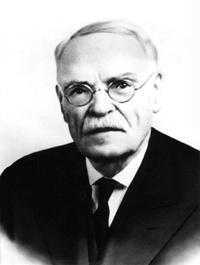

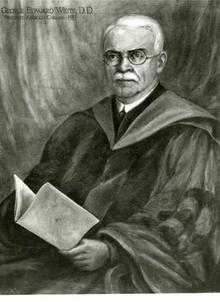

George E. White (missionary)

| George Edward White | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

October 14, 1861 Marash, Ottoman Empire |

| Died |

April 27, 1946 (aged 84) Claremont, California, United States |

| Occupation | Missionary, President of the Anatolia College, and witness to the Armenian Genocide |

George Edward White (October 14, 1861 – April 27, 1946) was an American Congregationalist missionary for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions for forty-three years. Stationed in the Ottoman Empire during the Armenian Genocide as President of the Anatolia College in Merzifon, White attempted to save the lives of many Armenians, including "refused to tell" where Armenians were hiding so to save them from getting deported or killed.[1] Thus he became an important witness to the Armenian Genocide.

Early life

On October 14, 1861, George Edward White was born in Marash, Ottoman Empire where his Christian missionary parents had arrived in 1856.[2] He then traveled to the United States to attend Iowa College in Grinnell, Iowa and marry. Deciding upon a pastoral career, White then attended the Hartford Theological Seminary during the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878) and continued his education at Oxford University in England.[2] Upon returning to Iowa, he received a Doctor of Divinity degree from Grinnell College.[2]

For three years, George E. White served as pastor of a local Congregational church in Waverly, Iowa.[1][2]

Missionary Career

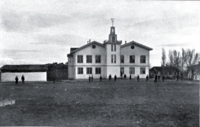

White began his missionary career in 1890. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) sent him to Merzifon in the Ottoman Empire as treasurer and dean of the Anatolia College in Merzifon.[3] Anatolia College had opened in 1887 after incorporation under Massachusetts law.[4]

White was promoted to the college's president on September 1913.[5] The College's faculty then consisted of 11 Armenians, 10 Americans, and 9 Greeks.[6] By World War I, 2,000 students had graduated from the College.[7] White stated that the "Armenians have furnished the larger part of the students hitherto and the constituency is not merely local."[8]

Background

Armenian Christians had been an oppressed (and restive) minority in the Ottoman Empire, often turning to Protestant missionaries as well as Eastern Orthodox Russia for protection. Russian troops had been stationed in several Eastern Ottoman Provinces after the treaty ending the Russo-Turkish war, pending the Ottoman Empire's adoption of reforms, even as modified by the Congress of Berlin in 1878. Armenian nationalists rioted in Constantinople and in the provinces shortly after White's arrival in Merzifon, and were brutally suppressed in the Hamidian Massacres of 1894-1896. Ottoman military officers, including Mustafa Kemel Ataturk seized power from Sultan Abdülhamid II and attempted to establish a constitutional monarchy in the Young Turk Revolution of 1908.

The collapsing Ottoman Empire lost its Balkan possessions after Orthodox Christian uprisings in the First Balkan War of 1912–13. As White's college presidency began, at least half a million Muslim Ottomans from the Empire's former Balkan possessions sought refuge in Turkey,[9] some seeking revenge against Christians.[10] Muslim Balkan refugees intensified Turkish fears that the Empire's Armenian Christian minority—with the assistance or encouragement of Western governments—might also attempt to establish an independent state and thus break up the Empire's Eastern provinces.[11][12]

Armenian Genocide

White considered the demographic situation as an "internal breach that would come to surface as a deadly wound."[13] He predicted that since many Christians lived in the area, conflict would be inevitable, merely awaiting an opportune time and conditions.[13]

When the Turkish government began deporting Armenians in 1915, White remained in Merzifon (which Armernians called Marsovan). At the time, half the city's 30,000 people were Armenian.[7] By spring, "the situation for Armenia, became excessively acute", White stated "the Turks determined to eliminate the Armenian question by eliminating the Armenians."[1] White found "the misery, the agony, the suffering (of the deportees) beyond power of words to express, almost beyond the power of hearts to conceive. In bereavement, thirst, hunger, loneliness, hopelessness, the groups were swept on and on along roads which had no destination."[1] White, estimated 11,500 deportees, or almost half Merzifon's population.[14] White also estimated that 1,200 Armenians converted to Islam to evade deportations and save their lives.[14] [15][16]

