Geography of New York

The geography of New York State varies widely. While the state is best known for New York City's urban atmosphere, especially Manhattan's skyscrapers, most of the state is dominated by farms, forests, rivers, mountains, and lakes. New York's Adirondack Park is larger than any U.S. National Park in the contiguous United States.[1] Niagara Falls, on the Niagara River as it flows from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario, is a popular attraction. The Hudson River begins near Lake Tear of the Clouds and flows south through the eastern part of the state without draining lakes George or Champlain. Lake George empties at its north end into Lake Champlain, whose northern end extends into Canada, where it drains into the Richelieu River and then the St. Lawrence. Four of New York City's five boroughs are on the three islands at the mouth of the Hudson River: Manhattan Island, Staten Island, and Brooklyn and Queens on Long Island.

"Upstate" is a common term for New York counties north of suburban Westchester, Rockland and Dutchess counties. Upstate New York typically includes Lake George and Oneida Lake in the northeast; and rivers such as the Delaware, Genesee, Mohawk, and Susquehanna. The highest elevation in New York is Mount Marcy in the Adirondacks.

Location and size

New York is located in the northeastern United States, in the Mid-Atlantic Census Bureau division. New York covers an area of 54,556 square miles (141,299 km²) and ranks as the 27th largest state by size.[2] The state borders six U.S. states: Pennsylvania and New Jersey to the south, and Connecticut, Rhode Island (across Long Island Sound), Massachusetts, and Vermont to the east. New York also borders the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec to the north. Additionally, New York touches the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and two of the Great Lakes: Lake Erie to the west and Lake Ontario to the northwest.

Topography

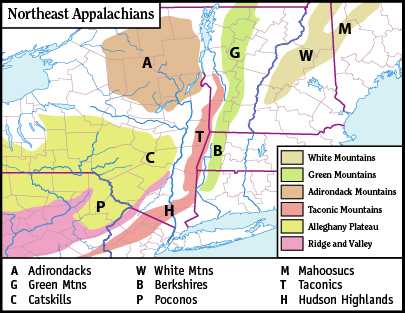

New York lies upon the portion of the Appalachian Mountains where the mountains generally assume the character of hills and finally sink to a level of the lowlands that surround the great depression filled by Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River. Three distinct mountain masses can be identified in the state. The most easterly of these ranges—a continuation of the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia—enters the state from New Jersey and extends northeast through Rockland and Orange counties to the Hudson River, continuing on the east side of that river as the highlands of Putnam and Dutchess counties. A northerly extension of the same range passes into the Green Mountains of western Massachusetts and Vermont. This range is known in New York as the Hudson Highlands. The highest peaks are 1,000 to 1,700 feet (300 to 520 m) above sea level. The rocks that compose these mountains are principally primitive or igneous, and the mountains themselves are rough, rocky, precipitous, and unfit for cultivation.[3]

The second series of mountains enters the state from Pennsylvania and extends northeast through Sullivan, Ulster, and Greene counties, terminating and culminating in the Catskill Mountains west of the Hudson. The highest peaks are 3,000 to 3,800 feet (910 to 1,160 m) above sea level. The Shawangunk Mountains, a high and continuous ridge extending between Sullivan and Orange counties and into the southern part of Ulster County, is the extreme eastern range of this series. The Helderberg and Hellibark Mountains are spurs extending north from the main range into Albany and Schoharie counties. This whole mountain system is principally composed of rocks of the New York system above the Medina sandstone. The summits are generally crowned with red sandstone and with the conglomerate of the coal measures. The declivities are steep and rocky, and a large share of the surface is too rough for cultivation.[3]

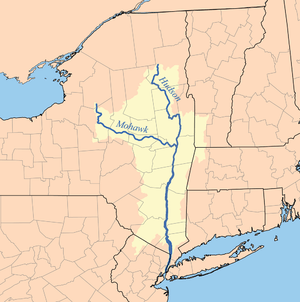

The third mountainous region, occupying the northeast part of the state, is known as the Adirondack Mountains. The region is bounded to the south by the Mohawk River, south of which the highlands become part of the Allegheny Plateau, in the form of broad, irregular hills, broken by the deep ravines of streams. The valley of the Mohawk separates the Allegheny Plateau to the south from the highlands leading to the Adirondacks to the north, reaching its narrowest point in the neighborhood of Little Falls, the Noses, and other places. North of the Mohawk the highlands extend northeast in several distinct ranges, all terminating upon Lake Champlain. The culminating point of the whole system, and the highest mountain in the state, is Mount Marcy, standing 5,467 feet (1,666 m) above sea level. The rocks of all this region are principally of igneous origin, and the mountains are usually wild, rugged, and rocky. A large share of the surface is entirely unfit for cultivation, but the region is rich in minerals, and especially in an excellent variety of iron ore.

