Gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase

Gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase (also known as BBOX, GBBH or γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the BBOX1 gene.[1][2] Gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase catalyses the formation of L-carnitine from gamma-butyrobetaine, the last step in the L-carnitine biosynthesis pathway.[3] Carnitine is essential for the transport of activated fatty acids across the mitochondrial membrane during mitochondrial beta oxidation.[2] In humans, gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase can be found in kidney (high), liver (moderate), and brain (very low).[1][4] BBOX1 has recently been identified as a potential cancer gene on the basis of a large-scale microarray data analysis.[5]

Reaction

| gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC number | 1.14.11.1 | ||||||||

| CAS number | 9045-31-2 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / EGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The following reaction is catalyzed by gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase:

- 4-trimethylammoniobutanoate (γ-butyrobetaine) + 2-oxoglutarate + O2

3-hydroxy-4-trimethylammoniobutanoate (L-carnitine) + succinate + CO2

3-hydroxy-4-trimethylammoniobutanoate (L-carnitine) + succinate + CO2

The three substrates of this enzyme are 4-trimethylammoniobutanoate (γ-butyrobetaine), 2-oxoglutarate, and O2,[6] whereas its three products are 3-hydroxy-4-trimethylammoniobutanoate (L-carnitine), succinate, and carbon dioxide.

This enzyme belongs to the family of oxidoreductases, specifically those acting on paired donors, with O2 as oxidant and incorporation or reduction of oxygen. The oxygen incorporated need not be derived from O2 with 2-oxoglutarate as one donor, and incorporation of one atom of oxygen into each donor. This enzyme participates in lysine degradation. Iron is a cofactor for gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase. Similar to many other 2OG oxygenases, the activity of gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase can be stimulated by reducing agents such as ascorbate and glutathione.[7][8][9][10] The catalytic activity of gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase can be stimulated with different metal ions, especially potassium ions.[11]

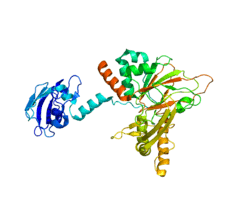

Both the apo (PDB id: 3N6W)[12] and the holo (PDB id: 3O2G)[13] structures of gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase have been solved, demonstrating an induced fit mechanism may contribute to the catalytic activity of gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase.

Gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase is promiscus in substrate selectivity and it processes a number of modified substrates, including the natural catalytic products L-carnitine and D-carnitine, forming 3-dehydrocarnitine and trimethylaminoacetone.[13][14] Gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase also catalyses the oxidation of mildronate[15] to form multiple products including malonic acid semialdehyde, dimethylamine, formaldehyde and (1-methylimidazolidin-4-yl)acetic acid, which is proposed to be formed via a Stevens rearrangement mechanism.[16][17] Gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase is unique among other human 2OG oxygenases that it catalyses both hydroxylation (e.g.: L-carnitine), demethylation (e.g.: formaldehyde) and C-C bond formation (e.g.: (1-methylimidazolidin-4-yl)acetic acid).[18]

Inhibition

Gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase is an inhibition target for 3-(2,2,2-trimethylhydraziniumyl)propionate (mildronate, also known as THP, MET-88, Meldonium or Quarterine). Mildronate is clinically used for the treatments of angina and myocardial infarction.[19][20][21] Some studies suggested that mildronate may also be beneficial for the treatment of neurological disorder,[22][23] diabetes,[24] and seizures and alcohol intoxication.[25] Mildronate is currently manufactured and marketed by Grindeks, a pharmaceutical company based in Latvia. To date, at least five clinical trial reports were published in peer-reviewed journals documenting the efficacy and safety of mildronate on the treatments of angina, stroke and chronic heart failure.[26][27][28][29][30]

