Germany–United States relations

|

|

Germany |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic Mission | |

| German Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Berlin |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Peter Wittig | Ambassador John B. Emerson |

German–American relations are the relations between Germany and the United States. Today, the United States is regarded as one of the Federal Republic of Germany's closest allies and partners outside of the European Union.[1] In 2014 relations have strained slightly as a result of revelations that the U.S. National Security Agency wiretapped the phone of Chancellor Angela Merkel and the arrests of two German intelligence officials suspected of spying for the C.I.A..[2]

Country comparison

| |

| |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 82,060,000 | 320,892,000 |

| Area | 357,021 km² (137,847 sq mi) | 9,526,468 km² (3,794,066 sq mi)[3] |

| Population density | 246/km² (637/sq mi) | 31/km² (80/sq mi) |

| Capital | Berlin | Washington, D.C. |

| Largest city | Berlin – 3,431,700 (5,000,000 Metro) | New York City – 8,175,133 (19,006,798 Metro) |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic | Federal presidential constitutional republic |

| First Leader | Konrad Adenauer | George Washington |

| Current Leader | Angela Merkel | Barack Obama |

| Official languages | German (de facto and de jure) | English (de facto) |

| Main religions | 64% Christianity, 29.6% Irreligion, 5% Islam, 0.25% Judaism, 0.25% Buddhism, 0.10% Hinduism, 0.09% Sikhism | 75% Christianity, 20% non-religious, 2.5% Judaism, 1% Buddhism, 0.6% Islam, 0.4% Hinduism, 0.5% other Religions |

| Ethnic groups | 80% German, 4.3% Turkish, 17.7% other | 74% White American, 13.4% African American, 6.5% Some other race, 4.4% Asian American, 2.0% Two or more races, 0.68% Native American or Native Alaskan, 0.14% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander |

| GDP (nominal) | $3.66 trillion ($44,660 per capita) | $14.441 trillion ($47,440 per capita) |

| German Americans | 99,891 American born people living in Germany[4] | 50,764,352 people of German ancestry living in the USA |

| Military expenditures | $45.93 billion (FY 2008)[5] | $663.7 billion (FY 2010)[6] |