In western New York, a series of hills forming spurs of the Allegheny Mountains enter the state from Pennsylvania and occupy the entire southern half of the west part of the state. An irregular line extending through the southerly counties forms the watershed that separates the northern and southern drainage; and from it the surface gradually declines northward until it finally terminates in the level of Lake Ontario. The portion of the state lying south of this watershed and occupying the greater part of the two southerly tiers of counties is entirely occupied by these hills. Along the Pennsylvania line they are usually abrupt and are separated by narrow ravines, but toward the north their summits become broader and less broken. A considerable portion of the highland region is too steep for profitable cultivation and is best adapted to grazing. The highest summits in Allegany and Cattaraugus counties are 2,000 to 2,500 feet (610 to 760 m) above sea level.[3]

From the summits of the watershed, the highlands usually descend toward Lake Ontario in a series of terraces, the edges of which are outcrops of different rocks beneath the surface. These terraces are usually smooth, and, although inclined toward the north, the inclination is generally so slight that they appear level. Between the hills of the south and the level land of the north is a beautiful rolling region, the ridges gradually declining toward the north. In that part of the state, south of the most eastern mountain range, the surface is generally level or broken by low hills. In Manhattan and Westchester County, these hills are principally composed of primitive rocks. The surface of Long Island is generally level or gently undulating. A ridge 150 to 200 feet (46 to 61 m) high, composed of sand, gravel, and clay, extends east and west across the island north of its center.[3]

Rivers and Lakes

The river system of the state has two general divisions. The first is the streams tributary to the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River. The second are those tributaries that flow in a general southerly direction. The watershed divide that separates these two systems extends in an irregular line eastward from Lake Erie, through the southern tier of counties to near the northeast corner of Chemung County. It then turns northeast to the Adirondack Mountains in Essex County, then southeast to the east extremity of Lake George, and then nearly due east to the east border of the state.[3]

The northerly division has five general subdivisions. The most westerly of these comprises all the streams flowing into Lake Erie and the Niagara River and those flowing into Lake Ontario west of the Genesee River. In Chautauqua County, the streams are short and rapid, as the watershed approaches within a few miles of Lake Erie. Cattaraugus, Buffalo, Tonawanda, and Oak Orchard creeks are the most important streams in this division. Buffalo Creek is chiefly noted for forming Buffalo Harbor at its mouth; and the Tonawanda for 12 miles (19 km) from its mouth was once used for canal navigation. Oak Orchard and other creeks flowing into Lake Ontario descend from the interior in a series of rapids, affording a large amount of waterpower.[3]

Tho second subdivision comprises the Genesee River and its tributaries. The Genesee rises in the northern part of Pennsylvania and flows in a generally northerly direction to Lake Ontario. Its upper course is through a narrow valley bordered by steep, rocky hills. Upon the line of Wyoming and Livingston counties, it breaks through a mountain barrier in a deep gorge and forms the Portage Falls. Below this point the course of the river is through a valley 1 to 2 miles (1.6 to 3.2 km) wide and bordered by banks 50 to 150 feet (15 to 46 m) high. At Rochester it flows over the precipitous edges of the Niagara limestone, forming the Upper Genesee Falls; and 3 miles (4.8 km) below it flows over the edge of the Medina sandstone, forming the Lower Genesee Falls. The principal tributaries of this stream are Canaseraga, Honeoye, and Conesus creeks from the south, and Oatka and Black creeks from the west. Honeoye, Canadice, Hemlock, and Conesus lakes—four of the Finger Lakes—lie within the Genesee Basin.[3] The third subdivision includes the Oswego River and its tributaries, and the small streams flowing into Lake Ontario between the Genesee and Oswego rivers. The basin of the Oswego includes most of the inland lakes, which form a peculiar feature of the landscape in the interior of the state. The principal of these lakes are Cayuga, Seneca, Canandaigua, Skaneateles, Crooked, and Owasco lakes, all occupying long, narrow valleys, and extending from the level land in the center far into the highland region of the south (many of those lakes just mentioned are also part of the Finger Lakes). The valleys they occupy appear like immense ravines formed by some tremendous force that tore the solid rocks from their original beds, from the general level of the surrounding summits, down to the present bottoms of the lakes. Oneida and Onondaga lakes occupy level land in the northeast part of the Oswego Basin. Mud Creek, the most westerly branch of the Oswego River, takes its rise in Ontario County, flows northeast into Wayne County, where it unites with Canandaigua Outlet and takes the name of Clyde River; then it flows east to the west line of Cayuga County, where it empties into the Seneca River. This latter stream, made up of the outlets of Seneca and Cayuga Lakes, from this point flows in a northeasterly course, and receives successively the outlets of Owasco, Skaneateles, Onondaga, and Oneida lakes. From the mouth of the last-named stream it takes the name Oswego River, and its course is nearly due north to Lake Ontario.[3]