Mildronate has a similar structure to the natural substrate gamma-butyrobetaine, with a NH group replacing the CH2 of gamma-butyrobetaine at the C-4 position. A crystal structure of mldronate in complex with gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase was published, and it suggests mildronate bind to gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase in exactly the same way as gamma-butyrobetaine (PDB id: 3MS5).[31] To date, most enzyme inhibitors for human 2OG oxygenases bind to the cosubstrate 2OG binding site; mildronate is a rare example of a non-peptidyl substrate mimic inhibitor.[32] Although initial reports suggested mildronate is a non-competitive and non-hydroxylatable analogue of gamma-butyrobetaine,[33] further studies have identified mildronate is indeed a substrate for gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase.[13][16][34]

Similar to other 2OG oxygenases, gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase can be inhibited by 2OG mimics and aromatic inhibitors such as pyridine 2,4-dicarboxylate.[35] Other reported gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase inhibitors include cyclopropyl-substituted gamma-butyrobetaines[36] and 3-(2,2-dimethylcyclopropyl)propanoic acid, which is a mechanism-based enzyme inhibitor.[37]

Assay

Several in vitro biochemical assays have been applied to monitor the catalytic activity of gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase. Early methods have mainly focused on the use of radiolabeled compounds, including 14C-labelled gamma-butyrobetaine[38] and 14C-labelled 2OG.[39] Enzyme-coupled method have also been applied to detect carnitine formation, by using the enzyme carnitine acetyltransferase and 14C-labelled acetyl-coenzyme A to give labelled acetylcarnitine for detection. Using this method, it is possible to detect carnitine concentration down to the pico-molar range.[40][41][42] Other analytical methods including mass spectrometry and NMR have also been applied,[13] and they are in particularly useful for the study of the coupling ratio between 2OG oxidation and substrate formation, and for the characterisation of unknown enzymatic products.[14] However, these methods are often not suitable for high-throughput screening and require expensive instrumentation. A potentially high-throughput fluorescence-based assay has also been proposed by using a fluorinated-gamma-butyrobetaine analogue.[43] The fluoride ions released as a result of gamma-butyrobetaine dioxygenase catalyses can be detected by using chemosensors such as protected fluorescein.[44]

See also

- Carnitine

- Mildronate

- Carnitine biosynthesis

- Beta Oxidation

- Fatty acid metabolism

- Stevens rearrangement

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Vaz FM, van Gool S, Ofman R, Ijlst L, Wanders RJ (Nov 1998). "Carnitine biosynthesis: identification of the cDNA encoding human gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase". Biochem Biophys Res Commun 250 (2): 506–10. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1998.9343. PMID 9753662.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Entrez Gene: BBOX1 butyrobetaine (gamma), 2-oxoglutarate dioxygenase (gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase) 1".

- ↑ Paul HS, Sekas G, Adibi SA (1992). "Carnitine biosynthesis in hepatic peroxisomes. Demonstration of gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase activity". Eur. J. Biochem. 203 (3): 599–605. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16589.x. PMID 1735445.

- ↑ Lindstedt G, Lindstedt S, Nordin I (1983). "Gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase in human kidney". Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 42 (6): 477–85. doi:10.3109/00365518209168117. PMID 7156861.

- ↑ Dawany NB, Dampier WN, Tozeren A (June 2011). "Large-scale integration of microarray data reveals genes and pathways common to multiple cancer types". Int. J. Cancer 128 (12): 2881–91. doi:10.1002/ijc.25854. PMID 21165954.

- ↑ Lindstedt G, Lindstedt S (1970). "Cofactor requirements of gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase from rat liver". J. Biol. Chem. 245 (16): 4178–86. PMID 4396068.

- ↑ Rebouche CJ (1992). "Ascorbic acid and carnitine biosynthesis". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 54 (6 Suppl): 1147S–1152S. PMID 1962562.

- ↑ Nelson PJ, Pruitt RE, Henderson LL, Jenness R, Henderson LM (January 1981). "Effect of ascorbic acid deficiency on the in vivo synthesis of carnitine". Biochim. Biophys. Acta 672 (1): 123–7. doi:10.1016/0304-4165(81)90286-5. PMID 6783120.

