Garda Síochána

| An Garda Síochána | |

| Common name | Gardaí |

| |

| Shield of An Garda Síochána | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1922[1] |

| Preceding agencies | |

| Annual budget | €1.426 billion (2015) [2] |

| Legal personality | Governmental: Government agency |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| National agency | Ireland |

| |

| An Garda Síochána area of jurisdiction in dark blue | |

| Size | 70,273 km² |

| Population | 4,581,269 |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | Garda Headquarters, Phoenix Park, Dublin |

| Officers | 12,900 |

| Sections | 14

|

| Regions | 6 |

| Facilities | |

| Stations | 564 |

| Marine/Sub-Aquas | Garda Water Unit |

| Aircraft | Defender (fixed wing) and EC135 (helicopters x2) |

| Canines | Garda Dog Unit |

| Website | |

| www | |

An Garda Síochána (Irish pronunciation: [ən ˈɡaːrd̪ə ˈʃiːxaːn̪ˠə]; meaning "the Guardian of the Peace"), more commonly referred to as the Gardaí ([ˈɡaːɾˠd̪ˠiː] gar-DEE, "Guardians"), is the police force of Ireland. The service is headed by the Garda Commissioner who is appointed by the Irish government. Its headquarters are in Dublin's Phoenix Park.

Terminology

The force was originally named the Civic Guard in English,[3] but in 1923 it became An Garda Síochána in both English and Irish. This is usually translated as "the Guardian(s) of the Peace".[4] Garda Síochána na hÉireann ("of Ireland", Irish pronunciation: [ˈɡaːrd̪ə ˈʃiːxaːn̪ˠə n̪ˠə ˈheːɾʲən̪ˠ]) appears on its logo but is seldom used elsewhere.

The full official title of the force is rarely used in speech. How it is referred to depends on the register of the speaker. It is variously known as An Garda Síochána; the Garda Síochána; the Garda; the Gardaí (plural); and it is popularly called "the guards".[5] Although Garda is singular, in these terms it is used as a collective noun, like police.

An individual officer is called a garda (plural gardaí), or, informally, a "guard". A police station is called a Garda station. Garda is also the name of lowest rank within the force (e.g. "Garda John Murphy", analogous to the British term "constable" or the American "officer", "deputy", "trooper", etc.). "Guard" is the most common form of address used by members of the public speaking to a garda on duty. A female officer was once officially referred to as a bangharda ([ˈbˠanˌɣaːɾˠd̪ˠə]; "female guard"; plural banghardaí). This term was abolished in 1990,[6] but is still used colloquially in place of the now gender-neutral garda.

Organisation

| Rank | Irish name | Number of operatives (31 August 2014)[7] |

|---|---|---|

| Commissioner | Coimisinéir | 1 |

| Deputy Commissioner | Leas-Choimisinéir | 0 |

| Assistant Commissioner | Cúntóir-Choimisinéir | 8 |

| Chief Superintendent | Príomh-Cheannfort | 41 |

| Superintendent | Ceannfort | 140 |

| Inspector | Cigire | 300 |

| Sergeant | Sáirsint | 1,946 |

| Gardaí | Gardaí | 10,459 |

| Reserve Gardaí | Gardaí Ionaid | 1,112 |

| Student Gardaí | Mac Léinn Ghardaí | 200 |

The force is headed by the Commissioner, whose immediate subordinates are two Deputy Commissioners – in charge of "Operations" and "Strategy and Change Management", respectively – and a Chief Administrative Officer with responsibility for resource management (personnel, finance, Information and Communications Technology, and accommodation). There are twelve Assistant Commissioners: one for each of the six geographical Regions, and the remainder dealing with various national support functions. At an equivalent or near-equivalent level to the Assistant Commissioners are the positions of Chief Medical Officer, Executive Director of Information and Communications Technology, and Executive Director of Finance.

The six geographical Assistant Commissioners command the six Garda Force Regions, which are currently:

- Dublin Metropolitan Region

- Eastern

- Northern

- Southern

- South-Eastern

- Western

Directly subordinate to the Assistant Commissioners are approximately 50 Chief Superintendents, about half of whom supervise what are called Divisions. Each Division contains a number of Districts, each commanded by a Superintendent assisted by a team of Inspectors. Each District contains a number of Subdistricts, which are usually commanded by Sergeants.

Typically each Subdistrict contains only one Garda station. A different number of Gardaí are based at each station depending on its importance. Most of these stations employ the basic rank of Garda, which was referred to as the rank of Guard until 1972. The most junior members of the force are students, whose duties can vary depending on their training progress. They are often bestowed with clerical duties, as part of their extra curriculum studies.

The Garda organisation also has over 2,500 non-officer support staff encompassing a diverse range of areas such as human resources, occupational health services, finance and procurement, internal audit, IT and telecommunications, accommodation and fleet management, scenes-of-crime support, research and analysis, training and general administration. The figure also includes industrial staff such as traffic wardens, drivers and cleaners. It is ongoing government policy to bring the level of non-officer support in the organisation up to international standards – thus enhancing its capacity and expertise in a range of specialist and administrative functions, and releasing more of its police officers for core operational duties.

Reserve Gardaí

The Garda Síochána Act 2005 provided for the establishment of a Garda Reserve to assist the force in performing its functions, and supplement the work of members of the Garda Síochána.

