General sejm

The general sejm (Polish: sejm walny, also translated as the full or ordinary sejm) was the parliament of Poland for four centuries from the 15th until the late 18th century. It had evolved from the earlier institution of wiec. It was one of the primary elements of the democratic governance in the Kingdom of Poland and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The sejm was a powerful political institution, and from early 16th century, the Polish king could not pass laws without the approval of that body.

Duration and frequencies of the sejms changed over time, with the six-week sejm session convened every two years being most common. Sejm locations changed throughout history, eventually with the Commonwealth capital of Warsaw emerging as the primary location. The number of sejm deputies and senators grew over time, from about 70 senators and 50 deputies in the 15th century to about 150 senators and 200 deputies in the 18th century. Early sejms have seen mostly majority voting, but beginning in the 17th century, unanimous voting became more common, and 32 sejms were vetoed with the infamous liberum veto, particularly in the first half of the 18th century. This vetoing procedure has been credited with significantly paralyzing the Commonwealth governance.

In addition to the regular sessions of the general sejm, in the era of electable kings, beginning in 1573, three special types of sejms handled the process of the royal election in the interregnum period. It is estimated that between 1493 and 1793 sejms were held about 240 times.

Etymology

The word sejm and sejmik are derived from old Czech sejmovat, which means "to bring together" or "to summon".[1] In English, the terms general,[2] full[3] or ordinary[4] sejm are used for the sejm walny.

Genesis

There is no obvious date for the first sejm. Public participation in policy making in Poland can be traced to the Slavic assembly known as the wiec.[5] Another form of public decision making was that of royal election, which occurred when there was no clear heir to the throne, or the heir's appointment had to be confirmed.[6] There are legends of a 9th-century election of the legendary founder of the Piast dynasty, Piast the Wheelwright, and a similar election of his son, Siemowit (this would place a Polish ruler's election a century before an Icelandic one's by the Althing), but sources for that time come from the later centuries and their validity is disputed by scholars.[7][8] The election privilege was usually limited to the most powerful nobles (magnates) or officials, and was heavily influenced by local traditions and strength of the ruler.[6] By the 12th or 13th centuries, the wiec institution likewise limited its participation to high ranking nobles and officials.[9] The nationwide gatherings of wiec officials in 1306 and 1310 can be seen as precursors of the general sejm.[9]

The traditions of local wiec's or sejmiks survived the period of Poland's fragmentation (1146–1295), and continued in the restored Kingdom of Poland.[10][11] Sejmiks proper date to the late 14th century when they arose from gatherings of nobility, formed for military and consultative purposes.[1] Sejmiks were legally recognized by the 1454 Nieszawa Statutes, in a privilege granted to the szlachta (Polish nobility) by King Casimir IV Jagiellon, when the King agreed to consult certain decisions with the nobility.[1][12][13] Such local gatherings were preferred by the kings, as national assemblies would try to claim more power than the regional ones.[10][14] Nonetheless, with time the power of such assemblies grew, entrenched with milestone privileges obtained by the szlachta particularly during periods of transition from one dynasty or royal succession system to another (such as the Privilege of Koszyce of 1374).[14]

According to some older historians, such as Zygmunt Gloger or Tadeusz Czacki,[15][16][17] the first sejm took place in 1180, the date of the gathering of notables (zjazd, translated as an assembly,[18] congress[19] or synod[20]) at Łęczyca, shown on a painting of Jan Matejko entitled "The First Sejm".[21] More modern works however do not refer to the Łęczyca gathering as a sejm and instead focus on the more regular national gatherings that became known as sejm walny or sejm wielki and date to the 15th century.[10][22] Whereas Bardach in discussing the beginning of sejm walny points to the national assemblies of the early 15th century, Jędruch prefers, as "a convenient time marker", the sejm of 1493, the first recorded bicameral session of the Polish parliament (although as noted by Sedlar, 1493 is simply the first time such a session was clearly recorded in sources, and the first bicameral session might have taken place earlier).[10][14][22][23]

The Polish–Lithuanian union also spread the institution of a sejm to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. After a period in which Lithuanian delegations participated in the sejm of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, the first sejm in the Grand Duchy took place in Vilnius in 1528.[24]

