Gebel el-Arak Knife

|

The Gebel el-Arak knife, on display at the Musée du Louvre. | |

| Material | Elephant ivory, flint |

|---|---|

| Size | 25.8 centimetres (10.2 in) |

| Created | Naqada II d from c. 3450 BC[1] |

| Discovered | Bought by Georges Aaron Bénédite in Cairo from antique dealer M. Nahman, February 1914 |

| Present location | Musée du Louvre, Sully wing, room 20 |

| Identification | E 11517 |

The Gebel el-Arak Knife is an ivory and flint knife dating from the Naqada II d period of Egyptian prehistory, starting circa 3450 BC. The knife was purchased in 1914 in Cairo by Georges Aaron Bénédite for the Louvre, where it is now on display in the Sully wing, room 20.[2] At the time of its purchase, the knife handle was said by the seller to have been found at the site of Gebel el-Arak but it is today believed to come from Abydos.

Purchase and origin

Purchase

The Gebel el-Arak knife was bought for the Louvre by the philologist and egyptologist Georges Aaron Bénédite in February 1914 from a private antique dealer, M. Nahman, in Cairo.[1] Bénédite immediately recognized the extraordinary state of preservation of the artefact as well as its archaic date. On March the 16th, 1914, he wrote to Charles Boreux, then head of the département des Antiquités égyptiennes of the Louvre about the knife the unsuspecting antique dealer presented him:

[...] an archaic flint knife with an ivory handle of the greatest beauty. This is the masterpiece of predynastic sculpture [...] executed with remarkable finesse and elegance. This is a work of great detail [...] and the interest of what is represented is even beyond the artistic value of the artefact. On one side is a hunting scene; on the other a scene of war or raid. At the top of the hunting scene [...] the hunter wears a large Chaldean garment: he head is covered by a hat like that of our Gudea [...] and he grasps two lions standing against him. You can judge the importance of this asiatic representation [...] we will own one of the most important prehistoric monuments, if not more. It is, in definitive, in tangible and resumed form, the first chapter of the history of Egypt (emphasis in the original).[1][3]

At the time when the knife was bought, its blade and handle were separated as the seller did not realize that both fitted together.[4] Later on, C. Boreux proposed that be knife be restored and that the blade and handle be put together. These operations were performed in March 1933 by Léon André who worked mainly on consolidating the ensemble and treated the ivory of the handle for its conservation.[5] The last restoration of the knife was carried out in 1997 by Agnès Cascio and Juliette Lévy.[1]

Origin

At the time of its purchase by G. Bénédite, the knife handle was said by the antique dealer to have been found at the site of Gebel el-Arak (جبل العركى), a plateau near the village of Nag Hammadi, 40 kilometres (25 mi) south of Abydos. However the true origin of the knife is given by G. Bénédite in his letter to C. Boreux. He writes:

[...] the seller did not suspect that the flint [blade] belonged with the handle and presented it to me as witness of the recent finds from Abydos.[1]

That the knife indeed originates from Abydos is supported by the otherwise total absence of archaeological finds from Gebel el-Arak, while intense excavations by Émile Amélineau, Flinders Petrie, Édouard Naville and Thomas Eric Peet were taking place at the time of the purchase at the Umm el-Qa'ab, the necropolis of predynastic and early dynastic rulers in Abydos.

Description

Blade

The blade of the knife is made of homogenous finely grained yellowish flint, a type of Egyptian flint called chert. Flint is widely available in Egypt from Cairo to Esna but the blades of ceremonial flint knives were exclusively made of caramel colored chert, perhaps because this color resembles that of metal.[6] The blade was produced from the original stone in five steps:[1][7]

|

|

| Gebel el-Arak knife, ripple-flaked side of the blade | Gebel el-Arak knife, polished side of the blade |

- Roughing of the original stone.

- Preformation of the blade by percussion flaking.

