Genetic drift

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

Diagrammatic representation of the divergence of modern taxonomic groups from their common ancestor. |

|

Natural history

|

|

History of evolutionary theory |

|

Fields and applications

|

|

Social implications |

|

Genetic drift (or allelic drift) is the change in the frequency of a gene variant (allele) in a population due to random sampling of organisms.[1] The alleles in the offspring are a sample of those in the parents, and chance has a role in determining whether a given individual survives and reproduces. A population's allele frequency is the fraction of the copies of one gene that share a particular form.[2] Genetic drift may cause gene variants to disappear completely and thereby reduce genetic variation.

When there are few copies of an allele, the effect of genetic drift is larger, and when there are many copies the effect is smaller. Vigorous debates occurred over the relative importance of natural selection versus neutral processes, including genetic drift. Ronald Fisher held the view that genetic drift plays at the most a minor role in evolution, and this remained the dominant view for several decades. In 1968, Motoo Kimura rekindled the debate with his neutral theory of molecular evolution, which claims that most instances where a genetic change spreads across a population (although not necessarily changes in phenotypes) are caused by genetic drift.[3]

Analogy with marbles in a jar

The process of genetic drift can be illustrated using 20 marbles in a jar to represent 20 organisms in a population.[4] Consider this jar of marbles as the starting population. Half of the marbles in the jar are red and half blue, and both colors correspond to two different alleles of one gene in the population. In each new generation the organisms reproduce at random. To represent this reproduction, randomly select a marble from the original jar and deposit a new marble with the same color as its "parent" into a new jar. (The selected marble remains in the original jar.) Repeat this process until there are 20 new marbles in the second jar. The second jar then contains a second generation of "offspring," consisting of 20 marbles of various colors. Unless the second jar contains exactly 10 red marbles and 10 blue marbles, a random shift occurred in the allele frequencies.

Repeat this process a number of times, randomly reproducing each generation of marbles to form the next. The numbers of red and blue marbles picked each generation fluctuates: sometimes more red, sometimes more blue. This fluctuation is analogous to genetic drift – a change in the population's allele frequency resulting from a random variation in the distribution of alleles from one generation to the next.

It is even possible that in any one generation no marbles of a particular color are chosen, meaning they have no offspring. In this example, if no red marbles are selected the jar representing the new generation contains only blue offspring. If this happens, the red allele has been lost permanently in the population, while the remaining blue allele has become fixed: all future generations are entirely blue. In small populations, fixation can occur in just a few generations.

Probability and allele frequency

The mechanisms of genetic drift can be illustrated with a simplified example. Consider a very large colony of bacteria isolated in a drop of solution. The bacteria are genetically identical except for a single gene with two alleles labeled A and B. A and B are neutral alleles meaning that they do not affect the bacteria's ability to survive and reproduce; all bacteria in this colony are equally likely to survive and reproduce. Suppose that half the bacteria have allele A and the other half have allele B. Thus A and B each have allele frequency 1/2.

The drop of solution then shrinks until it has only enough food to sustain four bacteria. All other bacteria die without reproducing. Among the four who survive, there are sixteen possible combinations for the A and B alleles:

(A-A-A-A), (B-A-A-A), (A-B-A-A), (B-B-A-A),

(A-A-B-A), (B-A-B-A), (A-B-B-A), (B-B-B-A),

(A-A-A-B), (B-A-A-B), (A-B-A-B), (B-B-A-B),

(A-A-B-B), (B-A-B-B), (A-B-B-B), (B-B-B-B).

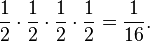

Since all bacteria in the original solution are equally likely to survive when the solution shrinks, the four survivors are a random sample from the original colony. The probability that each of the four survivors has a given allele is 1/2, and so the probability that any particular allele combination occurs when the solution shrinks is

(The original population size is so large that the sampling effectively happens without replacement). In other words, each of the sixteen possible allele combinations is equally likely to occur, with probability 1/16.