The intent of the Garda Reserve is "to be a source of local strength and knowledge". Reserve members are to carry out duties defined by the Garda Commissioner and sanctioned by the Minister for Justice and Equality. With reduced training of 128 hours, these duties and powers must be operated under the supervision of regular members of the Force, and are also limited from those of regular members.

As of November 2010 there are 850 graduated Reserve Gardaí, and another 148 in further training. The first batch of 36 Reserve Gardaí graduated on 15 December 2006 at the Garda College, in Templemore.[8]

Sections

- Bureau of Fraud Investigation

- Central Vetting Unit

- Community Relations Unit

- Garda Information Services Centre

- Garda Síochána College

- Garda Síochána Reserve

- Garda Traffic Corps

- National Bureau of Criminal Investigation

- Garda National Immigration Bureau

- Garda National Drug Unit

- Garda Regional Support Units

- Garda Crime & Security Branch consists of;

- Operational Support Unit that consists of;

- Organised Crime Unit

- Garda Public Order Unit

- Garda Technical Bureau

Rank structure

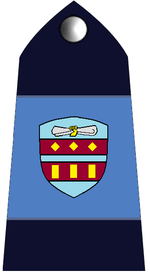

| Rank | Student Reserve | Student | Garda Reserve | Garda | Sergeant | Inspector | Superintendent | Chief Superintendent | Assistant Commissioner | Deputy Commissioner | Commissioner |

| Insignia |  |  |  |  |

Equipment

Most uniformed members of An Garda Síochána do not routinely carry firearms. Individual Gardaí have been issued with ASP extendable batons and pepper spray as their standard issue weapons while handcuffs are equipped as restraints.[9]

The force, when originally created, was armed, but the Provisional Government reversed the decision and reconstituted the force as an unarmed police force. This was in contrast to the attitude of the British Dublin Castle administration, which refused appeals from the Royal Irish Constabulary that the force be disarmed.[10] In the words of first Commissioner, Michael Staines, TD, "the Garda Síochána will succeed not by force of arms or numbers, but on their moral authority as servants of the people."

According to Tom Garvin such a decision gave the new force a cultural ace: "the taboo on killing unarmed men and women who could not reasonably be seen as spies and informers."[10]

Armed Gardaí

The Gardai is primarily an unarmed force, however, certain units such as the Special Detective Unit (SDU), Regional Support Units (RSU), and the Emergency Response Unit (ERU) are commissioned to and so carry firearms.

The armed officers serve as a fall back to regular Gardaí, created in response to a rise in the number of armed incidents dealt with by regular members.[11] To be issued with a firearm, or to carry a firearm whilst on duty, a member must be in possession of a valid gun card, and cannot wear a regular uniform.

Armed Gardaí carry Sig Sauer P226 and Walther P99C semi-automatic pistols. Armed intervention units and specialist Detective units carry a variety of long arms, primarily the Heckler & Koch MP7 sub-machine guns as the standard issue weapon alongside with the Heckler & Koch MP5.

In addition to issued pistols, less-lethal weapons such as tasers and large pepper spray canisters are carried also by the ERU.[12]

Diplomatic protection

The Garda Special Detective Unit (SDU) are primarily responsibility for providing armed close protection to senior officials in Ireland.[13] They provide full-time armed protection and transport for; the President, Taoiseach, Tánaiste, Minister for Justice and Equality, Attorney General, Chief Justice, Director of Public Prosecutions, Ambassadors and Diplomats deemed 'at risk' (such as the Ambassadors, Embassies and Diplomatic Residences of the United Kingdom, United States, Israel), as well as foreign dignitaries visiting Ireland and citizens deemed to require armed protection as designated so by the Garda Commissioner.[14] The Commissioner is also protected by the unit. All cabinet ministers are afforded armed protection at heightened levels of risk when deemed necessary by Garda Intelligence,[15] and their places of work and residences are monitored.[16] Former Presidents and Taoisigh are protected if their security is under threat, otherwise they only receive protection on formal state occasions.[17] The Emergency Response Unit (ERU), a section of the SDU, are deployed on more than 100 VIP protection duties per year.[18]

Vehicles

Garda patrol cars are white or silver in colour, with a fluorescent yellow and blue bordered horizontal strip, accompanied by the Garda crest as livery. Traffic Corps vehicles adopt a half battenburg pattern. Unmarked patrol cars are also used in the course of regular, traffic and investigatory duties.

History

The Civic Guard was formed by the Provisional Government in February 1922 to take over the responsibility of policing the fledgling Irish Free State. It replaced the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the Irish Republican Police of 1919–22. In August 1922 the force accompanied Michael Collins when he met the Lord Lieutenant in Dublin Castle.[19]

The Garda Síochána (Temporary Provisions) Act 1923 enacted after the creation of the Irish Free State on 8 August 1923,[20] provided for the creation of "a force of police to be called and known as 'The Garda Síochána'". Under section 22, The Civic Guard were deemed to have been established under and to be governed by the Act. The law therefore effectively renamed the existing force.

During the Civil War of 1922–23, the new Free State set up the Criminal Investigation Department as an armed, plain-clothed counter-insurgency unit. It was disbanded after the end of the war in October 1923 and elements of it were absorbed into the Dublin Metropolitan Police.