Duration and frequency

In the mid-15th century the general sejm met about once per year.[10] There was no set time span to elapse before the next session was to be called by the king.[23] If the general sejm did not happen, local sejmiks would debate on current issues instead.[10] King Henry's Articles, signed by each king since 1573, required the king to call a general sejm (lasting six weeks) every two years, and provisions for an extraordinary sejm (Polish: sejm ekstraordynaryjny, nadzwyczajny) that was to last two weeks were also set down in this act.[25][26] Extraordinary sejms could be called in times of national emergency, for example a sejm deciding whether to call pospolite ruszenie (a general call to arms) in response to an invasion. The sejm could be extended if all the deputies agreed.[26]

No set time of a year was defined, but customarily sejms were called for a time that would not interfere with the supervision of agriculture, which formed the livelihood of most nobility; thus most sejms took place in late fall or early winter.[25]

After the Constitution of May 3, 1791, sejms were to be held every two years and last 70 days, with a provision for an extension to 100 days.[27] Provisions for extraordinary sejms were made, as well as for a special constitutional sejm, which was to meet and discuss whether any revisions to the constitution were needed (that one was to deliberate every 25 years).[27]

It is estimated that between 1493 and 1793 sejms were held 240 times.[28] Jędruch gives a higher number of 245, and notes that 192 of those were successfully completed, passing legislation.[25] 32 sejms were vetoed with the infamous liberum veto, particularly in the first half of the 18th century.[25] The last two sejms of the Commonwealth were the irregular four-year Great Sejm (1788-1792), which passed the Constitution of the 3 May, and the infamous Grodno Sejm (1793), whose deputies, bribed or coerced by the Russian Empire following the Commonwealth defeat in the War in Defense of the Constitution, annulled the short-lived Constitution and passed the act of Second Partition of Poland.[29][30]

Political influence

Sejms, including their senate (the upper chamber), and sejmiks severely limited the king's powers. The king could not pass laws himself without the approval of the sejm, this being forbidden by szlachta privilege laws like nihil novi from 1505.[31] According to the nihil novi constitution, a law passed by the sejm had to be agreed by the three estates (stany sejmujące; the king, the senate and deputies from the sejm proper - the lower chamber).[31] There were only few areas in which the king could pass legislation without consulting the sejm: on royal cities, peasants in royal lands, Jews, fiefs and on mining.[31] The three estates of the sejm had the final decision in legislation on taxation, budget and treasury matters (including military funding), foreign affairs (including hearing foreign envoys and sending diplomatic missions) and ennoblement.[10][31] The sejm received fiscal reports from deputy treasurers, and debated on most important court cases (the sejm court), with the right of amnesty.[31] The sejm could also legislate in the absence of the king, although such legislation would have to be accepted by the king ex post.[10]

Following the Constitution of May 3, 1791, the senate's competences were altered; in most cases the senators could only vote together with the sejm, and the senate's veto powers were limited.[27] Legislative power was limited to the deputies of the sejm (not senators voting separately, except on the senate's privilege of veto, a suspension of a given legislation until the sejm votes on it again during the next session). The king, who nominated senators, ministers and other officials, presided over the senate, and could propose new laws together with the executive government, over which he also presided (the newly created Straż Praw or the Guardianship of Laws).[27] The sejm also had the supervisory role, as government ministers and other officials were to be responsible to it.[27]

Proceedings

A sejm began with a solemn mass, a verification of deputies mandates, and election of the Marshal of the Sejm (also known as the Speaker).[32][33] (The position of the Marshal of the Sejm (and sejmik) who presided over the proceedings and was elected from the body of deputies evolved in the 17th century.[10]) Next, the kanclerz (chancellor) declared the king's intentions to both chambers, who would then debate separately till the ending ceremonies.[33]

After 1543 the resolutions were written in Polish rather than Latin.[34] All legislation adopted by a given sejm formed a whole and was published as a "constitution" of the sejm, e.g. the constitution of 1667. From the end of the 16th century, the constitutions were printed, stamped with the royal seal, and sent to the chancelleries of the municipal councils of all voivodeships of the Crown and also to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[35][36] Such constitutions were often subjected to some final tweaking by the royal court before being printed, although that could lead to protests among the nobility.[35]

Voting

Until the end of the 16th century, unanimity was not required and majority voting predominated.[25][35] Later, with the rise of the magnates' power, the unanimity principle was enforced with the szlachta privilege of liberum veto (from the Latin: "I freely forbid").[37] From the second half of the 17th century, the liberum veto was used to paralyze sejm proceedings and brought the Commonwealth to the brink of collapse.[35][38] The growing power of sejmiks also contributed to the inefficiency of the sejm, as binding instructions from sejmiks could prevent some deputies from being able to support certain provisions.[35][39] The pro-majority-voting party almost disappeared in the 17th century, and majority voting was preserved only at confederated sejms (sejm rokoszowy, konny, konfederacyjny).[25] The liberum veto was finally abolished by the Constitution of May 3, 1791.[40]

