He found passage aboard a ship bound for Penryn, Cornwall. When he arrived home in 1738, 23 years after leaving home, Pellow's parents did not recognise their son.

Samurai William

.jpg)

Samurai William is an historical portrayal of the life and adventures of William Adams (sailor) – an Elizabethan adventurer who was shipwrecked in Japan in 1600. William Adams's story inspired the 1975 best-selling novel, Shōgun by James Clavell., recounting the history of early European contacts with the Japanese shogun and the ultimately doomed attempts of the English East India Company to forge profitable trading links with Japan.

William Adams set sail from Rotterdam in 1598, having been employed as pilot on the Dutch ship Liefde (Love). The Liefde was one of five vessels whose ostensible purpose was to head for the Spice Islands or Maluku Islands of the East Indies. But the expedition's financiers also encouraged their captains to attack and ransack Spanish possessions on the coast of South America. The fleet was scattered as it emerged through the Strait of Magellan and into the Pacific Ocean. The captain and crew of the Liefde – concerned that their cargo of broadcloth would not have a ready market in the tropical Spice Islands – took the extraordinary decision to head to Japan, a land of which they were wholly ignorant.

The voyage was fraught with hardship and suffering: atrocious weather and diminishing supplies soon have a deleterious effect on the men's health. On 12 April 1600, William Adams sighted the coast of Japan: by this time, only 24 crew members were still alive.

The book makes use of original source documents – including manuscript letters and journals – to construct a vivid portrayal of Adams's two decades in Japan. The book reveals Adams's personal skill in dealing the Japanese and suggests that he was adept at adapting to Japanese culture. He helped his cause by deliberately creating a divide between himself and the Portuguese Jesuit missionaries who were becoming increasingly unpopular in Japanese courtly circles.

He soon came to the attention of the ruling shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, for whom he built two European style sailing vessels. Ieyasu rewarded Adams with gifts – including a country estate near the imperial capital of Edo. Adams was also honoured with the title of hatamoto or bannerman, a prestigious position that made him a direct retainer of the shogun's court. It also linked Adams to the warrior class that had dominated Japanese history for centuries: all of Adams's fellow hatamoto were samurai. Adams was by now living like the native Japanese. He spoke the language fluently, wore a courtly kimono and changed his name to Miura Anjin (Mr Pilot). He also married a Japanese woman of good birth, even though he had left behind a wife and daughter in England.

Much of Samurai William deals with the ultimately doomed attempts of the East India Company to make use of Adams's influence at court in order to open a trading station at Hirado in south-west Japan. The account of life in Hirado is told through original sources – notably the personal diary of Richard Cocks, head of the factory in Hirado, and the journal of Captain John Saris, commander of the ship that brought the East India Company merchants to Japan. The author quotes widely from original documents now housed in the British Library: these were edited and published by Anthony Farrington in his The English Factory in Japan.

Samurai William provides an account of Adams's death in May 1620, and the sorry decline of the doomed trading post. It ends with the brutal suppression of Christianity in Japan and the closure of the country to foreign trade for more than two centuries.

Big Chief Elizabeth

Big Chief Elizabeth relates the early attempts by Elizabethan adventurers to colonise the North American continent; the book takes its title from the Algonquian Indian word ‘weroanza’, used by the indigenous population in reference to Queen Elizabeth I. It focuses on the pioneering expedition of 1585 to colonise Roanoke Island in what is now North Carolina – an expedition that was financed and backed by the Elizabethan courtier and adventurer, Sir Walter Raleigh.

The historical reconstruction of the attempted settlement makes extensive use of eyewitness accounts written by those who occupied senior positions in Raleigh’s expedition – notably Sir Richard Grenville, Ralph Lane, John White (colonist and artist) and Thomas Harriot, and details the hardships faced by the colonists as they struggled to survive an increasingly hostile environment. It also seeks to explain the enduring mystery of the lost colonists – 115 men, women and children left behind on Roanoke Island when John White returned to England for help.