In Dublin, policing remained the responsibility of the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP, founded 1836) until it merged with the Garda Síochána in 1925. Since then the Garda has been the only civil police force in the state now known as Ireland. Other police forces with limited powers are the Military Police within the Irish Defence Forces, the Airport Police Service, and Dublin Port and Dún Laoghaire Harbour police forces.

Scott Medal

First established in 1925, the Scott Medal for Bravery is the highest honour for bravery and valour awarded to a member of the Garda Síochána. The first medals were funded by Colonel Walter Scott, an honorary Commissioner of the New York Police Department.[21] The first recipient of the Scott Medal was Pat Malone of St. Luke's Cork City who – as an unarmed Garda – disarmed Tomás Óg Mac Curtain (the son of Tomás Mac Curtain).

To mark the United States link, the American English spelling of valor is used on the medal. The Garda Commissioner chooses the recipients of the medal, which is presented by the Minister for Justice and Equality.

In 2000, Anne McCabe – the widow of Jerry McCabe, a garda who was killed by armed Provisional IRA bank robbers – accepted the Scott Medal for Bravery that had been awarded posthumously to her husband.[22]

The Irish Republican Police had at least one member killed by the RIC 21 July 1920.

The Civic Guard had one killed by accident 22 September 1922 & another was killed March 1923 by Frank Teeling. Likewise 4 members of the Oriel House Criminal Investigation Department were killed/Died of wounds during the Irish Civil War.[23] The Garda Roll of Honor lists 86 members of the Garda killed between 1922 to the present (See Below)

Garda Commissioners

| Name | From | Until | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| Michael Staines | February 1922 | September 1922 | resigned |

| Eoin O'Duffy | September 1922 | February 1933 | dismissed for encouraging military coup |

| Eamon Broy | February 1933 | June 1938 | retired |

| Michael Kinnane | June 1938 | July 1952 | died |

| Daniel Costigan | July 1952 | February 1965 | resigned |

| William P Quinn | February 1965 | March 1967 | retired |

| Patrick Carroll | March 1967 | September 1968 | retired |

| Michael Wymes | September 1968 | January 1973 | retired |

| Patrick Malone | January 1973 | September 1975 | retired |

| Edmund Garvey | September 1975 | January 1978 | replaced (lost government confidence) |

| Patrick McLaughlin | January 1978 | January 1983 | retired (wiretap scandal) |

| Lawrence Wren | February 1983 | November 1987 | retired |

| Eamonn Doherty | November 1987 | December 1988 | retired |

| Eugene Crowley | December 1988 | January 1991 | retired |

| Patrick Culligan | January 1991 | July 1996 | retired |

| Patrick Byrne | July 1996 | July 2003 | retired |

| Noel Conroy | July 2003 | November 2007 | retired |

| Fachtna Murphy | November 2007 | December 2010 | retired |

| Martin Callinan | December 2010 | March 2014 | resigned (Penalty points controversy) |

| Nóirín O'Sullivan | March 2014 | (incumbent) |

The first Commissioner, Michael Staines, who was a Pro-Treaty member of Dáil Éireann, held office for only eight months. It was his successors, Eoin O'Duffy and Éamon Broy, who played a central role in the development of the force. O'Duffy was Commissioner in the early years of the force when to many people's surprise the viability of an unarmed police force was established. O'Duffy later became a short-lived political leader of the quasi-fascist Blueshirts before heading to Spain to fight alongside Francisco Franco's Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War. Broy had greatly assisted the Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the Anglo-Irish War, while serving with the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP). Broy's fame grew in the 1990s when he featured in the film Michael Collins, in which it was misleadingly suggested that he had been murdered by the British during the War of Independence, when in reality he lived for decades and headed the Garda Síochána from 1933 to 1938. Broy was followed by Commissioners Michael Kinnane (1938–52) and Daniel Costigan (1952–65). The first Commissioner to rise from the rank of ordinary Garda was William P. Quinn, who was appointed in February 1965.

One later Commissioner, Edmund Garvey, was sacked by the Fianna Fáil government of Jack Lynch in 1978 after it had lost confidence in him. Garvey won "unfair dismissal" legal proceedings against the government, which was upheld in the Irish Supreme Court[24] This outcome required the passing of the Garda Síochána Act 1979 to retrospectively validate the actions of Garvey's successor since he had become Commissioner.[25] Garvey's successor, Patrick McLaughlin, was forced to resign along with his deputy in 1983 over his peripheral involvement in a political scandal.

On 25 November 2014 Nóirín O'Sullivan was appointed as Garda Commissioner, after acting as interim Commissioner since March 2014, following the resignation of Martin Callinan. It was noted that as a result most top justice posts in the Republic of Ireland at the time were held by women.[26] The first female to hold the top rank, Commissioner O'Sullivan joined the force in 1981, and was among the first members of a plain-clothes unit set up to tackle drug dealing in Dublin.

Past reserve forces

During the Second World War (often referred to in Ireland as "the Emergency") there were two reserve forces to the Garda Síochána, An Taca Síochána and the Local Security Force.[27]

An Taca Síochána had the power of arrest and wore uniform, and were allowed to leave the reserve or sign-up as full members of the Garda Síochána at the end of the war before the reserve was disbanded. The reserve was established by the Emergency Powers (Temporary Special Police Force) Order, 1939.