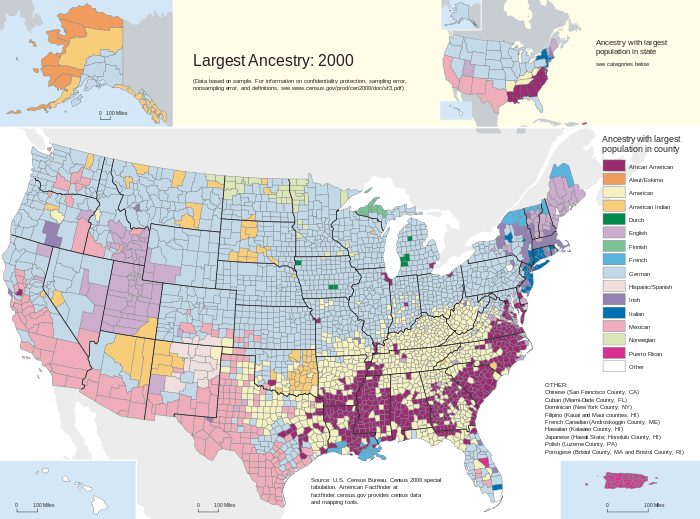

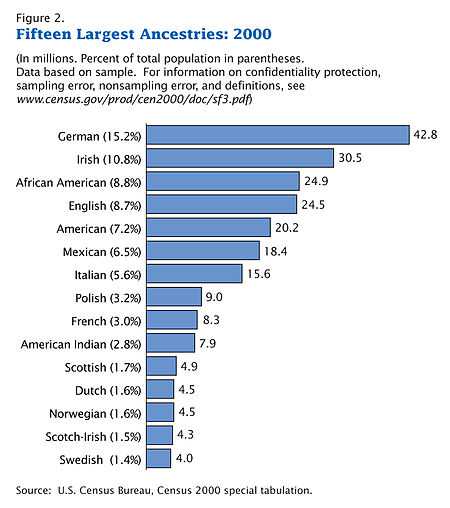

German immigration to the United States

For over three centuries, immigration from Germany accounted for a large share of all American immigrants. As of the 2000 U.S. Census, more than 20% of all Americans, and 25% of white Americans, claim German descent. German-Americans are an assimilated group which influences political life in the US as a whole. They are the most common self-reported ethnic group in the northern half of the United States, especially in the Midwest. In most of the South, German Americans are less common, with the exception of Florida and Texas.

1683–1848

The first records of German immigration date back to the 17th century and the foundation of Germantown near Philadelphia in 1683. Immigration from Germany to the US reached its first peak between 1749 and 1754 when approximately 37,000 Germans came to North America.

1848–1914

Since 1848, about seven million Germans have emigrated to the United States. Many of these Germans settled in the cities of Chicago, Detroit and New York. The failed German Revolutions of 1848 accelerated emigration from Germany. Those Germans who left as a result of the revolution were called the Forty-Eighters. Between the revolution and the start of World War I over one million Germans settled in the United States.

These Germans endured hardship as a result of overcrowded ships; Typhus fever spread rapidly throughout the ships due to the cramped conditions. On average, it took Germans six months to get to United States and many died on the journey to the New World.

By 1890 more than 40 percent of the population of the cities of Cleveland, Milwaukee, Hoboken and Cincinnati were of German origin. By the end of the nineteenth century, Germans formed the biggest self-described ethnic group in the United States and their customs became a strong element in American society and culture.

Political participation of German-Americans was focused on involvement in the labor movement. Germans in America had a strong influence on the labor movement in the United States. Newly founded labor unions enabled German immigrants to improve their working conditions and to integrate into American society.

Since 1914

A combination of patriotism and anti-German sentiment during the two world wars caused most German-Americans to cut their former ties and assimilate into mainstream American culture. During the time of the Third Reich, Germany had another major emigration wave of German Jews and other political refugees.

Today, German-Americans form the largest self-reported ancestry group in the United States[7] with California and Pennsylvania having the highest number of German Americans.

Perceptions and values in the two countries

Germany and the United States are civil societies. Germany's philosophical heritage and American spirit for "freedom" interlock to a central aspect of Western culture and Western civilization. Even though developed under different geographical settings, the Age of Enlightenment is fundamental to the self-esteem and understanding of both nations.

It can also be observed that both countries have experienced the ideology of white supremacy. When the Congress of the Nazi Party met in 1935 to pass their Nuremberg Laws, they were in many ways modeled on the Jim Crow laws which were in place in the USA from 1877 to 1954.[8]

Both countries value work ethic and respect a sense of right and order. The image of an Ugly American corresponds to the "Ugly German".[9] A high level of cultural exchange has led to relatively strong views of each other, both positive and negative. Americans tend to view Germans as efficient and orderly, yet routinely mock them for their Nazi past. German views of Americans on the other hand often resemble those of Canadians toward Americans. Nevertheless, both Americans and Germans visit each other's countries routinely, for business or study.

The U.S.-led invasion of Iraq has also changed the perception of the U.S. in Germany significantly. A 2013 BBC World Service poll shows found that 35% find American influence to be positive while 39% view it to be negative.[10] Both countries differ in many key areas, such as energy and military intervention.

A survey conducted on behalf of the German embassy in 2007 showed that Americans continued to regard Germany's failure to support the war in Iraq as the main irritant in relations between the two nations. The issue was of declining importance, however, and Americans still considered Germany to be their fourth most important international partner behind the United Kingdom, Canada and Japan. Americans considered economic cooperation to be the most positive aspect of U.S.-German relations with a much smaller role played by Germany in U.S. politics.[11]

Among the nations of Western Europe, German public perception of the U.S. is unusual in that it has continually fluctuated back and forth from fairly positive in 2002 (60%), to considerably negative in 2007 (30%), back to mildly positive in 2012 (52%),[12] reflecting the sharply polarized and mixed feelings of the German people for the United States.