Counting the combinations with the same number of A and B, we get the following table.

| A | B | Combinations | Probability |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 1/16 |

| 3 | 1 | 4 | 4/16 |

| 2 | 2 | 6 | 6/16 |

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 4/16 |

| 0 | 4 | 1 | 1/16 |

As shown in the table, the total number of possible combinations to have an equal (conserved) number of A and B alleles is six, and its probability is 6/16. The total number of possible alternative combinations is ten, and the probability of unequal number of A and B alleles is 10/16. Thus, although the original colony began with an equal number of A and B alleles, chances are that the number of alleles in the remaining population of four members will not be equal. In the latter case, genetic drift has occurred because the population's allele frequencies have changed due to random sampling. In this example the population contracted to just four random survivors, a phenomenon known as population bottleneck.

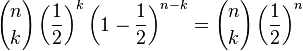

Note that the probabilities for the number of copies of allele A (or B) that survive (given in the last column of the above table) can calculated directly from the Binomial distribution where the "success" probability (probability of a given allele being present) is 1/2 i.e. the probability that there are k copies of A (or B) alleles in the combination is given by

where n=4 is the number of surviving bacteria.

Mathematical models of genetic drift

Mathematical models of genetic drift can be designed using either branching processes or a diffusion equation describing changes in allele frequency in an idealised population.[5]

Wright–Fisher model

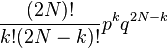

Consider a gene with two alleles, A or B. In diploid populations consisting of N individuals there are 2N copies of each gene. An individual can have two copies of the same allele or two different alleles. We can call the frequency of one allele p and the frequency of the other q. The Wright–Fisher model (named after Sewall Wright and Ronald Fisher) assumes that generations do not overlap (for example, annual plants have exactly one generation per year) and that each copy of the gene found in the new generation is drawn independently at random from all copies of the gene in the old generation. The formula to calculate the probability of obtaining k copies of an allele that had frequency p in the last generation is then[6][7]

where the symbol "!" signifies the factorial function. This expression can also be formulated using the binomial coefficient,

Moran model

The Moran model assumes overlapping generations. At each time step, one individual is chosen to reproduce and one individual is chosen to die. So in each timestep, the number of copies of a given allele can go up by one, go down by one, or can stay the same. This means that the transition matrix is tridiagonal, which means that mathematical solutions are easier for the Moran model than for the Wright–Fisher model. On the other hand, computer simulations are usually easier to perform using the Wright–Fisher model, because fewer time steps need to be calculated. In the Moran model, it takes N timesteps to get through one generation, where N is the effective population size. In the Wright–Fisher model, it takes just one.

In practice, the Moran model and Wright–Fisher model give qualitatively similar results, but genetic drift runs twice as fast in the Moran model.

Other models of drift

If the variance in the number of offspring is much greater than that given by the binomial distribution assumed by the Wright–Fisher model, then given the same overall speed of genetic drift (the variance effective population size), genetic drift is a less powerful force compared to selection.[8] Even for the same variance, if higher moments of the offspring number distribution exceed those of the binomial distribution then again the force of genetic drift is substantially weakened.[9]

Random effects other than sampling error

Random changes in allele frequencies can also be caused by effects other than sampling error, for example random changes in selection pressure.[10]

One important alternative source of stochasticity, perhaps more important than genetic drift, is genetic draft.[11] Genetic draft is the effect on a locus by selection on linked loci. The mathematical properties of genetic draft are different from those of genetic drift.[12] The direction of the random change in allele frequency is autocorrelated across generations.[1]

Drift and fixation

The Hardy–Weinberg principle states that within sufficiently large populations, the allele frequencies remain constant from one generation to the next unless the equilibrium is disturbed by migration, genetic mutations, or selection.[13]

However, in finite populations, no new alleles are gained from the random sampling of alleles passed to the next generation, but the sampling can cause an existing allele to disappear. Because random sampling can remove, but not replace, an allele, and because random declines or increases in allele frequency influence expected allele distributions for the next generation, genetic drift drives a population towards genetic uniformity over time. When an allele reaches a frequency of 1 (100%) it is said to be "fixed" in the population and when an allele reaches a frequency of 0 (0%) it is lost. Smaller populations achieve fixation faster, whereas in the limit of an infinite population, fixation is not achieved. Once an allele becomes fixed, genetic drift comes to a halt, and the allele frequency cannot change unless a new allele is introduced in the population via mutation or gene flow. Thus even while genetic drift is a random, directionless process, it acts to eliminate genetic variation over time.[14]