The Local Security Force (LSF) did not have the power of arrest, and part of the reserve was soon incorporated into the Irish Army Reserve under the command of the Irish Army.[28]

Inter-jurisdiction co-operation

Northern Ireland

The Patten Report recommended that a programme of long-term personnel exchanges should be established between the Garda Síochána and the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI). This recommendation was enacted in 2002 by an Inter-Governmental Agreement on Policing Cooperation, which set the basis for the exchange of officer between the two services. There are three levels of exchanges:

- Personnel exchanges, for all ranks, without policing powers and for a term up to one year

- Secondments: for ranks Sergeant to Chief Superintendent, with policing powers, for up to three years

- Lateral entry by the permanent transfer of officers for ranks above Inspector and under Assistant Commissioner

The protocols for this movements of personnel were signed by both the Chief Constable of the PSNI and the Commissioner of An Garda Síochána on 21 February 2005.[29]

Garda officers also co-operate with members of the PSNI to combat cross-border crime, and can conduct joint raids on both jurisdictions. They have also accompanied politicians from the Republic, such as the President on visits to Northern Ireland.

Other jurisdictions

Since 1989, the Garda Síochána has undertaken United Nations peace-keeping duties. Its first such mission was a 50 strong contingent sent to Namibia. Since then the force has acted in Angola, Cambodia, Cyprus, Mozambique, South Africa and the former Yugoslavia. The force's first fatality whilst working abroad was Sergeant Paul M. Reid, who was fatally injured while on duty with the United Nations UNPROFOR at "Sniper's Alley" in Sarajevo on 18 May 1995.

Members of the Garda Síochána also serve in the Embassies of Ireland in London, The Hague, Madrid and Paris. Members are also seconded to Europol in The Hague, in the Netherlands and Interpol in Lyon, France. There are also many members working directly for UN and European agencies such as the War Crimes Tribunal.

Under an agreement with the British Government and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the Garda Síochána and the Radiological Protection Institute of Ireland are allowed to inspect the Sellafield nuclear facility in Cumbria, England.

Controversy and allegations involving the force

Much like every police force in the world, the Gardaí have faced complaints or allegations of discourtesy, harassment and perjury.[30] A total of 1,173 complaints were made against the Gardaí in 2005,[31] with over 2000 complaints made in 2009.[32]

Some such incidents attracted broad attention and resulted in a number of reform initiatives—such as those relating to Garda whistleblowers or which led to the Morris and Barr Tribunals.[33] Others have been more isolated-such as a discussion in 2007 about whether a Sikh applicant to the Garda Reserve would be exempted from standard uniform dress.[34]

Mishandling of cases and complaints

The Kerry Babies case was one of the first public inquiries into mishandling of a Garda investigation. Later, in the 1980s, the Ferns Report (an inquiry into allegations of clerical sexual abuse) described as "wholly inadequate" the handling of one of eight formal complaints made to Wexford gardaí, but noted that the remaining formal complaints were handled in an "effective, professional and sensitive" manner.[35]

The Gardaí were also criticised in the Murphy Report[36] in relation to the handing over of the case of Fr. Paul McGennis to Archbishop McQuaid by Commissioner Costigan.[37] Some very senior Gardaí were criticised for regarding priests as being outside their remit in 1960.[38] On 26 November 2009, then Commissioner Fachtna Murphy apologised for the failure of An Garda Siochána to protect victims of child abuse in the Dublin Archdiocese.[39] He said that inappropriate relationships and contacts between gardaí and the Dublin Archdiocese had taken place at a time of undue or misguided deference to religious authorities and that these were incompatible with any investigation.[39] On 27 November 2009 he announced that a senior investigator would examine the findings in the report.[40]

The Gardaí were criticised by the commission of investigation into the Dean Lyons case for their handling of the investigation into the Grangegorman killings. In his report, George Birmingham said that the Gardaí had used leading questions in their interviews with Lyons, and had failed to act on a suspicion that Lyons' confession was unreliable. For a period, the gardaí involved in the case failed to act on the knowledge that another man, Mark Nash, had confessed to the crime. They were also criticised for failing to keep adequate records of their interviews with Lyons.[41]

Allegations resulting in Tribunals of Inquiry

In the 1990s and early 2000s the Garda Síochána faced allegations of corrupt and dishonest policing in County Donegal. This became the subject of a judicial inquiry: the Morris Tribunal. The tribunal found that some gardaí based in County Donegal had invented a Provisional IRA informer, made bombs and claimed credit for locating them, and attempted to frame Raphoe publican Frank McBrearty Junior for murder – the latter case involving a €1.5m settlement with the State.

On 20 April 2000, members of the Emergency Response Unit (ERU) shot dead 27-year-old John Carthy at the end of a 25-hour siege as he left his home in Abbeylara, County Longford with a loaded shotgun in his hands. There were allegations made of inappropriate handling of the situation and of the reliance of lethal force by the Gardaí. This led to a Garda inquiry, and subsequently, a Tribunal of Inquiry under Justice Robert Barr. The official findings of the tribunal were that the responsible sergeant had made 14 mistakes in his role as negotiator during the siege, and failed to make real efforts to achieve resolution during the armed stand-off. It further stated however that the sergeant was limited by lack of experience and resources (including psychologists, solicitors, dogs), and recommended a review of Garda command structures, and that the ERU be equipped with stun guns and other non-lethal options. The Barr tribunal further recommended a formal working arrangement between Gardaí and state psychologists, and improvements in Garda training.