- Polishing of both sides of the blade. This operation is required before the ripple-flaking, see below. One side of the blade was left polished and did not receive further work, thus showing a smooth ground surface, maybe to imitate a metal blade.[1]

- Ripple-flaking on one side of the blade. This consists in uniformly removing long and thin strips of stone with parallel pressure flaking, creating a regular pattern of S undulations on the surface of the stone. Analysis of the shock waves on the surface of the blade reveals they were produced from the top to the bottom of the blade and from left to right, in a counterclockwise fashion. This work was probably made with pointed copper tools. The ripple-flaking of this side of the blade has no incidence on its sharpness, indicating that it may have served an artistic purpose.

- Fine serration of the edge of the blade by micro-flaking. This step produces the sharpness of the blade.

The blade of the Gebel el-Arak knife as well as of other ripple-flake knives of the same period are considered the high point of the silex tool making techniques.[1][8] Specialists of the Predynastic period of Egypt, such as Béatrix Midant-Reynes, argue that the quality and amount of work required for the creation of the blade goes beyond what is required for a functional knife. Thus the purpose and value of the knife would be artistic, the blade being a demonstration of technical skills aiming at the beauty of the result.[9] This hypothesis is strengthened by a detailed use-wear analysis of the blade which showed that the knife has never been used.[10]

The blade weights 92.3 grams, its precise dimensions are as follows:

| Total length: | 18.8 centimetres (7.4 in) |

| Width of the blade at its center: | 5.7 centimetres (2.2 in) |

| Thickness of the blade at its center: | 0.6 centimetres (0.24 in) |

| Length of blade inside the handle: | 2.8 centimetres (1.1 in) |

| Width of the blade inside the handle: | 3.7 centimetres (1.5 in) |

Handle

|

|

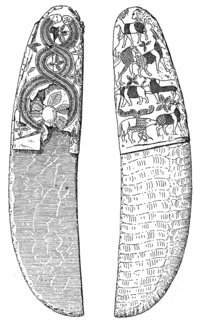

| Gebel el-Arak knife, back side of the handle | Gebel el-Arak knife, front side of the handle |

The handle is made of the ivory of an elephant tusk, and not from a hippopotamus canine tooth as was first thought.[1][11][12] The handle was carved along the axis of the tusk, as evidenced by a dark spot located above the head of the "Master of the beasts", which is the tip of pulp cavity of the tusk.[1] Once extracted from the tusk, the handle was polished on both sides and hollowed out to receive the blade. The thickness of the handle around the tang of the blade varies from 2 to 3 millimetres (0.12 in), which explains that the ivory is cracked there, with some pieces lost. At the bottom of the handle, the edge was beveled, and probably received a crimp of precious metal that would have reinforced the assemblage of the handle with the blade. At the time of the purchase, Bénédite reported that he could see traces of gold leaf on the bottom of the handle, now gone.[1] The assemblage supports the hypothesis that the knife was not functional: the tang of the blade is too short and the handle too thin for the knife to have been practical.[1]

The handle is richly carved in low relief with a scene of a battle on the side that would have faced a right-handed user and with mythological themes on the other side. This side has a knob in its center through which a strap could be passed. Just as for the blade, a use-wear analysis of the knob demonstrated that it has never been used. The carvings were executed on the polished surface of the tusk with a silex microburin from top to bottom, one register after the other. The artisan first carved the main figures and then carved the places where the figures meet, such as the arms of the combatants. The depth of the carvings does not exceed 2 millimetres (0.079 in).[1]

The precise dimensions of the handle are as follows:

