Gauss's lemma (number theory)

Gauss's lemma in number theory gives a condition for an integer to be a quadratic residue. Although it is not useful computationally, it has theoretical significance, being involved in some proofs of quadratic reciprocity.

It made its first appearance in Carl Friedrich Gauss's third proof (1808)[1] of quadratic reciprocity and he proved it again in his fifth proof (1818).[2]

Statement of the lemma

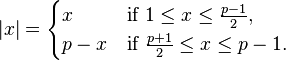

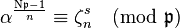

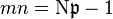

For any odd prime p let a be an integer that is coprime to p.

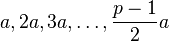

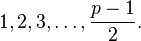

Consider the integers

and their least positive residues modulo p. (These residues are all distinct, so there are (p−1)/2 of them.)

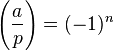

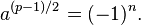

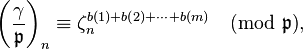

Let n be the number of these residues that are greater than p/2. Then

where (a/p) is the Legendre symbol.

Example

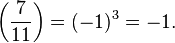

Taking p = 11 and a = 7, the relevant sequence of integers is

- 7, 14, 21, 28, 35.

After reduction modulo 11, this sequence becomes

- 7, 3, 10, 6, 2.

Three of these integers are larger than 11/2 (namely 6, 7 and 10), so n = 3. Correspondingly Gauss's lemma predicts that

This is indeed correct, because 7 is not a quadratic residue modulo 11.

The above sequence of residues

- 7, 3, 10, 6, 2

may also be written

- -4, 3, -1, -5, 2.

In this form, the integers larger than 11/2 appear as negative numbers. It is also apparent that the absolute values of the residues are a permutation of the residues

- 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

Proof

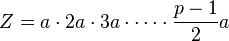

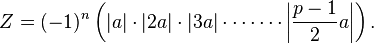

A fairly simple proof[3] of the lemma, reminiscent of one of the simplest proofs of Fermat's little theorem, can be obtained by evaluating the product

modulo p in two different ways. On one hand it is equal to

The second evaluation takes more work. If x is a nonzero residue modulo p, let us define the "absolute value" of x to be

Since n counts those multiples ka which are in the latter range, and since for those multiples, −ka is in the first range, we have

Now observe that the values |ra| are distinct for r = 1, 2, ..., (p−1)/2. Indeed, we have

- |ra| ≡ |sa| (mod p),

- ra ≡ ±sa (mod p),

- r ≡ ±s (mod p) (because a is coprime to p), and

This gives r=s, since r,s are positive least residues. But there are exactly (p−1)/2 of them, so their values are a rearrangement of the integers 1, 2, ..., (p−1)/2. Therefore,

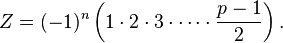

Comparing with our first evaluation, we may cancel out the nonzero factor

and we are left with

This is the desired result, because by Euler's criterion the left hand side is just an alternative expression for the Legendre symbol (a/p).

Applications

Gauss's lemma is used in many,[4][5] but by no means all, of the known proofs of quadratic reciprocity.

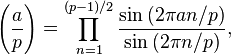

For example, Eisenstein[6] used Gauss's lemma to prove that if p is an odd prime then

and used this formula to prove quadratic reciprocity, (and, by using elliptic rather than circular functions, to prove the cubic and quartic reciprocity laws.[7])

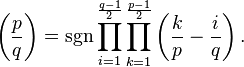

Kronecker[8] used the lemma to show that

Switching p and q immediately gives quadratic reciprocity.

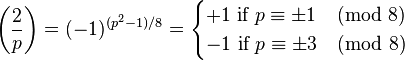

It is also used in what are probably the simplest proofs of the "second supplementary law"

Higher powers

Generalizations of Gauss's lemma can be used to compute higher power residue symbols. In his second monograph on biquadratic reciprocity,[9] Gauss used a fourth-power lemma to derive the formula for the biquadratic character of 1 + i in Z[i], the ring of Gaussian integers. Subsequently,[10] Eisenstein used third- and fourth-power versions to prove cubic and quartic reciprocity.

