Geography of China

China stretches some 5,026 kilometers across the East Asian landmass. China is bordered in the east by the East China Sea, Korea Bay, Yellow Sea, Taiwan Strait, and South China Sea, and shares land borders with a total of 14 countries in the north, south and west.

China has been officially and conveniently divided into 5 homogeneous physical macro-regions: Eastern China (subdivided into the Northeast plain, North plain, and southern hills), Xinjiang-Mongolia, and the Tibetan highlands.

It has great physical diversity. The east and south of the country consists of fertile lowlands and foothills, and is the location of most of China's agricultural output and human population. The west and north of the country is dominated by sunken basins (such as the Gobi and the Taklamakan), rolling plateaus, and towering massifs. It contains part of the highest tableland on earth, the Tibetan Plateau, and has much lower agricultural potential population.

Traditionally, the Chinese population centered on the Chinese central plain and oriented itself toward its own enormous inland market, developing as an imperial power whose center lay in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River on the northern plains. More recently, the 18,000 km coastline has been used extensively for export-oriented trade, causing the coastal provinces to become the leading economic center.

With an area of about 9.6 million km², the People's Republic of China is the 3rd largest country in total area behind Russia and Canada, and very similar in size to the United States. The exact land area is sometimes challenged by border disputes, most notably about Taiwan, Aksai Chin, the Trans-Karakoram Tract, and South Tibet.[1]

Physical geography

Topography

Generalities

The topography of China has been divided by the government into five homogeneous physical macro-regions, namely Eastern China (subdivided into the northeast plain, north plain, and southern hills), Xinjiang-Mongolia, and the Tibetan highlands[2] It is diverse with snow-capped mountains, deep river valleys, broad basins, high plateaus, rolling plains, terraced hills, sandy dunes, craggy karsts, volcanic calderas, low-latitude glaciers and other landforms present in myriad variations. In general, the land is high in the west and descends to the east coast. Mountains (33 percent), plateaus (26 percent) and hills (10 percent) account for nearly 70 percent of the country's land surface. Most of the country's arable land and population are based in lowland plains (12 percent) and basins (19 percent), though some of the greatest basins are filled with deserts. The country's rugged terrain presents problems for the construction of overland transportation infrastructure and requires extensive terracing to sustain agriculture, but is conducive to the development of forestry, mineral and hydropower resources, and tourism.

Eastern China

- Northeast plain

Northeast of Shanhaiguan, a narrow sliver of flat coastal land opens up into the vast Manchurian Plain. The plains extend north to the crown of the "Chinese rooster," near where the Greater and Lesser Hinggan ranges converge. The Changbai Mountains to the east divide China from the Korean peninsula. Compared with the rest of the area of China, here live the most Chinese people due to its adequate climate and topography.

- North plain

The Taihang Mountains form the western side of the triangular North China Plain. The other two sides are the Pacific coast to the east and the Yangtze River to the southwest. The vertices of this triangle are Beijing to the north, Shanghai to the southeast, and Yichang to the southwest. This alluvial plain, fed by the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, is one of the most heavily populated regions of China. The only mountains in the plain are the Taishan in Shandong and Dabie Mountains of Anhui.

Beijing, situated at the north tip of the North China Plain, is shielded by the intersection of the Taihang and Yan Mountains. Further north are the drier grasslands of the Inner Mongolian Plateau, traditionally home to pastoralists. To the south are agricultural regions, traditionally home to sedentary populations. The Great Wall of China was built in the mountains across the mountains that mark the southern edge of the Inner Mongolian Plateau. The Ming-era walls run over 2,000 km east to west from Shanhaiguan on the Bohai coast to the Hexi Corridor in Gansu.

- South (hills)

East of the Tibetan Plateau, deeply folded mountains fan out toward the Sichuan Basin, which is ringed by mountains with 1,000-3,000 m elevation. The floor of the basin has an average elevation of 500 m and is home to one of the most densely farmed and populated regions of China. The Sichuan Basin is capped in the north by the eastward continuation of the Kunlun range, the Qinling, and the Dabashan. The Qinling and Dabashan ranges form a major north-south divide across China Proper, the traditional core area of China. Southeast of the Tibetan Plateau and south of the Sichuan Basin is the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, which occupies much of southwest China. This plateau, with an average elevation of 2,000 m, is known for its limestone karst landscape.