Rate of allele frequency change due to drift

Assuming genetic drift is the only evolutionary force acting on an allele, after t generations in many replicated populations, starting with allele frequencies of p and q, the variance in allele frequency across those populations is

Time to fixation or loss

Assuming genetic drift is the only evolutionary force acting on an allele, at any given time the probability that an allele will eventually become fixed in the population is simply its frequency in the population at that time.[16] For example, if the frequency p for allele A is 75% and the frequency q for allele B is 25%, then given unlimited time the probability A will ultimately become fixed in the population is 75% and the probability that B will become fixed is 25%.

The expected number of generations for fixation to occur is proportional to the population size, such that fixation is predicted to occur much more rapidly in smaller populations.[17] Normally the effective population size, which is smaller than the total population, is used to determine these probabilities. The effective population (Ne) takes into account factors such as the level of inbreeding, the stage of the lifecycle in which the population is the smallest, and the fact that some neutral genes are genetically linked to others that are under selection.[8] The effective population size may not be the same for every gene in the same population.[18]

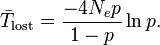

One forward-looking formula used for approximating the expected time before a neutral allele becomes fixed through genetic drift, according to the Wright–Fisher model, is

where T is the number of generations, Ne is the effective population size, and p is the initial frequency for the given allele. The result is the number of generations expected to pass before fixation occurs for a given allele in a population with given size (Ne) and allele frequency (p).[19]

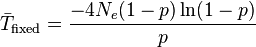

The expected time for the neutral allele to be lost through genetic drift can be calculated as[6]

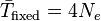

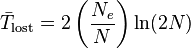

When a mutation appears only once in a population large enough for the initial frequency to be negligible, the formulas can be simplified to[20]

for average number of generations expected before fixation of a neutral mutation, and

for the average number of generations expected before the loss of a neutral mutation.[21]

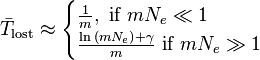

Time to loss with both drift and mutation

The formulae above apply to an allele that is already present in a population, and which is subject to neither mutation nor selection. If an allele is lost by mutation much more often than it is gained by mutation, then mutation, as well as drift, may influence the time to loss. If the allele prone to mutational loss begins as fixed in the population, and is lost by mutation at rate m per replication, then the expected time in generations until its loss in a haploid population is given by

where  is equal to Euler's constant.[22] The first approximation represents the waiting time until the first mutant destined for loss, with loss then occurring relatively rapidly by genetic drift, taking time Ne<<1/m. The second approximation represents the time needed for deterministic loss by mutation accumulation. In both cases, the time to fixation is dominated by mutation via the term 1/m, and is less affected by the effective population size.

is equal to Euler's constant.[22] The first approximation represents the waiting time until the first mutant destined for loss, with loss then occurring relatively rapidly by genetic drift, taking time Ne<<1/m. The second approximation represents the time needed for deterministic loss by mutation accumulation. In both cases, the time to fixation is dominated by mutation via the term 1/m, and is less affected by the effective population size.

Genetic drift versus natural selection

The law of large numbers predicts that when the population is large, the effect of genetic drift is much milder. When the reproductive population is small, however, the effects of sampling error can alter the allele frequencies significantly. Genetic drift is therefore considered to be a consequential mechanism of evolutionary change primarily within small, isolated populations.[23]

Although both processes affect evolution, genetic drift operates randomly while natural selection functions non-randomly. While natural selection has a direction, guiding evolution towards heritable adaptations to the current environment, genetic drift has no direction and is guided only by the mathematics of chance.[24] As a result, drift acts upon the genotypic frequencies within a population without regard to their phenotypic effects. In contrast, selection favors the spread of alleles whose phenotypic effects increase survival and/or reproduction of their carriers, lowers the frequencies of alleles that cause unfavorable traits, and ignores those that are neutral.[25]

In natural populations, genetic drift and natural selection do not act in isolation; both forces are always at play, together with mutation and migration. However, the magnitude of drift on allele frequencies per generation is larger when the absolute number of copies of the allele is small, e.g. in small populations. The magnitude of drift is large enough to overwhelm selection when the selection coefficient is less than 1 divided by the effective population size.

