Germany–United Kingdom relations

|

|

Germany |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

Germany–United Kingdom relations, or Anglo-German relations, are the bilateral relations between the United Kingdom and Germany.

Before the unification of Germany in 1871, Britain was often allied in wartime with Prussia. The royal families often intermarried. The "Hanoverian kings" were also the rulers (1714-1837) of the small German state of Hanover. They ruled both countries from London.

Historians have long focused on the diplomatic and naval rivalries between Britain and Germany in the period after 1871, searching for the root causes of the growing antagonism that led to the First World War. In recent years historians have paid greater attention to the mutual cultural influences and the transfer of ideas and technologies, as well as industry, trade, and science.[1]

During the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), some of the German states at times supported France against Britain. Britain and Germany fought against each other in two wars, World War I and World War II. After British occupation of part of West Germany, 1945–50, they became close allies in NATO, and now with the former East Germany as well. Trade relations have been very strong since the late Middle Ages, when the German cities of the Hanseatic League traded with England and Scotland. Both nations are active in the EU, with Germany the dominant nation within the Union and Britain a more reluctant member that never adopted the Euro.

Country comparison

| |

| |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 81,757,600 | 62,041,708 |

| Area | 357,021 km2 (137,847 sq mi) | 244,820 km2 (94,526 sq mi ) |

| Population density | 229/km2 (593/sq mi) | 246/km2 (637/sq mi) |

| Capital | Berlin | London |

| Largest city | Berlin – 3,439,100 (4,900,000 Metro), (Rhine-Ruhr 12,190,000 metro) | London – 7,556,900 (13,945,000 Metro) |

| Government | Federal parliamentary constitutional republic | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| Official languages | German (de facto and de jure) | English (de facto) |

| Main religions | 67.07% Christianity, 29.6% non-religious, 3.7% Islam, 0.25% Buddhism, 0.25% Judaism, 0.1% Hinduism, 0.09% Sikhism |

59.3% Christianity, 25.1% non-religious, 7.2% unstated, 4.8% Islam, 1.5% Hinduism, 0.8% Sikhism, 0.5% Judaism, 0.4% Buddhism |

| Ethnic groups | 91.5% German, 2.4% Turkish, 6.1% other[2] | 87.1% White, 7.0% Asian, 3% Black, 2% Mixed, 0.9% Other |

| GDP (nominal) | €2.936 trillion (US$3.66 trillion) €35,825 per capita ($44,660) | £1.695 trillion (US$2.674 trillion), £27,805 per capita ($43,875) |

| Expatriate populations | 266,000 German-born people live in the UK | 250,000 British-born people live in Germany |

| Military expenditures | €37.5 billion (US$46.8 billion) (FY 2008)[3] | £41 billion (US$65 billion) (FY 2009–10)[4] |

History

The Celtic Church established missionary activities in mainland Europe, including what is now Germany. See Schottenkloster.

Shared heritage

English and German are both West Germanic languages. Modern English has diverged significantly from its continental sister languages, having received substantially more French and Latin influence and perhaps contact with the world outside Europe through trade and imperialism has also influenced English to a greater degree. However, English has its roots in the languages spoken by Germanic peoples from mainland Europe, more specifically various peoples came from what is now the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark, including a people called the Angles, after whom English is named. Many everyday words in English are of Germanic origin and are therefore similar to their German counterparts, while more intellectual and formal words are of French or Latin origin, also English is not the only native language spoken in Britain today (for examples Gaelic, Welsh and Cornish) and German is not the only native language spoken in Germany (for example Lower Sorbian and Upper Sorbian) but the shared origins of much of British and German language and culture are undeniable. Assertions of shared genetic heritage between the United Kingdom and Germany have been more difficult to quantify.

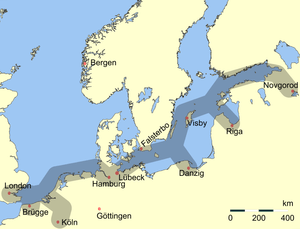

Trade and the Hanseatic League

There is a long history of trade relations between the Germans and the British. The Hanseatic League was a commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and their market towns that dominated trade along the coast of Northern Europe. It stretched from the Baltic to the North Sea during the 13th–17th centuries, and included London. The main centre was Lübeck, Germany. The Hanseatic League facilitated trade between London and numerous cities, most of them controlled by German merchants. It also opened up trade with the Baltic.[5]

Royal family

England's first diplomatic relations with Germany were through the dynastic alliance pursued between Æthelberht of Kent and Charibert I, and were significantly augmented later under Offa of Mercia and Charlemagne. Until the late 17th century such marriages between the two nations were only sporadic, due initially to the largely French preference of the House of Wessex, when both the Anglo-Saxons and Franks continually had to contend with severe Danish and Norman Viking attacks and colonisations. Another reason for estrangement was Germany's increasing preoccupation with Italy: the two nations together formed the core Holy Roman Empire. Empress Matilda, the daughter of Henry I of England, was married between 1114 and 1125 to Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor, but they had no issue. She then married Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, and tried to usurp the kingdom of Stephen of England; her son became Henry II of England. In 1256, Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall, was elected King of Germany and his sons were surnamed Almain. Throughout this period, the Steelyard of London was a typical German community in England. German mercenaries were used in the Wars of the Roses.

Subsequently Anne of Cleves was the consort of Henry VIII. The Habsburg Philip II of Spain in 1554, was another consort of the English monarch of German stock. It was not until William III of England that a king of German origin came to reign, from the House of Nassau. The consort of his successor Queen Anne was Prince George of Denmark from the House of Oldenburg, who had no surviving children, yet a cadet dynastic successor in Mountbatten-Windsor today. Philip, William and George each failed to provide heirs for England and Britain.