Allegations involving abuse of powers

One of the first charges of serious impropriety against the force rose out of the handling of the Sallins Train Robbery in 1976. This case eventually led to accusations that a "Heavy Gang" within the force intimidated and tortured accused. This eventually led to a Presidential pardon for one of the accused.

In 2004, an RTÉ Prime Time documentary accused elements within the Garda of abusing their powers by physically assaulting people arrested. A retired Circuit Court judge (W. A. Murphy) suggested that some members of the force had committed perjury in criminal trials before him but later stated that he was misquoted, while Minister of State Dick Roche, accused Gardaí in one instance of "torture". The Garda Commissioner accused the television programme of lacking balance. The documentary followed the publication of footage by the Independent Media Centre showing scuffles between Gardaí and Reclaim the Streets demonstrators.[42] One Garda in the footage was later convicted of common assault, while several other Gardaí were acquitted.

In 2014, a debate arose relating to alleged abuse of process in cancelling penalty points (for traffic offences), and a subsequent controversy resulted in a number of resignations.[43]

Allegations involving cross-border policing and collusion with the IRA

Former head of intelligence of the Provisional IRA, Kieran Conway claimed that in 1974 the IRA were tipped-off by "high-placed figures" within the Gardaí about a planned RUC Special Branch raid, which was intended to capture members of the IRA command. Conway said "We had contacts in the law offices of the state and contacts in the upper echelons of the guards". Asked if this was just a one-off example of individual Gardaí colluding with the IRA, Conway claimed: "It wasn't just in 1974 and it wasn't just concentrated in border areas like Dundalk, it was some individuals but it was more widespread."[44]

Following a recommendation from the Cory Collusion Inquiry, the Smithwick Tribunal investigated allegations of collusion following the 1989 killing of two Royal Ulster Constabulary officers by the Provisional IRA as they returned from a meeting with the Gardaí. The tribunal's report was published in December 2013,[45][46] and noted that, although there was no "smoking gun", Judge Smithwick was "satisfied there was collusion in the murders" and that "evidence points to the fact that there was someone within the Garda station assisting the IRA". The report was also critical of two earlier Garda investigations into the murders, which it described as "inadequate". Irish Justice Minister Alan Shatter apologised "without reservation" for the failings identified in the report.[47][48] Martin Callinan, Garda Chief, stated that the notion of Garda/IRA collusion was "horrifying", and the Taoiseach, Enda Kenny, declared the report's conclusions to be "shocking".[49]

The family of Eddie Fullerton, a Buncrana Sinn Féin councillor killed in 1991 by members of the Ulster Defence Association, criticised the subsequent Garda investigation,[50][51] and in 2006, the then Minister for Justice considered a public inquiry into the case.[52]

Operations around the Corrib Gas Project

Protests at the proposed Royal Dutch Shell Corrib gas refinery near Erris, County Mayo saw large Garda operations with up to 200 Gardaí involved.[53] By September 2008, the cost of the operation was €10 million, and by January 2009 estimated to have cost €13.5 million.[54] Some outlets compared this to the €20 million budgeted for operations targeting organised crime.[55] A section of road used by the protesters was allegedly dubbed "the Golden Mile" by Gardaí because of overtime opportunities.[56] Complaints were made about Garda handling of the protests[57] and several TDs criticised the handling of the situation.[58]

Reform initiatives

Arising from some of the above incidents, the Garda Síochána underwent a number of reform initiatives in the early 21st century. The Morris Tribunal in particular recommended major changes to the organisation's management, discipline, promotion and accountability arrangements. Many of these recommendations were subsequently implemented under the Garda Síochána Act 2005.

The Tribunal has been staggered by the amount of indiscipline and insubordination it has found in the Garda force. There is a small, but disproportionately influential, core of mischief-making members who will not obey orders, who will not follow procedures, who will not tell the truth and who have no respect for their officers

It was also stated by the tribunal chairman, Justice Morris, that the code of discipline was extremely complex and, at times, "cynically manipulated" to promote indiscipline across the force. Judicial reviews, for example, were cited as a means for delaying disciplinary action.

The fall-out from the Morris Tribunal was considerable. While fifteen members of the force were sacked between 2001 and 2006, and a further 42 resigned in lieu of dismissal in the same period, Commissioner Conroy stated that he was constrained in the responses available to deal with members whose misbehaviour is cited in public inquiries.[60]

New procedures and code of discipline

With strong support from opposition parties, and reflecting widespread political consensus, the Minister for Justice responded to many of these issues by announcing a new draft code of discipline on 17 August 2006. The new streamlined code[61] introduced new procedures to enable the Commissioner to summarily dismiss a Garda alleged to have brought the force into disrepute, abandoned duties, compromised the security of the State or unjustifiably infringed the rights of other persons.

In addition, a four member "non-officer management advisory team" was appointed in August 2006 to advise on implementing change options and addressing management and leadership challenges facing the Gardaí. The advisers were also mandated to promote a culture of performance management, succession planning, recruitment of non-officers with specialist expertise, and improved training. The advisory team included Senator Maurice Hayes, Emer Daly (former director of strategic planning and risk management at Axa Insurance), Maurice Keane (former group chief executive at Bank of Ireland), Michael Flahive (Assistant Secretary at the Department of Justice and Dr Michael Mulreany (assistant director general at the Institute of Public Administration).

