Geuzen medals

Geuzen medals or Beggar’s medals (also Sea Beggars medals) were coined during the early days of the Dutch Revolt and the first half of the Eighty Years' War in the 16th century. During that period, a lot of medals, tokens and jetons with a political message were issued. This article deals with the earliest Geuzen medals or tokens, i.e. from the mid-century to 1577.

In the Dutch language a "geus" - plural "geuzen" - is a familiar word for people who revolted in the 16th century against the Spanish king Philip II. It started with the nobility, then the gentry and finally the common folk (all on land). Some years later, when war broke out, the title "geus" or specifically "watergeus" (meaning marine “geus”) was given to the rather irregular force of rebels fighting and living in the estuaries of the big rivers and as a distinction sometimes the name "bosgeus" ("geus" of the forest) was given to the originals.

"Geus" is derived from the French word for beggar, hence the translation of "watergeus" into "sea beggar". The expression "sea beggar" by extension now is also being applied for a land bound "geus".

Background

The Holy Roman Empire was still at war with France when, in 1555, Philip II of Spain succeeded his father, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. After peace was made, Philip II appointed his half-sister Margaret of Parma as viceroy in the Low Countries and departed for Spain. The real power was invested in the three permanent members of the "Raad van State", the High Council, Cardinal Granvelle, Viglius and Berlaymont (later the three were called the Consultá; they were permanent members in the sense that for their office they stayed at court, while the non-permanent members mostly executed functions abroad). The high nobility like William of Orange (or William the Silent, “stadhouder”, which means Lord lieutenant, of Holland, Zealand and Utrecht) and Lamoral, Count of Egmont, (“stadhouder” of Flandres) were members of the “Raad van State”, the High Council, but became discontented by their loss of power, specifically to Granvelle and also because Spanish troops still remained in the Low Countries after the peace with France. Using a French example, they instituted the “Ligue”, a coalition of the high nobility. The activity of the “Ligue” resulted in the departure of Spanish troops in 1564 and shortly thereafter the retirement of Granvelle.

Seeing this success, members of the low nobility, who had been impoverished in the previous decades (like the common people in the southern parts of the Low Countries) united themselves in 1565 in the “Compromis”. Their political program sought relief from the harsh measures against the Reformation. In early April 1566 400 members of the “Compromis“ united in Brussels. On April 5, led by Henry, Count of Brederode, and Ludwig of Nassau, they presented a petition to Margaret, who was alarmed at the appearance of so many men. Berlaymont is supposed to have whispered to her, “Ce ne sont que de gueux”, (“They're just beggars”).

Three days later, April 8, during a banquet in the palace of the earl of Culemborg, hearing Brederode, the scorning word “geus” was chosen as a sign of honour for their group, constituting sort of a mocking order of knights. They decided to adopt a costume that incorporated mendicant symbols such as beggars' bowls and flagons. This was less an eccentricity of the low nobility and more a sort of popular tradition in reversing roles, as at carnival time. A dress code with symbols such as beggars' bowls and flagons at the one side and - as will be told later - a silver or gilt token on a ribbon around the neck showed them as independent and dominant. There may also have been an element of mockery of the church, as mendicant monks also used such implements.

In using words like noble and nobility one should not suppose that those folks in general all behaved according to our understanding of this term. Sometimes the lower Flemish nobility of the 16th century might be better characterized by “successful criminals”. When Charles V went for the first time went to Spain in 1517 and did not land on the preselected spot because of stormy weather, the disappointed Flemish nobles of his court behaved so badly - marauding, murdering innocent people, (all according to Alonso de Santa Cruz) - that officials went to great lengths to ensure that king Charles should not be told. In 1572 William de la Marck, Lord of Lumey, also lower Flemish nobility, took Den Briel for William the Silent. Nineteen Gorinchem captured Roman Catholic clergy were brought to him in Den Briel. After torturing and other cruelties they were hanged on his orders, where William of Orange specifically had requested to be lenient toward Roman Catholic clergy.

In the 16th century, beggars frequently were not allowed to beg without getting permission from local municipality or lordship. Already, sometimes permission was only granted if they would visibly wear a small tin or copper token, that way recognizable as sort of an official beggar. This could well be the origin for Geuzen medals as will be seen hereafter.