On August 19, Turkish authorities visited the Anatolian colleges and demanded deportation of all Armenian students and teachers.[7] White "refused to tell" where Armenians were hiding so as to save them from getting deported or killed.[1] However, the officials threatened to execute the College staff if the Armenians weren't handed over.[1] White then agreed to hand the Armenians over and then held a prayer service for the deportees sent with the Turkish officials. The Armenian males were then separated from the women and shot outside of the city.[7] The women were deported to the Syrian desert, and none ever returned.[7] White later remarked, "thousands of women and children were swept away. Where? Nowhere. No destination was stated or intended. Why? Simply because they were Armenians and Christians and were in the hands of the Turks."[1]

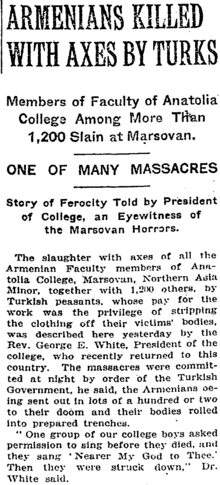

White later described the events in a New York Times article:

On the pretext of searching for deserting soldiers, concealing bombs, weapons, seditious literature or revolutionists, the Turkish officers arrested about 1,200 Armenian men at Marsovan, accompanying their investigations by horrible brutalities. There was no revolutionary activity in our region whatever. The men were sent out in lots of one or two hundred in night 'deportations' to the mountains, where trenches had been prepared. Coarse peasants, who were employed to do what was done, said it was a 'pity to waste bullets,' and they used axes.[1]

In the same article, he claimed that girls were sold in the market for "$2 to $4 each."[1] White claimed he had personally ransomed "three girls at the price of $4.40".[1]

White also provided a detailed account of the confiscated Armenian properties during the upheaval:

All the properties of the Armenians were confiscated, nominally to the state for the war fund. In this way all the Armenian houses, stores, shops, fields, gardens, vineyards, merchandise, household goods, rugs, were taken. The work was the charge of a commission, the members of which I met personally a number of times. It was commonly said that the commission did not actually receive enough for the government purposes to cover its expenses. Real estate was put up for rent at auction and was most of it bid in at prices ridiculously low by persons who were on the inside. This I know not only as a matter of common information but directly from a Turkish attorney who was in our employ and who provided himself with one of the best Armenian houses. Turks moved out of their more squalid habitations into the better Armenian houses whose owners had been 'deported.' All the property of the Armenians except some remnants left to the Armenians who had embraced Mohammedanism was thus plundered.[17][18]

Afterward, White headed a 250 person expedition funded by the Near East Relief Fund to aid Armenian refugees.[19] White also supported an independent Armenia because he believed that without a free Armenia, Armenians would have "no real security for the life of a man, the honor of a woman, the welfare of a child, the prosperity of a citizen or the rights of a father."[20] In 16 May 1916, Turkish authorities closed the college, displacing White and the remaining staff in order to establish a military hospital.[21][19] The staff of the College was eventually transported to Constantinople. The College remained a military hospital for the next two years.[21]

Return to Merzifon

George E. White returned to the Ottoman Empire and the College's presidency, reopening in 1919.[22] However, many Armenian teachers and staff had been killed, and the buildings damaged and deteriorated during the military occupation.[22] Nonetheless, White immediately began providing relief to victims of the Genocide.[22] He described the relief efforts and the College:

Inquiries are already being made by all races as to when our College will open. For the present we must press the relief work, but by fall we hope to take up also the school work. We shall need several first-class American tutors. You will remember that eight of our Armenian teachers were killed by the Turks. Everywhere girls are coming back who were carried away and forcibly married to Turks. Two of our Marsovan schoolgirls were taken into the homes of Turks in Marsovan. They ran away together and got to Constantinople in some way. I saw in one orphanage of this sort a few days ago thirty girls. They expect to have seventy-five. They have sad stories to tell. Most of those who had had babies have left them in the Turkish homes. I heard of one of our Marsovan girls, married to an Arab, who might come back now; but her face had been tattooed in such a way that she was ashamed to show it among people who had known her. The poor mistreated girls! How shall we bring new hope, new life, to them?[23]

White helped establish various additions to the campus which included an agriculture section.[22] By 1919, an orphanage was established within the premises of the school which sheltered as many as 2,000 Armenian orphans.[8] In addition, a "baby house" was established to house Armenian girls and babies displaced by the Genocide.[7]