Giles Milton's 2013 children's book, Children of the Wild, is a fictional recreation of the Roanoke colony. It uses some of the same original sources, notably Thomas Harriot and John White, for background material.

Nathaniel's Nutmeg

Nathaniel's Nutmeg follows the battles between English and Dutch merchant adventurers as they competed for control of the world supply of nutmeg, which commanded fabulous prices in the 17th century, because it was widely (thought erroneously not to have medicinal properties for centuries but recently vindicated [12]) believed to have powerful medical properties.

By 1616, the Dutch had seized all of the principal islands, leaving Run (island) as the only one not in their control. On Christmas Day, 1616, the English adventurer (and East India Company employee) Nathaniel Courthope stepped ashore and persuaded the native islanders to grant him an exclusive monopoly over their annual nutmeg harvest. The agreement that was signed with the local chieftains did far more than that: the document effectively ceded the islands of Run and Ai to England in perpetuity. 'And whereas King James by the grace of God is King of England, Scotland, France and Ireland, is also by the mercy of God King of Pooloway (Ai Island) and Poolarun (Run Island).'[13]

For the next five years, Courthope and his band of starving followers were besieged by a Dutch force one hundred times greater. The Dutch eventually captured Run and killed Courthope. But the English, smarting over their loss of Run, eventually responded by attacking and capturing the Dutch-controlled island of Manhattan.

The ensuing negotiations between the Dutch and English would see the latter relinquish their territorial claim to the island of Run. In return, the Dutch ceded New Amsterdam to England. It was soon renamed New York City.

The Riddle and the Knight

Milton's debut non fiction title, The Riddle and the Knight, is a work of historical detection. It follows the trail of Sir John Mandeville, a medieval knight who claimed to have undertaken a thirty-four year voyage through scores of little known lands, including Persia, Arabia, Ethiopia, India, Sumatra and China. Mandeville subsequently wrote a book about his odyssey: it is widely known as The Travels.

The Riddle and the Knight investigates Sir John Mandeville's purported voyage and the shadowy personal biography of the knight himself. It contends that the widely held assertion[14] – that Mandeville's real identity was John de Bourgogne – is based on a flawed testimony of the chronicler John d'Outremeuse.

The book asserts that Mandeville's autobiographical portrait – in which he claims to be a knight living in St Albans – is probably correct. It also contends that Mandeville was forced to flee his native England when his overlord, Humphrey de Bohun, led a troubled rebellion against King Edward II.

The Riddle and the Knight concludes that the greater part of Mandeville's voyage is fabricated or compiled from earlier sources, notably Odoric of Pordenone, Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and Vincent de Beauvais. In spite of Mandeville's extensive borrowings from other works, Milton offers a reappraisal of Mandeville's place in the history of exploration. Mandeville's Travels captured the imagination of the medieval world and was a source of inspiration to Christopher Columbus as well as notable figures from the Elizabethan era, including Sir Walter Ralegh and Sir Martin Frobisher.

Milton assesses Mandeville's influence on English literature. William Shakespeare, John Milton, and John Keats turned to the Travels for inspiration and until the Victorian era it was Sir John Mandeville, not Geoffrey Chaucer who was known as the 'father of English prose'. Milton's book seeks to restore Mandeville to his literary pedestal, as well as advancing the thesis that he should also be considered the father of exploration.

Critical reception

Russian Roulette

Michael Binyon writing in The Times said: 'Milton has synthesised and filleted a mass of material - old memoirs, official archives and newly released intelligence files - to produce a rollicking tale... which explains the long war against Russia with verve, wit and colour. It reads like fiction, but it is, astonishingly, history.'[15]

Josh Glancy writing in The Sunday Times compared the book to 'the very best of Fleming and Le Carre' and said: 'This gripping history of derring-do and invisible ink brings to life the exploits of the British spies who waged war against Russia during the Cold War.'[16]

Nigel Jones writing in History Today said: 'Milton’s team of spies survived their missions [and] his chronicle of their secret war reads not only like a nail-biting thriller, but a success story… he’s helped by a cast of colourful characters whose real-life exploits are a Bond novel beyond Ian Fleming’s wildest dreams.' [17]