The mathematics of genetic drift depend on the effective population size, but it is not clear how this is related to the actual number of individuals in a population.[11] Genetic linkage to other genes that are under selection can reduce the effective population size experienced by a neutral allele. With a higher recombination rate, linkage decreases and with it this local effect on effective population size.[26][27] This effect is visible in molecular data as a correlation between local recombination rate and genetic diversity,[28] and negative correlation between gene density and diversity at noncoding sites.[29] Stochasticity associated with linkage to other genes that are under selection is not the same as sampling error, and is sometimes known as genetic draft in order to distinguish it from genetic drift.[11]

When the allele frequency is very small, drift can also overpower selection even in large populations. For example, while disadvantageous mutations are usually eliminated quickly in large populations, new advantageous mutations are almost as vulnerable to loss through genetic drift as are neutral mutations. Not until the allele frequency for the advantageous mutation reaches a certain threshold will genetic drift have no effect.[25]

In general, "global" solutions to many adaptive challenges at once can evolve at a smaller effective population size than "local" solutions that must evolve separately to each adaptive challenge.[30]

Population bottleneck

A population bottleneck is when a population contracts to a significantly smaller size over a short period of time due to some random environmental event.[31] In a true population bottleneck, the odds for survival of any member of the population are purely random, and are not improved by any particular inherent genetic advantage. The bottleneck can result in radical changes in allele frequencies, completely independent of selection.

The impact of a population bottleneck can be sustained, even when the bottleneck is caused by a one-time event such as a natural catastrophe. An interesting example of a bottleneck causing unusual genetic distribution is the relatively high proportion of individuals with total rod color-blindness (achromatopsia) on Pingelap atoll in Micronesia. After a bottleneck, inbreeding increases. This increases the damage done by recessive deleterious mutations, in a process known as inbreeding depression. The worst of these mutations are selected against, leading to the loss of other alleles that are genetically linked to them, in a process of background selection.[1] For recessive harmful mutations, this selection can be enhanced as a consequence of the bottleneck, due to genetic purging.This leads to a further loss of genetic diversity. In addition, a sustained reduction in population size increases the likelihood of further allele fluctuations from drift in generations to come.

A population's genetic variation can be greatly reduced by a bottleneck, and even beneficial adaptations may be permanently eliminated.[32] The loss of variation leaves the surviving population vulnerable to any new selection pressures such as disease, climate change or shift in the available food source, because adapting in response to environmental changes requires sufficient genetic variation in the population for natural selection to take place.[33][34]

There have been many known cases of population bottleneck in the recent past. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, North American prairies were habitat for millions of greater prairie chickens. In Illinois alone, their numbers plummeted from about 100 million birds in 1900 to about 50 birds in the 1990s. The declines in population resulted from hunting and habitat destruction, but the random consequence has been a loss of most of the species' genetic diversity. DNA analysis comparing birds from the mid century to birds in the 1990s documents a steep decline in the genetic variation in just in the latter few decades. Currently the greater prairie chicken is experiencing low reproductive success.[35]

Over-hunting also caused a severe population bottleneck in the northern elephant seal in the 19th century. Their resulting decline in genetic variation can be deduced by comparing it to that of the southern elephant seal, which were not so aggressively hunted.[36]

Founder effect

The founder effect is a special case of a population bottleneck, occurring when a small group in a population splinters off from the original population and forms a new one. The random sample of alleles in the just formed new colony is expected to grossly misrepresent the original population in at least some respects.[37] It is even possible that the number of alleles for some genes in the original population is larger than the number of gene copies in the founders, making complete representation impossible. When a newly formed colony is small, its founders can strongly affect the population's genetic make-up far into the future.