- ↑ Rebouche C J (1991). "Ascorbic acid and carnitine biosynthesis". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 54 (6): 1147S–1152S. PMID 1962562.

- ↑ Furusawa H, Sato Y, Tanaka Y, Inai Y, Amano A, Iwama M, Kondo Y, Handa S, Murata A, Nishikimi M, Goto S, Maruyama N, Takahashi R, Ishigami A (September 2008). "Vitamin C is not essential for carnitine biosynthesis in vivo: verification in vitamin C-depleted senescence marker protein-30/gluconolactonase knockout mice". Biol. Pharm. Bull. 31 (9): 1673–9. doi:10.1248/bpb.31.1673. PMID 18758058.

- ↑ Wehbie RS, Punekar NS, Lardy HA (March 1988). "Rat liver gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase catalyzed reaction: influence of potassium, substrates, and substrate analogues on hydroxylation and decarboxylation". Biochemistry 27 (6): 2222–8. doi:10.1021/bi00406a062. PMID 3378057.

- ↑ PDB 3N6W;Tars K, Rumnieks J, Zeltins A, Kazaks A, Kotelovica S, Leonciks A, Sharipo J, Viksna A, Kuka J, Liepinsh E, Dambrova M (August 2010). "Crystal structure of human gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 398 (4): 634–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.121. PMID 20599753.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 PDB 3O2G; Leung IKH, Krojer TJ, Kochan GT, Henry L, von Delft F, Claridge TDW, Oppermann U, McDonough MA, Schofield CJ (December 2010). "Structural and mechanistic studies on γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase". Chem. Biol. 17 (12): 1316–24. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.09.016. PMID 21168767.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Fujimori DG (December 2010). "A novel enzymatic rearrangement". Chem. Biol. 17 (12): 1269–70. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.12.003. PMID 21168760.

- ↑ Simkhovich BZ, Shutenko ZV, Meirena DV, Khagi KB, Mezapuķe RJ, Molodchina TN, Kalviņs IJ, Lukevics E (January 1988). "3-(2,2,2-Trimethylhydrazinium)propionate (THP)--a novel gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase inhibitor with cardioprotective properties". Biochem. Pharmacol. 37 (2): 195–202. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(88)90717-4. PMID 3342076.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Henry L, Leung IKH, Claridge TDW, Schofield CJ (Aug 2012). "γ-Butyrobetaine hydroxylase catalyses a Stevens type rearrangement". Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 22 (15): 4975–4978. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.06.024. PMID 22765904.

- ↑ Stevens TS, Creighton EM, Gordon AB, MacNicol M (1928). "CCCCXXIII.—Degradation of quaternary ammonium salts. Part I". J. Chem. Soc.: 3193–3197. doi:10.1039/JR9280003193.

- ↑ Loenarz C, Schofield CJ (March 2008). "Expanding chemical biology of 2-oxoglutarate oxygenases". Nat. Chem. Biol. 4 (3): 152–6. doi:10.1038/nchembio0308-152. PMID 18277970.

- ↑ Sesti C, Simkhovich BZ, Kalvinsh I, Kloner RA (March 2006). "Mildronate, a novel fatty acid oxidation inhibitor and antianginal agent, reduces myocardial infarct size without affecting hemodynamics". J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 47 (3): 493–9. doi:10.1097/01.fjc.0000211732.76668.d2. PMID 16633095.

- ↑ Liepinsh E, Vilskersts R, Loca D, Kirjanova O, Pugovichs O, Kalvinsh I, Dambrova M (December 2006). "Mildronate, an inhibitor of carnitine biosynthesis, induces an increase in gamma-butyrobetaine contents and cardioprotection in isolated rat heart infarction". J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 48 (6): 314–9. doi:10.1097/01.fjc.0000250077.07702.23. PMID 17204911.