In 1714, succeeding Queen Anne, George I, a German-speaking Hanoverian prince of mixed British and German descent, ascended to the British throne, founding the House of Hanover. This was descended from the Wittelsbachs who descended from Elizabeth of Bohemia. For over a century, Britain's monarchs were also rulers of Hanover (first as Prince Electors of the Holy Roman Empire, then as a separate Kingdom). This was a personal union rather than a political one, with the two countries remaining quite separate. Hanover was occupied during the Napoleonic wars, but some Hanoverian troops fled to the United Kingdom to form the King's German Legion, a unit within the British army made up of ethnic Germans. The link between the two kingdoms finally ended in 1837 with the accession of Queen Victoria to the British throne: under the Salic Law women were ineligible for the throne of Hanover.

Every British monarch from George I to George V in the 20th century took a Royal German consort. The British Royal family retained the German surname von Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha until 1917, when, in response to anti-German feelings during World War I, it was legally changed to the more British "Windsor". In the same year, members of the British Royal family members gave up any German titles they held, whilst their German relatives were stripped of any British titles they held by an Act of Parliament.

Intellectual influences

Ideas flowed back and forth between the two nations.[1] Refugees from Germany's repressive regimes often settled in Britain, most notably Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Advances in technology were shared, as in chemistry.[6] Over a hundred thousand German immigrants also came to Britain. Germany was perhaps one of the world's main centres for innovative social ideas in the late 19th and early 20th century. The British around 1910, led by the Liberals Asquith and Lloyd George, adopted Bismarck's system of social welfare.[7] Ideas on town planning were exchanged.[8]

1870–1919

The British Foreign Office had been poorly served by a series of ambassadors who provided only superficial reports on the dramatic developments of the 1860s. That changed with the appointment of Odo Russell (1871-1884), who developed a close rapport with Bismarck and who provided in depth coverage of German developments.[9]

Britain gave passive support to the unification of Germany under Prussian auspices for strategic and ideological reasons as well as business advantages. In terms of strategy, the rise of the German Empire meant there was a counterbalance on the continent to both France and Russia, the two powers that troubled Britain the most. The threat from France and the Mediterranean, and from Russia and Central Asia, could be neutralised by judicious relationships with Germany. The new nation would be a stabilising force, and Bismarck especially emphasised his role in stabilising Europe and preventing any major war on the continent. Gladstone, however, was always suspicious of Germany, and disliked its authoritarianism; he feared that sooner or later Germany would make war on a weaker neighbour.[10] The ideological gulf was stressed by Lord Arthur Russell in 1872:

- Prussia now represents all that is most antagonistic to the liberal and democratic ideas of the age; military despotism, the rule of the sword, contempt for sentimental talk, indifference to human suffering, imprisonment of independent opinion, transfer by force of unwilling populations to a hateful yoke, disregard of European opinion, total want of greatness and generosity, etc., etc."[11]

Britain was looking inward and avoided picking any disputes with Germany, although it did make clear in the "war in sight" crisis of 1875 that it would not tolerate a pre-emptive German war on France.[12]

Under the leadership of German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, a complex network of European alliances kept the peace in the 1870s and 1880s. The British were building up their empire, but Bismarck strongly opposed colonies as too expensive. When public demand forced him in the 1880s to grab colonies in Africa and the Pacific, conflicts with Britain were minimal.[13]

Coming to power in 1888, the young Kaiser Wilhelm dismissed Chancellor Bismarck in 1890 and sought aggressively to increasing Germany's influence in the world through his Weltpolitik. Foreign policy was controlled by the erratic Kaiser, who played an increasingly reckless hand,[14] and by the powerful foreign office under the leadership of Friedrich von Holstein.[15] The foreign office in Berlin argued that: first, a long-term coalition between France and Russia had to fall apart; secondly, Russia and Britain would never get together; and, finally, Britain would eventually seek an alliance with Germany. Germany refused to renew its treaties with Russia. But Russia did form a closer relationship with France in the Dual Alliance of 1894, since both were worried about the possibilities of German aggression. London refused to agree to the formal alliance that Germany sought. Berlin's analysis proved mistaken on every point, leading to Germany's increasing isolation and its dependence on the Triple Alliance, which brought together Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. The Triple Alliance was undermined by differences between Austria and Italy, and in 1915 Italy switched sides.[16]

Naval race

The British Royal Navy dominated the globe in the 19th century, but after 1890 Germany worked to achieve parity. It never did catch up, but the resulting naval race heightened tensions between the two nations.[17][18]

The German Navy under Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz had ambitions to rival the great British Navy, and dramatically expanded its fleet in the early 20th century to protect the colonies and exert power worldwide.[19] Tirpitz started a programme of warship construction in 1898. In 1890, Germany traded the strategic island of Heligoland in the North Sea with Britain in exchange for the eastern African island of Zanzibar, and proceeded to construct a great naval base there. The British, however, kept well ahead in the naval race by the introduction of the highly advanced new Dreadnought battleship in 1907.[20]

Moroccan crisis

In the First Moroccan Crisis of 1905, Germany nearly came to blows with Britain and France when the latter attempted to establish a protectorate over Morocco. The Germans were upset at having not been informed about French intentions, and declared their support for Moroccan independence. William II made a highly provocative speech regarding this. The following year, a conference was held in which all of the European powers except Austria-Hungary (by now little more than a German satellite) sided with France. A compromise was brokered by the United States where the French relinquished some, but not all, control over Morocco.[21]