South of the Yangtze, the landscape is more rugged. Like Shanxi Province to the north, Hunan and Jiangxi each have a provincial core in a river basin that is surrounded by mountains. The Wuling range separates Guizhou from Hunan. The Luoxiao and Jinggang divide Hunan from Jiangxi, which is separated from Fujian by the Wuyi Mountains. The southeast coastal provinces, Zhejiang, Fujian and Guangdong, have rugged coasts, with pockets of lowland and mountainous interior. The Nanling, an east-west mountain range across northern Guangdong, seals off Hunan and Jiangxi from Guangdong.

Xinjiang-Mongolia

Northwest of the Tibetan Plateau, between the northern slope of Kunlun and southern slope of Tian Shan, is the vast Tarim Basin of Xinjiang, which contains the Taklamakan Desert. The Tarim Basin, the largest in China, measures 1,500 km from east to west and 600 km from north to south at its widest parts. Average elevation in the basin is 1,000 m. To the east, the basin descends into the Hami-Turpan Depression of eastern Xinjiang, where the dried lake bed of Lake Ayding, at −154m below sea level, is the lowest surface point in China and the third-lowest in the world. With temperatures that have reached 49.6 C., the lake bed ranks as one of the hottest places in China. North of Tian Shan is Xinjiang's second great basin, the Junggar, which contains the Gurbantünggüt Desert. The Junggar Basin is enclosed to the north by the Altay Mountains, which separate Xinjiang from Russia and Mongolia.

Northeast of the Tibetan Plateau, the Altun Shan-Qilian Mountains range branches off the Kunlun and creates a parallel mountain range running east-west. In between in northern Qinghai is the Qaidam Basin, with elevations of 2,600–3,000 m and numerous brackish and salt lakes. North of the Qilian is Hexi Corridor of Gansu, a natural passage between Xinjiang and China Proper that was part of the ancient Silk Road and traversed by modern highway and rail lines to Xinjiang. Further north, the Inner Mongolian Plateau, between 900–1,500 m in elevation, arcs north up the spine of China and becomes the Greater Hinggan Range of Northeast China.

Between the Qinling and the Inner Mongolian Plateau is Loess Plateau, the largest of its kind in the world, covering 650,000 km² in Shaanxi, parts of Gansu and Shanxi provinces, and some of Ningxia-Hui Autonomous Region. The plateau is 1,000–1,500m in elevation and is filled with loess, a yellowish, loose soil that travels easily in the wind. Eroded loess silt gives the Yellow River its color and name. The Loess Plateau is bound to the east by the Luliang Mountain of Shanxi, which has a narrow basin running north to south along the Fen River. Further east are the Taihang Mountains of Hebei, the dominant topographical feature of North China.

Tibetan highlands

- Highlands

The world's tallest mountains, the Himalayas, Karakorum, Pamirs and Tian Shan divide China from South and Central Asia.[3] Eleven of the 17 tallest mountain peaks are located on China's western borders. They include world's tallest peak Mt. Everest (8848m) in the Himalayas on the border with Nepal and the world's second tallest peak, K2 (8611m) on the border with Pakistan. From these towering heights in the west, the land descends in steps like a terrace.

North of the Himalayas and east of the Karakorum/Pamirs is the vast Tibetan Plateau, the largest and highest plateau in the world, also known as the "Roof of the World." The plateau has an average elevation of 4,000m above sea level and covers an area of 2.5 million square kilometers, or about one-fifth of China's land mass. In the north, the plateau is hemmed in by the Kunlun Mountains, which extends eastward from the intersection of the Pamirs, Karakorum and Tian Shan.

- Tallest mountain peaks

Besides Mt. Everest and K2, the other 9 of the world's 17 tallest peaks on China's western borders are: Lhotse (8516m, 4th highest), Makalu (8485m, 5th), Cho Oyu (8188m, 6th), Gyachung Kang (7952m, 15th) of the Himalayas on the border with Nepal and Gasherbrum I (8080m, 11th), Broad Peak (8051m, 12th), Gasherbrum II (8035m, 13th), Gasherbrum III (7946m, 16th) and Gasherbrum IV (7932m, 17th) of the Karakorum on the border with Pakistan. The tallest peak entirely within China is Shishapangma (8013m, 14th) of the Tibetan Himalayas in Nyalam County of Tibet Autonomous Region. In all, 9 of the 14 mountain peaks in the world over 8,000m are in or on the border of China. Another notable Himalayan peak in China is Namchabarwa (7782m, 28th), near the great bend of the Yarlungtsanpo River in eastern Tibet, and considered to be the eastern anchor of the Himalayas.