Probably the first political Geuzen medal

Letters between Granvelle, at that time in Madrid, and his secretary Morillon in Brussels show that Jacques Jonghelinck, master medal maker with a workshop in one of the buildings of the palace complex in Brussels, in the spring of 1566 had made a mould for a small medal. Successively he cast medals in lead, tin, copper, silver or gold (specimens in tin or copper now are unknown; a very few specimens in lead are found, but because lead is inherently soft - so the medal is not "stable", its eyelet is of questionable authenticity - lacking proof that they are real originals and not later date copies). On June 15 Morillon sent a lead specimen to Granvelle with the sneer that more medals were cast in lead then in the other metals; a medal for poor people “affin peult-estre gue les Geutz demeurent en leur qualité”, something like “perhaps the quality (of the medals) being in line with the standing of the Geuzen”. Most probably such a medal, cast silver and original gilt, is shown in the next picture.

There is no absolute proof that this is the earliest type of Geuzen medal and was produced by Jacques Jonghelinck, the point being that on original paintings and prints it is through lack of details not very well possible to distinguish between this medal and the two to be discussed next. The medal is described in part I of the book by Gerard van Loon “Beschrijving der Nederlandse Historipenningen ….”, 1713–1731, and now has the collectors reference vL.I 85/84.5. It is qualified as “rare to very rare”. The medal is small, just an inch not counting the eyelet. It shows the bust of Philip II, with “1566” on its cut and the text “EN TOVT FIDELLES AV ROY” and on the reverse side a beggar's bag or sack, hands and the text, “IVSQVES A PORTER LA BESACE”.

The texts mean something like “In everything loyal to the king” and “even condemned to beggars’ level”. The medal was worn on the breast with a ribbon around the neck . Morillon gives the information that Jonghelinck’s neighbouring “tourneur”, doubtless a master furniture maker, turned many small wooden bowls that ladies wore hanging from their ears (now original specimens are unknown). Authentic pictures sometimes show the nobility wearing model beggar’s bowls and flasks, fastened to the same ribbon. On the reverse side of the medal shown above, some wear is visible due to contact with breast armour.

Of this type of medals about half of the known specimens have their eyelet broken off. That is due to fashion in the late 17th and 18th century, when a medal with an eyelet did not show off beautifully in a collector’s cabinet (even nowadays museums sometimes buy early medals with an eyelet broken off, unaware of yesterday’s fashion and of complete specimens in other collections). Early in the 17th century, when it became clear that the Dutch were going to win their Eighty Years' War, there was a growing demand for Geuzen medals, because now it was safe to be a geus. From that moment Jonghelinck’s medal was copied, mostly not cast but in struck silver, mostly slightly bigger to show off better and already sometimes with attached beggar’s bowls and flasks.

An early political Geuzen medal by an unknown medal maker

Morillon writes on July 7, 1566, to Granvelle that he got angry at Jonghelinck “because he had broken his first Geuzen medal“ (it is likely that Morillon means that Jonghelinck had broken his mould), but he expected that Jonghelinck could reproduce (his mould), even though he made only a very small profit on his first version. It is (yet) unknown who is the medal maker of the cast silver, gilt, Geuzen medal with collectors reference vL.I 85/84.4 and the qualification “very rare” shown next.

The text is nearly identical to the Jonghelinck medal with the exception that “1566” is now put in the text, but note that there are now hollow points inserted between the words. The medal is slightly bigger and “fuller” then the former one. On the reverse there is no beggars bag or sack but two nobles shaking hands. The left noble has a beggars bowl and flask on his hip. Between the feet of the nobles is a monogram, most likely "VLG”, probably meaning "Vive le Geux", but it could also refer to the medal maker. Maybe this medal is also shaped by Jonghelinck or a befriended or cooperating medal maker; there is reasonable similarity in style and production method and the monogram does not bar the assumption. Dating the medal is more difficult, because “1566” in the text is not decisive (on the former medal “1566“ was found on the cut of the neck of Philip II, so being much more decisive). One of the nobles already retains beggars’ bowl and flask, but the other noble does not yet wear a Geuzen medal on a ribbon, which we will find on a Geuzen medal of 1572, to be discussed later. On the other hand people in 1566 began to revolt extremely, the so-called “beeldenstorm” or Protestant iconoclasm, starting August 16 in Steenvoorde. The king, Margareta, the Consultá and the high nobility are furious, recollecting what happened 30 years earlier in Münster, Genève and Augsburg and 10 years earlier in Scotland, for that reason definitely no concessions. The majority of the lower nobility is also shocked and the “Compromis” is disbanded, most nobles swear their loyalty to the king again. A medal with a mixed character, King and reverse Geus, is then unthinkable. For those reasons the best guess is that this medal dates from early summer 1566, to be more specific after July 7 and before the end of August.