The Daily Express said of Russian Roulette: 'Milton is a compulsive storyteller whose rattling style ensures this is the antithesis of a dry treatise on espionage. And unlike 007, it's all true.' [18]

Wolfram: The Boy Who Went to War

James Delinpole writing in The Daily Mail called the book ‘idiosyncratic and utterly fascinating... what this book captures well is how, little by little, ordinary Germans were bullied and cajoled into acquiescing with Hitler's insane plans.’[19]

For Daily Express reviewer Christopher Silvester, Milton shows how ‘insidiously Nazism encroached on the daily lives of German citizens... as a portrait of how these civilised individuals were able to survive, this is invaluable.’[20]

Hester Vaizy’s review, ‘A Conflict of Loyalty’ published in The Spectator, 21 May 2011, favourably compared the book with standard histories of Nazi Germany: ‘Milton’s account reveals that Germans, too, experienced real suffering in wartime... without forgetting or denying the crimes perpetrated in Nazi death camps, Milton’s close analysis of the experiences of Germans demonstrates that they too could be victims of the war.’[21]

In his BBC History Magazine article, Roger Moorhouse called Wolfram ‘a very valid and interesting book, which offers an illuminating insight into the experience of ‘ordinary’ Germans living in ‘small-town’ Germany.’ [22]

Paradise Lost

Jeremy Seal, writing in The Daily Telegraph, called Paradise Lost: 'A compelling story... Milton's considerable achievement is to deliver with characteristic clarity and colour this complex epic narrative, Milton brings a commendable impartiality to his thoroughly researched book.[23]

William Dalrymple, writing in The Sunday Times, praised the book for both its impartial approach and its use of original source material written by the Levantine families of Smyrna.

'It is the lives of these dynasties, recorded in their diaries and letters, that form the focus for Giles Milton’s brilliant re-creation of the last days of Smyrna ... Milton has written a grimly memorable book about one of the most important events in this process. It is well paced, even-handed and cleverly focused: through the prism of the Anglo-Levantines, he reconstructs both the prewar Edwardian glory of Smyrna and its tragic end. He also clears up, once and for all, who burnt Smyrna, producing irrefutable evidence that the Turkish army brought in thousands of barrels from the Petroleum Company of Smyrna and poured them over the streets and houses of all but the Turkish quarter.[24]

The Spectator and Literary Review also praised the book for its even-handed approach to the controversial sack of Smyrna.

Writing in the Spectator, Philip Mansel called the book 'an indictment of nationalism ... Milton has gone where biographers of Atatürk and historians of Turkey, who often want Turkish official support, have feared to tread. He has reproduced accounts by individual Armenian, Greek and foreign eye-witnesses, as well as British sailors’ and consuls’ accounts. It is a much needed corrective to official history.[25]

Adam Le Bor, writing in the Literary Review, said: ‘Milton brings the past alive in this vivid, detailed and poignant book by drawing on family letters and archives, and first-hand interviews with those elderly survivors who remember Smyrna’s glory days.’[26]

Alev Adil, writing in The Independent, said 'Giles Milton's engrossing account of the events leading up to the destruction of the city in 1922 is based largely on the previously unpublished letters and diaries of these Levantine dynasties. Milton's book celebrates the heroism of individuals who put lives before ideologies.'[27]

White Gold

Writing in The Independent, Benedict Allen picked it as one of his Books of the Year (2004). 'A romping tale of 18th-century sailors enslaved by Barbary seafarers and sold to a Moroccan tyrant. It has all the usual Miltonian ingredients: swift narrative and swashbuckling high-drama laid on a bed of historical grit.’[28]

In his review in The Observer, Dan Neill, felt the strength of the book was its use of contemporary documents. ‘Drawing on letters, journals and manuscripts written by the slaves.... Milton has produced a disturbing account of the barbaric splendor of the imperial Moroccan court, which he brings to life with considerable panache... White Gold is an engrossing story, expertly told.’[29]

