Gender equality

Gender equality, also known as sex equality, gender egalitarianism, sexual equality or equality of the genders, is the view that men and women should receive equal treatment, and should not be discriminated against based on gender.[1] This is the objective of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which seeks to create equality in law and in social situations, such as in democratic activities and securing equal pay for equal work. To avoid complication, other genders (besides women and men) will not be treated in this Gender equality article. The related topic of rights is treated in two separate articles, Men's rights and Women's rights.

History

An early advocate for gender equality was Christine de Pizan, who in her 1405 book The Book of the City of Ladies wrote that the oppression of women is founded on irrational prejudice, pointing out numerous advances in society probably created by women.[2]

Shakers

As a group, the Shakers, an evangelical group which practiced segregation of the sexes and strict celibacy, were early practitioners of gender equality. They branched off from a Quaker community in the north-west of England before emigrating to America in 1774. In America, the head of the Shakers' central ministry in 1788, Joseph Meacham, had a revelation that the sexes should be equal, so he brought Lucy Wright into the ministry as his female counterpart, and together they restructured society to balance the rights of the sexes. Meacham and Wright established leadership teams where each elder, who dealt with the men's spiritual welfare, was partnered with an eldress, who did the same for women. Each deacon was partnered with a deaconess. Men had oversight of men; women had oversight of women. Women lived with women; men lived with men. In Shaker society, a woman did not have to be controlled or otherwise owned by any man. After Meacham's death in 1796, Wright was the head of the Shaker ministry until her own death in 1821. Going forward, Shakers maintained the same pattern of gender-balanced leadership for more than 200 years. They also promoted equality by working together with other women's rights advocates. In 1859, Shaker Elder Frederick Evans stated their beliefs forcefully, writing that Shakers were “the first to disenthrall woman from the condition of vassalage to which all other religious systems (more or less) consign her, and to secure to her those just and equal rights with man that, by her similarity to him in organization and faculties, both God and nature would seem to demand."[3] Evans and his counterpart, Eldress Antoinette Doolittle, joined women's rights advocates on speakers' platforms throughout the northeastern U.S. in the 1870s. A visitor to the Shakers wrote in 1875:

- “Each sex works in its own appropriate sphere of action, there being a proper subordination, deference and respect of the female to the male in his order, and of the male to the female in her order [emphasis added], so that in any of these communities the zealous advocates of ‘women’s rights’ may here find a practical realization of their ideal.”[4]

The Shakers were more than a radical religious sect on the fringes of American society; they put equality of the sexes into practice. They showed that equality could be achieved and how to do it.[5]

In the wider society, the movement towards gender equality began with the suffrage movement in Western cultures in the late-19th century, which sought to allow women to vote and hold elected office. This period also witnessed significant changes to women's property rights, particularly in relation to their marital status. (See for example, Married Women's Property Act 1882.)

Post-war era

After World War II, a more general movement for gender equality developed based on women's liberation and feminism. The central issue was that the rights of women should be the same as of men.

The United Nations and other international agencies have adopted several conventions, toward the promotion of gender equality. Prominent international instruments include:

- In 1960 the Convention against Discrimination in Education was adopted, coming into force in 1962 and 1968.

- The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) is an international treaty adopted in 1979 by the United Nations General Assembly. Described as an international bill of rights for women, it came into force on 3 September 1981.

- The Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, a human rights declaration adopted by consensus at the World Conference on Human Rights on 25 June 1993 in Vienna, Austria. Women's rights are addressed at para 18.[6]

- The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1993.

- In 1994, the twenty-year Cairo Programme of Action was adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo. This non binding programme-of-action asserted that governments have a responsibility to meet individuals' reproductive needs, rather than demographic targets. As such, it called for family planning, reproductive rights services, and strategies to promote gender equality and stop violence against women.

- Also in 1994, in the Americas, The Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women, known as the Convention of Belém do Pará, called for the end of violence and discrimination against women.[7]

- At the end of the Fourth World Conference on Women, the UN adopted the Beijing Declaration on 15 September 1995 - a resolution adopted to promulgate a set of principles concerning gender equality.

- The United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSRC 1325), which was adopted on 31 October 2000, deals with the rights and protection of women and girls during and after armed conflicts.

- The Maputo Protocol guarantees comprehensive rights to women, including the right to take part in the political process, to social and political equality with men, to control of their reproductive health, and an end to female genital mutilation. It was adopted by the African Union in the form of a protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, and came into force in 2005.

- The EU directive Directive 2002/73/EC - equal treatment of 23 September 2002 amending Council Directive 76/207/EEC on the implementation of the principle of equal treatment for men and women as regards access to employment, vocational training and promotion, and working conditions states that: "Harassment and sexual harassment within the meaning of this Directive shall be deemed to be discrimination on the grounds of sex and therefore prohibited."[8]

- The Council of Europe's Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, the first legally binding instrument in Europe in the field of violence against women,[9] came into force in 2014.

- The Council of Europe's Gender Equality Strategy 2014-2017, which has five strategic objectives:[10]

- Combating gender stereotypes and sexism

- Preventing and combating violence against women

- Guaranteeing Equal Access of Women to Justice

- Achieving balanced participation of women and men in political and public decision-making

- Achieving Gender Mainstreaming in all policies and measures

Such legislation and affirmative action policies have been critical to bringing about changes in societal attitudes. Most occupations are now equally available to men and women, in many countries. For example, many countries now permit women to serve in the armed forces, the police forces and to be fire fighters – occupations traditionally reserved for men. Although these continue to be male dominated occupations an increasing number of women are now active, especially in directive fields such as politics, and occupy high positions in business.