Enhanced non-officer support

Clerical and administrative support has been significantly enhanced in recent times. In the two-year period from December 2006 to December 2008 whole-time equivalent non-officer staffing levels were increased by over 60%, from under 1,300 to approximately 2,100, in furtherance of official policies to release more desk-bound Gardaí for operational duties and to bring the level of general support in line with international norms. A new tier of middle and senior non-officer management has also been introduced in a range of administrative and technical/professional support areas. A Chief Administrative Officer at Deputy Commissioner level was appointed in October 2007 to oversee many of these key support functions.

Garda Inspectorate

In accordance with Section 115 of the Garda Síochána Act, the Garda Síochána Inspectorate consists of three members who are appointed by the Irish Government. The functions of the Inspectorate, inter alia, are as follows:

- Carry out, at the request or with the consent of the Minister, inspections or inquiries in relation to any particular aspects of the operation and administration of the Garda Síochána,

- Submit to the Minister (1) a report on those inspections or inquiries, and (2) if required by the Minister, a report on the operation and administration of the Garda Síochána during a specified period and on any significant developments in that regard during that period, and any such reports must contain recommendations for any action the Inspectorate considers necessary.

- provide advice to the Minister with regard to best policing practice.

The first Chief Inspector (since July 2006), is former Commissioner of Boston Police, Kathleen M. O'Toole. She reports directly to the Minister for Justice and Equality.

From 2006 to 2009, O'Toole was supported by two other inspectors, Robert Olsen and Gwen M. Boniface. Olsen was Chief of Police for 8 years of the Minneapolis Police Department. Boniface is a former Commissioner of the Ontario Provincial Police, and was one of 3 female police commissioners in Canada when appointed in May 1998. She suggested that rank and file Gardaí were not equipped to perform their duties or protect themselves properly. She also suggested that routine arming may become a reality but dismissed the suggestion that this was currently being considered.

Garda Síochána Ombudsman Commission

Over 2000 complaints were made against the organisation in 2009.[32] The Garda Commissioner referred over 100 incidents where the conduct of a garda resulted in death or serious injury to the Ombudsman for investigation. Also newly instrumented, the Garda Síochána Ombudsman Commission (referred to colloquially as the Garda Ombudsman or simply abbreviated to GSOC) replaces the earlier system of complaints (the Garda Síochána Complaints Board). Becoming fully operational on 9 May 2007, the Commission is empowered to:

- Directly and independently investigate complaints against members of the Garda Síochána

- Investigate any matter, even where no complaint has been made, where it appears that a Garda may have committed an offence or behaved in a way that justified disciplinary proceedings

- Investigate any practise, policy or procedure of the Garda Síochána with a view to reducing the incidence of related complaints

The members of the Garda Ombudsman Commission are: Dermot Gallagher (Chairman; former Secretary General at the Department of Foreign Affairs), Carmel Foley (former Director of Consumer Affairs), and Conor Brady (former editor of The Irish Times and author of a book on the history of the Gardaí). The Commission's first chairman was Kevin Haugh (a High Court Judge) who died in early 2009, shortly before his term of office was to conclude.[62]

Policing Authority

In the first week of November 2014, Minister for Justice Frances Fitzgerald obtained the approval of the Irish Cabinet for the General Scheme[63] of the Garda Síochána (Amendment) Bill 2014, intended to create a new independent policing authority, in what she described as the 'most far-reaching reform’ of the Garda Síochána since the State was founded in 1922.[64] State security will remain the responsibility of the Minister and will be outside the remit of the Authority.[65] On 13 November 2014, she announced that the chairperson-designate of the new authority would be outgoing Revenue Commissioners chairperson Josephine Feehily.[66]

Public attitudes to An Garda Síochána

The Garda Public Attitudes Survey 2008 found that 81% of respondents were satisfied with the Gardaí, although 72% believed the service needed improvement. 91% agreed that their local Gardaí were approachable.

The survey also found that 8% of people believed a Garda has acted unacceptably towards them; this rate was highest in Dublin South Central at 14%, lowest in Mayo at 2%. The most common complaint was of Gardaí being disrespectful or impolite.[67]

Garda Band

The Garda Band is a public relations branch of the Garda Síochána, and was formed shortly after the foundation of the force. It gave its first public performance on Dún Laoghaire Pier on Easter Monday, 1923. The first Bandmaster was Superintendent D.J. Delaney and he formed a céilí and pipe band within the Garda Band. In 1938, the Dublin Metropolitan Garda Band (based at Kevin Street) and the Garda Band amalgamated and were based at the Garda Headquarters in Phoenix Park.

The band was disbanded in 1965. However to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the Garda Síochána it was reformed in 1972.

Besides providing music for official Garda functions (such as Graduation Ceremonies at the Garda College) the band undertakes a community orientated programme each year performing at schools, festivals and sporting events. It has a long association with Lansdowne Road for Rugby union and Soccer Internationals, as well as Croke Park and the G.A.A., the St. Patrick's Day Parade in Dublin and the Rose of Tralee Festival.

In 1964 the band toured the United States and Canada under Superintendent J. Moloney. [68]

References

- ↑ McNiffe, Liam (1997). A History of the Garda Síochána. Dublin: Wolfhound Press. p. 11. ISBN 0863275818.