In The Daily Mail, Peter Lewis called the book an ‘extraordinary, eye-opening and most readable revelation of a dark place and shameful episode in our history.’[30]

Tim Ecott, writing in The Guardian, said the strength of the book lay in its two magnificent central characters, Thomas Pellow and Mulay Ismail. He concluded: ‘Milton has ingeniously retrieved and polished a hidden nugget from the remarkable treasure house of British history.’[31]

Lucy Hughes-Hallett’s review in The Sunday Times concluded: ‘Milton’s story could scarcely be more action-packed and its setting and subsidiary characters are as fantastic as its events... Milton conjures up a horrifying but enthralling vision of the court of Moulay Ismail.’

In The Sunday Telegraph, Justin Marozzi wrote: ‘White Gold is lively and diligently researched, a chronicle of cruelty on a grand scale... an unfailingly entertaining piece of history.’[32]

Philip Hensher, writing in The Spectator, was sceptical of Milton’s portrayal of Moulay Ismail’s court, which he felt was too consonant with Western ideas of orientalism: ‘It is all a little too much like a fantasy by Ingres,’ he wrote. But he praised White Gold for being ‘extensively researched’ and concluded that it was ‘an exciting and sensational account of a really swashbuckling historical episode.’[33]

Samurai William

Matthew Redhead, writing in The Times, said: ‘Giles Milton is a man who can take an event from history and make it come alive.... He has a genius for lively prose, and an appreciation for historical credibility. With Samurai William, he has crafted an inspiration for those of us who believe that history can be exciting and entertaining.’[34]

In The Sunday Times, Katie Hickman concluded: ‘Giles Milton has once again shown himself to be a master of historical narrative. The story of William Adams is a gripping tale of Jacobean derring-do, a fizzing, real-life Boy’s Own adventure underpinned by genuine scholarship.’[35]

Writing in The New York Review, the scholarly critic Jonathan Spence was impressed by Milton’s use of documentary source material. ‘Giles Milton presents [Adams’s story] with undisguised gusto. His notes and bibliography make it clear that he has absorbed much of the voluminous secondary literature on this period and on Adams himself.’[36]

Anthony Thwaite, writing in The Sunday Telegraph, agreed that the book strength lay in its source material. ‘Giles Milton has been assiduous in searching through all the published sources ... if it brings more readers to the marvelous story of how West discovered East, and East discovered West, that’s good.’[37]

In The New York Times, Susan Chira said that Milton had written ‘a vivid, scrupulously researched biography ... it is a sheer pleasure to read Milton’s vivid portraits of the small corps of foreigners who traded at the sufferance of Japanese feudal lords.’[38]

The Washington Times agreed: ‘He [Milton] recounts in graphic detail – much from primary sources – the astounding hardships and hardihood of those explorers of a dangerous unknown.’[39]

Big Chief Elizabeth

Janet Maslin, writing in The New York Times,[40] commented: ‘In an exceptionally pungent, amusing and accessible historical account, Giles Milton brings readers right into the midst of these colonists and their daunting American adventure... there’s no question that Mr Milton’s research has been prodigious and that it yields an entertaining, richly informative look at the past.’ 23 November 2000.

Many reviews – among them those published by the above-mentioned The New York Times, The Daily Mail,[41] The Times,[42] The Financial Times[43] The New Statesman[44] and The Observer[45] – singled out Milton’s exceptional talent in making use of original source material.

In Britain’s Daily Mail, Peter Lewis wrote: ‘This grippingly told true adventure story is made all the more immediate by using lavish quotations in wild Elizabethan spelling.’

