Giles Jacob

Giles Jacob (1686 – 8 May 1744) was a British legal writer whose works included a well-received law dictionary that became the most popular and widespread law dictionary in the newly independent United States.[1][2] Jacob was the leading legal writer of his era, according to the Yale Law Library.[3]

The literary works of Giles Jacob did not fare as well as his legal ones, and he feuded with the poet Alexander Pope both publicly and in literary form. Pope named Jacob as one of the dunces in his 1728 Dunciad, referring to Jacob as "the blunderbuss of the law". Jacob is remembered well for his legal writing, though not so much for his poetry and plays.[2]

Early life

Giles was born in Romsey, Hampshire, and was baptized on 22 November 1686.[4] His father was Henry Jacob, and his mother's name was Susannah. Giles was the only son among eight children. Henry Jacob was a maltster who lived until 1735.[4]

Giles Jacob appears to have trained at the law in some manner, and was a secretary to Sir William Blathwayt. Working for Blathwayt, he engaged in litigation and dispensation, probably in manorial courts.[4]

Writing career

Jacob's first book, The Compleat Court-Keeper, of 1713 has detailed instructions for how to practically administer estate matters. He combined this with a chronological summary of statute law. Both works were financially successful.[4]

Jacob always had an interest in contemporary poetry and the literary life, and in 1714 he wrote a farce called Love in a Wood, or, The Country Squire. This play was never produced. He persisted, however, and in 1717 he wrote a satire of Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock in the form of The Rape of the Smock. The poem was low and bawdy, and the next year he wrote Tractatus de hermaphroditus.[4]

In 1719, two works appeared by Jacob, both great successes. The first was Lex constitutionis, which was a thoroughly researched compendium of statute law, common law, and criminal law, schematized according to which powers of the executive branch of the government were involved. While the work's fame and usefulness were surpassed in a few years, Jacob's book was a well regarded analysis. The same year, he produced the first volume of the Poetical Register, with a second volume in 1720. This work provided biographies of contemporary authors as well as earlier ones. According to the literary editor Stephen Jones:[5]

[H]e is generally accurate and faithful, and affords much information to those who have occasion to consult him. It cannot be denied that he possessed very small abilities; but he was fully equal to a task where plodding industry, and not genius, must be deemed the essential qualification.

In the Poetical Register, Jacob criticized the play Three Hours After Marriage (1717), which had been written by John Gay, John Arbuthnot and Alexander Pope, saying that its scenes "trespass[ed] on Female Modesty".[4] Jacob subsequently criticized that play for "obscenity and false Pretence".[4] Jacob had admired Pope, had been on good terms with him, and had submitted the biographical entry of Pope (in the Poetical Register) to Pope himself for correction, and Jacob was surprised when Pope attacked him for Jacob's criticism of Three Hours After Marriage. Jacob perhaps did not know that Three Hours After Marriage had been co-authored by Pope. In The Dunciad of 1728, Pope pounced:[4]

Jacob, the scourge of grammar, mark with awe,Nor less revere the blunderbuss of law.

Pope explained Jacob's offense as follows: "he very grossly and unprovoked abused in that book [the Poetical Register] the author’s friend, Mr. Gay".[6] Thomas Lounsbury, a literary historian and critic, has explained that no one criticized Three Hours After Marriage "without incurring an enmity that never died out".[6]

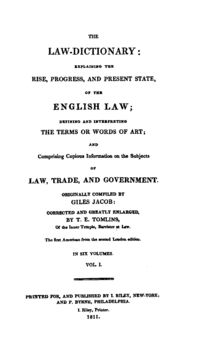

In 1725, Jacob wrote The Student's Companion and regarded it has his favorite of the books he had written. It was a guide to studying law, with practical tips, reviews, and indexes. In 1729, his most famous work, nine years in the making, appeared: A New Law Dictionary. It combined a dictionary of legal practice with an abridgment of statute law, and it reached its fifth edition by the time of Jacob's death. As late as 1807, "Jacob's Law Dictionary" was still a very profitable copyright.[4] His last work was Every Man his Own Lawyer, which outsold even the law dictionary. It was a self-help book for average citizens who might be involved in litigation.

Personal life

Jacob married Jane Dexter in 1733, and they had at least one daughter, Jane.[4] He and his family moved to Staines, Middlesex, where he died on 8 May 1744.[4]

References

- ↑ Levy, Leonard. "Origins of the Fifth Amendment and its Critics", Cardozo Law Review, Vol. 19, p. 854 (1997).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 McDowell, Gary. The Language of Law and the Foundations of American Constitutionalism, p. 172 (2010).

- ↑ Greenwood, Ryan. "The Taussig Collection: Giles Jacob" (January 8, 2014).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 Kilburn, Matthew. "Giles Jacob" in Matthew, H.C.G. and Brian Harrison, eds. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. vol. 29, 546–7. London: Oxford UP, 2004.

- ↑ Baker, David and Jones, Stephen. Biographia Dramatica: pt.1. Authors and Actors: A-H, p. lxxii (Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, 1812).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lounsbury, Thomas.The Text of Shakespeare: Its History from the Publication of the Quartos and Folios Down to and Including the Publication of the Editions of Pope and Theobald, Volume 3, p. 324 (C. Scribner's sons, 1908).

External links

|