The Provisional Government of the Irish Free State set up a committee to orgnise a new police force. The committee first met in the Gresham Hotel, Dublin, on Thursday, 9 February 1922 ... ... ...The first recruit was officially attested on 21 February 1922 and he had been joined by ninety-eight others by the end of that month

- ↑ http://www.budget.gov.ie/Budgets/2015/Documents/Part%20IV%20Estimates%20for%20Public%20Services%202015.pdf

- ↑ Dolan, Terence Patrick (2004). A Dictionary of Hiberno English: the Irish use of English. Gill & Macmillan Ltd. p. 103. ISBN 0-7171-3535-7.

- ↑ "Short History of An Garda Siochana". Garda Síochána. Archived from the original on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 17 December 2006.

the Garda Síochána (meaning in English: 'The Guardians of the Peace')

- ↑ Frank A. Biletz (2013). Historical Dictionary of Ireland. Historical Dictionaries of Europe. Scarecrow Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780810870918. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

Garda Siochana (Guardians of the Peace). The national Police force of the Irish Republic. .... In 1925, the force was renamed the Garda Siochana na hEireann ("Guard of the Peace of Ireland") ... Popularly called "the guards", the force is divided into six geographical regions: ...

- ↑ "Garda Titles". Dáil Éireann. Volume 404. 5 February 1991

- ↑ https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2014-11-04a.1248&s=%22Each+rank%22#g1250.r

- ↑ "First Garda Reserve members graduate". RTÉ News (RTÉ). 15 December 2006. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- ↑ Mike Dwane. "Gardai 'had to pepper spray' disgruntled bidder at auction". Limerick Leader. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Garvin, Tom (2005). 1922: The Birth of Irish Democracy (3rd ed.). Gill and Macmillan. p. 111. ISBN 0-312-16477-7.

- ↑ Anne Sheridan (3 September 2008). "New armed garda unit deployed in Limerick". Limerick Leader. Retrieved 4 May 2009.

- ↑ "Garda College Yearbook listing weapons training on page 66" (PDF).

- ↑ O'Keeffe, Cormac (20 November 2014). "The problems of trying to get policing and national security to walk the line". The Irish Examiner. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Griffin, Dan (21 November 2014). "Ministerial transport costs more than €14m since 2011". The Irish Times. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Williams, Paul; Sheehan, Fionnan; O'Connor, Niall (21 November 2014). "Armed gardai to 'shadow' ministers amid safety fears". Irish Independent. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Williams, Paul; Sheehan, Fionnan; O'Connor, Niall (18 November 2014). "Beefed up security for ministers as family water bills now down to €160". Irish Independent. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ "Ministerial Transport cuts and staffing reductions". merrionstreet.ie. Irish Government.

- ↑ Brady, Tom (17 April 2013). "ERU on alert for G8 terrorist threat". Irish Independent. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ↑ McNiffe, Liam (1997). A History of the Garda Síochána. Dublin: Wolfhound Press. p. 24. ISBN 0863275818.

On 17 August 1922 three small companies of the Civic Guard from Newbridge took a special train to Kingsbridge from where they marched to Dame Street and halted in front of the gates of Dublin Castle. Led by Collins and Staines, they marched in, and the last of the British army and the RIC marched out

- ↑ "Garda Síochána (Temporary Provisions) Act 1923". Archived from the original on 8 February 2007. Retrieved 29 March 2006.

- ↑ Garda.ie – History of the Scott Medal

- ↑ "Murdered garda hero honoured". Encyclopedia of Things. Irish Examiner. Retrieved 29 March 2006.

- ↑ "Garda issues". Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ Ireland in the Twentieth Century, Tim Pat Coogan

- ↑ "Garda Síochána Act 1979". Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- ↑ Cormac O'Keeffe (26 November 2014). "Whistleblower welcomes O’Sullivan appointment as Garda Commissioner". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

Her appointment means the bulk of top justice posts are headed by women, including the Minister for Justice, the chair of the new Policing Authority, the Chief Justice, the Director of Public Prosecutions, the Attorney General, and the Chief State Solicitor.

- ↑ Analysis: McDowell not for turning on Garda reserve, 26 February 2006, The Sunday Business Post

- ↑ "History of the Army Reserve". The Defense Forces. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ↑ Freedom of Information Request Number F-2008-05327. Lateral Entry into PSNI

- ↑ "Annual Report 2005". Garda Síochána Complaints Board.

- ↑ "More than 1,000 complaints against gardaí in year". www.breakingnews.ie. 15 May 2006. Retrieved 15 May 2006.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "2,000 complaints made to Garda Ombudsman". RTÉ. 28 May 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2010.

- ↑ "Oireachtas review recommends sweeping Garda reforms". Irish Times. 3 October 2014.

- ↑ "Green Party calls on Gardaí to rethink its ban on Sikh turban". Irish Independent. 22 August 2007.

- ↑ "Ferns Report". Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ Report by Commission of Investigation into Catholic Archdiocese of Dublin, part 1, sections 1.92 through 1.96

- ↑ Report by Commission of Investigation into Catholic Archdiocese of Dublin, part 1, sections 1.92

- ↑ Report by Commission of Investigation into Catholic Archdiocese of Dublin, part 1, sections 1.93

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Garda apologises for failures, Ciara O'Brien, The Irish Times, 26 November 2009

- ↑ Gardaí to examine abuse report findings, RTE News, 27 November 2009.