Reforms of 1764-1766 improved the proceedings the sejm.[41] They introduced majority voting for items declared as "non crucial" (most economic and tax matters) and outlawed binding instructions from sejmiks.[41] Reforms of 1767 and 1773-1775 transferred some competences of the sejm to the commissions of elected delegates.[41] From 1768, hetmans were included among the senate members, and from 1775 also the Court Deputy Treasurer.[41]

In the senate there was no voting; after all the senators who wished had spoken on a given matter, the king or the chancellor formed a general opinion based on the majority.[35] Prior to the May 3 Constitution, in Poland the term "constitution" (Polish: konstytucja) had denoted all the legislation, of whatever character, that had been passed at a sejm.[42] Only with the adoption of the May 3 Constitution did konstytucja assume its modern sense of a fundamental document of governance.[43]

The Constitution of May 3, 1791 finally abolished the liberum veto, replacing it by majority voting, in most important matters requiring 75% of the votes.[27]

Location

-

Old Chamber of Deputies at the Royal Castle, Warsaw, 16th century

-

New Chamber of Deputies at the Royal Castle, Warsaw, late 17th century

-

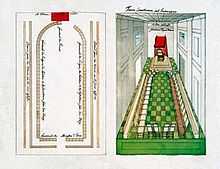

Seating arrangement in the Senate Chamber at the Royal Castle, Warsaw, during a regular sejm; and that chamber during the 1732 Convocation Sejm

-

Plan of the elective camp of Polish kings in Wola near Warsaw

Until the Union of Lublin (1569), sejms were held in Piotrków Trybunalski Castle, located in Piotrków, a town chosen for its proximity to the two major provinces of Poland, Greater Poland and Lesser Poland.[10][44][45] From 1493, other locations would also host the sejms, most prominently Kraków, where 29 sessions were held.[29][45] Other locations included Brest (1653), Bydgoszcz (1520), Jędrzejów (1576), Kamień (1573), Koło (1577), Korczyn (1511), Lublin (1506, 1554, 1566, 1569), Poznań (1513), Sandomierz (1500, 1519), Toruń (1519, 1577), and Warsaw (1556, 1563, and numerous times after 1568).[29]

After the Union, majority of the sejms where held at the Warsaw's Royal Castle.[46] A few were held elsewhere, particularly in the first years of the Commonwealth (see preceding list), and from 1673, every third sejm was to take place at Grodno in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (first hosted in the Old Hrodna Castle, later in the New Hrodna Castle).[26] In practice, most of the sejms were still held in Warsaw, which hosted 148 sejms, compared to 11 sejms hosted in Grodno.[45]

Sejms in Kraków were held in the Wawel Castle, within the Hall of the Deputies (Hall under the Heads) and the Senate Chamber.[45] The sejms in Warsaw were held in the Warsaw Castle, within the Chamber of Deputies (Hall of Three Pillars), with the upper Senate Chamber located literally above it.[45] In the late 17th century, new quarters were constructed for the Chamber of Deputies, and were joined on the same level by the senate quarters in the mid-18th century.[45] The new Senate Chamber was the larger of the two, as it was intended to host both chambers during the opening and closing ceremonies.[45]

Composition and electoral ordinance

Until 1468, sejms gathered only the high ranking nobility and officials, but the sejm of 1468 saw deputies elected from various local territories.[44] Although all nobles were allowed to participate in the general sejm, with the growing importance of local sejmiks in the 15th century, it became more common for the sejmiks to elect deputies for the general sejm.[10] In time, this shifted importance, particularly legislative competence, from local sejmiks to the general sejm.[47]

The sejm comprised two chambers, with varying numbers of deputies. After the 1569 Union of Lublin, the Kingdom of Poland was transformed into the federation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the numbers of sejm participants were significantly increased with the inclusion of the deputies from Lithuanian sejmiks.[46] The deputies had no set term of office, although in practice it was about four months long, from their election at a regional sejmik, to their report on the next sejmik dedicated to hearing and discussing the previous sejm's proceedings (those sejmiks were known as relational or debriefing).[25] Deputies had parliamentary immunity and any crimes against them were classified as lese-majesty.[25]