Political relations

Pre-1871

The United States did not immediately establish formal diplomatic relations with any of the German states. Several economic agreements were made; however, including a 1785 trade agreement with the Kingdom of Prussia. The first representative of the United States in a German state came with the appointment of John Quincy Adams as Minister to Prussia in 1797. This was short-lived; however, and the United States had no permanent representation in Germany until 1835 when Henry Wheaton was appointed by Andrew Jackson. Meanwhile, the first German representation in the United States was established in 1817, when King Frederick William III's appointed Friedrich von Greuhm as Minister to the United States. This legation would be transformed to the North German Confederation in 1868.

German Empire and two world wars

Caribbean

In the late 19th century the German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) sought to establish a coaling station somewhere in the Caribbean. Germany was rapidly building a world-class navy but coal burning warships needed frequent refueling and could only operate within range of a coaling station. Preliminary plans were vetoed by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who did not want to antagonize the U.S. He was ousted in 1890 and the Germans kept looking.[13]

German naval planners in the 1890-1910 era denounced the Monroe Doctrine as a self-aggrandizing legal pretension. They were even more concerned with the possible American canal, because it would lead to full American hegemony in the Caribbean. The stakes were laid out in the German war aims proposed by the Navy in 1903: a "firm position in the West Indies," a "free hand in South America," and an official "revocation of the Monroe Doctrine" would provide a solid foundation for "our trade to the West Indies, Central and South America."[14] By 1900 American "naval planners were obsessed with German designs in the hemisphere and countered with energetic efforts to secure naval sites in the Caribbean."[15]

In the Venezuela Crisis of 1902–1903 Britain and Germany sent a warships to blockade Venezuela after it defaulted on its foreign loan repayments. Germany intended to land troops and occupy Venezuelan ports, but U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt forced the Germans to back down by sending his own fleet and threatening war if the Germans landed.[16]

By 1904 German naval strategists had turned its attention to Mexico where they hoped to establish a naval base in a Mexican port on the Caribbean. They dropped that plan, but became active again after 1911 when Mexico fell into Civil War.[17]

World War I

During World War I, the United States initially sought isolation, but eventually joined the Allied powers. The German Navy waged unrestricted warfare across the Atlantic Ocean often resulting in American casualties. Berlin refused to stop the unrestricted naval bombardments. Ultimately, the Zimmermann Telegram, a top secret message sent from the German Empire to Mexico was the catalyst which brought America into the war. The details of the plan infuriated Americans; Germany suggested an invasion of the U.S. by Mexico if America entered the war. This would keep the U.S. from deploying troops to Europe and Germany would still be able to wage unrestricted naval warfare to cut British supplies. In return, when the war was won by the Central Powers, Mexico would be rewarded with the territory lost during the Mexican–American War.

President Woodrow Wilson convinced Congress to declare war on the German Empire and the Central Powers. The United States entered World War I in 1917, providing a crucial injection of troops and resources to the Allies. After the exit of Russia from the war that same year, Germany could reallocate approximately 600,000 experienced troops to their Western Front; but with the entry of the United States into the war, the Allies outnumbered the Germans. The Allies succeeded in defeating the German Empire and their Central Power allies.

Back home in the United States, German-Americans were frequently discriminated against. Any significant German cultural impact on the U.S. was seen with intense hostility and suspicion. The German Empire was portrayed as a threat to American freedom and way of life. In Germany, the United States was another enemy and considered a false liberator, wanting to dominate Europe itself.