Coming of the World War

In Germany left-wing parties, especially the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) made large gains in the 1912 German election. German government at the time was dominated by the Prussian Junkers (landed elites) who feared the rise of these left-wing parties. German historian Fritz Fischer famously argued that they deliberately sought an external war to distract the population and whip up patriotic support for the government.[22] Other scholars argue that German conservatives were ambivalent about a war, worrying that losing a war would have disastrous consequences, and even a successful war might alienate the population if it were lengthy or difficult.[23]

In explaining why neutral Britain went to war with Germany, Paul Kennedy, in The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860-1914 (1980) argued that it was critical for war that Germany become economically more powerful than Britain. Kennedy downplayed the disputes over economic trade imperialism, the Baghdad Railway, confrontations in Eastern Europe, high-charged political rhetoric and domestic pressure-groups. Germany's reliance time and again on sheer power, while Britain increasingly appealed to moral sensibilities, played a role, especially in seeing the invasion of Belgium as a necessary military tactic or a profound moral crime. The German invasion of Belgium was not important because the British decision had already been made and the British were more concerned with the fate of France.[24] Kennedy argues that by far the main reason was London's fear that a repeat of 1870—when Prussia and the German states smashed France—would mean Germany, with a powerful army and navy, would control the English Channel, and north-west France. British policy makers insisted that would be a catastrophe for British security.[25]

In 1839 Britain, Germany and other powers agreed on the Treaty of London to guarantee the neutrality of Belgium. Germany violated that treaty in 1914—calling it a "scrap of paper," so Britain declared war.[26]

British victory

Britain and the Allies won the World War, as Germany virtually surrendered in November, 1918. In the Khaki Election of 1918, coming days later, Prime Minister David Lloyd George promised to impose a harsh treaty on Germany. At the great Versailles Conference, however, Lloyd George took a much more moderate approach. France and Italy however demanded and achieved harsh terms, including forcing Germany to admit starting the war, and a demand that Germany pay the entire Allied cost of the war, including veterans' benefits and interest.[27]

Interwar period

In 1920–1933, Britain and Germany were on generally good terms, as shown by the Locarno Treaties[28] and Kellogg–Briand Pact which helped reintegrate Germany into Europe. At the Genoa conference in 1922, Britain clashed openly with France over the amount of reparations to be collected from Germany. In 1923 France occupied the Ruhr industrial area of Germany following German default in reparations. Britain condemned the French move, and largely supported Germany in the ensuring Ruhrkampf (Ruhr struggle) between the Germans and the French. In 1924 Britain forced France to make major concessions in regards to the amount of reparations Germany had to pay.[29]

With the coming to power of Hitler and the Nazis in 1933, relations turned tense. In 1934 a secret report by the Defence Requirements Committee identified Germany as the "ultimate potential enemy" and called for Continental expeditionary force of five mechanised divisions and fourteen infantry divisions. However, budget restraints prevented the formation of this large force.[30] In 1935 the two nations agreed to the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, designed to avoid a repeat of the pre-1914 naval race.[31]

By 1936 a policy of appeasement began under Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in an effort to prevent war, or at least postpone it until the British military was ready. Appeasement has been the subject of intense debate for seventy years among academics, politicians and diplomats. The historians' assessments have ranged from condemnation for allowing Hitler's Germany to grow too strong, to the judgement that he had no alternative and acted in Britain's best interests. At the time, these concessions were very popular and the Munich Pact in 1938 among Germany, Britain, France and Italy prompted Chamberlain to announce that he had secured "peace for our time".[32]

World War II

Nazi Germany and the United Kingdom fought each other during World War II, and this confrontation continues to loom large in the British public consciousness. War was brought to British skies in the Battle of Britain, but after their aerial assault was repulsed, the Germans postponed the planned invasion of Britain. Following D-Day, British forces contributed substantially to the defeat of Germany, and occupied part of it.

Since 1945

Occupation

As part of the Yalta and Potsdam agreements, Britain took control of its own sector in occupied Germany. It soon merged its sector with the American and French sectors, and that territory became the independent nation of West Germany in 1949. The British played a central role in the Nuremberg trials of major war criminals in 1946. In Berlin, the British, American, and French zones were joined into West Berlin, and the four occupying powers kept official control of the city until 1991.[33][34]

Much of Germany's industrial plant fell within the British zone and there was trepidation that rebuilding the old enemy's industrial powerhouse would eventually prove a danger to British security and compete with the battered British economy. One solution was to build up a strong free trade union movement in Germany. Another was to rely primarily on American money, through the Marshall Plan, that modernised both the British and German economies, and reduced traditional barriers to trade and efficiency. It was Washington, not London, that pushed Germany and France to reconcile and join together in the Schumann Plan of 1950 by which they agreed to pool their coal and steel industries.[35]

Cold War

With the United States taking the lead, Britain with its Royal Air Force played a major supporting role in providing food and coal to Berlin in the Berlin airlift of 1948–1949. The airlift broke the Soviet blockade which was designed to force the Western Allies out of the city.[36]

In 1955 West Germany joined NATO, while East Germany joined the Warsaw Pact. Britain at this point did not officially recognise East Germany. However the left wing of the Labour party, breaking with the anti-communism of the postwar years, called for it's recognition. This call heightened tensions between the British Labour Party and the German Social Democratic Party (SPD).[37]

After 1955, Britain decided to rely on relatively inexpensive nuclear weapons as a deterrent against the Soviet Union, and a way to reduce its very expensive troop commitments in West Germany. London gained support from Washington and went ahead with the reductions while insisting it was maintaining its commitment to the defence of Western Europe.[38]

Britain made two applications for membership in the Common Market (European Community). It failed in the face of the French veto in 1961, but was successful in 1967. The diplomatic support of West Germany proved decisive.

