Geological history of oxygen

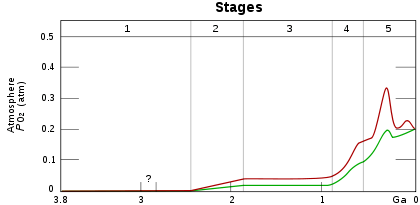

Stage 1 (3.85–2.45 Ga): Practically no O2 in the atmosphere.

Stage 2 (2.45–1.85 Ga): O2 produced, but absorbed in oceans & seabed rock.

Stage 3 (1.85–0.85 Ga): O2 starts to gas out of the oceans, but is absorbed by land surfaces and formation of ozone layer.

Stages 4 & 5 (0.85 Ga–present): O2 sinks filled, the gas accumulates.[1]

Before photosynthesis evolved, Earth's atmosphere had no free oxygen (O2).[2] Oxygen was first produced by photosynthetic prokaryotic organisms that emitted O2 as a waste product. These organisms lived long before the first build-up of oxygen in the atmosphere,[3] perhaps as early as 3.5 billion years ago. The oxygen they produced would have almost instantly been removed from the atmosphere by weathering of reduced minerals, most notably iron. This 'mass rusting' led to the deposition of banded iron formations. Oxygen only began to persist in the atmosphere in small quantities about 50 million years before the start of the Great Oxygenation Event.[4] This mass oxygenation of the atmosphere resulted in rapid buildup of free oxygen. At current atmospheric rates, today's concentration of oxygen could be produced by photosynthesisers in 2,000 years.[5] Of course, in the absence of plants, photosynthesis was slower in the Precambrian, and the levels of O2 attained were modest (less than 10% of today's) and probably fluctuated greatly; oxygen may even have disappeared from the atmosphere again around 1,900 million years ago[6] These fluctuations in oxygen had little direct effect on life, with mass extinctions not observed until the appearance of complex life around the start of the Cambrian period, 541 million years ago.[7] The presence of O

2 provided life with new opportunities. Aerobic metabolism is more efficient than anaerobic pathways, and the presence of oxygen undoubtedly created new possibilities for life to explore.[8]:214, 586[9]

Since the start of the Cambrian period, atmospheric oxygen concentrations have fluctuated between 15% and a maximum of 35% of atmospheric volume[10] towards the end of the Carboniferous period (about 300 million years ago), a peak which may have contributed to the large size of insects and amphibians at that time.[9] Whilst human activities, such as the burning of fossil fuels, have an impact on relative carbon dioxide concentrations, their impact on the much larger concentration of oxygen is less significant.[11]

Effects on life

The concentration of atmospheric oxygen is often cited as a possible contributor to large-scale evolutionary phenomena, such as the origin of the multicellular Ediacara biota, the Cambrian explosion, trends in animal body size, and other extinction and diversification events.[9]

The large size of insects and amphibians in the Carboniferous period, where oxygen reached 35% of the atmosphere, has been attributed to the limiting role of diffusion in these organisms' metabolism. But Haldane's essay[12] points out that it would only apply to insects. However, the biological basis for this correlation is not firm, and many lines of evidence show that oxygen concentration is not size-limiting in modern insects.[9] Interestingly, there is no significant correlation between atmospheric oxygen and maximum body size elsewhere in the geological record.[9] Ecological constraints can better explain the diminutive size of post-Carboniferous dragonflies - for instance, the appearance of flying competitors such as pterosaurs and birds and bats.[9]

Rising oxygen concentrations have been cited as a driver for evolutionary diversification, although the physiological arguments behind such arguments are questionable, and a consistent pattern between oxygen levels and the rate of evolution is not clearly evident.[9] The most celebrated link between oxygen and evolution occurs at the end of the last of the Snowball glaciations, where complex multicellular life is first found in the fossil record. Under low oxygen levels, regular 'nitrogen crises' could render the ocean inhospitable to life.[9] Significant concentrations of oxygen were just one of the prerequisites for the evolution of complex life.[9] Models based on uniformitarian principles (i.e. extrapolating present-day ocean dynamics into deep time) suggest that such a level was only reached immediately before metazoa first appeared in the fossil record.[9] Further, anoxic or otherwise chemically 'nasty' oceanic conditions that resemble those supposed to inhibit macroscopic life re-occur at intervals through the early Cambrian, and also in the late Cretaceous – with no apparent impact on lifeforms at these times.[9] This might suggest that the geochemical signatures found in ocean sediments reflect the atmosphere in a different way before the Cambrian - perhaps as a result of the fundamentally different mode of nutrient cycling in the absence of planktivory.[7][9]

References

- ↑ http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/361/1470/903.full.pdf

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (3 October 2013). "Earth’s Oxygen: A Mystery Easy to Take for Granted". New York Times. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ↑ Dutkiewicz, A.; Volk, H.; George, S. C.; Ridley, J.; Buick, R. (2006). "Biomarkers from Huronian oil-bearing fluid inclusions: an uncontaminated record of life before the Great Oxidation Event". Geology 34 (6): 437. Bibcode:2006Geo....34..437D. doi:10.1130/G22360.1.

- ↑ Anbar, A.; Duan, Y.; Lyons, T.; Arnold, G.; Kendall, B.; Creaser, R.; Kaufman, A.; Gordon, G.; Scott, C.; Garvin, J.; Buick, R. (2007). "A whiff of oxygen before the great oxidation event?". Science 317 (5846): 1903–1906. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1903A. doi:10.1126/science.1140325. PMID 17901330.

- ↑ Dole, M. (1965). "The Natural History of Oxygen". The Journal of General Physiology 49 (1): Suppl:Supp5–27. doi:10.1085/jgp.49.1.5. PMC 2195461. PMID 5859927.

- ↑ Frei, R.; Gaucher, C.; Poulton, S. W.; Canfield, D. E. (2009). "Fluctuations in Precambrian atmospheric oxygenation recorded by chromium isotopes". Nature 461 (7261): 250–253. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..250F. doi:10.1038/nature08266. PMID 19741707. Lay summary.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Butterfield, N. J. (2007). "Macroevolution and macroecology through deep time". Palaeontology 50 (1): 41–55. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00613.x.

- ↑ Freeman, Scott (2005). Biological Science, 2nd. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson – Prentice Hall. pp. 214, 586. ISBN 0-13-140941-7.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 9.10 9.11 Butterfield, N. J. (2009). "Oxygen, animals and oceanic ventilation: An alternative view". Geobiology 7 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1472-4669.2009.00188.x. PMID 19200141.

- ↑ Berner, R. A. (Sep 1999). "Atmospheric oxygen over Phanerozoic time" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96 (20): 10955–10957. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9610955B. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.20.10955. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 34224. PMID 10500106.

- ↑ Emsley, John (2001). "Oxygen". Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 297–304. ISBN 0-19-850340-7.

- ↑ J.B.S. Haldane in "On Being the Right Size" paragraph 7

External links

- First breath: Earth's billion-year struggle for oxygen New Scientist, #2746, 5 February 2010 by Nick Lane.

- The Mystery of Earth's Oxygen New York Times, 3 October 2013 by Carl Zimmer.