World War II

The Second World War made German-American relations worse. The attack on Pearl Harbor by Imperial Japanese forces brought the U.S. into the conflict, where it once again fought Germany. The United States played a central role in the defeat of the Axis Powers, meaning relations between Berlin and Washington, D.C. were inevitably terrible. Nazi Germany used American participation as one of the leaders of the Allies for extensive propaganda value—the infamous "LIBERATORS" poster from 1944 may be the most powerful example.

In the poster, which is shown in this article, the United States of America is depicted as a monstrous, vicious war machine seeking to destroy European culture. The poster alludes to many negative aspects of American history, including the Ku Klux Klan, the oppression of Native Americans, and lynching of blacks. The poster condemns American capitalism, America's perceived dominance by Judaism and shows American bombs destroying a helpless European village. However, America launched several propaganda campaigns in return towards Nazi Germany often portraying Nazi Germany as a warmongering country with inferior morale, and brainwashing schemes.

Post war

Following the defeat of the Third Reich, American forces were one of the occupation powers in postwar Germany. In parallel to denazification and "industrial disarmament" American citizens fraternized with Germans which was – despite an initial partly based on ancestor relations, among other reasons. The Berlin Airlift from 1948–1949 and the Marshall Plan (1948–1952) further improved the Germans' perception of Americans.

Cold War

The emergence of the Cold War made the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) the frontier of a democratic Western Europe and American military presence became an integral part in West German society. The American presence may have helped smooth over possibly awkward postwar relationships, had they not come under the aegis of the biggest intact army and economy. This lessened the lag before the formation of the precursors to today's EU, and may be seen as a silent benefit of Pax Americana During the Cold War, West Germany developed into the largest economy in Europe and West German-U.S. relations developed into a new transatlantic partnership. Germany and the U.S. shared a large portion of their culture, established intensive global trade environment and continued to co-operate on new high technologies. However, German-American cooperation wasn't always free of tensions between differing approaches on both sides of the Atlantic. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent reunification of Germany marked a new era in German-American relations.

U.S. and East Germany

Relations between the United States and East Germany remained hostile. United States followed the Adenauer's Hallstein Doctrine of 1955, which declared that recognition by any country of East Germany would be treated as an unfriendly act by West Germany. Relations between the two Germanies thawed somewhat in the 1970s, as part of the overall détente between East and West. United States recognized East Germany officially in September 1974, when Erich Honecker was East Germany's party leader. To ward off the risk of internal liberalization on his regime, Honecker enlarged the Stasi from 43,000 to 60,000 agents.[18]

The East German regime imposed an official ideology that was reflected in all its media and all the schools. The official line stated that the United States had caused the breakup of the coalition against Adolf Hitler and had become the bulwark of reaction worldwide, with a heavy reliance on warmongering for the benefit of the "terrorist international of murderers on Wall Street." East Germans had a heroic role to play as a front-line against the evil Americans. However few Germans believed it. They had seen enough of the Russians since 1945—a half-million Soviets were still stationed in East Germany as late as 1989. Furthermore they were exposed to information from relatives in the West, as well as the American Radio Free Europe broadcasts, and West German media. The official Communist media ridiculed the modernism and cosmopolitanism of American culture, and denigrated the features of the American way of life, especially jazz music and rock 'n roll. The East German regime relied heavily on its tight control of youth organizations to rally them, with scant success, against American popular culture. The older generations were more concerned with the poor quality of food, housing, and clothing, which stood in dramatic contrast to the prosperity of West Germany. Professionals in East Germany were watched for any sign of deviation from the party line; their privileges were at risk. The solution was to either comply or flee to West Germany, which was relatively easy before the crackdown and the Berlin wall of 1961.[19] Americans saw East Germany simply as a puppet of Moscow, with no independent possibilities.

Post-1990

During the early 1990s the reunified Germany was called a "partnership in leadership" as the U.S. emerged as the world's sole superpower.