| Total length: | 9.5 centimetres (3.7 in) |

| Width of the basis: | 4.2 centimetres (1.7 in) |

| Average thickness: | 1.2 centimetres (0.47 in) |

| Length of the knob: | 2.0 centimetres (0.79 in) |

| Width of the knob: | 1.3 centimetres (0.51 in) |

| Thickness of the knob: | 1.0 centimetre (0.39 in) |

Reliefs

The handle of the knife is carved on both sides with finely executed figures organized in five horizontal registers. The opposite side of the handle shows Mesopotamian influence[13] featuring a figure wearing Mesopotamian clothing flanked by two upright lions symbolizing the Morning and Evening Stars (now both identified with the planet Venus). Robert du Mesnil du Buisson said the central figure is the god El.[14] David M. Rohl identifies him with Meskiagkasher (Biblical Cush),[15] who "journeyed upon the sea and came ashore at the mountains".[16]Nicolas Grimal refrains from speculating on the identity of the ambiguous figure, referring to it as a "warrior".[17] This side of the handle also contains a "knob", a perforated suspension lug that would have supported the knife handle, keeping it level while resting on a level surface and also could have been used to thread a cord to hang it from the body as an ornament.

Similar knives

Today a total of 17 similar ceremonial knives with decorated handles are known.[1][18][19] These knives comprise:

- The ritual knife of the Brooklyn Museum, discovered by Jacques de Morgan in the Tomb 32 at Abu Zeidan near Edfu, and similar in size to the Gebel el-Arak knife. The handle of the knife, made of elephant ivory, is decorated with 227 animals carved in 10 registers on both faces.[20] The figures are tighly packed and entirely cover the handle. They represent real animals, all depicted at approximatively the same size and organized in processions by species: elephants (some walking on snakes), storks, lions, oryxes and bovids. Other less common animals interrupt the processions: a giraffe, a heron, a bustard and a dog chasing after an oryx. Finally, two electric cat fishes are represented on the outer margin of the handle. The only non-animal figure is a rosette, a royal symbol of mesopotamian origin found on Egyptian artifacts of the predynastic period and until the 1st dynasty, such as the Scorpion Macehead and Narmer palette.[1] The decoration of the handle is very similar to that of a predynastic hair comb, on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[21]

- The Pitt-Rivers knife bought in the mid 19th century by Reverend G. Chester from an antique dealer who reported finding it in Sheikh Hamada, near Sohag in Upper Egypt. The knife dates back to the late predynastic period, from ca. 3300 BC to 3100 BC,[22] and is now on display at the British Museum’s Early Egypt gallery, room 64, under the catalog number EA 68512.[23] The blade of the knife is virtually identical in style to that of the Gebel el-Arak knife, although slightly larger.[1] The iconography of the handle is similar to that of the ritual knife, comprising six rows of wild animals carved in raised relief. The animals include elephants walking on snakes, storks, a heron, lions followed by a dog, short and long-horned cattle, perhaps jackals, an ibis, a deer, hartebeests, oryxes and a barbary sheep.[24] Similar motifs are found on pottery and clay seals from funerary contexts of the predynastic and early dynastic periods, most notably in Abydos.[1][25]

- The Gebel-Tarif knife dating to the Naqada III period.[26] On one side, the handle of the knife shows two snakes encircling rosettes. The other side is organized in four rows. The top and second rows depict scenes of predation with a leopard and a lion attacking ibexes. Beneath these is a domesticated heavy hunting dog wearing a collar pursued by a lion or another dog.[27] Finally the bottom row represents a griffin and an ibex[27] The knife is now in the Egyptian Museum under the catalog number CG 14265.

Two worn and battered knives can be found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art[28] and at the National Archaeological Museum (France).

The perfect similarity between the blades of these knives and that of the Gebel el-Arak led scholar Diane L. Holmes to propose that the knives were all produced by a small number of workshops in one area and may be the product of a few craftsmen who practised this extremely specialized skill over a period of a few generations [29]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 Élisabeth Delange: Le poignard égyptien dit "du Gebel el-Arak", Musée du Louvre éditions, Collection SOLO, 2009, ISBN 9782757202524

- ↑ Samuel Mark: From Egypt to Mesopotamia: a Study of Predynastic Trade Routes, Texas A & M University Press, new edition 2006, ISBN 978-1585445301.

