Germanium dioxide

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Germanium dioxide | |||

| Other names

Germanium(IV) oxide Germania ACC10380 G-15 Germanium oxide Germanic oxide | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 1310-53-8 | |||

| ChemSpider | 14112 | ||

| |||

| Jmol-3D images | Image | ||

| PubChem | 14796 | ||

| RTECS number | LY5240000 | ||

| |||

| UNII | 5O6CM4W76A | ||

| Properties | |||

| GeO2 | |||

| Molar mass | 104.6388 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | white powder or colourless crystals | ||

| Density | 4.228 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 1,115 °C (2,039 °F; 1,388 K) | ||

| 4.47 g/L (25 °C) 10.7 g/L (100 °C) | |||

| Solubility | insoluble in HF, HCl soluble in other acid and alkali | ||

| Refractive index (nD) |

1.650 | ||

| Structure | |||

| Crystal structure | hexagonal | ||

| Hazards | |||

| EU Index | Not listed | ||

| Flash point | Non-flammable | ||

| LD50 (Median lethal dose) |

3700 mg/kg (rat, oral) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

| Other anions |

Germanium disulfide Germanium diselenide | ||

| Other cations |

Carbon dioxide Silicon dioxide Tin dioxide Lead dioxide | ||

| Related compounds |

Germanium monoxide | ||

| Except where noted otherwise, data is given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Germanium dioxide, also called germanium oxide and germania, is the inorganic compound with the chemical formula GeO2. It is the main commercial source of germanium. It also forms as a passivation layer on pure germanium in contact with atmospheric oxygen.

Structure

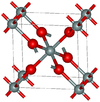

The two predominant polymorphs of GeO2 are hexagonal and tetragonal. Hexagonal GeO2 has the same structure as β-quartz, with germanium having coordination number 4. Tetragonal GeO2 (the mineral argutite) has the rutile-like structure seen in stishovite. In this motif, germanium has the coordination number 6. An amorphous (glassy) form of GeO2 is similar to fused silica.[1]

Germanium dioxide can be prepared in both crystalline and amorphous forms. At ambient pressure the amorphous structure is formed by a network of GeO4 tetrahedra. At elevated pressure up to approximately 9 GPa the germanium average coordination number steadily increases from 4 to around 5 with a corresponding increase in the Ge-O bond distance.[2] At higher pressures, up to approximately 15 GPa, the germanium coordination number increases to 6 and the dense network structure is composed of GeO6 octahedra.[3] When the pressure is subsequently reduced, the structure reverts to the tetrahedral form.[2][3] At high pressure, the rutile form converts to an orthorhombic CaCl2 form.[4]

Reactions

Heating germanium dioxide with powdered germanium at 1000 °C forms germanium monoxide (GeO).[1]

The hexagonal (d = 4.29 g/cm3) form of germanium dioxide is more soluble than the rutile (d = 6.27 g/cm3) form and dissolves to form germanic acid, H4GeO4 or Ge(OH)4.[5] GeO2 is only slightly soluble in acid but dissolves more readily in alkali to give germanates.[5]

In contact with hydrochloric acid, it releases the volatile and corrosive germanium tetrachloride.

Uses

The refractive index (1.7) and optical dispersion properties of germanium dioxide makes it useful as an optical material for wide-angle lenses and in optical microscope objective lenses. It is transparent in infrared.

A mixture of silicon dioxide and germanium dioxide ("silica-germania") is used as an optical material for optical fibers and optical waveguides.[6] Controlling the ratio of the elements allows precise control of refractive index. Silica-germania glasses have lower viscosity and higher refractive index than pure silica. Germania replaced titania as the silica dopant for silica fiber, eliminating the need for subsequent heat treatment, which made the fibers brittle.[7]

Germanium dioxide is also used as a catalyst in production of polyethylene terephthalate resin,[8] and for production of other germanium compounds. It is used as a feedstock for production of some phosphors and semiconductor materials.

Germanium dioxide is used in algaculture as an inhibitor of unwanted diatom growth in algal cultures, since contamination with the comparatively fast-growing diatoms often inhibits the growth of or outcompetes the original algae strains. GeO2 is readily taken up by diatoms and leads to silicon being substituted by germanium in biochemical processes within the diatoms, causing a significant reduction of the diatoms' growth rate or even their complete elimination, with little effect on non-diatom algal species. For this application, the concentration of germanium dioxide typically used in the culture medium is between 1 and 10 mg/l, depending on the stage of the contamination and the species.[9]

Toxicity and medical

Germanium dioxide has low toxicity, but in higher doses it is nephrotoxic.

Germanium dioxide is used as a germanium supplement in some questionable dietary supplements and "miracle cures".[10] High doses of these resulted in several cases of germanium poisonings.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0080379419.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 J W E Drewitt, P S Salmon, A C Barnes, S Klotz, H E Fischer, W A Crichton (2010). "Structure of GeO2 glass at pressures up to 8.6 GPa". Physical Review B 81: 014202. Bibcode:2010PhRvB..81a4202D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.81.014202.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 M Guthrie, C A Tulk, C J Benmore, J Xu, J L Yarger, D D Klug, J S Tse, H-k Mao, R J Hemley (2004). "Formation and Structure of a Dense Octahedral Glass". Physical Review Letters 93 (11): 115502. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..93k5502G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.115502. PMID 15447351.

- ↑ Structural evolution of rutile-type and CaCl2-type germanium dioxide at high pressure, J. Haines, J. M.Léger, C.Chateau, A. S.Pereira, Physics and Chemistry of Minerals, 27, 8 ,(2000), 575–582,doi:10.1007/s002690000092

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Egon Wiberg, Arnold Frederick Holleman, (2001) Inorganic Chemistry, Elsevier ISBN 0-12-352651-5

- ↑ Robert D. Brown, Jr. (2000). "Germanium" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey.

- ↑ Chapter Iii: Optical Fiber For Communications

- ↑ Thiele, Ulrich K. (2001). "The Current Status of Catalysis and Catalyst Development for the Industrial Process of Poly(ethylene terephthalate) Polycondensation". International Journal of Polymeric Materials 50 (3): 387–394. doi:10.1080/00914030108035115.

- ↑ Robert Arthur Andersen (2005). Algal culturing techniques. Elsevier Academic Press.

- ↑ Tao, S.H. and Bolger, P.M. (June 1997). "Hazard Assessment of Germanium Supplements". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 25 (3): 211–219. doi:10.1006/rtph.1997.1098. PMID 9237323.

| ||||||||||