The fourth subdivision includes the streams flowing into Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River east of the mouth of the Oswego. The principal of these are the Salmon, Black, Oswegatchie, Grasse, and Raquette rivers. The water is usually very dark, being colored with iron and the vegetation of swamps.[3]

The fifth subdivision includes all the streams flowing into Lakes George and Champlain. They are mostly mountain torrents, frequently interrupted by cascades. The principal streams are the Chazy, Saranac, and Ausable rivers, and Wood Creek. Deep strata of Tertiary clay extend along the shores of Lake Champlain and Wood Creek. The water of most of the streams in this region is colored by the iron over which it flows.

The second general division of the river system of the state includes the basins of the Allegheny, Susquehanna, Delaware, and Hudson. The Allegheny Basin embraces the southerly half of Chautauqua and Cattaraugus counties and the southwest corner of Allegany County. The Allegheny River enters the state from the south in the southeast corner of Cattaraugus County, flows in nearly a semicircle, with its outward curve toward the north, and flows out of the state in the southwest part of the same county. It receives several tributaries from the north and east. These streams mostly flow in deep ravines bordered by steep, rocky hillsides. The watershed between this basin and Lake Erie approaches within a few miles of the lake, and is elevated 800 to 1,000 feet (240 to 300 m) above it.[3]

The Susquehanna Basin occupies about one-third of the south border of the state. The river takes its rise in Otsego Lake, and, flowing southwest to the Pennsylvania line, receives Charlotte River from the south and the Unadilla River from the north. After a course of a few miles in Pennsylvania, it again enters New York and flows in a general westerly direction to near the western border of Tioga County, whence it turns south and again enters Pennsylvania. Its principal tributary from the north is the Chenango River. The Tioga River enters New York from Pennsylvania near the eastern border of Steuben County, flows north, receives the Canisteo River from the west and the Cohocton River from the north. From the mouth of the latter, the stream takes the name Chemung River, and flows in a southeast direction, into the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania, a few miles south of the state line. The upper course of these streams is generally through deep ravines bordered by steep hillsides, but below they are bordered by wide intervales.[3]

The Delaware Basin occupies Delaware and Sullivan counties and portions of several of the adjacent counties. The north or principal branch of the river rises in the northeast part of Delaware County and flows southwest to near the Pennsylvania line; then it turns southwest and forms the boundary of the state to the line of New Jersey. Its principal branches are the Pepacton and Neversink rivers. These streams all flow in deep, narrow ravines bordered by steep, rocky hills.[3]

The basin of the Hudson occupies about two-thirds of the east border of the state, and a large territory extending into the interior. The remote sources of the Hudson are among the highest peaks of the Adirondacks, more than 4,000 feet (1,200 m) above sea level. Several of the little lakes that form reservoirs of the Upper Hudson are 2,500 to 3,000 feet (760 to 910 m) above sea level. The stream rapidly descends through the narrow defiles into Warren County, where it receives from the east the outlet of Schroon Lake, and the Sacandaga River from the west. Below the mouth of the latter the river turns eastward, and breaks through the barrier of the Luzerne Mountains in a series of rapids and falls. At Fort Edward it again turns south and flows with a rapid current, frequently interrupted by falls, to Troy, 160 miles (260 km) from the ocean. At this place the river falls into an estuary, where its current is affected by the tide; and from this place to its mouth it is a broad, deep, sluggish stream. About 60 miles (97 km) from its mouth the Hudson breaks through the rocky barrier of the highlands, forming the most easterly of the Appalachian Mountain ranges; and along its lower course it is bordered on the west by a nearly perpendicular wall of basaltic rock 300 to 500 feet (91 to 152 m) high, known as The Palisades. Above Troy, the Hudson receives the Hoosic River from the east and the Mohawk River from the west. The former stream rises in western Massachusetts and Vermont, and the latter near the center of New York.[3]