The two chambers were:

- A senat of high ecclesiastical and secular officials, forming the royal council. In the mid 15th century they numbered 73.[10] That number grew with time, with 81 senators around 1493-1504, and 95 around 1553-1565.[48] In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth the senate numbered over 140 bishops and other dignitaries;[26] it grew from 149 around 1598-1633 to 153 around 1764-1768, and 157 during the era of the Great Sejm (1788-1792).[48] The Constitution of May 3 set their number at 132.[27]

- A lower house, the sejm proper, of lower ranking officials and general nobility.[10] That number also grew with time, at first below that of the senators, with 53 deputies around 1493-1504, and 92 around 1553-1565.[48] In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the sejm chamber's number of deputies exceeded that of the senators.[48] After the Union of Lublin in 1569 it was composed of 170 deputies (Polish, singular: poseł, representing and elected by a local sejmik). The 170 included 48 from Lithuania.[49] Deputies from several cities and towns were allowed a status of observers.[49] The number of deputies grew to around 236 in the 1764-1768 period, dropping to 181 during the time of the Great Sejm (1788-1792).[48] The Constitution of May 3 set their number at 204, including 24 representatives from cities and towns.[27]

The Constitution of May 3 specified that the deputies were elected for two years, and did not require reelection in that period if any extraordinary sejms were to be called.[27] Senators for the most part were selected by the king from a number of candidates presented by the sejmiks.[27]

Usually larger voivodeships could send 6 deputies, smaller 2; ziemias, depending on their sizes, would sent 2 or 1.[49] Numbers of deputies elected to the sejm by sejmiks from particular localities, in the order of precedence, based on a 1569 decree, were as follows:[50][51]

Special sessions

In addition to the regular sessions of the general sejm, in the era of electable kings, beginning in 1573, three special types of sejms handled the process of the royal election in the interregnum period.[52] Those were:

- Convocation sejm (Sejm konwokacyjny). This sejm was called upon a death or abdication of a king by the Primate of Poland.[52] The deputies would focus on establishing the dates and any special rules for the election (in particular, preparation of pacta conventa, bills of nobility privileges to be sworn by the king), and screening the candidates.[52] This sejm was to last two weeks.[25]

- Election sejm (Sejm elekcyjny), during which the nobility voted for the candidate to the throne. This type of sejm was open to all members of the nobility who desired to attend it, and as such they often gathered much larger number of attendees than the regular sejms.[52][53] The exact numbers of attendees have never been recorded, and are estimated to vary from 10,000 to over 100,000; subsequently the voting could last for days (in 1573 it was recorded that it took four days).[54] To handle the increased numbers, those sejms would be held in Wola, then a village near Warsaw.[52] Royal candidates themselves were barred from attending this sejm, but were allowed to sent representatives.[54] This sejm was to last six weeks.[25]

- Coronation sejm (Sejm koronacyjny). This sejm was held in Kraków, where the coronation ceremony was traditionally held by the primate, who relinquished his powers to the chosen king.[55] This sejm was to last two weeks.[25]

Confederated sejm (Sejm skonfederowany) first appeared in 1573 (all convocation and election sejms were confederated), and became more popular in the 18th century as a counter to the disruption of liberum veto.[56] Seen as emergency or extraordinary sessions, they relied on majority voting to speed up the discussions and ensure a legislative outcome.[25][56] Many royal election sejms were confederated, as well as some of the normal sejm walny (general sejm) sessions.[52][56]

Jędruch, who classifies the regular general sejm session as ordinary, in addition to the convocation, election and coronation sessions, also distinguished the following additional types:

- Council of state

- Constitutional

- Delegation (ending with a formation of committees)

- Extraordinary

- General council (rada walna) without the king present. That sejm would be convoked by the primate when the king could not attend and had no legislative powers. It was attended by deputies from the preceding sejm. Held three times (in 1576, 1710 and 1734).

- General sejmik held instead of a sejm

- Inquest, debating the case of royal impeachment. Two such sejms were held (in 1592 and 1646).