The Spectator also praised the author for bringing history to life. ‘Milton has a terrific eye for the kind of detail that can bring the past vividly to life off the page,’ wrote reviewer, Steve King. ‘He revels in the grim realities of the early colonists’ experience. There’s disease, famine, torture, cannibalism and every kind of deprivation imaginable. Milton’s findness for the faintly off-colour vignette makes for stomach-turning but compelling reading.’[46]

The Sunday Times concluded: ‘Milton has amassed an impressive amount of information from original sources, and it is evidence from Elizabethan journals that makes this such a vivid story.’[47]

There were a few detractors. Writing in The Guardian, Sukhdev Sandhu expressed admiration for Milton’s writing talents. ‘It’s almost impossible to summarise Milton’s book, from which marvelous, vivid stories spill out like swagsack booty.’ But he noted that the book did little to deconstruct the realities in Imperialism. ‘He [Milton] is in love with deeds not discourse, harking back to popular 19th century historians like J A Froude.[48]

And John Adamson, writing in the Sunday Telegraph, also had reservations about the book. In an article entitled, ‘’History: the director’s cut’’, he argued that the book did not place enough demands on the reader. ‘All you have to do is sit back with your tub of popcorn and let the story unfold.’[49]

Nathaniel's Nutmeg

Martin Booth, writing of Giles Milton’s book in The Times, concluded: ‘His research is impeccable and his narrative reads in part like a modern-day Robert Louis Stevenson novel.’[50]

Nicholas Fearn in The Independent on Sunday wrote: ‘This book is a magnificent piece of popular history. It is an English story, but its heroism is universal. This is a book to read, reread, then, aside from the X-rated penultimate chapter, read again to your children.’[51]

In The Spectator, Philip Hensher wrote: ‘To write a book which makes the reader, after finishing it, sit in a trance, lost in his passionate desire to pack a suitcase and go, somehow, to the fabulous place – that, in the end, is something one would give a sack of nutmegs for.’[52]

Time Magazine said of Nathaniel’s Nutmeg: ‘Milton spins a fascinating tale of swashbuckling adventure, courage and cruelty, as nations and entrepreneurs fought for a piece of the nutmeg action.’[53]

The Riddle and the Knight

Bernard Hamilton, writing in the Times Literary Supplement, noted: 'Although he [Milton] makes no claim to be writing an academic study... he has clearly done a good deal of research into published sources and unpublished records.'[54] He adds: 'Were Sir John alive today, I am sure he would have read Milton's book.'

Anthony Sattin, writing in The Sunday Times, said of the book: 'In the style of true medieval quest, each answer poses another question.' He added: 'The one thing that is irrefutably clear by the final page is that Mandeville's argument that the world was round had an enormous influence on the age of exploration.'[55]

Jason Goodwin, reviewing the book in Punch magazine, concluded: 'We travel with him [Milton] in the end because he has done his research in the British Library... Milton has scaled a mountain of research, and the twist he gives Mandeville's story is made with elegance and conviction.'[56]

But Philip Glazebrook, writing in The Spectator, felt that Sir John Mandeville remained a shadowy figure, in spite of Milton's best efforts. 'The trouble is, I never really believed in Sir John, could never visualise him, never feel an intriguing presence at the heart of the book.'[57]

References

- ↑ Book of the Week, Radio 4, 26–30 April 1999, read by Ben Onwukwe.

- ↑ "Surviving History".

- ↑ The author has expressed his intention to deposit this archive in Exeter University Library.

- ↑

- ↑ "Philip Mansel review in The Spectator, 7 May 2008: 'A much needed corrective to official history.'". Spectator.co.uk. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Kayip Cennet, Smyrna 1922 published by Senocak Yayinlari: ISBN 978-605-60-2848-9

- ↑ XAMENOΣ ΠAPAΔEIΣOΣ: ΣMYPNH 1922 published by Minoas Editions: ISBN 978-960-699-821-8

- ↑ Kirkpatrick, David D. (26 October 2008). "John McCain, Flexible Aggression". The New York Times.

- ↑ "In full: The reading list issued to Tory MPs". Telegraph. 3 August 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ The History of the Long Captivity and Adventures of Thomas Pellow in South Barbary, London, 1740. The book was republished in 1890 under the title: The Adventures of Thomas Pellow of Penryn, Mariner, edited by Robert Brown. A more recent edition is Magali Morsy's annotated French edition, La Relation de Thomas Pellow.