At Little Falls and The Noses, the Mohawk breaks through mountain barriers in a deep, rocky ravine; and at Cohoes, about 1 mile (1.6 km) from its mouth, it flows down a perpendicular precipice of 70 feet (21 m). Below Troy the tributaries of the Hudson are all comparatively small streams. South of the highlands the river spreads out into a wide expanse known as Haverstraw Bay. A few small streams upon the extreme eastern border of the state flow eastward into the Housatonic River, and several small branches of the Passaic River rise in the southern part of Rockland County.[3]

Lake Erie forms a portion of the western boundary of the state. It is 240 miles (390 km) long, with an average width of 38 miles (61 km), and it lies mostly west of the bounds of the state. It is 334 feet (102 m) above Lake Ontario, 565 feet (172 m) above sea level, and has an average depth of 120 feet (37 m). The greatest depth ever obtained by soundings is 270 feet (82 m). The harbors upon the lake are Buffalo, Silver Creek, Dunkirk, and Barcelona.[3]

The Niagara River, forming the outlet of Lake Erie, is 34 miles (55 km) long, and, on average, more than a mile wide. About 20 miles (32 km) below Lake Erie the rapids commence; and 2 miles (3.2 km) further below are Niagara Falls. For 7 miles (11 km) below the falls the river has a rapid course between perpendicular, rocky banks, 200 to 300 feet (61 to 91 m) high, but below it emerges from the highlands and flows 7 miles (11 km) to Lake Ontario in a broad, deep, and majestic current.[3]

Lake Ontario forms a part of the northern boundary to the western half of the state. Its greatest length is 130 miles (210 km) and its greatest width is 55 miles (89 km). It is 232 feet (71 m) above sea level, and its greatest depth is 600 feet (180 m). Its principal harbors on the American shore are Lewiston, Youngstown, Port Genesee, Sodus and Little Sodus bays, Oswego, Sackets Harbor, and Cape Vincent. The St. Lawrence River forms the outlet of the lake and the northern boundary of the state to the east line of St. Lawrence County. It is a broad, deep river, flowing with a strong yet sluggish current until it passes the limits of this state. In the upper part of its course it encloses a great number of small islands, known as the Thousand Islands.[3]

The surfaces of the Great Lakes are subject to variations of level, probably due to prevailing winds, unequal amounts of rain, and evaporation. The greatest difference known in Lake Erie is 7 feet (2.1 m), and in Lake Ontario 4 feet (1.2 m). The time of these variations is irregular, and the interval between the extremes often extends through several years. A sudden rise and fall of several feet has been noticed upon Lake Ontario at rare intervals, produced by some unknown cause.[3]

State parks

New York has many state parks and two major forest preserves. The Adirondack Park, roughly the size of the state of Vermont and the largest state park in the United States, was established in 1892 and given state constitutional protection in 1894.[1] The thinking that led to the creation of the park first appeared in George Perkins Marsh's Man and Nature, published in 1864. Marsh argued that deforestation could lead to desertification; referring to the clearing of once-lush lands surrounding the Mediterranean, he asserted "the operation of causes set in action by man has brought the face of the earth to a desolation almost as complete as that of the moon."[4]

The Catskill Park was protected in legislation passed in 1885, which declared that its land was to be conserved and never put up for sale or lease. Consisting of 700,000 acres (2,800 km2) of land, the park is a habitat for bobcats, minks and fishers. There are some 400 black bears living in the region. The state operates numerous campgrounds, and there are over 300 miles (480 km) of multi-use trails in the park.

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "The Adirondack Park". NYS Adirondack Park Agency. 2003. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- ↑ "Land and Water Area of States (2000)". www.infoplease.com. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 French, John Homer. Historical and statistical gazetteer of New York State. Syracuse, New York: R. Pearsall Smith; 1860. OCLC 224691273. p. 19–23.

- ↑

| ||||||||||||||||||