Similarly, men are increasingly working in occupations which in previous generations had been considered women's work, such as nursing, cleaning and child care. In domestic situations, the role of Parenting or child rearing is more commonly shared or not as widely considered to be an exclusively female role, so that women may be free to pursue a career after childbirth. For further information, see Shared earning/shared parenting marriage.

Another manifestation of the change in social attitudes is the non-automatic taking by a woman of her husband's surname on marriage.[11]

A highly contentious issue relating to gender equality is the role of women in religiously orientated societies. For example, the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam declared that women have equal dignity, but not equal rights, and this was accepted by many predominantly Muslim countries. In some Christian churches, the practice of churching of women may still have elements of ritual purification and the Ordination of women to the priesthood may be restricted or forbidden. Some Christians or Muslims believe in Complementarianism, a view that holds that men and women have different, but complementing roles. This view may be in opposition to the views and goals of gender equality.

In addition, there are also non-Western countries of low religiosity where the contention surrounding gender equality remains. In China, cultural preference for a male child has resulted in a shortfall of women in the population. The feminist movement in Japan has made many strides and has resulted in Rethe Gender Equality Bureau, but Japan still remains low in gender equality compared to other industrialized nations.

There are also countries that have a history of a high level of gender equality in certain areas of life, but not in other areas. An example is Finland, which has offered very high opportunities to women in public/professional life, but has had a weak legal approach to the issue of violence against women, with the situation in this country having been called a paradox.[12][13][14]

Not all ideas for gender equality have been popularly adopted. For example: topfreedom, the right to be bare breasted in public, frequently applies only to males and has remained a marginal issue. Breastfeeding in public is more commonly tolerated, especially in semi-private places such as restaurants.[15]

Underlying gender biases

There has been criticism from some feminists towards the political discourse and policies employed in order to achieve the above items of "progress" in gender equality, with critics arguing that these gender equality strategies are superficial, in that they do not seek to challenge social structures of male domination, and only aim at improving the situation of women within the societal framework of subordination of women to men. Sheila Jeffreys writes, "When women are encouraged to 'empower' themselves while leaving gendered power structures in place, the idea of empowerment could lead to blaming the women for their lack of progress".[16]

Indeed, it is the contentious meaning of the term "equality" itself that makes measuring gender equality "progress" inherently problematic. Newman and White suggest that equality can be understood in three distinct ways: identical treatment, differential treatment, and fair treatment.[17] Identical treatment is the claim that equality means the deployment of generalizing, abstract, content-less reason, unaffected with regard to the gender it addresses.[17] This view assumes that gender differences are entirely socially constructed concepts, and that an underlying, gender-neutral human should be the target of equality. Next, the differential treatment notion of equality is the claim that biological ("sex") differences do, in fact, exist as tangible and real, and that structuring treatment around these differences is not unequal, so long as these biological differences are accurately defined (that is to say, so long as differential treatment is not random).[17]

The third view, that equality is fair treatment, is in a sense a reaction to both of the previous two claims. Equality as identical treatment assumes that the criteria we use to define human nature is itself objective, neutral, and fair for each human, and differential treatment assumes that there are inherent, empirical, tangible, biological differences that the binary categories of male-female derive from. Theorists like Judith Lorber, Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, and many more attack both of these essentialist stances, articulating that any claim to an underlying human nature is absurd. In short, this is because what it is to be a human is at bottom a product of constructive discursive discourses. As Judith Lorber puts the point: "the paradox of 'human nature' is that it is always a manifestation of cultural meanings, social relationships, and power politics".[18] Furthermore, theorists like Catharine MacKinnon claim that all circulating articulations of this fictitious "universal human" actually reflect socially male biases.[18] That is to say, unadulterated, objective, pure reason is merely a tacit disguise for patriarchal reinforcement. It is clear, then, how the identical treatment model fails on this view. Similarly, by this logic, the differential treatment is shown to merely use male rationality to define and construct the gender difference - as a result, true equality is precluded.

This tacit inequality in our sexual concept poses a particular problem, because Western Liberal Democracies are premised on descriptions of people that describe them as equal, yet this exists alongside a description of women and men that describes them in terms that makes them unequal. So any claims that "Non-Western" countries are less gender equal than Western countries, for example, must not be too quickly accepted. Since this acceptance of inequality in sexes is perceived as a natural difference between men and women, it thus permeates into society relatively undiagnosed. Disguised as objective, the subjective/biased nature of these claims for equal treatment become particularly difficult to address. This allows the state/laws to appear to be gender-neutral and universally applicable, while ignoring the backdrop of the underlying forces that have structured our legal system and personal cognition in such a way as to promote equality of opportunity for social category male at the price of inequality for social category female. As Judith Lorber says: "it is the taken-for-grantedness of such everyday gendered behaviour that gives credence to the belief that the widespread differences in what women and men do must come from biology".[18] On such a view, then, addressing equality must take on more than formal equality, and become "fair treatment".[17] That is to say, the male paradigm cannot be seen as natural and objective, thus bias and preference and affirmative action to address past discriminations to women should be seen as furthering equality. Lorber describes the "bathroom problem" to articulate the inequality of overarching, gender-neutral laws.[17] She articulates how men's bathroom norms are used as the standard by which to determine how many and how large public bathrooms should be. For various reasons, however, women make more frequent use of the bathrooms than men, and as a result there are too few bathrooms for women, and sufficient amount for men. ). This tacit structural underpinning of male dominance is particularly dangerous for it creates the space for certain instances of female oppression to be viewed and experienced as the woman’s choice. For instance, a woman might choose not to pursue a job that is not compatible with her domestic obligations, while ignoring the structure of the patriarchal family in assigning those domestic roles to her, and furthermore the structuring of workplaces that tacitly stream out women that have this domestic duty in virtue of their strict required hours or inflexibility with days off, etc. As such, the fair treatment model of equality may correct the failure of purely formal/de jure gender equality to address such tacit structural and systematic inequality for women.[19]