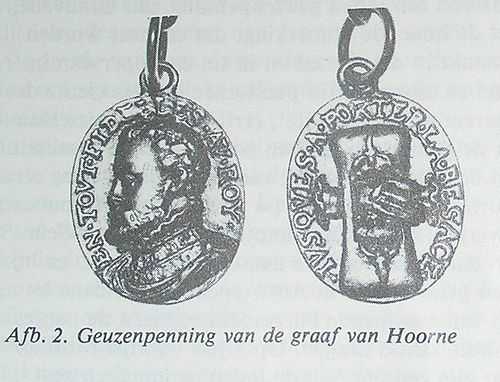

Van der Meer (see references) presents another geuzen medal, this time in gold, where it is said that this one belonged to Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn. This medal is nearly identical to Jonghelinck's medal, but it has points (not hollow ones) inserted between the words of the text. The authenticity of that medal is not to be discussed, a question mark could only arise around it to be worn by the Count of Hoorne, who was executed on command of the duke of Alba in 1568. Maybe this third medal is also cast by Jonghelinck or a befriended or cooperating medal maker. To give a fair impression of this last medal a picture of an illustration in Van der Meer's article is given.

The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam possesses a piece of tapisserie. It shows the famous maiden Kenau Simonsdochter Hasselaer of Haarlem during the siege of that city in 1572-73 (if you visit the website of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, go to "collection" and search for "geuzenpenning", the tapisserie will be one of three "hits"). We see Kenau, assisted by two other armed maidens, wearing a geuzen medal on a ribbon around her neck. Even the effigie of the Spanish king is being suggested.

A Geuzen medal for the Protestants from medal maker “little lobster”

The following medal, silver cast and tooled, is also called “half moon of Boisot” because the Geuzen, this time Watergeuzen or Sea Beggars, commanded by Boisot, wore this medal fixed to their hats at the relief of Leiden in 1574.

The medal measures about 35 mm. The text reads “LIVER TVRCX DAN PAVS” (“Rather Turkish than Papist“) and “EN DESPIT DE LA MES” (“In spite of the Mass”). Note the “little lobster” emblem between “…PIT” and “DEL…”, the privy mark or “huismerk” of the medal maker. In the 16th century most metal (including gold and silver) items and also good pottery was produced with a privy mark, resulting in later periods in assay marks for silver and gold objects. We do not know the man (for that period we can exclude females) whose emblem was the “little lobster”. Anyhow, we should not trust “half moons” made out of rolled silver plate by sawing and engraving if they show an engraved “little lobster”. Such work is later, where the maker did not recognise this mark as a privy mark. A faithful silversmith would put his own mark in the proper spot or probably nothing in case of an early specimen.

The medal has the reference vL.I 192/190 and the qualification “rare to very rare”. In the Stedelijk Museum De Lakenhal in Leiden this medal is shown in a display on city history, but there is a little silver ring attached to the eyelet, probably meaning that this medal was worn on a silver chain in later days.

These medals were also worn by the Sea Beggars at the capture of Den Briel in 1572.

The medal itself and its background doubtless is older than 1572. Wearing half moons was already in practice in and around Antwerp by attendants of “hagepreken”, open-air sermons, by Herman Modet. Modet created the slogan “Liever Turks dan paaps” (“Rather Turkish than Papist”), or anyhow was the one who spread it. Some time later he became parson with the Watergeuzen or Sea Beggars and there reintroduced wearing half moons, where in other places it had become out of fashion.

The Rijksmuseum of Amsterdam possesses also a "half moon". They date the specimen 1574 (if you visit the website of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, go to "collection" and search for "geuzenpenning", the "half moon" will be one of three "hits"). It is also in cast silver but it is roughly tooled. There is also a slight difference in the lettering. It shows that already at that time there was a shortage of this type of Geuzen medals.

A token on the “tiende penning”, the 10 percent sales tax, 1572

The Duke of Alba, in his effort to strengthen the power of king Phillips II in the Low Countries, wanted to get rid of the “bede” - the regular plea for money - to the “Staten”. This could only be done by introducing taxation. So in 1569 he wanted to introduce a one time tax of 1% on property and a few years later a regular tax of 5% on property sales (this type of tax with the same level is still in use in the Netherlands). At the same time Alba wanted a regular sales tax of 10%, i.e. one in ten, as a sort of VAT. The last one was called the “tiende penning” and was met with furious opposition, so Alba accepted a deferral of two years for a hefty sum of money. William of Orange, one of the opponents, was seen as a hero and an unknown medal maker cast a silver token as illustrated. This token is discussed because it bears relation to the next Geuzen medal.