- Pacification, to quell a potential civil war after a disputed election, to pacify the opponents through political concessions. Five such sejms were held (in 1598, 1673, 1698, 1699 and 1735).[4][25]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Norman Davies (2005). God's playground: a history of Poland in two volumes. Oxford University Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-19-925339-5. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Władysław Czapliński (1985). The Polish Parliament at the summit of its development (16-17th centuries): anthologies. Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. p. 13. ISBN 978-83-04-01861-7. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ↑ Norman Davies (30 March 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.20, 26-27

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.62-63

- ↑ Norman Davies (23 August 2001). Heart of Europe: The Past in Poland's Present. Oxford University Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-19-280126-5. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ Janusz Roszko (1980). Kolebka Siemowita. "Iskry". p. 170. ISBN 978-83-207-0090-9. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.63-64

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 10.9 10.10 10.11 10.12 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.104-106

- ↑ Jerzy Jan Lerski (1996). Historical dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 532. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Daniel Stone (2001). The Polish-Lithuanian state, 1386-1795. University of Washington Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Thomas Ertman (13 January 1997). Birth of the leviathan: building states and regimes in medieval and early modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-521-48427-5. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Jean W. Sedlar (April 1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. University of Washington Press. pp. 291–293. ISBN 978-0-295-97291-6. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ Zygmunt Gloger (1896). Słownik rzeczy starozytnych. Gebethner. p. 386. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ Samuel Orgelbrand (1866). Encyklopedyja powszechna. Orgelbrand. p. 193. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ Tadeusz Czacki; Kazimierz Józef Turowski (1861). O litewskich i polskich prawach, o ich duchu, źródlach, zwiazku, i o rzeczach zawartych w pierwszym Statucie dla Litwy, 1529 roku wydanym. Nakladem drukarni 'Czasu,'. p. 294. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ Oskar Halecki, W: F. Reddaway, J. H. Penson. The Cambridge History of Poland. CUP Archive. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-00-128802-4. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ F. W. Carter (20 April 2006). Trade And Urban Development in Poland: An Economic Geography of Cracow, from Its Origins to 1795. Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-521-02438-9. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ HALINA LERSKI (30 January 1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. ABC-CLIO. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-313-03456-5. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ Galeria Sztuki Polskiej (Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie) (1962). Malarstwo polskie od XVI do początku XX wieku: katalog. Muzeum. p. 103. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 173–174. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 25.6 25.7 25.8 25.9 25.10 25.11 25.12 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 125–132. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.219-220

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 27.7 27.8 27.9 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.310-312

- ↑ Przegląd humanistyczny. Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe. 2002. p. 24. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 427–431. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ Norman Davies (30 March 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.221-222

- ↑ Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Karol Rawer (1899). Dzieje ojczyste dla mlodziezy. p. 86. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ↑ Adam Zamoyski (15 April 2009). Poland: a history. Harper Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-00-728275-3. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.220-221

- ↑ Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ David J. Sturdy (2002). Fractured Europe, 1600–1721. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 236. ISBN 0-631-20513-6.

- ↑ Barbara Markiewicz, "Liberum veto albo o granicach społeczeństwa obywatelskiego" [w:] Obywatel: odrodzenie pojęcia, Warszawa 1993.

- ↑ Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.223

- ↑ George Sanford (2002). Democratic government in Poland: constitutional politics since 1989. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-333-77475-5. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.293-294

- ↑ "Konstytucja: Sejm laws passed by common consent. They had various characters: that of today's laws, and that of administrative acts. They pertained to national, local and special matters. They appeared with the date of the opening of the [Sejm] session.... They were published in the name of the monarch, were written in the Polish language, and with time appeared in print. Tax laws were published separately. A collection of constitutions was published in the 18th century by Stanisław Konarski under the title, Volumina legum [Volumes of Laws – the first collection of laws in Poland: Encyklopedia Polski, p. 301]." Encyklopedia Polski, pp. 306–7.

- ↑ This is implicit in the May 3rd Constitution's recognition as the world's second written national constitution, after the United States Constitution, in many sources, including Encyklopedia Polski (p. 307) and Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN, vol. 2, Warsaw, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1974, p. 543.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 45.5 45.6 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 90–100. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Paul R. Magocsi (1996). A history of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. p. 142. ISBN 0-8020-7820-6.

- ↑ Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.217-219

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.219

- ↑ Koneczny, Feliks (1924). Dzieje administracji w Polsce w zarysie (in Polish). Vilnius: Okręgowa Szkoła Policji Państwowej Ziemi Wileńskiej. ISBN 83-87809-20-9.

- ↑ Wojciech Kriegseisen (1991). Sejmiki Rzeczypospolitej szlacheckiej w XVII i XVIII wieku. Wydawn. Sejmowe. pp. 28–35. ISBN 978-83-7059-009-3. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 52.5 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.226

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||