nth power residue symbol

Let k be an algebraic number field with ring of integers  and let

and let  be a prime ideal. The ideal norm of

be a prime ideal. The ideal norm of  is defined as the cardinality of the residue class ring (since

is defined as the cardinality of the residue class ring (since  is prime this is a finite field)

is prime this is a finite field)

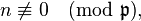

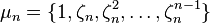

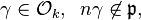

Assume that a primitive nth root of unity  and that n and

and that n and  are coprime (i.e.

are coprime (i.e.  ) Then

) Then

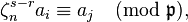

No two distinct nth roots of unity can be congruent

The proof is by contradiction: assume otherwise, that  Then letting

Then letting  and

and  From the definition of roots of unity,

From the definition of roots of unity,

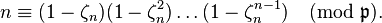

and dividing by x − 1 gives

and dividing by x − 1 gives

Letting x = 1 and taking residues

Since n and  are coprime,

are coprime,  but under the assumption, one of the factors on the right must be zero. Therefore the assumption that two distinct roots are congruent is false.

but under the assumption, one of the factors on the right must be zero. Therefore the assumption that two distinct roots are congruent is false.

Thus the residue classes of  containing the powers of ζn are a subgroup of order n of its (multiplicative) group of units,

containing the powers of ζn are a subgroup of order n of its (multiplicative) group of units,  Therefore the order of

Therefore the order of  is a multiple of n, and

is a multiple of n, and

There is an analogue of Fermat's theorem in  If

If  then[11]

then[11]

and since

and since

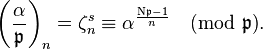

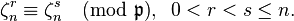

is well-defined and congruent to a unique nth root of unity ζns.

is well-defined and congruent to a unique nth root of unity ζns.

This root of unity is called the nth-power residue symbol for  and is denoted by

and is denoted by

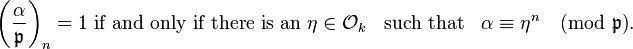

It can be proven that[12]

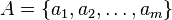

1/n systems

Let  be the multiplicative group of the nth roots of unity, and let

be the multiplicative group of the nth roots of unity, and let  be representatives of the cosets of

be representatives of the cosets of  Then A is called a 1/n system

Then A is called a 1/n system  [13]

[13]

In other words, there are  numbers in the set

numbers in the set  and this set constitutes a representative set for

and this set constitutes a representative set for

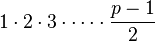

The numbers 1, 2, ..., (p − 1)/2, used in the original version of the lemma, are a 1/2 system (mod p).

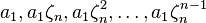

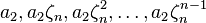

Constructing a 1/n system is straightforward: let M be a representative set for  Pick any

Pick any  and remove the numbers congruent to

and remove the numbers congruent to  from M. Pick a2 from M and remove the numbers congruent to

from M. Pick a2 from M and remove the numbers congruent to  Repeat until M is exhausted. Then {a1, a2, ... am} is a 1/n system

Repeat until M is exhausted. Then {a1, a2, ... am} is a 1/n system

The lemma for nth powers

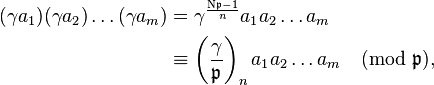

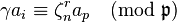

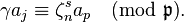

Gauss's lemma for the nth power residue symbol is[14]

Let  be a primitive nth root of unity,

be a primitive nth root of unity,  a prime ideal,

a prime ideal,  (i.e.

(i.e.  is coprime to both γ and n) and let A = {a1, a2,..., am} be a 1/n system

is coprime to both γ and n) and let A = {a1, a2,..., am} be a 1/n system

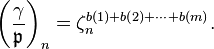

Then for each i, 1 ≤ i ≤ m, there are integers π(i), unique (mod m), and b(i), unique (mod n), such that

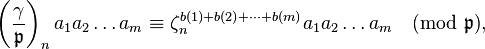

and the nth-power residue symbol is given by the formula

The classical lemma for the quadratic Legendre symbol is the special case n = 2, ζ2 = −1, A = {1, 2, ..., (p − 1)/2}, b(k) = 1 if ak > p/2, b(k) = 0 if ak < p/2.