A further criticism is that a focus on the situation of women in non-Western countries, while often ignoring the issues that exist in the West, is a form of imperialism and a way of reinforcing Western moral superiority; in fact, women in Western countries often face similar problems of domestic violence and rape as in other parts of the world;[20] and faced legal discrimination until just a few decades ago: for instance, in some Western countries such as Switzerland,[21] Greece,[22] Spain,[23] and France [24] women obtained equal rights in family law only in the 1980s. Another criticism is that there is a selective public discourse with regard to different types of oppression of women, with some forms of violence such as honor killings (most common in certain geographic regions such as parts of Asia and North Africa) being frequently the object of public debate, while other forms of violence, such as crimes of passion across Latin America where they are treated leniently,[25] do not receive the same attention in the West. In 2002, Widney Brown, advocacy director for Human Rights Watch, pointed out that "crimes of passion have a similar dynamic [to honor killings] in that the women are killed by male family members and the crimes are perceived [in those relevant parts of the world] as excusable or understandable".[25]

Efforts to fight inequality

World bodies have defined gender equality in terms of human rights, especially women's rights, and economic development.[26][27] UNICEF describes that gender equality "means that women and men, and girls and boys, enjoy the same rights, resources, opportunities and protections. It does not require that girls and boys, or women and men, be the same, or that they be treated exactly alike."[28]

The United Nations Population Fund has declared that men and women have a right to equality.[29] "Gender equity" is one of the goals of the United Nations Millennium Project, to end world poverty by 2015; the project claims, "Every single Goal is directly related to women's rights, and societies where women are not afforded equal rights as men can never achieve development in a sustainable manner."[27]

Thus, promoting gender equality is seen as an encouragement to greater economic prosperity.[26] For example, nations of the Arab world that deny equality of opportunity to women were warned in a 2008 United Nations-sponsored report that this disempowerment is a critical factor crippling these nations' return to the first rank of global leaders in commerce, learning and culture.[30] That is, Western bodies are less likely to conduct commerce with nations in the Middle East that retain culturally accepted attitudes towards the status and function of women in their society in an effort to force them to change their beliefs in the face of relatively underdeveloped economies.

In 2010, the European Union opened the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) in Vilnius, Lithuania to promote gender equality and to fight sex discrimination.

Gender equality is part of the national curriculum in Great Britain and many other European countries. Personal, Social and Health Education, religious studies and Language acquisition curricula tend to address gender equality issues as a very serious topic for discussion and analysis of its effect in society.

Violence against women

Violence against women (in short VAW) is a technical term used to collectively refer to violent acts that are primarily or exclusively committed against women. This type of violence is gender-based, meaning that the acts of violence are committed against women expressly because they are women, or as a result of patriarchal gender constructs. The UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women defines VAW as "any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life" and states that:[31]

- "violence against women is a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women, which have led to domination over and discrimination against women by men and to the prevention of the full advancement of women, and that violence against women is one of the crucial social mechanisms by which women are forced into a subordinate position compared with men"

Forms of VAW include sexual violence (including war rape, marital rape and child sexual abuse, the latter often in the context of child marriage), domestic violence, forced marriage, female genital mutilation, forced prostitution, sex trafficking, honor killings, dowry killings, acid attacks, stoning, flogging, forced sterilization, forced abortion, violence related to accusations of witchcraft, mistreatment of widows (e.g. widow inheritance). Fighting against VAW is considered a key issues for achieving gender equality. The Council of Europe adopted the Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Istanbul Convention).

In some parts of the world, various forms of VAW are tolerated and accepted as parts of everyday life; according to UNFPA:[32]

- "In some developing countries, practices that subjugate and harm women - such as wife-beating, killings in the name of honour, female genital mutilation/cutting and dowry deaths - are condoned as being part of the natural order of things."

In most countries, it is only in recent decades that VAW (in particular when committed in the family) has received significant legal attention. The Istanbul Convention acknowledges the long tradition of European countries of ignoring, de jure or de facto, this form of violence. In its explanatory report at para 219, it states:

- "There are many examples from past practice in Council of Europe member states that show that exceptions to the prosecution of such cases were made, either in law or in practice, if victim and perpetrator were, for example, married to each other or had been in a relationship. The most prominent example is rape within marriage, which for a long time had not been recognised as rape because of the relationship between victim and perpetrator."[33]

Reproductive and sexual health and rights

.jpg)

The importance of women having the right and possibility to have control over their body, reproduction decisions and sexuality, and the need for gender equality in order to achieve these goals are recognized as crucial by the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing and the UN International Conference on Population and Development Program of Action. The World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that promotion of gender equality is crucial in the fight against HIV/AIDS.[35]

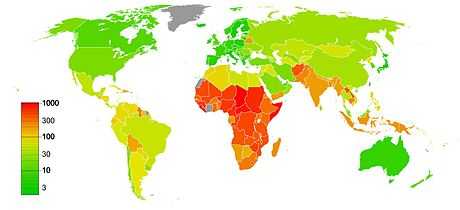

Maternal mortality is a major problem in many parts of the world. UNFPA states that countries have an obligation to protect women's right to health, but many countries do not do that.[36] Maternal mortality is considered today not just an issue of development, but also an issue of human rights.[36] According to UNFPA:[37]

- "Preventable maternal mortality occurs where there is a failure to give effect to the rights of women to health, equality and non-discrimination. Preventable maternal mortality also often represents a violation of a woman’s right to life."