In 1962 Britain secretly assured Poland of its acceptance of the latter's western boundary. West Germany had been ambiguous about the matter. Britain had long been uneasy with West Germany's insistence on the provisional nature of the boundary. On the other hand it was kept secret so as not to antagonise Britain's key ally in its quest to enter the European Community.[39]

Reunification

.jpg)

In 1990, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher at first opposed German reunification, but eventually accepted the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany.[40]

Since 1945 Germany hosts several British military installations in Western part of the country as part of British Forces Germany. Both countries are members of the European Union and NATO, and share strong economic ties. David McAllister, the former minister-president of the German state of Lower Saxony, son of a Scottish father and a German mother, holds British and German citizenship.

In 1996, Britain and Germany established a shared embassy building in Reykjavik. Celebrations to open the building were held on 2 June 1996 and attended by the British Foreign Minister at the time, Malcolm Rifkind, and the then Minister of State at the German Foreign Ministry, Werner Hoyer, and the Icelandic Foreign Minister Halldór Ásgrímsson. The commemorative plaque in the building records that it is "the first purpose built co-located British-German chancery building in Europe".[41]

Twinnings

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

-

Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire and

Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire and  Regensburg, Bavaria

Regensburg, Bavaria -

Aberystwyth, Ceredigion and

Aberystwyth, Ceredigion and  Kronberg im Taunus, Hesse

Kronberg im Taunus, Hesse -

Abingdon, Oxfordshire and

Abingdon, Oxfordshire and  Schongau, Bavaria

Schongau, Bavaria -

Amersham, Buckinghamshire and

Amersham, Buckinghamshire and  Bensheim, Hesse

Bensheim, Hesse -

Ashford, Kent and

Ashford, Kent and  Bad Münstereifel, North Rhine-Westphalia

Bad Münstereifel, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Barking and Dagenham, London and

Barking and Dagenham, London and  Witten, North Rhine-Westphalia

Witten, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Barnsley, South Yorkshire and

Barnsley, South Yorkshire and  Schwäbisch Gmünd, Baden-Württemberg

Schwäbisch Gmünd, Baden-Württemberg -

Basingstoke, Hampshire and

Basingstoke, Hampshire and  Euskirchen, North Rhine-Westphalia

Euskirchen, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Bath, Somerset and

Bath, Somerset and  Braunschweig, Lower Saxony

Braunschweig, Lower Saxony -

Bedford, Bedfordshire and

Bedford, Bedfordshire and  Bamberg, Bavaria

Bamberg, Bavaria -

Belfast and

Belfast and  Bonn, North Rhine Westphalia

Bonn, North Rhine Westphalia -

Beverley, East Riding of Yorkshire and

Beverley, East Riding of Yorkshire and  Lemgo, North Rhine Westphalia

Lemgo, North Rhine Westphalia -

Birmingham and

Birmingham and  Frankfurt, Hesse

Frankfurt, Hesse -

Bolton, Greater Manchester and

Bolton, Greater Manchester and  Paderborn, North Rhine-Westphalia

Paderborn, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Bracknell, Berkshire and

Bracknell, Berkshire and  Leverkusen, North Rhine-Westphalia

Leverkusen, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Brentwood, Essex and

Brentwood, Essex and  Roth bei Nürnberg, Bavaria

Roth bei Nürnberg, Bavaria -

Bristol and

Bristol and  Hanover, Lower Saxony

Hanover, Lower Saxony -

Bromley, London and

Bromley, London and  Neuwied, Rhineland-Palatinate

Neuwied, Rhineland-Palatinate -

Cambridge, Cambridgeshire and

Cambridge, Cambridgeshire and  Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg

Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg -

Cardiff, South Glamorgan and

Cardiff, South Glamorgan and  Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg

Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg -

Carlisle, Cumbria and

Carlisle, Cumbria and  Flensburg, Schleswig-Holstein

Flensburg, Schleswig-Holstein -

Chelmsford, Essex and

Chelmsford, Essex and  Backnang, Baden-Württemberg

Backnang, Baden-Württemberg -

Chester, Cheshire and

Chester, Cheshire and  Lörrach, Baden-Württemberg

Lörrach, Baden-Württemberg -

Chesterfield, Derbyshire and

Chesterfield, Derbyshire and  Darmstadt, Hesse

Darmstadt, Hesse -

Christchurch, Dorset and

Christchurch, Dorset and  Aalen, Baden-Württemberg

Aalen, Baden-Württemberg -

Cirencester, Gloucestershire and

Cirencester, Gloucestershire and  Itzehoe, Schleswig-Holstein

Itzehoe, Schleswig-Holstein -

Cleethorpes, North East Lincolnshire and

Cleethorpes, North East Lincolnshire and  Königswinter, North Rhine-Westphalia

Königswinter, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Colchester, Essex and

Colchester, Essex and  Wetzlar, Hesse

Wetzlar, Hesse -

Coventry, West Midlands and

Coventry, West Midlands and  Dresden, Saxony, and Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein

Dresden, Saxony, and Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein -

Crawley, West Sussex and

Crawley, West Sussex and  Dorsten, North Rhine-Westphalia

Dorsten, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Darlington, County Durham and