A well documented example is found in the Amish migration to Pennsylvania in 1744. Two members of the new colony shared the recessive allele for Ellis–van Creveld syndrome. Members of the colony and their descendants tend to be religious isolates and remain relatively insular. As a result of many generations of inbreeding, Ellis-van Creveld syndrome is now much more prevalent among the Amish than in the general population.[25][38]

The difference in gene frequencies between the original population and colony may also trigger the two groups to diverge significantly over the course of many generations. As the difference, or genetic distance, increases, the two separated populations may become distinct, both genetically and phenetically, although not only genetic drift but also natural selection, gene flow, and mutation contribute to this divergence. This potential for relatively rapid changes in the colony's gene frequency led most scientists to consider the founder effect (and by extension, genetic drift) a significant driving force in the evolution of new species. Sewall Wright was the first to attach this significance to random drift and small, newly isolated populations with his shifting balance theory of speciation.[39] Following after Wright, Ernst Mayr created many persuasive models to show that the decline in genetic variation and small population size following the founder effect were critically important for new species to develop.[40] However, there is much less support for this view today since the hypothesis has been tested repeatedly through experimental research and the results have been equivocal at best.[41] Founder effect was first well investigated in USSR by Soviet scientists Lisovskiy V.V., Kuznetsov M.A. and Nikolay Dubinin.

History of the concept

The concept of genetic drift was first introduced by one of the founders in the field of population genetics, Sewall Wright. His first use of the term "drift" was in 1929,[42] though at the time he was using it in the sense of a directed process of change, or natural selection. Random drift by means of sampling error came to be known as the "Sewall–Wright effect," though he was never entirely comfortable to see his name given to it. Wright referred to all changes in allele frequency as either "steady drift" (e.g. selection) or "random drift" (e.g. sampling error).[43] "Drift" came to be adopted as a technical term in the stochastic sense exclusively.[44] Today it is usually defined still more narrowly, in terms of sampling error,[45] although this narrow definition is not universal.[46][47] Wright wrote that the "restriction of "random drift" or even "drift" to only one component, the effects of accidents of sampling, tends to lead to confusion."[43] Sewall Wright considered the process of random genetic drift by means of sampling error equivalent to that by means of inbreeding, but later work has shown them to be distinct.[48]

In the early days of the modern evolutionary synthesis, scientists were just beginning to blend the new science of population genetics with Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection. Working within this new framework, Wright focused on the effects of inbreeding on small relatively isolated populations. He introduced the concept of an adaptive landscape in which phenomena such as cross breeding and genetic drift in small populations could push them away from adaptive peaks, which in turn allow natural selection to push them towards new adaptive peaks.[49] Wright thought smaller populations were more suited for natural selection because "inbreeding was sufficiently intense to create new interaction systems through random drift but not intense enough to cause random nonadaptive fixation of genes."[44]

Wright's views on the role of genetic drift in the evolutionary scheme were controversial almost from the very beginning. One of the most vociferous and influential critics was colleague Ronald Fisher. Fisher conceded genetic drift played some role in evolution, but an insignificant one. Fisher has been accused of misunderstanding Wright's views because in his criticisms Fisher seemed to argue Wright had rejected selection almost entirely. To Fisher, viewing the process of evolution as a long, steady, adaptive progression was the only way to explain the ever-increasing complexity from simpler forms. But the debates have continued between the "gradualists" and those who lean more toward the Wright model of evolution where selection and drift together play an important role.[50]

In 1968,[51] population geneticist Motoo Kimura rekindled the debate with his neutral theory of molecular evolution, which claims that most of the genetic changes are caused by genetic drift acting on neutral mutations.[3]

The role of genetic drift by means of sampling error in evolution has been criticized by John H Gillespie[52] and Will Provine, who argue that selection on linked sites is a more important stochastic force.

See also

- Allopatric speciation

- Antigenic drift

- Gene pool

- Small population size

- Neutral theory of molecular evolution

- Coalescent theory

- Fixation

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Masel J (2011). "Genetic drift". Current Biology 21 (20): R837–R838. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.007. PMID 22032182.

- ↑ Futuyma, Douglas (1998). Evolutionary Biology. Sinauer Associates. p. Glossary. ISBN 0-87893-189-9.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Futuyma, Douglas (1998). Evolutionary Biology. Sinauer Associates. p. 320. ISBN 0-87893-189-9.

- ↑ "Evolution 101:Sampling Error and Evolution". University of California Berkeley. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ Wahl L.M. (2011). "Fixation when N and s Vary: Classic Approaches Give Elegant New Results". Genetics 188 (4): 783–785. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.131748. PMC 3176088. PMID 21828279.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Daniel Hartl, Andrew Clark (2007). Principles of Population Genetics (4th ed.). Sinauer Associates. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-87893-308-2.

