Gaeltacht

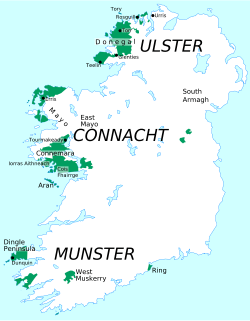

Gaeltacht or Gaedhealtacht (/ˈɡeɪltəxt/; Irish pronunciation: [ˈɡeːl̪ˠt̪ˠəxt̪ˠ] or [ˈɡeːl̪ˠhəxt̪ˠ]; plural Gaeltachtaí) is an Irish-language word used to denote any primarily Irish-speaking region.

In Ireland, the term refers individually to any, or collectively to all, of the districts where the government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.[1] These districts were first officially recognised during the early years of the Irish Free State, following the Gaelic Revival, as part of a government policy aimed at restoring the Irish language.[2] It is now recognised that the Gaeltacht is threatened by serious language decline.[3]

Boundaries

The boundaries of the Gaeltacht have always included a high percentage of resident English speakers. This was so even in 1926, when the official Gaeltacht came into being after the report of the first Gaeltacht Commission Coimisiún na Gaeltachta. The exact boundaries were not defined. The quota at the time was 25%+ Irish-speaking, although in many cases Gaeltacht status was accorded to areas that were linguistically weaker than this. The Irish Free State recognised that there were Irish-speaking or semi-Irish-speaking districts in 15 of its 26 counties.

In the 1950s another Gaeltacht Commission concluded that the Gaeltacht boundaries were ill-defined. It recommended that the Gaeltacht status admittance of an area be based solely on the strength of the language there. The Gaeltacht districts were initially defined precisely in the 1950s, excluding many areas which had witnessed a decline in the language. This left Gaeltacht areas in seven of the state's 26 counties (nominally Donegal, Galway, Mayo, Kerry, Cork, and Waterford). The Gaeltacht boundaries have not officially been altered since then, apart from minor changes:

- The inclusion of An Clochán (Cloghane) and Cé Bhréanainn (Brandon) in County Kerry in 1974;

- The inclusion of a part of West Muskerry in County Cork (although the Irish-speaking population had seriously decreased from what it had been before the 1950s); and

- The inclusion of Baile Ghib (Gibstown) and Ráth Chairn (Rathcarran) in Meath in 1967.

Linguistic crisis in the Gaeltacht

In 2002 the third Coimisiún na Gaeltachta stated in its report[4] that the erosion of Irish was now such that it was only a matter of time before the Gaeltacht disappeared. In some areas Irish had already ceased to be a community language. Even in the strongest Gaeltacht areas, current patterns of bilingualism were leading to the dominance of English. Policies implemented by the State and voluntary groups were having no effect. A new language reinforcement strategy was required, one that had the confidence of the community itself. The Commission recommended, among many other things, that the boundaries of the official Gaeltacht should be redrawn. It also recommended a comprehensive linguistic study to assess the vitality of the Irish language in the remaining Gaeltacht districts.

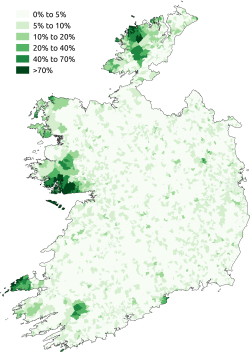

The study was undertaken by Acadamh na hOllscolaíochta Gaeilge (part of the National University of Ireland, Galway), and on 1 November 2007 Staidéar Cuimsitheach Teangeolaíoch ar Úsáid na Gaeilge sa Ghaeltacht ("A Comprehensive Linguistic Study of the Usage of Irish in the Gaeltacht") appeared.[5] Concerning Gaeltacht boundaries, it suggested creating three linguistic zones within the Gaeltacht region:

- A – 67%/+ daily Irish speaking – Irish dominant as community language

- B – 44%–66% daily Irish speaking – English dominant, with large Irish speaking minority

- C – 43%/- daily Irish speaking – English dominant, but with Irish speaking minority much higher than the national average of Irish speaking

The report suggested that Category A districts should be the State's priority in providing services through Irish and development schemes, and that Category C areas showing a further decline in the use of Irish should lose their Gaeltacht status.