The not very impressive small token, diameter 28 mm, shows William of Orange in harness with sword and battle hammer. The text reads “P.V.O” or “Prince of Orange” and “DAT EDEL BLOET”, literally “that noble blood”. On the reverse 9 “penningen” are shown on a coat of arms, text “HEFT ONS VOER DEN 10 PENNINCK BEHOT” or “has guarded us against the 10th penning”. This silver, cast, token has collectors reference vL.I 157/155.1 and the qualification “very rare“. More frequently this token is found with a greater diameter and not cast but struck. This is because already in the 17th century this token was rare; by growing demand from collectors the token was “reissued”, struck because casting was already more or less obsolete. And as a tribute to the founder of the republic and the deferral of the “tiende penning” it had to look more impressive. Sometimes collectors are prepared to pay a better price for the “reissued” token then for the original.

A political Geuzen medal, 1572, as token

1572 is an extraordinary year in Dutch history, the taxation on the “tiende penning” is prohibited, and the Sea Beggars take the city of Den Briel for the Prince of Orange. Vlissingen, Veere and Enkhuizen take the side of the Prince. Reason to celebrate these facts and issue forth a medal. One could not foresee the chances in the war turning very bad later that year (Mechelen castigated, Naarden massacred and Haarlem besieged). The medal is struck on a cast silver plate, originally without an eyelet, collectors reference vL.I 148/145 and qualification “extremely rare” (a comparable medal, silver, gilt, with an eyelet and a small ring, equal collectors reference and qualification was on auction at Laurens Schulman b.v. in April 2002).

On the medal, 38,5 mm high, is presented a sword with a “penning” on top between two ears, left a spectacle and flute, right 9 “penningen”. The text reads “EN TOVT FIDELLES AV ROY 1572”. The medal partly struck weakly, the date is difficult to read. Reverse shows two nobles, one with beggars bowl and flask and the other with an oversized Geuzen medal. The text reads “IVSQVES A PORTER LA BESASE”. Because of the two texts this medal belongs to the category of Geuzen medals (it was also “reissued” in the 17th century, but struck on rolled silver plate). The symbolism “ears” refers to Alba, who should listen and spectacles is associated with the seize of Den Briel, the last may sound in Dutch as “bril”, i.e. “spectacles”. Although fighting was already fierce, it still lasted 9 years before Philip II in 1581 was no longer acknowledged as sovereign by the “PLACCAERT VAN VERLATINGHE”. The 9 plus one “penningen” relate to the prohibited taxation of the “tiende penning”.

The purpose of both medals or tokens, dated 1572, is not clear; were they issued just to commemorate or was their aim also or more to be a token you presented to important friends to show that you belonged to the elite that supported the Geuzen or William of Orange. In view of the difficult economic situation, where there was little room for luxury, the use as token is most likely.

The "eternal edict" of 1577

After the “Pacification of Gent" Don Juan, or John of Austria, comes to an agreement with the "Staten-Generaal" and accepts the "Pacification". Jacques Jonghelinck, most likely the master medal maker of the first Geuzen medal - where he did not make much profit, according to Morillon - at that moment master of the mint of Antwerp (1572 to 1606), sees profit in the enthusiasm of the elite and produces a silver memorial medal to be cast in great numbers. The reference code is vL.I 243/230 and there is no qualification of rarity.

Almost all medals are found as shown with a border of "vuurslagen" (flint strikers) and an eyelet, or a spot where the eyelet is broken off. The purpose was to show the medal as adornment. Jonghelinck tried to maximise his profit by minimising on silver in the casting process, many medals showing small holes due to very thin casting. The production in great numbers and the size of the medal demonstrate that now the economy had started to boost.

Geuzen medals with attachments as beggars’ bowls and flasks

About 1600 it becomes clear that the northern part of the Low Countries is going to win the war against Spain. As expected the number of Geuzen multiplies. Since also prosperity has increased Geuzen medals are very much in demand. The very few issues of 1566 to 1572 are manifold copied by striking or engraving on rolled silver plate and not by casting. Also new types are developed and struck. Early in the 17th century it becomes fashion to attach small beggars’ bowls and flasks to the medal. About 1700 Jonghelincks’ Geuzen medal becomes the most frequently struck, but now with one beggars’ bowl and two flasks attached. That is also the kind of execution of today’s Geuzen medal as award for exceptional merits.

If you visit the website of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, go to "collection" and search for "geuzenpenning", another early copy of Jonghelincks' Geuzen medal in silver with beggars' bowl and flasks is shown.

References

- For historical facts a publication by G. van der Meer in "de beeldenaer" of May/June 1980, 4th year nr 3, has been gratefully used and idem a publication by K. F. Kerrebijn in ibidem of July/August 2001, 25th year nr 4, both in Dutch.

- The picture of the Geuzen medal, silver 19th and 20th century, kindly is provided by Laurens Schulman b.v.