Darlington, County Durham and  Mülheim an der Ruhr, North Rhine-Westphalia

Mülheim an der Ruhr, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Derby, Derbyshire and

Derby, Derbyshire and  Osnabrück, Lower Saxony

Osnabrück, Lower Saxony -

Dronfield, Derbyshire and

Dronfield, Derbyshire and  Sindelfingen, Baden-Württemberg

Sindelfingen, Baden-Württemberg -

Dundee and

Dundee and  Würzburg, Bavaria

Würzburg, Bavaria -

Ealing, London and

Ealing, London and  Steinfurt, North Rhine-Westphalia

Steinfurt, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Edinburgh and

Edinburgh and  Munich, Bavaria

Munich, Bavaria -

Elgin, Moray and

Elgin, Moray and  Landshut, Bavaria

Landshut, Bavaria -

Ellesmere Port, Cheshire and

Ellesmere Port, Cheshire and  Reutlingen, Baden-Württemberg

Reutlingen, Baden-Württemberg -

Enniskillen, County Fermanagh and

Enniskillen, County Fermanagh and  Brackwede, Bielefeld, North Rhine-Westphalia

Brackwede, Bielefeld, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Epping, Essex and

Epping, Essex and  Eppingen, Baden-Württemberg

Eppingen, Baden-Württemberg -

Felixstowe, Suffolk and

Felixstowe, Suffolk and  Wesel, North Rhine-Westphalia

Wesel, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Glasgow and

Glasgow and  Nuremberg, Bavaria

Nuremberg, Bavaria -

Glossop, Derbyshire and

Glossop, Derbyshire and  Bad Vilbel, Hesse

Bad Vilbel, Hesse -

Gloucester, Gloucestershire and

Gloucester, Gloucestershire and  Trier, Rhineland-Palatinate

Trier, Rhineland-Palatinate -

Greenwich, London and

Greenwich, London and  Reinickendorf, Berlin

Reinickendorf, Berlin -

Guildford, Surrey and

Guildford, Surrey and  Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg

Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg -

Halifax, West Yorkshire and

Halifax, West Yorkshire and  Aachen, North Rhine-Westphalia

Aachen, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Hammersmith and Fulham, London and

Hammersmith and Fulham, London and  Neukölln, Berlin

Neukölln, Berlin -

Hartlepool, County Durham and

Hartlepool, County Durham and  Hückelhoven, North Rhine-Westphalia

Hückelhoven, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Havering, London and

Havering, London and  Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Rhineland-Palatinate

Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Rhineland-Palatinate -

Hemel Hempstead and Dacorum, Hertfordshire and

Hemel Hempstead and Dacorum, Hertfordshire and  Neu Isenburg, Hesse

Neu Isenburg, Hesse -

High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire and

High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire and  Kelkheim, Hesse

Kelkheim, Hesse -

Hillingdon, London and

Hillingdon, London and  Schleswig, Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig, Schleswig-Holstein -

Kendal, Cumbria and

Kendal, Cumbria and  Rinteln, Lower Saxony

Rinteln, Lower Saxony -

Kettering, Northamptonshire and

Kettering, Northamptonshire and  Lahnstein, Rhineland-Palatinate

Lahnstein, Rhineland-Palatinate -

Kidderminster, Worcestershire and

Kidderminster, Worcestershire and  Husum, Schleswig-Holstein

Husum, Schleswig-Holstein -

Kilmarnock, Ayrshire and

Kilmarnock, Ayrshire and  Kulmbach, Bavaria

Kulmbach, Bavaria -

King's Lynn, Norfolk and

King's Lynn, Norfolk and  Emmerich am Rhein, North Rhine-Westphalia

Emmerich am Rhein, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Kirkcaldy, Fife and

Kirkcaldy, Fife and  Ingolstadt, Bavaria

Ingolstadt, Bavaria -

Knaresborough, North Yorkshire and

Knaresborough, North Yorkshire and  Bebra, Hesse

Bebra, Hesse -

Lancaster, Lancashire and

Lancaster, Lancashire and  Rendsburg, Schleswig-Holstein

Rendsburg, Schleswig-Holstein -

Leeds, West Yorkshire and

Leeds, West Yorkshire and  Dortmund, North Rhine-Westphalia

Dortmund, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Leicester, Leicestershire and

Leicester, Leicestershire and  Krefeld, North Rhine-Westphalia

Krefeld, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Leven, Fife and

Leven, Fife and  Holzminden, Lower Saxony

Holzminden, Lower Saxony -

Lichfield, Staffordshire and

Lichfield, Staffordshire and  Limburg an der Lahn, Hesse

Limburg an der Lahn, Hesse -

Lincoln, Lincolnshire and

Lincoln, Lincolnshire and  Neustadt an der Weinstraße, Rhineland-Palatinate

Neustadt an der Weinstraße, Rhineland-Palatinate -

Littlehampton, West Sussex and

Littlehampton, West Sussex and  Durmersheim, Baden-Württemberg

Durmersheim, Baden-Württemberg -

Liverpool and

Liverpool and  Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia

Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia -

London and

London and  Berlin

Berlin -

Luton, Bedfordshire and

Luton, Bedfordshire and  Bergisch-Gladbach, North Rhine-Westphalia

Bergisch-Gladbach, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Manchester and

Manchester and  Chemnitz, Saxony

Chemnitz, Saxony -

Margate, Kent and

Margate, Kent and  Idar-Oberstein, Rhineland-Palatinate

Idar-Oberstein, Rhineland-Palatinate -

Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire and

Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire and  Oberhausen, North Rhine-Westphalia