The right to reproductive and sexual autonomy is denied to women in many parts of the world, through practices such as forced sterilization, forced/coerced sexual partnering (e.g. forced marriage, child marriage), criminalization of consensual sexual acts (such as sex outside marriage), lack of criminalization of marital rape, violence in regard to the choice of partner (honor killings as punishment for 'inappropriate' relations). Amnesty International’s Secretary General has stated that: "It is unbelievable that in the twenty-first century some countries are condoning child marriage and marital rape while others are outlawing abortion, sex outside marriage and same-sex sexual activity – even punishable by death."[38] All these practices infringe on the right of achieving reproductive and sexual health. High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay has called for full respect and recognition of women's autonomy and sexual and reproductive health rights, stating:[39]

- "Violations of women's human rights are often linked to their sexuality and reproductive role. Women are frequently treated as property, they are sold into marriage, into trafficking, into sexual slavery. Violence against women frequently takes the form of sexual violence. Victims of such violence are often accused of promiscuity and held responsible for their fate, while infertile women are rejected by husbands, families and communities. In many countries, married women may not refuse to have sexual relations with their husbands, and often have no say in whether they use contraception."

Adolescent girls are at the highest risk of sexual coercion, sexual ill health, and negative reproductive outcomes. The risks they face are higher than those of boys and men; this increased risk is partly due to gender inequity (different socialization of boys and girls, gender based violence, child marriage) and partly due to biological factors (females' risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections during unprotected sexual relations is two to four times that of males').[40]

Socialization within rigid gender constructs often creates an environment where sexual violence is common; according to the WHO: "Sexual violence is also more likely to occur where beliefs in male sexual entitlement are strong, where gender roles are more rigid, and in countries experiencing high rates of other types of violence."[41] The sexual health of women is often poor in societies where a woman's right to control her sexuality is not recognized. Richard A. Posner writes that "Traditionally, rape was the offense of depriving a father or husband of a valuable asset — his wife's chastity or his daughter's virginity".[42] Historically, rape was seen in many cultures (and is still seen today in some societies) as a crime against the honor of the family, rather than against the self-determination of the woman. As a result, victims of rape may face violence, in extreme cases even honor killings, at the hands of their family members.[43][44]

Freedom of movement

Women's freedom of movement continues to be legally restricted in some parts of the world. This restriction is often due to marriage laws. For instance, in Yemen, marriage regulations stipulate that a wife must obey her husband and must not leave home without his permission.[45] In some countries, women must legally be accompanied by their male guardians (such as the husband or male relative) when they leave home.[46]

The CEDAW states at Article 15 (4) that:[47]

- Article 15

- "4. States Parties shall accord to men and women the same rights with regard to the law relating to the movement of persons and the freedom to choose their residence and domicile."

Gendered arrangements of work and care

Since the 1950s, social scientists as well as feminists have increasingly criticized gendered arrangements of work and care and the male breadwinner role. Policies are increasingly targeting men as fathers as a tool of changing gender relations.[48]

Girls' access to education

In many parts of the world, girls' access to education is very restricted. Girls face many obstacles which prevent them to take part in education, including: early and forced marriages; early pregnancy; prejudice based on gender stereotypes at home, at school and in the community; violence on the way to school, or in and around schools; long distances to schools; vulnerability to the HIV epidemic; school fees, which often lead to parents sending only their sons to school; lack of gender sensitive approaches and materials in classrooms.[49][50][51] The United Nations Population Fund says:[52]

- "About two thirds of the world's illiterate adults are women. Lack of an education severely restricts a woman's access to information and opportunities. Conversely, increasing women's and girls' educational attainment benefits both individuals and future generations. Higher levels of women's education are strongly associated with lower infant mortality and lower fertility, as well as better outcomes for their children."

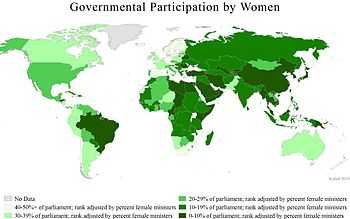

Political participation of women

Women are underrepresented in most countries' National Parliaments.[53] The 2011 UN General Assembly resolution on women’s political participation called for female participation in politics, and expressed concern about the fact that "women in every part of the world continue to be largely marginalized from the political sphere".[54] The Council of Europe states that:[55]

- "Pluralist democracy requires balanced participation of women and men in political and public decision-making. Council of Europe standards provide clear guidance on how to achieve this. "

Economic empowerment of women

Female economic activity is a common measure of gender equality in an economy. UN Women states that: "Investing in women’s economic empowerment sets a direct path towards gender equality, poverty eradication and inclusive economic growth."[56]