- ↑ George Birmingham, SC (2004), Report of The Commission of Investigation(Dean Lyons Case) (PDF)

- ↑ "Garda Goes Berserk". www.indymedia.ie. Retrieved 29 March 2006.

- ↑ "Timeline of events leading to Shatter resignation". RTÉ News. 7 May 2014.

- ↑ "Irish police colluded with IRA during Troubles, says former IRA member". The Guardian. December 2014.

- ↑ Report of the Tribunal of Inquiry into suggestions that members of An Garda Siochana or other employees of the State colluded in the fatal shooting of RUC Chief Superintendent Harry Breen and RUC Superintendent Robert Buchanan on the 20th March 1989 (PDF) (Report). Smithwick Tribunal. December 2013.

- ↑ "Acting Clerk of Dáil confirms publication of report from Judge Peter Smithwick". Houses of Oireachtas (Press Release). December 2013.

- ↑ "Smithwick: Collusion in Bob Buchanan and Harry Breen murders". BBC News. 3 December 2013.

- ↑ "Irish police colluded in murders of RUC officers Harry Breen and Bob Buchanan, report finds". Telegraph Newspaper date=3 December 2013.

- ↑ "BBC report on Smithwick Tribunal report". BBC News. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ "Seanad hears tribute to Eddie Fullerton". Inishowen News. 22 February 2008. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Mc Daid, Kieran (26 May 2006). "Home»Today's Stories Inquiry urged into murder of councillor". Irish Exaniner. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ "McDowell considering inquiry into Eddie Fullerton murder". Breaking News. 21 June 2006. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ "Garda operation at site of Corrib gas terminal". RTÉ News. 3 October 2006.

- ↑ "Corrib policing bill tops €1m in month". Breaking News. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "Garda gets Interpol aid on Corrib protesters". The Irish Times. 9 September 2008.

- ↑ "New gas pipeline route likely to be as controversial as original". The Irish Times. 29 April 2008. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011.

- ↑ "Complaints against 20 Gardaí in Corrib row". Western People. 9 May 2007. Archived from the original on 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "TDs criticise Garda response to 'Shell to Sea' protests". BreakingNews.ie. 21 November 2006. Archived from the original on 16 September 2009.

- ↑ "Report 5, Arrest and Detention of 7 persons at Burnfoot, County Donegal on May 23, 1998 and the Investigation relating to same – Conclusions and Recommendations: The Danger of Indiscipline" (PDF). Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform. 17 August 2006. p. 254.

- ↑ "Insubordination not widespread, says Garda chief". The Irish Times. 2 September 2006.

- ↑ "Statement by the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform on the publication of the 3rd, 4th and 5th Reports of the Morris Tribunal". Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform. 17 August 2006.

- ↑ http://gardaombudsman.ie/gsoc-garda-ombudsman-about-us.htm#GSOCGardaOmbudsmanWhoWeAre

- ↑ "General Scheme - Garda Síochána Amendment Bill" (PDF). Department of Justice, Ireland. November 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Stephen Collins (7 November 2014). "New Bill provides for set up of independent policing authority". Irish Times. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

Fitzgerald says move ‘most far-reaching reform’ of Garda since foundation of State ... The general scheme of a Bill providing for the establishment of the new independent policing authority has been published by Minister for Justice Frances Fitzgerald.The Minister received the approval of the Cabinet this week for the heads of the Garda Síochána (Amendment) Bill 2014 which will pave the way for creation of the authority.

- ↑ Vicky Conway (10 November 2014). "Ireland’s Policing Authority". Human Rights in Ireland. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

Outside of it’s remit is security, a shorthand for state security which is defined as:[terrorism] [terrorist offences within the meaning of the Criminal Justice (Terrorist Offences) Act 2005]; espionage; sabotage; acts intended to subvert or undermine parliamentary democracy or the institutions of the State, but not including lawful advocacy, protest or dissent, unless carried on in conjunction with any of those acts; and acts of foreign interference; If a dispute arises as to whether something is a security matter, the Minister will make the decision. There’s a pretty clear divide in the Scheme of the Bill; when something relates to security it falls to the Minister, when it relates to policing it falls to the Authority.

- ↑ Tom Brady (13 November 2014). "Government appoints outgoing Revenue Commissioners chairman head of new independent policing authority". Irish Independent. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

Justice Minister Frances Fitzgerald announced this afternoon that Ms Josephine Feehily would “bring a wealth of experience and competences” to her new role.She will be chairperson-designate until legislation establishing the authority has been fully enacted.

- ↑ "Most happy with gardaí but want improvement – survey". The Irish Times. 12 October 2008.

- ↑ An Irishman’s Diary on how the Garda Band took the US by storm ‘Ireland On Parade’ – a tour to remember Ruraidh Conion O'Reilly Irish Times November 13, 2014 http://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/an-irishman-s-diary-on-how-the-garda-band-took-the-us-by-storm-1.1998163

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Garda Síochána. |

- Official website

- Garda Representative Association

- Garda Síochána Ombudsman Commission

- Garda Headquarters, Phoenix Park, Dublin

- Association of Garda Sergeants and Inspectors

- Garda Síochána mission statement on community policing

- Morris Tribunal

- Garda Síochána Act 2005

- Garda Roll of Honour

- An Garda Síochána at the Wayback Machine (archived 7 December 1998)

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||