Oberhausen, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire and

Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire and  Bernkastel-Kues, Rhineland-Palatinate

Bernkastel-Kues, Rhineland-Palatinate -

Motherwell, Lanarkshire and

Motherwell, Lanarkshire and  Schweinfurt, Bavaria

Schweinfurt, Bavaria -

Newcastle upon Tyne, Tyne and Wear and

Newcastle upon Tyne, Tyne and Wear and  Gelsenkirchen, North Rhine-Westphalia

Gelsenkirchen, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Norwich, Norfolk and

Norwich, Norfolk and  Koblenz, Rhineland-Palatinate

Koblenz, Rhineland-Palatinate -

Nottingham, Nottinghamshire and

Nottingham, Nottinghamshire and  Karlsruhe, Baden-Württemberg

Karlsruhe, Baden-Württemberg -

Nuneaton and Bedworth, Warwickshire and

Nuneaton and Bedworth, Warwickshire and  Cottbus, Brandenburg

Cottbus, Brandenburg -

Oakham, Rutland and

Oakham, Rutland and  Barmstedt, Schleswig-Holstein

Barmstedt, Schleswig-Holstein -

Oxford, Oxfordshire and

Oxford, Oxfordshire and  Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia

Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Perth, Perth and Kinross and

Perth, Perth and Kinross and  Aschaffenburg, Bavaria

Aschaffenburg, Bavaria -

Peterlee, County Durham and

Peterlee, County Durham and  Nordenham, Lower Saxony

Nordenham, Lower Saxony -

Portsmouth, Hampshire and

Portsmouth, Hampshire and  Duisburg, North Rhine-Westphalia

Duisburg, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Reading, Berkshire and

Reading, Berkshire and  Düsseldorf, North Rhine-Westphalia

Düsseldorf, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Richmond upon Thames, London and

Richmond upon Thames, London and  Konstanz, Baden-Württemberg

Konstanz, Baden-Württemberg -

Rossendale, Lancashire and

Rossendale, Lancashire and  Bocholt, North Rhine-Westphalia

Bocholt, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent and

Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent and  Wiesbaden, Hesse

Wiesbaden, Hesse -

Sheffield, South Yorkshire and

Sheffield, South Yorkshire and  Bochum, North Rhine-Westphalia

Bochum, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Skipton, North Yorkshire and

Skipton, North Yorkshire and  Simbach am Inn, Bavaria

Simbach am Inn, Bavaria -

Solihull, West Midlands and

Solihull, West Midlands and  Main-Taunus-Kreis, Hesse

Main-Taunus-Kreis, Hesse -

South Tyneside, Tyne and Wear and

South Tyneside, Tyne and Wear and  Wuppertal, North Rhine-Westphalia

Wuppertal, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Spalding, Lincolnshire and

Spalding, Lincolnshire and  Speyer, Rhineland-Palatinate

Speyer, Rhineland-Palatinate -

St. Helens, Merseyside and

St. Helens, Merseyside and  Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg

Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg -

Stafford, Staffordshire and

Stafford, Staffordshire and  Dreieich, Hesse

Dreieich, Hesse -

Stevenage, Hertfordshire and

Stevenage, Hertfordshire and  Ingelheim am Rhein, Bielefeld, Rhineland-Palatinate

Ingelheim am Rhein, Bielefeld, Rhineland-Palatinate -

Stockport, Greater Manchester and

Stockport, Greater Manchester and  Heilbronn, Baden-Württemberg

Heilbronn, Baden-Württemberg -

Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire and

Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire and  Erlangen, Bavaria

Erlangen, Bavaria -

Sunderland, Tyne and Wear and

Sunderland, Tyne and Wear and  Essen, North Rhine-Westphalia

Essen, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Sutton, London and

Sutton, London and  Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf, Berlin, and Minden, North Rhine-Westphalia

Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf, Berlin, and Minden, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Swansea, West Glamorgan and

Swansea, West Glamorgan and  Mannheim, Baden-Württemberg

Mannheim, Baden-Württemberg -

Todmorden, West Yorkshire and

Todmorden, West Yorkshire and  Bramsche, Lower Saxony

Bramsche, Lower Saxony -

Torbay, Devon and

Torbay, Devon and  Hamelin, Lower Saxony

Hamelin, Lower Saxony -

Thurso, Caithness and

Thurso, Caithness and  Brilon, North Rhine-Westphalia

Brilon, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Truro, Cornwall and

Truro, Cornwall and  Boppard, North Rhine-Westphalia

Boppard, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Uckfield, East Sussex and

Uckfield, East Sussex and  Quickborn, Pinneberg, Schleswig-Holstein

Quickborn, Pinneberg, Schleswig-Holstein -

Ware, Hertfordshire and

Ware, Hertfordshire and  Wülfrath, North Rhine-Westphalia

Wülfrath, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Wellingborough, Northamptonshire and

Wellingborough, Northamptonshire and  Wittlich, Rhineland-Palatinate

Wittlich, Rhineland-Palatinate -

Weston-super-Mare, North Somerset and

Weston-super-Mare, North Somerset and  Hildesheim, Lower Saxony

Hildesheim, Lower Saxony -

Weymouth, Dorset and

Weymouth, Dorset and  Holzwickede, North Rhine-Westphalia

Holzwickede, North Rhine-Westphalia -

Workington, Cumbria and

Workington, Cumbria and  Selm, North Rhine-Westphalia

Selm, North Rhine-Westphalia -

York, North Yorkshire and

York, North Yorkshire and  Münster, North Rhine-Westphalia

Münster, North Rhine-Westphalia

See also

- Timeline of British diplomatic history

- France–Germany relations

- Anglo-German Fellowship

- German migration to the United Kingdom

- Anglo-Prussian alliance

- Centre for Anglo-German Cultural Relations

- British Forces Germany

- Two World Wars and One World Cup

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dominik Geppert and Robert Gerwarth, eds. Wilhelmine Germany and Edwardian Britain: Essays on Cultural Affinity (2009).

