Gaussian free field

In probability theory and statistical mechanics, the Gaussian free field (GFF) is a Gaussian random field, a central model of random surfaces (random height functions). Sheffield (2007) gives a mathematical survey of the Gaussian free field.

The discrete version can be defined on any graph, usually a lattice in d-dimensional Euclidean space. The continuum version is defined on Rd or on a bounded subdomain of Rd. It can be thought of as a natural generalization of one-dimensional Brownian motion to d time (but still one space) dimensions; in particular, the one-dimensional continuum GFF is just the standard one-dimensional Brownian motion or Brownian bridge on an interval.

In the theory of random surfaces, it is also called the harmonic crystal. It is also the starting point for many constructions in quantum field theory, where it is called the Euclidean bosonic massless free field. A key property of the 2-dimensional GFF is conformal invariance, which relates it in several ways to the Schramm-Loewner Evolution, see Sheffield (2005) and Dubédat (2007).

Similarly to Brownian motion, which is the scaling limit of a wide range of discrete random walk models (see Donsker's theorem), the continuum GFF is the scaling limit of not only the discrete GFF on lattices, but of many random height function models, such as the height function of uniform random planar domino tilings, see Kenyon (2001). The planar GFF is also the limit of the fluctuations of the characteristic polynomial of a random matrix model, the Ginibre ensemble, see Rider & Virág (2007).

The structure of the discrete GFF on any graph is closely related to the behaviour of the simple random walk on the graph. For instance, the discrete GFF plays a key role in the proof by Ding, Lee & Peres (2012) of several conjectures about the cover time of graphs (the expected number of steps it takes for the random walk to visit all the vertices).

Definition of the discrete GFF

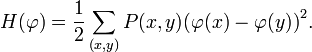

Let P(x, y) be the transition kernel of the Markov chain given by a random walk on a finite graph G(V, E). Let U be a fixed non-empty subset of the vertices V, and take the set of all real-valued functions  with some prescribed values on U. We then define a Hamiltonian by

with some prescribed values on U. We then define a Hamiltonian by

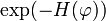

Then, the random function with probability density proportional to  with respect to the Lebesgue measure on

with respect to the Lebesgue measure on  is called the discrete GFF with boundary U.

is called the discrete GFF with boundary U.

It is not hard to show that the expected value ![\mathbb{E}[\varphi(x)]](../I/m/70c37c624938d0ca93c0f3a4b66a9546.png) is the discrete harmonic extension of the boundary values from U (harmonic with respect to the transition kernel P), and the covariances

is the discrete harmonic extension of the boundary values from U (harmonic with respect to the transition kernel P), and the covariances ![\mathrm{Cov}[\varphi(x),\varphi(y)]](../I/m/7f479f3f829849db94962b01243259d1.png) are equal to the discrete Green's function G(x, y).

are equal to the discrete Green's function G(x, y).

So, in one sentence, the discrete GFF is the Gaussian random field on V with covariance structure given by the Green's function associated to the transition kernel P.

The continuum field

The definition of the continuum field necessarily uses some abstract machinery, since it does not exist as a random height function. Instead, it is a random generalized function, or in other words, a distribution on distributions (with two different meanings of the word "distribution").

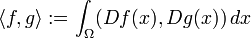

Given a domain Ω ⊆ Rn, consider the Dirichlet inner product

for smooth functions ƒ and g on Ω, coinciding with some prescribed boundary function on  , where

, where  is the gradient vector at

is the gradient vector at  . Then take the Hilbert space closure with respect to this inner product, this is the Sobolev space

. Then take the Hilbert space closure with respect to this inner product, this is the Sobolev space  .

.

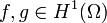

The continuum GFF  on

on  is a Gaussian random field indexed by

is a Gaussian random field indexed by  , i.e., a collection of Gaussian random variables, one for each

, i.e., a collection of Gaussian random variables, one for each  , denoted by

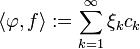

, denoted by  , such that the covariance structure is

, such that the covariance structure is ![\mathrm{Cov}[\langle \varphi,f \rangle, \langle \varphi,g \rangle] = \langle f,g \rangle](../I/m/e630db2774409e3aa9d9bd863fa99d13.png) for all

for all  .

.

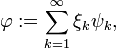

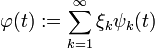

Such a random field indeed exists, and its distribution is unique. Given any orthonormal basis  of

of  (with the given boundary condition), we can form the formal infinite sum

(with the given boundary condition), we can form the formal infinite sum

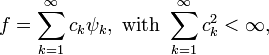

where the  are i.i.d. standard normal variables. This random sum almost surely will not exist as an element of

are i.i.d. standard normal variables. This random sum almost surely will not exist as an element of  , since its variance is infinite. However, it exists as a random generalized function, since for any

, since its variance is infinite. However, it exists as a random generalized function, since for any  we have

we have

hence

is a well-defined finite random number.

Special case: n = 1

Although the above argument shows that  does not exist as a random element of

does not exist as a random element of  , it still could be that it is a random function on

, it still could be that it is a random function on  in some larger function space. In fact, in dimension

in some larger function space. In fact, in dimension  , an orthonormal basis of

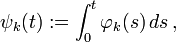

, an orthonormal basis of ![H^1[0,1]](../I/m/cbca833eabfca6413a580ea3fdab51d8.png) is given by

is given by

-

where

where  form an orthonormal basis of

form an orthonormal basis of ![L^2[0,1]\,,](../I/m/21af473f664caeaf0ebbc28dac1bdee8.png)

and then  is easily seen to be a one-dimensional Brownian motion (or Brownian bridge, if the boundary values for

is easily seen to be a one-dimensional Brownian motion (or Brownian bridge, if the boundary values for  are set up that way). So, in this case, it is a random continuous function. For instance, if

are set up that way). So, in this case, it is a random continuous function. For instance, if  is the Haar basis, then this is Lévy's construction of Brownian motion, see, e.g., Section 3 of Peres (2001).

is the Haar basis, then this is Lévy's construction of Brownian motion, see, e.g., Section 3 of Peres (2001).

On the other hand, for  it can indeed be shown to exist only as a generalized function, see Sheffield (2007).

it can indeed be shown to exist only as a generalized function, see Sheffield (2007).

Special case: n = 2

In dimension n = 2, the conformal invariance of the continuum GFF is clear from the invariance of the Dirichlet inner product.

References

- Ding, J.; Lee, J. R.; Peres, Y. (2012), "Cover times, blanket times, and majorizing measures", Annals of Mathematics 175: 1409–1471, doi:10.4007/annals.2012.175.3.8

- Dubédat, J. (2009), "SLE and the free field: Partition functions and couplings", J. Amer. Math. Soc. 22: 995–1054, doi:10.1090/s0894-0347-09-00636-5

- Kenyon, R. (2001), "Dominos and the Gaussian free field", Annals of Probability, 29, no. 3: 1128–1137, MR 1872739

- Peres, Y. (2001), "An Invitation to Sample Paths of Brownian Motion", Lecture notes at UC Berkeley

- Rider, B.; Virág, B. (2007), "The noise in the Circular Law and the Gaussian Free Field", International Mathematics Research Notices: article ID rnm006, 32 pages, MR 2361453

- Sheffield, S. (2005), "Local sets of the Gaussian Free Field", Talks at the Fields Institute, Toronto, on September 22–24, 2005, as part of the "Percolation, SLE, and related topics" Workshop.

- Sheffield, S. (2007), "Gaussian free fields for mathematicians", Probability Theory and Related Fields 139: 521–541, arXiv:math.PR/0312099, doi:10.1007/s00440-006-0050-1, MR 2322706