Gender discrimination often results in women ending in insecure, low-wage jobs, and being disproportionately affected by poverty, discrimination and exploitation.[56]

Marriage, divorce and property laws and regulations

Equal rights for women in marriage, divorce, and property/land ownership and inheritance are essential for gender equality. CEDAW has called for the end of discriminatory family laws.[57] In 2013, UNWomen stated that "While at least 115 countries recognize equal land rights for women and men, effective implementation remains a major challenge".[58]

The legal and social treatment of married women has been often discussed as a political issue from the 19th century onwards. John Stuart Mill, in The Subjection of Women (1869) compared marriage to slavery and wrote that: "The law of servitude in marriage is a monstrous contradiction to all the principles of the modern world, and to all the experience through which those principles have been slowly and painfully worked out."[59] In 1957, James Everett, then Minister for Justice in Ireland, stated: "The progress of organised society is judged by the status occupied by married women".[60]

Laws regulating marriage and divorce continue to discriminate against women in many countries. For example, in Yemen, marriage regulations state that a wife must obey her husband and must not leave home without his permission.[45] In Iraq husbands have a legal right to "punish" their wives. The criminal code states at Paragraph 41 that there is no crime if an act is committed while exercising a legal right; examples of legal rights include: "The punishment of a wife by her husband, the disciplining by parents and teachers of children under their authority within certain limits prescribed by law or by custom".[61] In the 1990s and the 21st century there has been progress in many countries in Africa: for instance in Namibia the marital power of the husband was abolished in 1996 by the Married Persons Equality Act; in Botswana it was abolished in 2004 by the Abolition of Marital Power Act; and in Lesotho it was abolished in 2006 by the Married Persons Equality Act.[62]

Violence and mistreatment of women in relation to marriage has come to international attention during the past decades. This includes both violence committed inside marriage (domestic violence) as well as violence related to marriage customs and traditions (such as dowry, bride price, forced marriage and child marriage). Violence against a wife continues to be seen as legally acceptable in some countries; for instance in 2010, the United Arab Emirates's Supreme Court ruled that a man has the right to physically discipline his wife and children as long as he does not leave physical marks.[63] The criminalization of adultery has been criticized as being a prohibition, which, in law or in practice, is used primarily against women; and incites violence against women (crimes of passion, honor killings). A Joint Statement by the United Nations Working Group on discrimination against women in law and in practice in 2012 stated:[64] "the United Nations Working Group on discrimination against women in law and in practice is deeply concerned at the criminalization and penalization of adultery whose enforcement leads to discrimination and violence against women." UN Women also stated that "Drafters should repeal any criminal offenses related to adultery or extramarital sex between consenting adults".[65]

Investigation and prosecution of crimes against women and girls

Human rights organizations have expressed concern about the legal impunity of perpetrators of crimes against women, with such crimes being often ignored by authorities.[66] This is especially the case with murders of women in Latin America.[67][68][69] In particular, there is impunity in regard to domestic violence. High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, has stated on domestic violence against women:[70]

- "The reality for most victims, including victims of honor killings, is that state institutions fail them and that most perpetrators of domestic violence can rely on a culture of impunity for the acts they commit – acts which would often be considered as crimes, and be punished as such, if they were committed against strangers."

Women are often, in law or in practice, unable to access legal institutions. UNWomen has said that, "Too often, justice institutions, including the police and the courts, deny women justice".[71]

Harmful traditional practices

"Harmful traditional practices" refer to forms of violence which are committed in certain communities often enough to become cultural practice, and accepted for that reason. Young women are the main victims of such acts, although men can be affected.[73] They occur in an environment where women and girls have unequal rights and opportunities.[74] These practices include, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights:[74]

- "female genital mutilation (FGM); forced feeding of women; early marriage; the various taboos or practices which prevent women from controlling their own fertility; nutritional taboos and traditional birth practices; son preference and its implications for the status of the girl child; female infanticide; early pregnancy; and dowry price"

Female genital mutilation is defined as "procedures that intentionally alter or cause injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons".[75] The practice is concentrated in 29 countries in Africa and the Middle East, and it often has serious negative health consequences.[75] It is most commonly carried out on girls between infancy and 15 years old.[73]

Son preference refers to a cultural preference for sons over daughters, and manifests itself through practices such as sex selective abortion; female infanticide; or abandonment, neglect or abuse of girl-children.[74]

Early marriage, child marriage or forced marriage is prevalent in parts of Asia and Africa. The majority of victims seeking advice are female and aged between 18 and 23;[73] it can have harmful effects on a girl's education and development, and may expose girls to social isolation or abuse.[74][76][77]

Abuses regarding nutrition are taboos in regard to certain foods, which result in poor nutrition of women, and may endanger their health, especially if pregnant.[74]

Women's ability to control their fertility is often reduced. For instance, in northern Ghana, the payment of bride price signifies a woman's requirement to bear children, and women using birth control face threats, violence and reprisals.[78] Births in parts of Africa are often attended by traditional birth attendants (TBAs), who sometimes perform rituals that are dangerous to the health of the mother. In many societies, a difficult labour is believed to be a divine punishment for marital infidelity, and such women face abuse and are pressured to "confess" to the infidelity.[74]

Tribal traditions can be harmful to males; for instance, the Satere-Mawe tribe use bullet ants as an initiation rite. Men must wear gloves with hundreds of bullet ants woven in for ten minutes: the ants' stings cause severe pain and paralysis. This experience must be completed twenty times for boys to be considered "warriors".[79]