- ↑ Hayashi Y, Kirimoto T, Asaka N, Nakano M, Tajima K, Miyake H, Matsuura N (May 2000). "Beneficial effects of MET-88, a gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase inhibitor in rats with heart failure following myocardial infarction". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 395 (3): 217–24. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(00)00098-4. PMID 10812052.

- ↑ Sjakste N, Gutcaits A, Kalvinsh I (2005). "Mildronate: an antiischemic drug for neurological indications". CNS Drug Rev 11 (2): 151–68. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2005.tb00267.x. PMID 16007237.

- ↑ Pupure J, Isajevs S, Skapare E, Rumaks J, Svirskis S, Svirina D, Kalvinsh I, Klusa V (February 2010). "Neuroprotective properties of mildronate, a mitochondria-targeted small molecule". Neurosci. Lett. 470 (2): 100–5. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2009.12.055. PMID 20036318.

- ↑ Liepinsh E, Skapare E, Svalbe B, Makrecka M, Cirule H, Dambrova M (May 2011). "Anti-diabetic effects of mildronate alone or in combination with metformin in obese Zucker rats". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 658 (2-3): 277–83. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.02.019. PMID 21371472.

- ↑ Zvejniece L, Svalbe B, Makrecka M, Liepinsh E, Kalvinsh I, Dambrova M (September 2010). "Mildronate exerts acute anticonvulsant and antihypnotic effects". Behav Pharmacol 21 (5-6): 548–55. doi:10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833d5a59. PMID 20661137.

- ↑ Dzerve V, Matisone D, Kukulis I, Romanova J, Putane L, Grabauskiene˙V, Skarda I, Berzina D, Strautmanis J (2005). "Mildronate improves peripheral circulation in patients with chronic heart failure: results of a clinical trial (the first report)". Semin Cardiol 11 (2): 56–64. ISSN 1648-7966.

- ↑ Vitols A, Voita D, Dzerve V (2008). "Mildronate improves carotid baroreceptor reflex function in patients with chronic heart failure". Semin Cardiovasc Med 13: 6.

- ↑ Dzerve V, Matisone D, Pozdnyakov Y, Oganov R (2010). "Mildronate improves the exercise tolerance in patients with stable angina: results of a long term clinical trial". Semin Cardiovasc Med 16: 3.

- ↑ Dzerve V, MILSS I Study Group (2011). "A Dose-Dependent Improvement in Exercise Tolerance in Patients With Stable Angina Treated With Mildronate: A Clinical Trial "MILSS I"". Medicina (Kaunas) 47 (10): 544–51. PMID 22186118.

- ↑ Zhu Y, Zhang G, Zhao J, Li D, Yan X, Liu J, Liu X, Zhao H, Xia J, Zhang X, Li Z, Zhang B, Guo Z, Feng L, Zhang Z, Qu F, Zhao, G (2013). "Efficacy and safety of mildronate for acute ischemic stroke: a randomized, double-blind, active-controlled phase II multicenter trial". Clin Drug Investig. doi:10.1007/s40261-013-0121-x.

- ↑ PDB 3MS5

- ↑ Rose NR, McDonough MA, King ON, Kawamura A, Schofield CJ (August 2011). "Inhibition of 2-oxoglutarate dependent oxygenases". Chem Soc Rev 40 (8): 4364–97. doi:10.1039/c0cs00203h. PMID 21390379.

- ↑ Galland S, Le Borgne F, Guyonnet D, Clouet P, Demarquoy J (January 1998). "Purification and characterization of the rat liver gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase". Mol. Cell. Biochem. 178 (1–2): 163–8. doi:10.1023/A:1006849713407. PMID 9546596.

- ↑ Spaniol M, Brooks H, Auer L, Zimmermann A, Solioz M, Stieger B, Krähenbühl S (March 2001). "Development and characterization of an animal model of carnitine deficiency". Eur. J. Biochem. 268 (6): 1876–87. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02065.x. PMID 11248709.