Proof

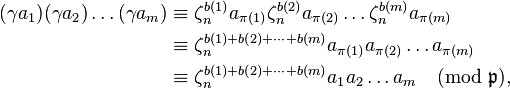

The proof of the nth-power lemma uses the same ideas that were used in the proof of the quadratic lemma.

The existence of the integers π(i) and b(i), and their uniqueness (mod m) and (mod n), respectively, come from the fact that Aμ is a representative set.

Assume that π(i) = π(j) = p, i.e.

and

and

Then

Because γ and  are coprime both sides can be divided by γ, giving

are coprime both sides can be divided by γ, giving

which, since A is a 1/n system, implies s = r and i = j, showing that π is a permutation of the set {1, 2, ..., m}.

Then on the one hand, by the definition of the power residue symbol,

and on the other hand, since π is a permutation,

so

and since for all 1 ≤ i ≤ m, ai and  are coprime, a1a2...am can be cancelled from both sides of the congruence,

are coprime, a1a2...am can be cancelled from both sides of the congruence,

and the theorem follows from the fact that no two distinct nth roots of unity can be congruent (mod  ).

).

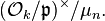

Relation to the transfer in group theory

Let G be the multiplicative group of nonzero residue classes in Z/pZ, and let H be the subgroup {+1, −1}. Consider the following coset representatives of H in G,

Applying the machinery of the transfer to this collection of coset representatives, we obtain the transfer homomorphism

which turns out to be the map that sends a to (−1)n, where a and n are as in the statement of the lemma. Gauss's lemma may then be viewed as a computation that explicitly identifies this homomorphism as being the quadratic residue character.

See also

Two other characterizations of squares modulo a prime are Euler's criterion and Zolotarev's lemma.

Notes

- ↑ "Neuer Beweis eines arithmetischen Satzes"; pp 458-462 of Untersuchungen uber hohere Arithmetik

- ↑ "Neue Beweise und Erweiterungen des Fundalmentalsatzes in der Lehre von den quadratischen Reste"; pp 496-501 of Untersuchungen uber hohere Arithmetik

- ↑ Any textbook on elementary number theory will have a proof. The one here is basically Gauss's from "Neuer Beweis eines arithnetischen Satzes"; pp 458-462 of Untersuchungen uber hohere Arithmetik

- ↑ Lemmermeyer, ch. 1

- ↑ Lemmermeyer, p. 9, "like most of the simplest proofs [ of QR], [Gauss's] 3 and 5 rest on what we now call Gauss's Lemma

- ↑ Lemmermeyer, p. 236, Prop 8.1 (1845)

- ↑ Lemmermeyer, ch. 8

- ↑ Lemmermeyer, ex. 1.34 (The year isn't clear because K. published 8 proofs, several based on Gauss's lemma, between 1875 and 1889)

- ↑ Gauss, BQ, §§ 69–71

- ↑ Lemmermeyer, Ch. 8

- ↑ Lemmermeyer, Ch. 4.1

- ↑ Lemmermeyer, Prop 4.1

- ↑ Lemmermeyer, Ch. 4.2

- ↑ Lemmermeyer, Prop. 4.3

References

The two monographs Gauss published on biquadratic reciprocity have consecutively numbered sections: the first contains §§ 1–23 and the second §§ 24–76. Footnotes referencing these are of the form "Gauss, BQ, § n".

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1828), Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum, Commentatio prima, Göttingen: Comment. Soc. regiae sci, Göttingen 6

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1832), Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum, Commentatio secunda, Göttingen: Comment. Soc. regiae sci, Göttingen 7

These are in Gauss's Werke, Vol II, pp. 65–92 and 93–148

German translations of the above are in the following, which also has the Disquisitiones Arithmeticae and Gauss's other papers on number theory, including the six proofs of quadratic reciprocity.

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich; Maser, H. (translator into German) (1965), Untersuchungen uber hohere Arithmetik (Disquisitiones Arithmeticae & other papers on number theory) (Second edition), New York: Chelsea, ISBN 0-8284-0191-8

- Lemmermeyer, Franz (2000), Reciprocity Laws: from Euler to Eisenstein, Berlin: Springer, ISBN 3-540-66957-4