Outside the Himalayas and Karakorum, China's tallest peaks are Kongur Tagh (7649m, 37th) and Muztagh Ata (7546m, 43rd) in the Pamirs of western Xinjiang, Gongga Shan (7556m, 41st) in the Great Snowy Mountains of western Sichuan; and Tömür Shan (7,439m, 60th), the highest peak of Tian Shan, on the border with Kyrgyzstan.

Rivers and drainage

China has 50,000 rivers, each with a catchment area greater than 100 square kilometers. The rivers in China have a total length of 420,000 kilometers. 1,500 of Chinese rivers have a catchment area exceeding 1,000 square kilometers. The majority of rivers flow west to east into the Pacific Ocean. The Yangtze (Chang Jiang) rises in Tibet, flows through Central China and enters the East China Sea near Shanghai. The Yangtze is 6,300 kilometers long and has a catchment area of 1.8 million square kilometers. It is the third longest river in the world, after the Amazon and the Nile. The second longest river in China is the Huang He (Yellow River). It rises in Tibet and travels circuitously for 5,464 kilometers through North China, it empties into the Bo Hai Gulf on the north coast of the Shandong Province. It has a catchment area of 752,000 square kilometers. The Heilongjiang (Heilong or Black Dragon River) flows for 3,101 kilometers in Northeast China and an additional 1,249 kilometers in Russia, where it is known as the Amur. The longest river in South China is the Zhujiang (Pearl River), which is 2,214 kilometers long. Along with its three tributaries, the Xi (West), Dong (East), and Bei (North) rivers, it forms the Pearl River Delta near Guangzhou, Zhuhai, Macau, and Hong Kong. Other major rivers are the Liaohe in the northeast, Haihe in the north, Qiantang in the east, and Lancang in the southwest.

Inland drainage involving upland basins in the north and northeast accounts for 40 percent of the country's total drainage area. Many rivers and streams flow into lakes or diminish in the desert. Some are used for irrigation.

China's territorial waters are principally marginal seas of the western Pacific Ocean. These waters lie on the indented coastline of the mainland and approximately 5,000 islands. The Yellow Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea are marginal seas of the Pacific Ocean. More than half the coastline, predominantly in the south, is rocky; most of the remainder is sandy. The Bay of Hangzhou roughly divides the two kinds of shoreline.

- Northern plain

There is a steep drop in the river level in the North China Plain, where the river continues across the delta, it transports a heavy load of sand and mud which is deposited on the flat plain. The flow is aided by manmade embankments. As a result, the river flows on a raised ridge fifty meters above the plain. Waterlogging, floods, and course changes have recurred over the centuries. Traditionally, rulers were judged by their concern for or indifference to preservation of the embankments. In the modern era, China has undertaken extensive flood control and conservation measures.

Flowing from its source in the Qingzang highlands, the Yellow River courses toward the sea through the North China Plain, the historic center of Chinese expansion and influence. Han Chinese people have farmed the rich alluvial soils since ancient times, constructing the Grand Canal for north-south transport during the Imperial Era. The plain is a continuation of the Dongbei (Manchurian) Plain to the northeast but is separated from it by the Bohai Gulf, an extension of the Yellow Sea.

Like other densely populated areas of China, the plain is subject to floods and earthquakes. The mining and industrial center of Tangshan, 165 km east of Beijing, was leveled by an earthquake in July 1976, it was believed to be the largest earthquake of the 20th century by death toll.

The Hai River, like the Pearl River, flows from west to east. Its upper course consists of five rivers that converge near Tianjin, then flow seventy kilometers before emptying into the Bohai Gulf. The Huai River, rises in Henan Province and flows through several lakes before joining the Pearl River near Yangzhou.

- East and Yangtze

The Qin Mountains, a continuation of the Kunlun Mountains, divides the North China Plain from the Yangtze River Delta and is the major physiographic boundary between the two great parts of China Proper. It is a cultural boundary as it influences the distribution of customs and language. South of the Qinling mountain range divide are the densely populated and highly developed areas of the lower and middle plains of the Yangtze River and, on its upper reaches, the Sichuan Basin, an area encircled by a high barrier of mountain ranges.