Germany's effort to incorporate any major military actions into the slowly progressing European Security and Defence Policy did not meet the expectations of the U.S. during the Gulf War. After the September 11 attacks, German-American political relations were strengthened in an effort to combat terrorism, and Germany sent troops to Afghanistan as part of the NATO force. Yet, discord continued over the Iraq War, when then German chancellor Gerhard Schröder and foreign minister Joschka Fischer made efforts to prevent war and consequently did not join the U.S. and UK led multinational force in Iraq.[20][21]

21st century

In response to the 2013 mass surveillance disclosures, Germany cancelled the 1968 intelligence sharing agreement with the USA and UK.[22]

In July 2014, two Bundesnachrichtendienst officials were arrested by federal prosecutors for allegedly spying on the German government for the C.I.A.. Chancellor Angela Merkel asked the coordinator of CIA activity at Berlin's U.S. Embassy to leave his diplomatic post.[23] In response to the arrests, Merkel said, "Viewed with good common sense, spying on friends and allies is a waste of energy. In the cold war it may have been the case that there was mutual mistrust. Today we live in the 21st century."[24] The arrests followed the revelation that the NSA tapped the chancellor's cellphone.[25] German attempts to be included in the non-spying pact the US has with the UK, New Zealand, Australia and Canada were fruitless.[26] Merkel on 18 July 2014 said trust could only be restored through talks and Germany would seek to have such talks. She reiterated the U.S. was Germany's most important ally, and nothing about their relationship would change.[27] Nevertheless German government officials in Berlin strengthened counterintelligence and planned new security measures in anticipation of prolonged frosty relations with the United States.[28] On 16 August 2014, Der Spiegel, quoting unnamed sources, reported Germany had monitored telephone calls involving U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, and former secretary Hillary Clinton.[29]

Military relations

German-American military relations date back to the American War of Independence when German troops fought on both sides. Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, a former Captain in the Prussian Army, was appointed Inspector General of the Continental Army and helped form the rough militia into a proper military force during the winter of 1777–1778 at Valley Forge. Von Steuben is considered to be one of the founding fathers of the United States Army.

Another German that served during the American Revolution was Major General Johann de Kalb, who served under Horatio Gates at the Battle of Camden and died as a result of several wounds he sustained during the fighting.

About 30,000 German mercenaries fought for the British, with 17,000 coming from Hesse, amounting to about one in four of the adult male population of the principality. Generally referred to as Hessians, these German auxiliaries swore allegiance to the British Crown, but without renouncing their allegiance to their own rulers. Leopold Philip de Heister, Wilhelm von Knyphausen, and Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg were the principal generals who commanded these troops with Frederick Christian Arnold, Freiherr von Jungkenn as the senior German officer.[30]

German Americans have been very influential in the United States military. Some notable figures include Brigadier General August Kautz, Major General Franz Sigel, General of the Armies John J. Pershing, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, and General Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr..

Germany and the United States are joint NATO members. The U.S. currently has approximately 50,000 American troops stationed in southern Germany. During the Cold War the number of U.S. troops based in West Germany was much higher. Both nations have cooperated closely in the War on Terror, with Germany providing more troops than any other nation. The two nations; however, have opposing public policy positions in the War in Iraq. While Germany may have blocked U.S. efforts to secure UN Resolutions in the buildup to war, they continued to support U.S. interests in southwest Asia quietly. German soldiers operated military biological and chemical cleanup equipment at Camp Doha in Kuwait; German Navy ships secured sea lanes to deter attacks by Al Qaeda on U.S. Forces and equipment in the Persian Gulf; and soldiers from Germany's Bundeswehr deployed all across southern Germany to U.S. Military Bases to conduct Force Protection duties in place of German-based U.S. Soldiers who were deployed to the Iraq War. The latter mission lasted from 2002 until 2006. As of 2006 nearly all these Bundeswehr have been demobilized.[31]

The United States established a permanent military presence in Germany during the Second World War that continued throughout the Cold War and then was drawn down in the early 21st Century, with the last American tanks withdrawn from Germany in 2013.[32] The American tanks returned the next year, when the gap in multinational training opportunities was noticed.[33]

Cultural relations

Karl May was a prolific German writer who specialized in writing Westerns. Although he only visited America once towards the end of his life, May provided Germany with a series of frontier novels, which provided Germans with an imaginary view of America.