Other harmful traditional practices include marriage by abduction, ritualized sexual slavery (Devadasi, Trokosi), breast ironing and widow inheritance.[80][81][82][83]

Portrayal of women in the media

The way women are represented in the media has been criticized as interfering with the aim of achieving gender equality by perpetuating negative gender stereotypes. The exploitation of women in mass media refers to the criticisms that are levied against the use or portrayal of women in the mass media, when such use or portrayal aims at increasing the appeal of media or a product, to the detriment of, or without regard to, the interests of the women portrayed, or women in general. Concerns include the fact that the media has the power to shape the population's perceptions and to influence ideas, and therefore the sexist portrayals of women in the media may impact on how society sees and treats women in real life.[84] One common criticism of the way women are represented in the media is that the media reinforces stereotypical societal views of "what women are for", by portraying women either as submissive housewives or as sex objects.[85]

Health

Social constructs of gender (that is, cultural ideals of socially acceptable masculinity and femininity) often have a negative effect on health. The WHO cites the example of women not being allowed to travel alone outside the home (to go to the hospital), and women being prevented by cultural norms to ask their husbands to use a condom, in cultures which simultaneously encourage male promiscuity, as social norms that harm women's health. Teenage boys suffering accidents due to social expectations of impressing their peers through risk taking, and men dying at much higher rate from lung cancer due to smoking, in cultures which link smoking to masculinity, are cited by the WHO as examples of gender norms negatively affecting men's health.[86] The WHO has also stated that there is a strong connection between gender socialization and transmission and lack of adequate management of HIV/AIDS.[35]

Gender mainstreaming

Gender mainstreaming is the public policy of assessing the different implications for women and men of any planned policy action, including legislation and programmes, in all areas and levels, with the aim of achieving gender equality.[87][88] The concept of gender mainstreaming was first proposed at the 1985 Third World Conference on Women in Nairobi, Kenya. The idea has been developed in the United Nations development community.[89] Gender mainstreaming "involves ensuring that gender perspectives and attention to the goal of gender equality are central to all activities".[90]

According to the Council of Europe definition: "Gender mainstreaming is the (re)organisation, improvement, development and evaluation of policy processes, so that a gender equality perspective is incorporated in all policies at all levels and at all stages, by the actors normally involved in policy-making."[55]

See also

General issues

- Special Measures for Gender Equality in The United Nations(UN)

- Complementarianism

- Egalitarianism

- Feminism

- Gender inequality

- Gender mainstreaming

- Masculism

- Men's rights

- Right to equal protection

- Sex and gender distinction

- Sexism

- Women's rights

Specific issues

- Bahá'í Faith and gender equality

- Female economic activity

- Female education

- Gender Parity Index (in education)

- Gender polarization

- Gender sensitization

- Matriarchy

- Matriname

- Mixed-sex education

- Patriarchy

- Quaker Testimony of Equality

- Shared Earning/Shared Parenting Marriage (also known as Peer Marriage)

- Women in Islam

Laws

- Anti-discrimination law

- Danish Act of Succession referendum, 2009

- Equal Pay Act of 1963 (United States)

- Equality Act 2006 (UK)

- Equality Act 2010 (UK)

- European charter for equality of women and men in local life

- Gender Equality Duty in Scotland

- Gender Equity Education Act (Taiwan)

- Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act (United States, 2009)

- List of gender equality lawsuits

- Paycheck Fairness Act (in the US)

- Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (United States)

- Uniform civil code (India)

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325

- Women's Petition to the National Assembly (France, 1789)

Organizations and ministries

- Afghan Ministry of Women Affairs (Afghanistan)

- Center for Development and Population Activities (CEDPA)

- Christians for Biblical Equality

- Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality (European Parliament)

- Equal Opportunities Commission (UK)

- Gender Empowerment Measure, a metric used by the United Nations

- Gender-related Development Index, a metric used by the United Nations

- Government Equalities Office (UK)

- International Center for Research on Women

- International Society for Peace

- Ministry of Integration and Gender Equality (Sweden)

- Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development (Malaysia)

- Philippine Commission on Women (Philippines)

- The Girl Effect, an organization to help girls, worldwide, toward ending poverty

Historical anecdotal reports

Other related topics

- Global Gender Gap Report

- International Men's Day

- Potty parity

- Women's Equality Day

- Illustrators for Gender Equality

- Gender apartheid

References

- ↑ United Nations. Report of the Economic and Social Council for 1997. A/52/3.18 September 1997, at 28: "Mainstreaming a gender perspective is the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies or programmes, in all areas and at all levels. It is a strategy for making women's as well as men's concerns and experiences an integral dimension of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programmes in all political, economic and societal spheres so that women and men benefit equally and inequality is not perpetuated. The ultimate goal is to achieve gender equality."

- ↑ Riane Eisler (2007). The Real Wealth of Nations: Creating a Caring Economics. p. 72.

- ↑ Frederick William Evans. Shakers: Compendium of the Origin, History, Principles, Rules and Regulations, Government, and Doctrines of the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing : with Biographies of Ann Lee, William Lee, Jas. Whittaker, J. Hocknell, J. Meacham, and Lucy Wright. Appleton; 1859. p. 34. Note, this is an online Google book.

- ↑ Glendyne R. Wergland, Sisters in the Faith: Shaker Women and Equality of the Sexes (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011).