- ↑ Tian, Jianjun Paul (2008). Evolution algebras and their applications. Lecture Notes in Mathematics 1921. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-540-74283-8. Zbl 1136.17001.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Charlesworth B (March 2009). "Fundamental concepts in genetics: Effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation". Nat. Rev. Genet. 10 (3): 195–205. doi:10.1038/nrg2526. PMID 19204717.

- ↑ Der R, Epstein CL, Plotkin JB (2011). "Generalized population models and the nature of genetic drift". Theoretical Population Biology 80 (2): 80–99. doi:10.1016/j.tpb.2011.06.004. PMID 21718713.

- ↑ Li, Wen-Hsiung; Dan Graur (1991). Fundamentals of Molecular Evolution. Sinauer Associates. p. 28. ISBN 0-87893-452-9.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Gillespie, John H. (2001). "Is the population size of a species relevant to its evolution?". Evolution 55 (11): 2161–2169. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00732.x. PMID 11794777.

- ↑ R.A. Neher and B.I. Shraiman (2011). "Genetic Draft and Quasi-Neutrality in Large Facultatively Sexual Populations". Genetics 188 (4): 975–996. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.128876. PMC 3176096. PMID 21625002.

- ↑ Warren Ewens (2004). Mathematical Population Genetics I. Theoretical Introduction. Interdisciplinary Applied Mathematics. Springer-Verlag.

- ↑ Li, Wen-Hsiung; Dan Graur (1991). Fundamentals of Molecular Evolution. Sinauer Associates. p. 29. ISBN 0-87893-452-9.

- ↑ Nicholas H. Barton, Derek E. G. Briggs, Jonathan A. Eisen, David B. Goldstein, Nipam H. Patel (2007). Evolution. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. p. 417. ISBN 0-87969-684-2.

- ↑ Futuyma, Douglas (1998). Evolutionary Biology. Sinauer Associates. p. 300. ISBN 0-87893-189-9.

- ↑ Otto S, Whitlock M (1 June 1997). "The Probability of Fixation in Populations of Changing Size". Genetics 146 (2): 723–33. PMC 1208011. PMID 9178020.

- ↑ Asher D. Cutter and Jae Young Choi (2010). "Natural selection shapes nucleotide polymorphism across the genome of the nematode Caenorhabditis briggsae". Genome Research 20 (8): 1103–1111. doi:10.1101/gr.104331.109. PMC 2909573. PMID 20508143.

- ↑ Hedrick, Philip W. (2004). Genetics of Populations. Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 737. ISBN 0-7637-4772-6.

- ↑ Li, Wen-Hsiung; Graur, Dan (1991). Fundamentals of Molecular Evolution. Sinauer Associates. p. 33. ISBN 0-87893-452-9.

- ↑ Kimura, Motoo; Ohta, Tomoko (2001). Theoretical Aspects of Population Genetics. Princeton University Press. p. 232. ISBN 0-691-08098-4.

- ↑ Masel J, King OD, Maughan H (2007). "The loss of adaptive plasticity during long periods of environmental stasis". American Naturalist 169 (1): 38–46. doi:10.1086/510212. PMC 1766558. PMID 17206583.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (2002). Evolution : The Triumph of an Idea. New York, NY: Perennial. p. 364. ISBN 0-06-095850-2.

- ↑ "Natural Selection: How Evolution Works (An interview with Douglas Futuyma, see answer to question Is natural selection the only mechanism of evolution?)". ActionBioscience.org. Retrieved 2009-11-24.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Cavalli-Sforza, L. L.; Menozzi, Paolo; Piazza, Alberto (1996). The history and geography of human genes. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 413. ISBN 0-691-02905-9.

- ↑ Golding B (1994). Non-neutral evolution: theories and molecular data. Springer. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-412-05391-7.

- ↑ Charlesworth B, Morgan MT, Charlesworth D (August 1993). "The Effect of Deleterious Mutations on Neutral Molecular Variation". Genetics 134 (4): 1289–303. PMC 1205596. PMID 8375663.

- ↑ Presgraves DC (September 2005). "Recombination enhances protein adaptation in Drosophila melanogaster". Curr. Biol. 15 (18): 1651–6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.065. PMID 16169487.