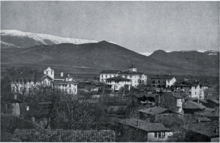

However, the Turkish government in 1921 ordered the Anatolian College in Merzifon closed. The College ultimately relocated to Salonika, Greece.[6] In 1924, George White was appointed president of the as-yet-unconstructed Salonika branch. He later described that upon his arrival, the building was "without a book, a bell or a bench." White raised funds to construct and operate the new College.[2]

Later life

After a total of forty-three years of missionary service, White retired in 1934 and returned to the United States.[2]

On 27 April 1946, George E. White died in his home, 287 4th Avenue, Claremont, California at the age of 84.[2] His body was transferred to Iowa where he was buried with his parents (and later with his children) at Hazelwood Cemetery in Grinnell.[24]

See also

- American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

- Witnesses and testimonies of the Armenian Genocide

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 "Armenians Killed with Axes by Turks". New York Times Current History Edition: "The European War" 13. 1917.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "Dr. White, Headed College in Greece". New York Times. 4 May 1946. p. 15.

- ↑ Grabill 1971, p. 26.

- ↑ Shaw, Albert (1921). "The College Closed by Kemal". The American Review of Reviews 64: 318.

- ↑ Frank Andrews Stone 2004, p. 219.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Tejirian, Eleanor H.; Simon, Reeva Spector. Conflict, conquest, and conversion : two thousand years of Christian missions in the Middle East. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0231138644.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Shenk 2012, p. 37.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 White, George E. (February 1919). "A Sacred Trust". The New Armenia (New Armenia Publishing Company) 11 (2): 20–21.

- ↑ Kévorkian, Raymond H. (2011). The Armenian genocide: a complete history(Reprinted. ed.). (London: I. B. Tauris, 2011), p. 141. ISBN 1-84885-561-3

- ↑ Kévorkian 2011, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ Lieberman, Benjamin. The Holocaust and Genocides in Europe. (A&C Black, 2013). pp. 51–56. ISBN 9781441194787

- ↑ Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' Crime Against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2012). pp. xv–xix. ISBN 9780691153339.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Kieser 2010, p. 178.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Bartov 2001, p. 211.

- ↑ Akçam 2007, p. 293.

- ↑ Morley 2000, p. x.

- ↑ Sarafian 1998, p. 82.

- ↑ Der Matossian, Bedross (6 October 2011). "The Taboo within the Taboo: The Fate of 'Armenian Capital' at the End of the Ottoman Empire". European Journal of Turkish Studies. ISSN 1773-0546.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "NEAR EAST RELIEF EXPEDITION LEAVES". New York Times. February 17, 1919.

- ↑ Winter 2003, p. 262.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Frank Andrews Stone 2004, p. 220.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Peterson 2004, p. 63.

- ↑ Francis Rufus Bellamy (September 1919). "News from Marsovan, Turkey". The Outlook 123: 33.

- ↑ http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=92409634

Bibliography

- Akçam, Taner (2007). A Shameful Act: : The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-8665-2.

- Grabill, Joseph L. (1971). Protestant Diplomacy and the Near East: Missionary Influence on American Policy, 1810-1927. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 1452911312.

- Peterson, Merrill D. (2004). "Starving Armenians" : America and the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1930 and after (1. publ. ed.). Charlottesville [u.a.]: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0813922674.

- Sarafian, Ara (1998). James L. Barton, ed. "Turkish atrocities": statements of American missionaries on the destruction of Christian communities in Ottoman Turkey, 1915–1917. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Gomidas Institute. ISBN 1-884630-04-9.

- Shenk, Robert (2012). America's Black Sea fleet the U.S. Navy amidst war and revolution, 1919-1923. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1612513026.

- Kévorkian, Raymond H. (2011). The Armenian genocide: a complete history (Reprinted. ed.). London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84885-561-3.

- Morley, Bertha B. (2000). Hilmar Kaiser, ed. Marsovan 1915: the diaries of Bertha B. Morley (2. ed ed.). Ann Arbor, Mich.: Gomidas Inst.[u.a.] ISBN 0953519139.

- Bartov, Omer; Mack, Phyllis (2001). In God's name: genocide and religion in the twentieth century. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 1571812148.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2010). Nearest East American millennialism and mission to the Middle East. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-4399-0224-0.

- Frank Andrews Stone (2004). Richard G. Hovannisian, ed. Armenian Sebastia/Sivas and Lesser Armenia. Costa Mesa, Calif.: Mazda Publ. ISBN 1568591527.

- Winter, J. M. (2003). America and the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-16382-1.