Analysis of data from the 2006 Census shows that of the 95,000 people living within the official Gaeltacht, approximately 17,000 belonged to Category A areas, 10,000 to Category B and 17,000 to Category C, leaving about 50,000 in Gaeltacht areas which did not meet the minimum criteria.[6] In response to this situation, the government introduced the Gaeltacht Bill 2012. Its stated aim was to provide for a new definition of boundaries based on language criteria, but it was criticised for doing the opposite of this. Critics drew attention to Section 7 of the Bill, which stated that all areas "currently within the Gaeltacht" would maintain their current Gaeltacht status, irrespective of whether Irish was actually used. This status could only be revoked if the area failed to prepare a language plan (with no necessary relationship to the actual number of speakers).[7] The Bill was also criticised for placing all responsibility for the maintenance of Irish on voluntary organisations, with no increase in resources.[8]

The annual report in 2012 by the Language Commissioner for Irish reinforced these criticisms by emphasising the failure of the State to provide Irish-language services to Irish speakers in the Gaeltacht and elsewhere. The report said that Irish in the Gaeltacht was now at its most fragile and that the State could not expect that Irish would survive as a community language if the State itself kept forcing English on Gaeltacht communities.[9]

An earlier study in 2005 by An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta (the educational council for Gaeltacht and Irish-medium schools which was established in 2002 under the Education Act 1998) said that Gaeltacht schools were facing a crisis and that without support few of them would be teaching through Irish in 20 years' time. This would threaten the future of the Gaeltacht. Parents felt that the educational system cancelled their efforts to pass on Irish as a living language to their children. The study added that a significant number of Gaeltacht schools had switched to teaching through English, and others were wavering.[10]

Northern Ireland

There were areas of Northern Ireland that would have qualified as Gaeltacht districts (in 4 out of its 6 counties) at the time of partition, but the Government of Northern Ireland passed no legislation to ensure this. The language was proscribed in state schools within a decade of partition, and public signs in Irish were effectively banned under laws passed by the Parliament of Northern Ireland, which stated that only English could be used.

In 2001, however, the British government ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Irish (in respect only of Northern Ireland) was specified under Part III of the Charter, giving it a status comparable to that of the Welsh language or Scottish Gaelic. This included undertakings in relation to education, translation of statutes, interaction with public authorities, the use of placenames, media access, support for cultural activities and other matters. Compliance with the state's obligations is assessed periodically by a Committee of Experts of the Council of Europe.[11]

Gaeltachtaí in the Republic of Ireland

Demographics

At the time of the 2006 census of the Republic of Ireland, the population of the Gaeltacht was 91,862,[12] approximately 2.1% of the state's 4,239,848 people, with major concentrations of Irish speakers located in the western counties of Donegal, Mayo, Galway, Kerry, and Cork.[13] There were smaller concentrations in the counties of Waterford in the south and Meath in the east. The Meath Gaeltacht, Ráth Cairn, came about when the government provided a house and 9 hectares (22 acres) for each of 41 families from Connemara and Mayo in the 1930s, in exchange for their original lands. It was not recognised as an official Gaeltacht area until 1967.[14]

The Gaeltacht districts have historically suffered from mass migration.[15] Being at the edge of the island they always had fewer railways and roads, and poorer land to farm. Other influences have been the arrival of non-Irish speaking families, the marginal role of the Irish language in the education system and general pressure from the English-speaking community.[16] There is no evidence that periods of relative prosperity have materially improved the situation of the language.