- ↑ CIA. "CIA Factbook". Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑

- ↑ The Top 15 Military Spenders, 2008

- ↑ James Westfall Thompson, Economic and Social History of Europe in the Later Middle Ages (1300–1530) (1931) pp. 146–179.

- ↑ Johann Peter Murmann, "Knowledge and competitive advantage in the synthetic dye industry, 1850-1914: the coevolution of firms, technology, and national institutions in Great Britain, Germany, and the United States," Enterprise and Society (2000) 1#4, pp. 699–704.

- ↑ Ernest Peter Hennock, British social reform and German precedents: the case of social insurance, 1880-1914 (1987).

- ↑ Helen Meller, "Philanthropy and public enterprise: International exhibitions and the modern town planning movement, 1889–1913." Planning perspectives (1995) 10#3, pp. 295–310.

- ↑ Karina Urbach, Bismarck's Favourite Englishman: Lord Odo Russell's Mission to Berlin (1999) excerpt and text search

- ↑ Karina Urbach, Bismarck's Favorite Englishman (1999) ch 5

- ↑ Klaus Hilderbrand (1989). German Foreign Policy. Routledge. p. 21.

- ↑ Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise of Anglo-German Antagonism 1860-1914 (1980) pp 27-31

- ↑ Edward Ross Dickinson, "The German Empire: an Empire?" History Workshop Journal Issue 66, Autumn 2008 online in Project MUSE, with guide to recent scholarship

- ↑ On the Kaiser's "histrionic personality disorder", see Frank B. Tipton, A History of Modern Germany since 1815 (2003) pp 243–245.

- ↑ Röhl, J.C.G. (Sep 1966). "Friedrich von Holstein". Historical Journal 9 (3): 379–388. doi:10.1017/s0018246x00026716.

- ↑ Raff, Diethher (1988), History of Germany from the Medieval Empire to the Present, pp. 34–55, 202–206

- ↑ Paul Kennedy, The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism 1860–1914 (1980).

- ↑ Peter Padfield, The Great Naval Race: Anglo-German Naval Rivalry 1900-1914 (2005)

- ↑ Woodward, David (July 1963). "Admiral Tirpitz, Secretary of State for the Navy, 1897–1916". History Today 13 (8): 548–555.

- ↑ Herwig, Holger (1980). Luxury Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918.

- ↑ Esthus, Raymond A. (1970). Theodore Roosevelt and the International Rivalries. pp. 66–111.

- ↑ Fritz Fischer Germany's Aims in the First World War (1967).

- ↑ Ferguson, Niall The Pity of War (1999)

- ↑ Kennedy, The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860-1914 pp 457–462.

- ↑ Kennedy, The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860-1914, pp 464–470.

- ↑ Martin Gilbert (2004). The First World War: A Complete History. Macmillan. p. 32.

- ↑ Manfred F. Boemeke et al., eds. (1998). The Treaty of Versailles: A Reassessment after 75 Years. Cambridge U.P. p. 12.

- ↑ Frank Magee, "Limited Liability"? Britain and the Treaty of Locarno," Twentieth Century British History, (Jan 1995) 6#1, pp. 1–22.

- ↑ Sally Marks, "The Myths of Reparations," Central European History, (1978) 11#3, pp. 231–255.

- ↑ Keith Neilson; Greg Kennedy; David French (2010). The British Way in Warfare: Power and the International System, 1856-1956 : Essays in Honour of David French. Ashgate. p. 120.

- ↑ D.C. Watt, "The Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935: An Interim Judgement" Journal of Modern History, (1956) 28#2, pp. 155–175 in JSTOR

- ↑ Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (Manchester University Press, 1998).

- ↑ Barbara Marshall, "German attitudes to British military government 1945-47," Journal of contemporary History (1980) 15#4, pp. 655–684.

- ↑ Josef Becker, and Franz Knipping, eds., Great Britain, France, Italy and Germany in a Postwar World, 1945-1950 (Walter de Gruyter, 1986).

- ↑ Robert Holland, The Pursuit of Greatness: Britain and the World Role, 1900-1970 (1991), pp. 228–232.

- ↑ Avi Shlaim, "Britain, the Berlin blockade and the cold war", International Affairs (1983) 60#1, pp. 1–14.

- ↑ Stefan Berger, and Norman LaPorte, "Ostpolitik before Ostpo!itik: The British Labour Party and the German Democratic Republic (GDR), 1955-64," European History Quarterly (2006) 36#3, pp. 396–420.

- ↑ Saki Dockrill, "Retreat from the Continent? Britain's Motives for Troop Reductions in West Germany, 1955-1958," Journal of Strategic Studies (1997) 20#3, pp. 45–70.

- ↑ R. Gerald Hughes, "Unfinished Business from Potsdam: Britain, West Germany, and the Oder-Neisse Line, 1945–1962," International History Review (2005) 27#2, pp. 259–294.

- ↑ Vinen, Richard (2013). Thatcher's Britain: The Politics and Social Upheaval of the Thatcher Era. p. 3.