Famous German-American architects, artist, musicians and writers:

- Josef Albers

- Albert Bierstadt, known for his lavish, sweeping landscapes of the American West

- Philip K. Dick, writer

- Walter Gropius, architect

- Albert Kahn, architect

- Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, architect

- Paul Hindemith, composer

- Philip Johnson

- Otto Klemperer, conductor

- Henry Miller, writer

- Les Paul, guitarist

- Carl Schurz

- Dr. Seuss

- Alfred Stieglitz, photographer

- Kurt Vonnegut

German takes third place after Spanish and French among the foreign languages taught at American secondary schools, colleges and universities. Conversely, nearly half of the German population can speak English well.

Research and academic exchange

The contributions of German and American scientists to various fields of science are numerous. The cooperation between academics from both countries is extensive. Since the middle of the 20th century, German scientists have provided invaluable contributions to American technological advancement. For example, Wernher von Braun, who built the German V-2 rockets and his team of scientists came to the United States and were central in building the American space exploration program.[35]

Researchers at German and American universities run various exchange programs and projects, and focus on space exploration, the International Space Station, environmental technology, and medical science. Import cooperations are also in the fields of biochemistry, engineering, information and communication technologies and life sciences (networks through: Bacatec, DAAD). The United States and Germany signed a bilateral Agreement on Science and Technology Cooperation in February 2010.[36]

American cultural institutions in Germany

In the post-war era, a number of institutions, devoted to highlighting American culture and society in Germany, were established and are in existence today, especially in the south of Germany, the area of the former U.S. Occupied Zone. Today, they offer English courses as well as cultural programs.

Diplomatic missions

- Embassy of the United States in Berlin

- Embassy of Germany in Washington

- The Congressional Study Group on Germany via United States Association of Former Members of Congress

See also

- German Americans

- German in the United States

- German interest in the Caribbean

References

- ↑ http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/diplo/en/Laender/UnitedStates.html

- ↑ Gebauer, Matthias (10 July 2014). "Retaliation for Spying: Germany Asks CIA Official to Leave Country". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ "United States". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ Smith, Claire M. (August 2010). "These are our Numbers: Civilian Americans Overseas and Voter Turnout" (PDF). OVF Research Newsletter 2 (4): 4.

- ↑ http://www.scribd.com/doc/5207716/Budget-Difesa-ITALIA-2008.

- ↑ http://www.gpoaccess.gov/usbudget/fy10/pdf/budget/defense.pdf

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau (2000)

- ↑ The Nuremberg Laws by Ben S. Austin

- ↑ "'The Ugly German' and 'The Ugly American': National Stereotypes of the Modern Conformist,", by Todd Hanlin, paper delivered to the American Association of Teachers of German and Modern Language Association of Philadelphia and Vicinity, West Chester, 1979.

- ↑ http://www.globescan.com/commentary-and-analysis/press-releases/press-releases-2013/277-views-of-china-and-india-slide-while-uks-ratings-climb.html

- ↑ Perceptions Of Germany & The Germans Among The U.S. Population (April 17, 2007).

- ↑ German Opinion of the U.S.

- ↑ David H. Olivier (2004). German Naval Strategy, 1856-1888: Forerunners to Tirpitz. Routledge. p. 87.

- ↑ Dirk Bönker (2012). Militarism in a Global Age: Naval Ambitions in Germany and the United States before World War I. Cornell U.P. p. 61.

- ↑ Lester D. Langley (1983). The Banana Wars: United States Intervention in the Caribbean, 1898-1934. p. 14.

