Gareth Jones (journalist)

| Gareth Richard Vaughan Jones | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

13 August 1905 Barry, Vale of Glamorgan |

| Died | 12 August 1935 (aged 29) |

| Nationality | Welsh |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Website | |

|

www | |

Gareth Richard Vaughan Jones (13 August 1905 – 12 August 1935) was a Welsh journalist who first publicised the existence of the Great Ukrainian Famine of 1932–33, the Holodomor, in the Western world.

Life and career

Jones was born in Barry, Vale of Glamorgan. His father Major Edgar Jones was headmaster of Barry County School which Gareth attended. His mother had spent the period 1889–1892 as tutor to the children of Arthur Hughes, the son of Welsh steel industrialist John Hughes, who had founded the town of Yuzovka, modern day Donetsk, in Ukraine, and her stories inspired in Jones a desire to visit the Soviet Union, and particularly Ukraine.

Jones graduated from the University of Wales, Aberystwyth in 1926 with a first class degree in French, and from Trinity College, Cambridge in 1929 with a first class honours degree in French, German, and Russian.[1] In January 1930 he began work as Foreign Affairs Advisor to former British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, and that summer made his first brief "pilgrimage" to Yuzovka (by then renamed Stalino).

In 1931 he was offered employment in New York City by Dr Ivy Lee, public relations advisor to organisations such as the Rockefeller Institute, the Chrysler Foundation, and Standard Oil, to research a book about the Soviet Union. In the summer of 1931 he toured the Soviet Union with H. J. Heinz II of the food company dynasty, producing a diary published by Heinz as Experiences in Russia 1931, a diary which probably contains the first usage of the word "starve" in relation to the collectivisation of Soviet agriculture. In 1932 Jones returned to work for Lloyd George and helped the wartime Prime Minister write his War Memoirs.

In late January and early February 1933 Jones was in Germany covering the accession to power of the Nazi Party, and was in Leipzig on the day Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor. A few days later he flew with Hitler to Frankfurt and reported on the new Chancellors' tumultuous acclamation in that city. The next month he travelled to Russia and Ukraine, and on his return to Berlin on 29 March 1933, he issued his famous press release which was published by many newspapers including the Manchester Guardian and the New York Evening Post:

I walked along through villages and twelve collective farms. Everywhere was the cry, 'There is no bread. We are dying'. This cry came from every part of Russia, from the Volga, Siberia, White Russia, the North Caucasus, and Central Asia. I tramped through the black earth region because that was once the richest farmland in Russia and because the correspondents have been forbidden to go there to see for themselves what is happening.In the train a Communist denied to me that there was a famine. I flung a crust of bread which I had been eating from my own supply into a spittoon. A peasant fellow-passenger fished it out and ravenously ate it. I threw an orange peel into the spittoon and the peasant again grabbed it and devoured it. The Communist subsided. I stayed overnight in a village where there used to be two hundred oxen and where there now are six. The peasants were eating the cattle fodder and had only a month's supply left. They told me that many had already died of hunger. Two soldiers came to arrest a thief. They warned me against travel by night, as there were too many 'starving' desperate men.

'We are waiting for death' was my welcome, but see, we still, have our cattle fodder. Go farther south. There they have nothing. Many houses are empty of people already dead,' they cried.

This report was unwelcome in a great many of the media, as the intelligentsia of the time was still in sympathy with the Soviet regime. On 31 March the New York Times published a denial of Jones' statement by Walter Duranty under the headline "RUSSIANS HUNGRY, BUT NOT STARVING".[2] In the article, Kremlin sources denied the existence of a famine, and said, "Russian and foreign observers in country could see no grounds for predications of disaster". On 13 May, Jones published a strong rebuttal to Duranty in the New York Times, standing by his report:[3]

My first evidence was gathered from foreign observers. Since Mr. Duranty introduces consuls into the discussion, a thing I am loath to do, for they are official representatives of their countries and should not be quoted, may I say that I discussed the Russian situation with between twenty and thirty consuls and diplomatic representatives of various nations and that their evidence supported my point of view. But they are not allowed to express their views in the press, and therefore remain silent.Journalists, on the other hand, are allowed to write, but the censorship has turned them into masters of euphemism and understatement. Hence they give "famine" the polite name of 'food shortage' and 'starving to death' is softened down to read as 'widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition'. Consuls are not so reticent in private conversation.