- ↑ Letter of G. Benedite to C. Boreux, Departement des Antiquites Egyptiennes, Louvre

- ↑ G. Bénédite: Le couteau de Gebel el-'Arak, Étude sur un nouvelle objet préhistorique acquis par le musée du Louvre, Fondation Eugène Piot, Monuments et mémoires, XXII, 1916 p. 1–34

- ↑ Archives de la Direction des Musées de France, AE 16, devis du 31 mars 1933

- ↑ Diane L. Holmes: Archaeological Cultural Resources and Modern Land-use Activities: Some Observations Made during a Recent Survey in the Badari Region, Egypt, JARCE XXIX (1992), pp. 67–80

- ↑ P. Kelterborn: Toward Replicating Egyptian Predynastic Flint Knives, Journal of Archeological Science 11, 1984, p. 433–453

- ↑ Online notice of the Louvre

- ↑ Béatrix Midant-Reynes: Contribution à l'étude de la société prédynastique: le cas du couteau "Ripple-flake", SAK 14, 1987, p. 185–225

- ↑ C2RMF report, M. Christensen 1999

- ↑ Winifred Needler: Predynastic and Archaic Egypt in the Brooklyn Museum, 1984, p. 37 & 153, ISBN 0872730999

- ↑ Francois Poplin: L'ivoire et la Pierre a Feu — Le Couteau Predynastique en Hippopotame de Shiqmim et le Lion d'Aristote in La Pierre prehistorique, 1992, Laboratoire de Recherche des Musées de France, pp. 187–194, ISBN 978-2-9506212-0-7

- ↑ Barbara Watterson, The Egyptians, Blackwell Publishing 1997, ISBN 0-631-21195-0, p. 41

- ↑ Robert du Mesnil du Buisson: "Le décor asiatique du couteau de Gebel el-Arak", in BIFAO 68 (1969), pp. 63–83, Online version

- ↑ Rohl, David M., Legend, the Genesis of Civilisation, 1988

- ↑ Sumerian King List column III, 1-5

- ↑ Grimal, op.cit., p. 36

- ↑ E. G. Dreyer: "Motive und Datierung der dekorierten prädynastischen Messergriffe", in L'Art de l'Ancien Empire égyptien, Actes du colloque organisé au musée du Louvre par le Service culturel les 3 et 4 avril 1998, 1999, p. 197–226, ISBN 978-2110042644

- ↑ H. Whitehouse: "A Decorated Knife Handle from the 'Main Deposit' at Hierakonpolis", MDAIK 48, 2002, p. 425–446

- ↑ Ritual knife of the Brooklyn Museum

- ↑ See the online catalog of the MET.

- ↑ S. Quirke and A.J. Spencer: British Museum Book of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, 1996, ISBN 0500279020.

- ↑ Pitt-Rivers knife on the British Museum website.

- ↑ C. S. Churcher: "A Zoological study of the ivory knife handle from Abu Zaidan", in Winifred Needler, Predynastic and Archaic Egypt in the Brooklyn Museum, 1984, ISBN 0872730999.

- ↑ Ulrich Hartung: Prädynastische Siegelabrollungen aus dem Friedhof U in Abydos (Umm el-Qaab), Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Abteilung Kairo (MDAIK) 54, 1998, pp. 187–217

- ↑ James Edward Quibell: Archaic Objects in Catalogue général des Antiquites Égyptiennes du Musée du Caire, 1904, available copyright-free online

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 John Baines: Symbolic roles of canine figures on early monuments, Archéo-Nil: Revue de la société pour l'étude des cultures prépharaoniques de la vallée du Nil, 3, 57–74, 1993. Available online

- ↑ Bruce Williams, Thomas J. Logan, and William J. Murnane: "The Metropolitan Museum Knife Handle and Aspects of Pharaonic Imagery before Narmer" in Journal of Near Eastern Studies 46, 4, October 1987, pp. 245–285.

- ↑ Diane L. Holmes: The Predynastic Lithic Industries of Upper Egypt. A Comparative Study of the Lithic Traditions of Badari, Naqada and Hierakonpolis, 1989, Oxford, B.A.R. (15)

- Nicolas-Christophe Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Publishing 1992, ISBN 0-631-19396-0, pp. 29ff.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gebel el Arak Knife. |