- ↑ Edmund Morris, "'A Matter Of Extreme Urgency' Theodore Roosevelt, Wilhelm II, and the Venezuela Crisis of 1902," Naval War College Review (2002) 55#2 pp 73-85

- ↑ Friedrich Katz, Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States and the Mexican Revolution (1981) pp 50-64

- ↑ Ruud van Dijk et al. (2013). Encyclopedia of the Cold War. Routledge. pp. 414–15.

- ↑ Rainer Schnoor, "The Good and the Bad America: Perceptions of the United States in the GDR," in Detlef Junker, et al. eds. The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War, 1945-1968: A Handbook, Vol. 2: 1968-1990 (2004) pp 618626, quotation on page 619.

- ↑ Wiegrefe, Klaus (24 November 2010). "Classified Papers Prove German Warnings to Bush". Spiegel Online. Translated by Josh Ward. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Joschka Fischer interviewed by Gero von Boehm; originally broadcast on 3Sat in 2010; version with English subtitles on YouTube

- ↑ "Germany ends spy pact with US and UK after Snowden."

- ↑ Philip J. Crowley (11 July 2014). "PJ Crowley: US-German relations have 'Groundhog Day'". News US & Canada (BBC).

- ↑ Oltermann, Phillip; Ackerman, Spencer (10 July 2014). "Germany asks top US intelligence official to leave country over spy row". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ Sullivan, Sean (8 July 2014). "Hillary Clinton ‘sorry’ that Merkel’s phone was tapped". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ "Germany expels CIA official in US spy row". News/Europe (BBC). 10 July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ↑ "Sensible talks urged by Merkel to restore trust with US". Germany News.Net. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ↑ Melanie Amann, Blome, Gebauer, Nelles, Repinski, Schindler & Weiland (July 22, 2014). "Keeping Spies Out: Germany Ratchets Up Counterintelligence Measures". Der Spiegel Online. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ↑ "Hillary Clinton and John Kerry reportedly spied on by German". Europe Sun. 17 August 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ↑ Freiherr von Jungkenn Papers

- ↑ Gordon, Michael and Trainor, Bernard "Cobra II: The Inside Story of the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq" New York: 2006 ISBN 0-375-42262-5

- ↑ "US Army's last tanks depart from Germany."

- ↑ Darnell, Michael S. (31 January 2014). "American tanks return to Europe after brief leave". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ↑ Economic relations between Germany and the United States are largely untroubled. The Transatlantic Economic Partnership between the U.S. and the EU, which was launched in 2007 on Germany’s initiative, and the subsequently created Transatlantic Economic Council open up additional opportunities. The U.S. is Germany’s principal trading partner outside the EU and Germany is the U.S.’s most important trading partner in Europe. In terms of the total volume of U.S. bilateral trade (imports and exports), Germany remains in fifth place, behind Canada, China, Mexico and Japan. The U.S. ranks fourth among Germany’s trading partners, after the Netherlands, China and France. At the end of 2013, bilateral trade was worth $162 billion. Germany and the U.S. are important to each other as investment destinations. At the end of 2012, bilateral investment was worth $320 billion, German direct investment in the U.S. amounting to $199 billion and U.S. direct investment in Germany $121 billion. At the end of 2012, U.S. direct investment in Germany stood at approximately $121 billion, an increase of nearly 14 per cent compared with the previous year (approximately $106 billion). During the same period, German direct investment in the U.S. amounted to some $199 billion, below the previous year’s level (approximately $215 billion). Germany is the eighth largest foreign investor in the U.S., after the United Kingdom, Japan, the Netherlands, Canada, France, Switzerland and Luxembourg, and ranks eleventh as a destination for U.S. foreign direct investment.

- ↑ Michael Neufeld (2008). Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War. Random House Digital, Inc.

- ↑ Dolan, Bridget M. (December 10, 2012). "Science and Technology Agreements as Tools for Science Diplomacy". Science & Diplomacy 1 (4).

Bibliography

- Bönker, Dirk (2012). Militarism in a Global Age: Naval Ambitions in Germany and the United States before World War I. Cornell U.P.