- ↑ Wendy R. Benningfield, Appeal of the Sisterhood: The Shakers and the Woman’s Rights Movement (University of Kentucky Lexington doctoral dissertation, 2004), p. 73.

- ↑ http://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?page=topic&tocid=459d17822&toid=459b17a82&docid=3ae6b39ec&skip=O

- ↑ http://www.oas.org/en/mesecvi/convention.asp

- ↑ http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:1976L0207:20021005:EN:PDF

- ↑ https://www.oas.org/es/mesecvi/docs/CSW-SideEvent2014-Flyer-EN.pdf

- ↑ https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?id=2105977&Site=COE&BackColorInternet=C3C3C3&BackColorIntranet=EDB021&BackColorLogged=F5D383

- ↑ http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-29804450

- ↑ http://www.academia.edu/992154/The_Paradoxical_Approach_to_Intimate_Partner_Violence_in_Finland

- ↑ http://www.scottishaffairs.org/backiss/pdfs/sa48/sa48_McKie_and_Hearn.pdf

- ↑ According to a report by Amnesty International: "Finland is repeatedly reminded of its widespread problem of violence against women and recommended to take more efficient measures to deal with the situation. International criticism concentrates on the lack of measures to combat violence against women in general and in particular on the lack of a national action plan to combat such violence and on the lack of legislation on domestic violence. (...) Compared with Sweden, Finland has been slower to reform legislation on violence against women. In Sweden, domestic violence was already illegal in 1864, while in Finland such violence was not outlawed until 1970, over a hundred years later. In Sweden the punishment of victims of incest was abolished in 1937, but not until 1971 in Finland. Rape within marriage was criminalized in Sweden in 1962, but the equivalent Finnish legislation only came into force in 1994 – making Finland one of the last European countries to criminalize marital rape. In addition, assaults taking place on private property did not become impeachable offenses in Finland until 1995. Only in 1997 did victims of sexual offenses and domestic violence in Finland become entitled to government-funded counseling and support services for the duration of their court cases." (pp. 89–91) – Case Closed – Rape and human rights in the Nordic countries

- ↑ Jordan, Tim (2002). Social Change (Sociology and society). Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-23311-3.

- ↑ Man's Dominion: The Rise of Religion and the Eclipse of Women's Rightsby Sheila Jeffreys, pg 94

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Newman, Jacquetta A., and Linda A. White (2012). Women, Politics, and Public Policy: The Political Struggles of Canadian Women. Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford UP; pp.14-15.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Lorber, Judith (2011). Ch.3 "Seeing Is Believing: Biology as Ideology," pp. 11-18 in The Gendered Society Reader, Ed. Michael S. Kimmel and Amy Aronson. New York: Oxford University Press; pp. 14-17.

- ↑ Newman and White 2012, pp. 14-16.

- ↑ An Introduction to Feminist Philosophy, by Alison Stone, pp. 209-211

- ↑ In 1985, a referendum guaranteed women legal equality with men within marriage. The new reforms came into force in January 1988.Women's movements of the world: an international directory and reference guide, edited by Sally Shreir, p. 254

- ↑ In 1983, legislation was passed guaranteeing equality between spouses, abolishing dowry, and ending legal discrimination against illegitimate children Demos, Vasilikie. (2007) “The Intersection of Gender, Class and Nationality and the Agency of Kytherian Greek Women.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association. August 11.

- ↑ In 1981, Spain abolished the requirement that married women must have their husbands’ permission to initiate judicial proceedings

- ↑ Although married women in France obtained the right to work without their husbands' permission in 1965, and the paternal authority of a man over his family was ended in 1970 (before that parental responsibilities belonged solely to the father who made all legal decisions concerning the children), it was only in 1985 that a legal reform abolished the stipulation that the husband had the sole power to administer the children's property.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2002/02/0212_020212_honorkilling.html

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 World Bank (September 2006). "Gender Equality as Smart Economics: A World Bank Group Gender Action Plan (Fiscal years 2007–10)" (PDF).

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 United Nations Millennium Campaign (2008). "Goal #3 Gender Equity". United Nations Millennium Campaign. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- ↑ UNICEF. "Promoting Gender Equality: An Equity-based Approach to Programming" (PDF). UNICEF. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- ↑ UNFPA (February 2006). "Gender Equality: An End in Itself and a Cornerstone of Development". United Nations Population Fund. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- ↑ Gender equality in Arab world critical for progress and prosperity, UN report warns, E-joussour (21 October 2008)

- ↑ http://www.un-documents.net/a48r104.htm

- ↑ http://www.unfpa.org/gender/practices.htm

- ↑ http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/EN/Reports/Html/210.htm

- ↑ Country Comparison: Maternal Mortality Rate in The CIA World Factbook.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 http://www.who.int/gender/hiv_aids/en/

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/reducing_mm.pdf

- ↑ http://www.unfpa.org/public/publications/pid/4968

- ↑ https://www.amnesty.org/en/news/sexual-and-reproductive-rights-under-threat-worldwide-2014-03-06

- ↑ http://www.chr.up.ac.za/images/files/news/news_2012/Navi%20Pillay%20Lecture%2015%20May%202012.pdf

- ↑ http://www.unfpa.org/resources/giving-special-attention-girls-and-adolescents

- ↑ http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/summary_en.pdf

- ↑ Sex and Reason, by Richard A. Posner, page 94.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/honourcrimes/crimesofhonour_1.shtml

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-13760895

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrc/docs/ngos/Yemen%27s%20darkside-discrimination_Yemen_HRC101.pdf

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/24691034

- ↑ http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/text/econvention.htm

- ↑ Bjørnholt, M. (2014). "Changing men, changing times; fathers and sons from an experimental gender equality study" (PDF). The Sociological Review 62 (2): 295–315. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12156.