- ↑ Quoted in White Gold, p68

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12616960

- ↑ Cited in Giles Milton's Nathaniel's Nutmeg, p273

- ↑ See, for example, the 1883 edition of Encyclopædia Britannica which says: 'On investigating the sources of the book it will presently be obvious that part at least of the personal history of Mandeville is mere invention. Under these circumstances, the truth of any part of that history, and even the genuineness of the compiler's name, become matter for serious doubt.'

- ↑ The Times, 24 August 2013.

- ↑ Josh Glancy , review of Russian Roulette, Sunday Times, 25 August 2013.

- ↑ "History Today", October, 2013.

- ↑ "The Daily Express", September, 2013.

- ↑ The Daily Mail, 20 February 2011.

- ↑ The Daily Express, 4 February 2011.

- ↑ "A Conflict of Loyalty".

- ↑ Historyextra.com, 9 March 2011.

- ↑ "The Bloody Sacking of Smyrna". London: Telegraph. 4 May 2008.

- ↑ "Snuffed Out In A Single Week". The Sunday Times (UK). 15 June 2008.

- ↑ "Through Levantine Eyes".

- ↑ Literary Review June 2008 pp.12–13

- ↑ Adil, Alev (9 June 2008). "Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922". The Independent (London).

- ↑ "Books of the Year – Features, Books". The Independent (UK). 26 December 2004. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Dan Neill (27 June 2004). "Observer review: White Gold by Giles Milton". The Observer (UK). Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ ‘Cornish slaves of the Sultan’, The Daily Mail, 2 July 2004.

- ↑ Tim Ecott (21 August 2004). "Review: White Gold by Giles Milton | Books". The Guardian (UK). Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Marozzi, Justin (15 June 2004). "The Sultan and the Cornishman". London: Telegraph. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ ‘Pirates of Penzance and Reykjavik', The Spectator, 12 June 2004

- ↑ Eastern Promise, The Times, 8 June 2002.

- ↑ 'The Shipwrecked Englishman Honoured by the Shogun’s Court', The Sunday Times, 23 June 2002

- ↑ The Shogun’s Favourite Brit, 10 April 2003.

- ↑ Thwaite, Anthony (23 June 2002). "Jacobeans in Japan". London: Telegraph. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Chira, Susan (27 April 2003). "Shogun's Pet". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ 'How a 16th Century Englishman landed in Japan', Woody West, 19 January 2003

- ↑ Maslin, Janet (23 November 2000). "BOOKS OF THE TIMES – BOOKS OF THE TIMES – Colonists' Travails in Earliest Virginia". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ The Daily Mail: Murder in the name of tobacco, 4 July 2000.

- ↑ Golden Age of Greed, The Times, 4 August 2000.

- ↑ On Virgin Territory, Financial Times, 28 October 2000

- ↑ New Statesman, 18 September 2000.

- ↑ Stephen Pritchard (27 August 2000). "'The Observer', Virginia slims by Stephen Pritchard, 23/08/2000". Guardian (UK). Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ The Spectator, 19 August 2000

- ↑ Pick of the Week, The Sunday Times, 29 April 2001.

- ↑ Sukhdev Sandhu (5 August 2000). "Guardian review: Big Chief Elizabeth by Giles Milton | Books". The Guardian (UK). Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ The Sunday Telegraph 6 July 2000

- ↑ The Times, 28 February 1999

- ↑ Fearn, Nicholas (28 February 1999). "article published 28/02/1999". The Independent (UK). Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ The Spectator, Money Growing on Trees, 27 February 1999

- ↑ Spice World – The Book, by Helen Gibson, 12 April 1999

- ↑ 'Knight of the Round World', Times Literary Supplement, 2 January 1998.

- ↑ 'East of St Albans', The Sunday Times, 8 December 1998

- ↑ 'The Unsung Traveller', Punch, 25–31 January 1997.

- ↑ The Spectator, 7 December 1996.

External links

|