- ↑ Nordborg M, Hu TT, Ishino Y et al. (July 2005). "The Pattern of Polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana". PLoS Biol. 3 (7): e196. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030196. PMC 1135296. PMID 15907155.

- ↑ Rajon, E., Masel, J. (2011). "Evolution of molecular error rates and the consequences for evolvability". PNAS 108 (3): 1082–1087. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012918108. PMC 3024668. PMID 21199946.

- ↑ Population Bottleneck | Macmillan Genetics

- ↑ Futuyma, Douglas (1998). Evolutionary Biology. Sinauer Associates. pp. 303–304. ISBN 0-87893-189-9.

- ↑ O'Corry-Crowe G (2008). "Climate change and the molecular ecology of arctic marine mammals". Ecological Applications 18 (2 Suppl): S56–S76. doi:10.1890/06-0795.1. PMID 18494363.

- ↑ Cornuet JM, Luikart G (1996). "Description and Power Analysis of Two Tests for Detecting Recent Population Bottlenecks from Allele Frequency Data". Genetics 144 (4): 2001–14. PMC 1207747. PMID 8978083.

- ↑ Hillis, David M.; Sadava, David E.; Heller, Craig H.; Orians, Gordon H.; Purves, William K. (2006). "Chs. 1, 21–33, 52–57". Life: The Science of Biology. II: Evolution, Diversity and Ecology. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. p. 1251. ISBN 978-0-7167-9856-9.

- ↑ "Evolution 101: Bottlenecks and Founder Effects". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- ↑ Neill, Campbell (1996). Biology; Fourth edition. The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company. p. 423. ISBN 0-8053-1940-9.

- ↑ "Genetic Drift and the Founder Effect". Evolution. Public Broadcast System. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- ↑ Wade, Michael S.; Wolf, Jason; Brodie, Edmund D. (2000). Epistasis and the evolutionary process. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. p. 330. ISBN 0-19-512806-0.

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst, Jody Hey, Walter M. Fitch, Francisco José Ayala (2005). Systematics and the Origin of Species: on Ernst Mayr's 100th anniversary (Illustrated ed.). National Academies Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-309-09536-5.

- ↑ Howard, Daniel J.; Berlocher, Steward H. (1998). Endless Forms (Illustrated ed.). United States: Oxford University Press. p. 470. ISBN 978-0-19-510901-6.

- ↑ Wright S (1929). "The evolution of dominance". The American Naturalist 63 (689): 556–61. doi:10.1086/280290.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Wright S (1955). "Classification of the factors of evolution" (PDF). Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 20: 16–24. doi:10.1101/SQB.1955.020.01.004.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Stevenson, Joan C. (1991). Dictionary of Concepts in Physical Anthropology. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-24756-0.

- ↑ Freeman and Herron. Evolutionary Analysis. 2007. Pearson Education, NJ. p.801

- ↑ Masel, Joanna (2012). "Rethinking Hardy–Weinberg and genetic drift in undergraduate biology". BioEssays 34 (8): 701–10. doi:10.1002/bies.201100178. PMID 22576789.

- ↑ Lynch, Michael (2007). The Origins of Genome Architecture. Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-484-7.

- ↑ James F. Crow (2010). "Wright and Fisher on Inbreeding and Random Drift". Genetics 184 (3): 609–611. doi:10.1534/genetics.109.110023. PMC 2845331. PMID 20332416.

- ↑ Larson, Edward J. (2004). Evolution: The Remarkable History of a Scientific Theory. Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-679-64288-6.

- ↑ Avers, Charlotte (1989). Process and Pattern in Evolution. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505275-7.

- ↑ Kimura M (1968). "Evolutionary rate at the molecular level". Nature 217 (5129): 624–26. doi:10.1038/217624a0. PMID 5637732.

- ↑ Gillespie JH (2000). "Genetic drift in an infinite population. The pseudohitchhiking model". Genetics 155 (2): 909–919. PMC 1461093. PMID 10835409.

External links

- The TalkOrigins Archive

- Genetic drift illustrations in Barton et al.

- Drift vs. draft

- Online simulation of genetic drift

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||