- ↑ http://www.teachers.org.uk/node/12978

- ↑ http://www.campaignforeducationusa.org/obstacles-to-education-for-girls-and-women

- ↑ http://plan-international.org/files/Africa/progress-and-obstacles-to-girls-education-in-africa

- ↑ "Gender equality". United Nations Population Fund. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ↑ http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm

- ↑ http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/66/130

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/standardsetting/equality/02_GenderEqualityProgramme/Council%20of%20Europe%20Gender%20Equality%20Strategy%202014-2017.pdf

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 http://www.unwomen.org/ru/what-we-do/economic-empowerment

- ↑ http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/Equalityinfamilyrelationsrecognizingwomensrightstoproperty.aspx

- ↑ http://www.unwomen.org/lo/news/stories/2013/11/womens-land-rights-are-human-rights-says-new-un-report

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mill-john-stuart/1869/subjection-women/ch04.htm

- ↑ http://historical-debates.oireachtas.ie/S/0047/S.0047.195701160007.html

- ↑ http://law.case.edu/saddamtrial/documents/Iraqi_Penal_Code_1969.pdf

- ↑ http://www.nyulawglobal.org/globalex/lesotho.htm

- ↑ http://edition.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/meast/10/19/uae.court.ruling/index.html?_s=PM:WORLD

- ↑ http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=12672&

- ↑ http://www.endvawnow.org/en/articles/738-decriminalization-of-adultery-and-defenses.html%29

- ↑ http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/ImpunityForVAWGlobalConcern.aspx

- ↑ http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cedaw/docs/ngos/CDDandCMDPDH_forthesession_Mexico_CEDAW52.pdf

- ↑ http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2013/4/femicide-in-latin-america

- ↑ http://cgrs.uchastings.edu/our-work/central-america-femicides-and-gender-based-violence

- ↑ http://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=9869&LangID=E

- ↑ http://progress.unwomen.org/

- ↑ "Prevalence of FGM/C". UNICEF. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 http://www.gbv.scot.nhs.uk/gbv/harmful-traditional-practices

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 74.4 74.5 http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FactSheet23en.pdf

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/

- ↑ http://www.unicef.org/protection/57929_58008.html

- ↑ http://www.hrw.org/topic/womens-rights/child-marriage

- ↑ http://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/councilarticles/sfp/SFP301Bawah.pdf

- ↑ Backshall, Steve (6 January 2008). "Bitten by the Amazon". London: The Sunday Times. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ http://www.krepublishers.com/02-Journals/T-Anth/Anth-13-0-000-11-Web/Anth-13-2-000-11-Abst-Pdf/Anth-13-2-121-11-720-Wadesango-N/Anth-13-2-121-11-720-Wadesango-N-Tt.pdf

- ↑ http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/egm/elim-disc-viol-girlchild/ExpertPapers/EP.4%20%20%20Raswork.pdf

- ↑ http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CEDAW/HarmfulPractices/GenderEmpowermentandDevelopment.pdf

- ↑ http://www.kit.nl/net/KIT_Publicaties_output/ShowFile2.aspx?e=1415

- ↑ http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/standardsetting/equality/03themes/women_media/Media%20and%20the%20Image%20of%20Women,%20Amsterdam%202013%20-%20Abridged%20Report.pdf

- ↑ http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2013/474442/IPOL-FEMM_ET%282013%29474442_EN.pdf

- ↑ http://www.who.int/gender/genderandhealth/en/

- ↑ Booth, C. and Bennett, (2002) ‘Gender Mainstreaming in the European Union’, European Journal of Women’s Studies 9 (4): 430–46.

- ↑ http://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/gender/newsite2002/about/defin.htm

- ↑ "II. The Origins of Gender Mainstreaming in the EU", Academy of European Law online

- ↑ http://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/gendermainstreaming.htm

External links

- United Nations Rule of Law: Gender Equality, on the relationship between gender equality, the rule of law and the United Nations.

- HillarysVillage, Forum for women, minorities, members of the gay community and those who are otherwise marginalized.

- The OneWorld Guide to Gender Equality

- WomenWatch, the United Nations Internet Gateway on Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women

- Women's Empowerment, the United Nations Development Program's Gender Team

- GENDERNET, International forum of gender experts working in support of gender equality. Development Co-operation Directorate of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- Gender at the OECD Development Centre, gender activities at the OECD Development Centre

- Gender Equality as Smart Economics World Bank

- Women Leadership: Yes she can!

- The Local Gender equality in Sweden (news collection)

- Women Can Do It!

- Return2WorkMums For women returners to the workplace

- Sexism Discussion Group

- Sexual Equality and Romantic Love

- Gender Equality Tracker

- Gender and Work Database

- Gender and the Built Environment Database

- WiTEC – The European Association for Women in Science, Engineering and Technology (SET)

- Gender Equality in Labour & Life – Online Course focus on PA (SET)

- National Center for Transgender Equality

- Egalitarian Jewish Services A Discussion Paper

| Library resources about Gender equality |