The country's longest and most important waterway, the Yangtze River, is navigable for the majority of its length and has a vast hydroelectric potential. Rising on the Qingzang Plateau, the Yangtze River traverses 6,300 km through the heart of the country, draining an area of 1.8 million km² before emptying into the East China Sea. Roughly 300 million people live along its middle and lower reaches. The area is a large producer of rice and wheat. The Sichuan Basin, due to its mild, humid climate and long growing season, produces a variety of crops. It is a leading silk-producing area and an important industrial region with substantial mineral resources.

The Nanling Mountains, the southernmost of the east–west mountain ranges, overlook areas in China with a tropical climate. The climate allows two crops of rice to be grown per year. Southeast of the mountains lies a coastal, hilly region of small deltas and narrow valley plains. The drainage area of the Pearl River and its associated network of rivers occupies much of the region to the south. West of the Nanling, the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau rises in two steps, averaging 1,200 and 1,800 m in elevation, respectively, toward the precipitous mountain regions of the eastern Qingzang Plateau.

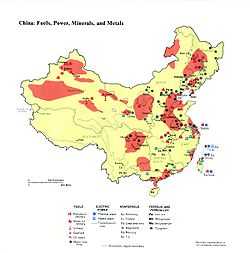

Geology and natural resources

China has substantial mineral reserves and is the world’s largest producer of antimony, natural graphite, tungsten, and zinc. Other major minerals are aluminum, bauxite, coal, crude petroleum, diamonds, gold, iron ore, lead, magnetite, manganese, mercury, molybdenum, natural gas, phosphate rock, tin, uranium, and vanadium. With its vast mountain ranges, China’s hydropower potential is the largest in the world.

Biology

Land use

Based on 2005 estimates, 14.86% (about 1.4 million km²) of China’s total land area is arable. About 1.3% (some 116,580 km²) is planted to permanent crops and the rest planted to temporary crops. With comparatively little land planted to permanent crops, intensive agricultural techniques are used to reap harvests that are sufficient to feed the world’s largest population and still have surplus for export. An estimated 544,784 km² of land were irrigated in 2004. 42.9% of total land area was used as pasture, and 17.5% was forest.

Wildlife

China lies in two of the world's major ecozones, the Palearctic and the Indomalaya. In the Palearctic zone are found such important mammals as the horse, camel, and jerboa. Among the species found in the Indomalaya region are the leopard cat, bamboo rat, treeshrew, and various other species of monkeys and apes. Some overlap exists between the two regions because of natural dispersal and migration, and deer or antelope, bears, wolves, pigs, and rodents are found in all of the diverse climatic and geological environments. The famous giant panda is found only in a limited area along the Chang Jiang. There is a continuing problem with trade in endangered species, although there are now laws to prohibit such activities.

Human geography

History

Chinese history is often explained in terms of several strategic areas, defined by particular topographic limits. Starting from the Chinese central plain, the former heart of the Han populations, the Han people expanded militarily and then demographically toward the Loess Plateau, the Sichuan Basin, and the Southern hills (as defined by the map on the left), not without resistance from local populations. Pushed by its comparatively higher demographic growth, the Han continued their expansion by military and demographic waves. The far-south of present-day China, the northern parts of today's Vietnam, and the Tarim Basin were first reached and durably subdued by the Han Dynasty's armies. The Northern steppes were always the source of invasions into China, which culminated in the 13th century by Mongolian conquest of the whole China and creation of Mongolian Yuan dynasty. Manchuria, much of today's Northeast China, and Korean Peninsula were usually not under Chinese control, with the exception of some limited periods of occupation. Manchuria became strongly integrated into the Chinese empire during the late Qing Dynasty, while the west side of the Changbai Mountains, formerly the home of Korean tribes, thus also entered China.

Demographic geography

The demographic occupation follows the topography and availability of former arable lands. The Heihe–Tengchong Line, running from Heihe, Heilongjiang to Tengchong County, Yunnan divides China into two roughly equal sections–in terms of geographic area, with areas west of the line being sparsely settled and areas east densely populated, in general.

Economic geography

| ||

| The East Coast (with existing development programmes) | ||

| "Rise of Central China" | ||

| "Revitalize Northeast China" | ||

| "China Western Development" | ||

China's economy has recently become export-oriented. The coastal provinces got the greatest benefits from the recent development of China's economy, becoming the new economic center of China. The Chinese leadership have long encouraged a move inland, and in 2012, following the western crisis, the top leadership announced a policy to redirect Chinese production toward the national market.