In a personal letter from Soviet Foreign Commissar Maxim Litvinov (whom Jones had interviewed while in Moscow) to Lloyd George, Jones was informed that he was banned from ever visiting the Soviet Union again.

Banned from Russia, Jones turned his attention to the Far East and in late 1934 he left Britain on a "Round-the-World Fact-Finding Tour". He spent about six weeks in Japan, interviewing important Generals and politicians, and he eventually reached Beijing. From here he travelled to Inner Mongolia in newly Japanese-occupied Manchukuo in the company of a German journalist. Detained by Japanese forces, the pair were told that there were three routes back to the Chinese town of Kalgan, only one of which was safe; they took this route but were captured by bandits who demanded a ransom of 100,000 Mexican silver pesos. The German journalist was released after two days, but 16 days later the bandits shot Jones under mysterious circumstances, on the eve of his 30th birthday. There were strong suspicions that Jones' murder was engineered by the Soviet NKVD, as revenge for the embarrassment he had previously caused the Soviet regime.[4]

On 26 August 1935, the London Evening Standard quoted Lloyd George paying tribute to Jones:

That part of the world is a cauldron of conflicting intrigue and one or other interests concerned probably knew that Mr Gareth Jones knew too much of what was going on... He had a passion for finding out what was happening in foreign lands wherever there was trouble, and in pursuit of his investigations he shrank from no risk... I had always been afraid that he would take one risk too many. Nothing escaped his observation, and he allowed no obstacle to turn from his course when he thought that there was some fact, which he could obtain. He had the almost unfailing knack of getting at things that mattered.

Memorial

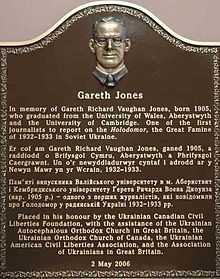

On 2 May 2006, a trilingual (Welsh/English/Ukrainian) plaque was unveiled in Gareth Jones' memory in the Old College at Aberystwyth University, in the presence of his niece Margaret Siriol Colley, and the Ukrainian Ambassador to the UK, Ihor Kharchenko, who described him as an "unsung hero of Ukraine". The idea for a plaque and funding were provided by the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association, working in conjunction with the Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain. Dr Lubomyr Luciuk, UCCLA's director of research, spoke at the unveiling ceremony.

In November 2008, Jones and fellow Holodomor journalist Malcolm Muggeridge were posthumously awarded the Ukrainian Order of Merit at a ceremony in Westminster Central Hall, by Ambassador of Ukraine to the UK, Dr Ihor Kharchenko, on behalf of the President of Ukraine in reward for their exceptional services to the country and its people.[5][6]

References

- ↑ "'Unsung hero' reporter remembered". BBC News. 2006-05-02. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

- ↑ Walter Duranty (31 March 1933). "RUSSIANS HUNGRY, BUT NOT STARVING; Deaths From Diseases Due to Malnutrition High, Yet the Soviet Is Entrenched". The New York Times: 13. Archived from the original on 2009-01-01.

- ↑ Gareth Jones (13 May 1933). "Mr. Jones Replies; Former Secretary of Lloyd George Tells of Observations in Russia". The New York Times: 12. Archived from the original on 2009-01-01.

- ↑ "Journalist Gareth Jones' 1935 murder examined by BBC Four". BBC News. 2012-07-05. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ↑ "Ukraine to honour Welsh reporter". BBC Wales. 2008-11-22. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- ↑ "Telling the truth about the Ukrainian famine". National Post (Canada). 2008-11-22. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

External links

- Gareth Jones commemorative website

- Canadian Civil Liberties Association website

- Short biography of Gareth Jones by his niece, Margaret Siriol Colley. Includes links to newspaper articles written by Jones from around the world.

- "'Unsung hero' reporter remembered". BBC News. 2006-05-02. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

- Documentary film "Hitler, Stalin, and Mr. Jones" by George Carey. Retrieved 2014-09-28.

|