- ↑ "Embassy History". Internet Archive. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

Further reading

- Adams, R. J. Q. British Politics and Foreign Policy in the Age of Appeasement, 1935–1939 (1993)

- Bartlett, C. J. British Foreign Policy in the Twentieth Century (1989)

- Faber, David. Munich, 1938: Appeasement and World War II (2009) excerpt and text search

- Frederick, Suzanne Y. "The Anglo-German Rivalry, 1890-1914, pp 306-336 in William R. Thompson, ed. Great power rivalries (1999) online

- Geppert, Dominik, and Robert Gerwarth, eds. Wilhelmine Germany and Edwardian Britain: Essays on Cultural Affinity (2009)

- Görtemaker, Manfred. Britain and Germany in the Twentieth Century (2005)

- Hilderbrand, Klaus. German Foreign Policy from Bismarck to Adenauer (1989; reprint 2013), 272pp

- Hoerber, Thomas. "Prevail or perish: Anglo-German naval competition at the beginning of the twentieth century," European Security (2011) 20#1, pp. 65–79.

- Kennedy, Paul M. "Idealists and realists: British views of Germany, 1864–1939," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 25 (1975) pp: 137-56; compares the views of idealists (pro-German) and realists (anti-German)

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism 1860–1914 (London, 1980) excerpt and text search; influential synthesis

- Major, Patrick. "Britain and Germany: A Love-Hate Relationship?" German History, October 2008, Vol. 26 Issue 4, pp. 457–468.

- Massie, Robert K. Dreadnought: Britain, Germany and the Coming of the Great War (1991)

- Milton, Richard. Best of Enemies: Britain and Germany: 100 Years of Truth and Lies (2004), popular history covers 1845–1945 focusing on public opinion and propaganda; 368pp excerpt and text search

- Neville P. Hitler and Appeasement: The British Attempt to Prevent the Second World War (2005)

- Padfield, Peter. The Great Naval Race: Anglo-German Naval Rivalry 1900-1914 (2005)

- Palmer, Alan. Crowned Cousins: The Anglo-German Royal Connection (London, 1985).

- Ramsden, John. Don’t Mention the War: The British and the Germans since 1890 (London, 2006).

- Reynolds, David. Britannia Overruled: British Policy and World Power in the Twentieth Century (2nd ed. 2000) excerpt and text search, major survey of British foreign policy

- Rüger, Jan. The Great Naval Game: Britain and Germany in the Age of Empire (Cambridge, 2007).

- Rüger, Jan. "Revisiting the Anglo-German Antagonism," Journal of Modern History (2011) 83#3, pp. 579–617 in JSTOR

- Scully, Richard. British Images of Germany: Admiration, Antagonism, and Ambivalence, 1860–1914 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) 375pp

- Sontag, Raymond James. Germany and England : background of conflict, 1848-1898 (1938)

- Taylor, A. J. P. Struggle for Mastery of Europe: 1848–1918 (1954), comprehensive survey of diplomacy

- Urbach, Karina. Bismarck's Favourite Englishman: Lord Odo Russell's Mission to Berlin (1999) excerpt and text search

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany (2 vols. (1980)

Post 1941

- Bark, Dennis L., and David R. Gress. A History of West Germany. Vol. 1: From Shadow to Substance, 1945–1963. Vol. 2: Democracy and Its Discontents, 1963–1991 (1993), the standard scholarly history

- Berger, Stefan, and Norman LaPorte, eds. The Other Germany: Perceptions and Influences in British-East German Relations, 1945–1990 (Augsburg, 2005).

- Berger, Stefan, and Norman LaPorte, eds. Friendly Enemies: Britain and the GDR, 1949–1990 (2010) online review

- Deighton, Anne. The Impossible Peace: Britain, the Division of Germany and the Origins of the Cold War (Oxford, 1993)

- Dockrill, Saki. Britain's Policy for West German Rearmament, 1950-1955 (1991) 209pp

- Glees, Anthony. The Stasi files: East Germany's secret operations against Britain (2004)

- Hanrieder, Wolfram F. Germany, America, Europe: Forty Years of German Foreign Policy (1991)

- Heuser, Beatrice. NATO, Britain, France & the FRG: Nuclear Strategies & Forces for Europe, 1949-2000 (1997) 256pp

- Noakes, Jeremy et al. Britain and Germany in Europe, 1949–1990 * Macintyre, Terry. Anglo-German Relations during the Labour Governments, 1964-70: NATO Strategy, Détente and European Integration (2008)

- Mawby, Spencer. Containing Germany: Britain & the Arming of the Federal Republic (1999), p. 1. 244p.

- Smith, Gordon et al. Developments in German Politics (1992), pp. 137–86, on foreign policy

- Turner, Ian D., ed. Reconstruction in Postwar Germany: British Occupation Policy and the Western Zones, 1945–1955 (Oxford, 1992), 421pp.

- Zimmermann, Hubert. Money and Security: Troops, Monetary Policy & West Germany's Relations with the United States and Britain, 1950-1971 (2002) 275pp

External links

- Anglo-German Relations: Paul Joyce, University of Portsmouth

- Anglo-German Club in Hamburg

- Deutsch-Britische Gesellschaft in Berlin

- Anglo-German Foundation

- Anglo-German Trade

- British-German Association

- German-British Chamber of Industry & Commerce in London

- German Industry in the UK

- UK-German Connection

- British Embassy in Berlin

- German Embassy in London

- Centre for Anglo-German Cultural Relations

- News BBC - 'Thatcher's fight against German unity'

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||