Administrative geography

Chinese administrative geography was drawn mainly during the 1949 and 1954 administrative reorganizations. These reorganizations have been the source of much debate within China. In addition, a parcel of land was ceded from Guangdong to Guangxi to grant the latter immediate access to the Gulf of Tonkin, while Hainan was split from Guangdong in 1988 and Chongqing from Sichuan in 1997.

Boundary disputes

- Central Asia

China's borders have more than 20,000 km (12,000 mi) of land frontier shared with nearly all the nations of mainland East Asia, and have been disputed at a number of points. In the western sector, China claimed portions of the 41,000 km2 (16,000 sq mi) Pamir Mountains area, a region of soaring mountain peaks and glacier filled valleys where the borders of Afghanistan, Pakistan, the former Soviet Union, and China meet in Central Asia. North and east of this region, some sections of the border remained undemarcated in 1987. The 6,542 kilometres (4,065 mi) frontier with the Soviet Union has been a source of continual friction. In 1954 China published maps showing substantial portions of Soviet Siberian territory as its own. In the northeast, border friction with the Soviet Union produced a tense situation in remote regions of Inner Mongolia and Heilongjiang along segments of the Argun River, Amur River, and Ussuri River. Each side had massed troops and had exchanged charges of border provocation in this area. In a September 1986 speech in Vladivostok, Soviet leader Mikhail S. Gorbachev offered the Chinese a more conciliatory position on Sino-Soviet border issues. In 1987 the two sides resumed border talks that had been broken off after the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan (see Sino-Soviet relations). Although the border issue remained unresolved as of late 1987, China and the Soviet Union agreed to consider the northeastern sector first. In October 2004, China signed an agreement with Russia on the delimitation of their entire 4,300 km (2,700 mi)-long border, which had long been in dispute.

- Southern border

Eastward from Bhutan and north of the Brahmaputra River (Yarlung Zangbo Jiang) lies a large area controlled and administered by India but claimed by the Chinese. The area was demarcated by the British McMahon Line, drawn along the Himalayas in 1914 as the Sino-Indian border; India accepts and China rejects this boundary. In June 1980 China made its first move in twenty years to settle the border disputes with India, proposing that India cede the Aksai Chin area in Jammu and Kashmir to China in return for China's recognition of the McMahon Line; India did not accept the offer, however, preferring a sector-by-sector approach to the problem. In July 1986 China and India held their seventh round of border talks, but they made little headway toward resolving the dispute. Each side, but primarily India, continued to make allegations of incursions into its territory by the other. Most of the mountainous and militarized boundary with India is still in dispute, but Beijing and New Delhi have committed to begin resolution with discussions on the least disputed middle sector. India does not recognize Pakistan’s ceding lands to China in a 1964 boundary agreement.

The China-Burma border issue was settled October 1, 1960, by the signing of the Sino-Burmese Boundary Treaty. The first joint inspection of the border was completed successfully in June 1986.

- Seas

China is involved in a complex dispute with Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam, and possibly Brunei over the Spratly (Nansha) Islands in the South China Sea. The 2002 "Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea" eased tensions but fell short of a legally binding code of conduct desired by several of the disputants. China also controls the Paracel (Xisha) Islands, which are also claimed by Vietnam, and asserts a claim to the Japanese-administered Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands in the East China Sea.

Atmosphere and pollution

Climate

Owing to tremendous differences in latitude, longitude, and altitude, the climate of China is extremely diverse, ranging from tropical in the far south to subarctic in the far north and alpine in the higher elevations of the Tibetan Plateau. Monsoon winds, caused by differences in the heat-absorbing capacity of the continent and the ocean, dominate the climate. During the summer, the East Asian Monsoon carries warm and moist air from the south and delivers the vast majority of the annual precipitation in much of the country. Conversely, the Siberian anticyclone dominates during winter, bringing cold and (comparatively) dry conditions. The advance and retreat of the monsoons account in large degree for the timing of the rainy season throughout the country. Although most of the country lies in the temperate belt, its climatic patterns are complex.