- ↑ Ng SF, Hanauske-Abel HM, Englard S (January 1991). "Cosubstrate binding site of Pseudomonas sp. AK1 gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase. Interactions with structural analogs of alpha-ketoglutarate". J. Biol. Chem. 266 (3): 1526–33. PMID 1988434.

- ↑ Petter RC, Banerjee S, Englard S (1990). "Inhibition of γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase by cyclopropyl-substituted γ-butyrobetaines". J. Org. Chem. 55 (10): 3088–3097. doi:10.1021/jo00297a025.

- ↑ Ziering DL, Pascal Jr RA (1990). "Mechanism-based inhibition of bacterial γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112 (2): 834–838. doi:10.1021/ja00158a051.

- ↑ Lindstedt G, Lindstedt S, Tofft S (1970). "γ-Butyrobetaine Hydroxylase from Pseudomonas sp AK 1". Biochemistry 9 (22): 4336–4342. doi:10.1021/bi00824a014.

- ↑ Lindstedt G, Lindstedt S, Nordin I (1977). "Purification and properties of γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase from Pseudomonas species AK 1". Biochemistry 16 (10): 2181–2188. doi:10.1021/bi00629a022.

- ↑ Cederblad C, Lindstedt S (1972). "A method for the determination of carnitine in the picomole range". Clin. Chim. Acta 37: 235–243. doi:10.1016/0009-8981(72)90438-X.

- ↑ Böhmer T, Rydning A, Solberg HE (1974). "Carnitine levels in human serum in health and disease". Clin. Chim. Acta 57 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1016/0009-8981(74)90177-6.

- ↑ Parvin R, Pande SV (1976). "Microdetermination of (−)carnitine and carnitine acetyltransferase activity". Anal. Biochem. 79 (1-2): 190–201. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(77)90393-1.

- ↑ Rydzik AM, Leung IKH, Kochan GT, Thalhammer A, Oppermann U, Claridge TDW, Schofield CJ (2012). "Development and Application of a Fluoride-Detection-Based Fluorescence Assay for γ-Butyrobetaine Hydroxylase". ChemBioChem 13 (11): 1559–1563. doi:10.1002/cbic.201200256. PMID 22730246.

- ↑ Cametti M, Rissanen K (2009). "Recognition and sensing of fluoride anion". Chem. Commun. (20): 2809–2829. doi:10.1039/B902069A.

Further reading

- Olson AL, Rebouche CJ (1987). "gamma-Butyrobetaine hydroxylase activity is not rate limiting for carnitine biosynthesis in the human infant". J. Nutr. 117 (6): 1024–31. PMID 3110383.

- Lindstedt S, Nordin I (1984). "Multiple forms of gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase (EC 1.14.11.1)". Biochem. J. 223 (1): 119–27. PMC 1144272. PMID 6497835.

- Galland S, Le Borgne F, Bouchard F et al. (1999). "Molecular cloning and characterization of the cDNA encoding the rat liver gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase". Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1441 (1): 85–92. doi:10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00135-3. PMID 10526231.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH et al. (2003). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- Gerhard DS, Wagner L, Feingold EA et al. (2004). "The status, quality, and expansion of the NIH full-length cDNA project: the Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC)". Genome Res. 14 (10B): 2121–7. doi:10.1101/gr.2596504. PMC 528928. PMID 15489334.

- Kimura K, Wakamatsu A, Suzuki Y et al. (2006). "Diversification of transcriptional modulation: large-scale identification and characterization of putative alternative promoters of human genes". Genome Res. 16 (1): 55–65. doi:10.1101/gr.4039406. PMC 1356129. PMID 16344560.

- Rigault C, Le Borgne F, Demarquoy J (2007). "Genomic structure, alternative maturation and tissue expression of the human BBOX1 gene". Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761 (12): 1469–81. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.09.014. PMID 17110165.