- Dallek Robert. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy (Oxford University Press, 1979)

- Gatzke, Hans W. Germany and the United States: A "Special Relationship?" (Harvard University Press, 1980)

- Gienow-Hecht, Jessica C. E. "Trumpeting Down the Walls of Jericho: The Politics of Art, Music and Emotion in German-American Relations, 1870-1920," Journal of Social History (2003) 36#3

- Link, Arthur S. Wilson: The Struggle for Neutrality, 1914-1915 (Princeton University Press, 1960)

- Offner, Arnold A. American Appeasement: United States Foreign Policy and Germany, 1933-1938 (Harvard University Press, 1969) online edition

- Schwabe, Klaus "Anti-Americanism within the German Right, 1917-1933," Amerikastudien/American Studies (1976) 21#1 pp 89–108.

- Schwabe, Klaus. Woodrow Wilson, Revolutionary Germany, and Peacemaking, 1918-1919 (U. of North Carolina Press, 1985.)

- Trommler, Frank and Joseph McVeigh, eds. America and the Germans: An Assessment of a Three-Hundred-Year History (2 vol. U of Pennsylvania Press, 1990) vol 2 online

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany (2 vols. (1980)

After 1941

- Backer, John H. The Decision to Divide Germany: American Foreign Policy in Transition (1978)

- Bark, Dennis L. and David R. Gress. A History of West Germany Vol 1: From Shadow to Substance, 1945-1963 (1989); A History of West Germany Vol 2: Democracy and Its Discontents 1963-1988 (1989), the standard scholarly history in English

- Junker, Detlef, et al. eds. The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War, 1945-1968: A Handbook, Vol. 1: 1945-1968; (2004) excerpt and text search; Vol. 2: 1968-1990 (2004) excerpt and text search, comprehensive coverage

- Gimbel John F. American Occupation of Germany (Stanford UP, 1968)

- Hanrieder Wolfram. West German Foreign Policy, 1949-1979 (Westview, 1980)

- Höhn, Maria H. GIs and Frèauleins: The German-American Encounter in 1950s West Germany (U of North Carolina Press, 2002)

- Immerfall, Stefan. Safeguarding German-American Relations in the New Century: Understanding and Accepting Mutual Differences (2006)

- Kuklick, . Bruce. American Policy and the Division of Germany: The Clash with Russia over Reparations (Cornell University Press, 1972)

- Ninkovich, Frank. Germany and the United States: The Transformation of the German Question since 1945 (1988)

- Nolan, Mary. "Anti-Americanism and Americanization in Germany." Politics & Society (2005) 33#1 pp 88–122.

- Pettersson, Lucas. "Changing images of the USA in German media discourse during four American presidencies." International Journal of Cultural Studies (2011) 14#1 pp 35–51.

- Pommerin, Reiner. The American Impact on Postwar Germany (Berghahn Books, 1995) online edition

- Smith Jean E. Lucius D. Clay (1990)

- Stephan, Alexander, ed. Americanization and anti-Americanism: the German encounter with American culture after 1945 (Berghahn Books, 2013)

External links

- History of Germany - U.S. relations

- American Academy in Berlin

- American Chamber of Commerce in Germany

- AICGS American Institute for Contemporary German Studies in Washington, D.C.

- American Council on Germany

- Amerikahaus in Munich

- Aspen Institute Berlin

- Atlantische Akademie Rheinland-Pfalz e.V.

- Atlantik Brücke Berlin

- Atlantic Review

- The Atlantic Times

- DAAD New York

- German Marshall Fund of the United States in Washington, D.C.

- Germany-USA Career Center for German American Trade

- Munich Conference on Security Policy

- German-American Institute Tübingen

- German-American Center (James F. Byrnes Institute) Stuttgart (German)

- German-American Heritage Foundation of the USA in Washington, D.C.

- German-American Friendship Club - US Army Garrison Hohenfels

- Embassies

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.png)

.svg.png)