The northern extremities of both Heilongjiang and Inner Mongolia have a subarctic climate; in contrast, most of Hainan Island and parts of the extreme southern fringes of Yunnan has a tropical climate. Temperature differences in winter are considerable, but in summer the diversity is considerably less. For example, Mohe County, Heilongjiang has a 24-hour average temperature in January approaching −30 °C (−22 °F), while the corresponding figure in July exceeds 18 °C (64 °F). By contrast, most of Hainan has a January mean in excess of 17 °C (63 °F), while the July mean there is generally above 28 °C (82 °F). Extremes in temperature nationally have ranged from −52.3 °C (−62.1 °F) at Mohe County, Heilongjiang, up to 50.2 °C (122.4 °F) at Ayding Lake, Xinjiang.[4]

Precipitation is almost invariably concentrated in the warmer months, though annual totals range from less than 20 millimetres (0.8 in) in northwestern Qinghai and the Turpan Depression of Xinjiang to easily exceeding 2,000 millimetres (79 in) in Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan. Only in some pockets of the Dzungaria region of Xinjiang is the conspicuous seasonal variation in precipitation that defines Chinese (and, to a large extent, East Asian) climate absent.

Annual sunshine duration ranges from less than 1,100 hours in parts of Sichuan and Chongqing to over 3,400 hours in northwestern Qinghai. Seasonal patterns in sunshine vary considerably by region, but overall, the north and the Tibetan Plateau are sunnier than the south of the country.

-

.png)

The average annual precipitation across Greater China

-

Early-season snow covering part of the North China Plain near Shijiazhuang, Hebei

-

Snow encircling the area around the Bo Hai

-

The first day of spring 2010 brought a massive sandstorm blowing from Inner Mongolia

-

On November 11, 2010, a wall of sand blew across northern China, covering much of the North China Plain and Shandong Peninsula.

-

Smog from Eastern China spread over neighbouring areas in February 2004.

-

Haze over the North China Plain and the Lüliang Mountains of Shanxi

-

Natural colour satellite image of a smog event in the heart of northern China

-

Dense smog settled over the North China Plain on February 20, 2011.

Environment

Air pollution (sulfur dioxide particulates) from reliance on coal is a major issue, along with water pollution from untreated wastes and use of debated standards of pollutant concentration rather than Total Maximum Daily Load. There are water shortages, particularly in the north. The eastern part of China often experiences smoke and dense fog in the atmosphere as a result of industrial pollution. Heavy deforestation with an estimated loss of one-fifth of agricultural land since 1949 to soil erosion and economic development is occurring with resulting desertification. China is a party to the Antarctic-Environmental Protocol, the Antarctic Treaty, the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Climate Change treaty, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, the Endangered Species treaty, the Hazardous Wastes treaty, the Law of the Sea, the International Tropical Timber Agreements of 1983 and 1994, the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling, and agreements on Marine Dumping, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, and Wetlands protection. China has signed, but not ratified the Kyoto Protocol (but is not yet required to reduce its carbon emission under the agreement, as is India), and the Nuclear Test Ban treaty.

Antipodes

Most of coastal and western central China, including Beijing, are antipodal to Argentina and Chile. Wuhai, Inner Mongolia, for example, is antipodal to Valdivia, Chile. See Geography of Chile#Antipodes, Geography of Argentina#Antipodes, and Geography of Paraguay#Antipodes for details.

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ The CIA's The World Factbook gives 9,598,094 km2 ("CIA World Fact Book - Geography Note". CIA. Retrieved 2008-03-25.), the United Nations Statistics Division gives 9,629,091 km2 ("Population by Sex, Rate of Population Increase, Surface Area and Density" (PDF). Demographic Yearbook 2005. UN Statistics Division. Retrieved 2008-03-25.), and the Encyclopædia Britannica gives 9,522,055 km2.("United States". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-03-25.)

- ↑ CIA (October 1967), Communist China Map Folio, U.S. Central Intelligence Agency

- ↑ Mughal, Muhammad Aurang Zeb. 2013. "Pamir Alpine Desert and Tundra." Robert Warren Howarth (ed.), Biomes & Ecosystems, Vol. 3. Ipswich, MA: Salem Press, pp. 978-980.

- ↑ Extreme Temperatures Around the World - world highest lowest temperatures. Accessed 2010-11-02

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Geography of China. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maps of China. |

- (Chinese) Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources

- (Chinese) Chinese Ecosystem Research Network (CERN)

- (English) (Chinese) Illustrations of Famous Mountains from 1368-1644

| ||||||||||||||