The following table lists the Gaeltacht areas in which at least 40% of the population speaks Irish on a daily basis. Some areas may contain several villages, e.g. the area Aran Islands consists of the three islands of Inishmore (with Kilronan), Inishmaan and Inisheer.

| County | English name | Irish name | Population | Irish speakers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| County Donegal | Altnapeaste | Alt na Péiste | 188 | 55% |

| Annagry | Anagaire | 2235 | 55% | |

| Arranmore | Árainn Mhór | 529 | 62% | |

| Crovehy | Cró Beithe | 161 | 53% | |

| Cloghan | An Clochán | 514 | 41% | |

| Bloody Foreland | Cnoc Fola | 1326 | 83% | |

| Dunlewey | Dún Lúiche | 695 | 76% | |

| Falcarragh | An Fál Carrach | 2168 | 44% | |

| Fintown | Baile na Finne | 316 | 57% | |

| Gortahork | Gort a' Choirce | 1599 | 81% | |

| Graffy | An Ghrafaidh | 209 | 52% | |

| Gweedore | Gaoth Dobhair | 2651 | 77% | |

| Teelin | Teileann | 726 | 41% | |

| County Mayo | Aughleam | Eachléim | 921 | 46% |

| Carrowteige | Ceathrú Thaidhg | 356 | 64% | |

| Finny | Fionnaithe | 248 | 44% | |

| County Galway | Aran Islands | Oileáin Árann | 1225 | 79% |

| Bothúna | Bothúna | 963 | 74% | |

| Camus | Camus | 367 | 90% | |

| Carna | Carna | 798 | 81% | |

| Carraroe | An Cheathrú Rua | 2294 | 83% | |

| Cornamona | Corr na Móna | 573 | 45% | |

| Furbo | Na Forbacha | 1239 | 43% | |

| Derryrush | Doire Iorrais | 313 | 76% | |

| Glentrasna | Gleann Trasna | 122 | 61% | |

| Inverin | Indreabhán | 1362 | 83% | |

| Kilkieran | Cill Chiaráin | 619 | 87% | |

| Lettermore | Leitir Móir | 875 | 84% | |

| Lettermullen | Leitir Mealláin | 1288 | 89% | |

| Rossaveal | Ros an Mhíl | 1304 | 84% | |

| Rosmuc | Ros Muc | 557 | 87% | |

| Spiddal | An Spidéal | 1357 | 66% | |

| County Kerry | Ballyferriter | Baile an Fheirtéaraigh | 455 | 77% |

| Ballydavid | Baile na nGall | 508 | 75% | |

| Brandon | Cé Bhréannain | 168 | 48% | |

| Kinard | Cinn Aird | 318 | 45% | |

| Cloghane | An Clochán | 273 | 46% | |

| Dunquin | Dún Chaoin | 159 | 72% | |

| Feohanagh | Feothanach | 462 | 78% | |

| Glin | Na Gleannta | 1496 | 44% | |

| Marhin | Márthain | 276 | 56% | |

| Minard | An Mhin Aird | 387 | 53% | |

| Ventry | Ceann Trá | 413 | 59% | |

| County Cork | Ballingeary | Béal Átha an Ghaorthaidh | 542 | 46% |

| Ballyvourney | Baile Bhuirne | 816 | 42% | |

| Cape Clear Island | Oileán Chléire | 125 | 41% | |

| Coolea | Cúil Aodha | 420 | 53% | |

| County Waterford | Ring | An Rinn | 1176 | 51% |

| County Meath | Rathcarne | Ráth Cairn | 401 | 56% |

Cork Gaeltacht

The Cork Gaeltacht (Irish: Gaeltacht [Chontae] Chorcaí)[17] consists of two areas – Múscraí and Oileán Chléire. The Múscraí Gaeltacht has a population of 3,895 people (2,951 Irish speakers)[18] and represents 4% of the total Gaeltacht population. The Cork Gaeltacht encompasses a geographical area of 262 km2 (101 sq mi). This represents 6% of the total Gaeltacht area. The largest Múscraí settlements are the villages of Baile Mhic Íre (Ballymakeera), Baile Bhuirne (Ballyvourney) and Béal Átha an Ghaorthaidh (Ballingeary).

Donegal Gaeltacht

The Donegal (or Tyrconnell) Gaeltacht (Irish: Gaeltacht [Chontae] Dhún na nGall or Gaeltacht Thír Chonaill)[19][20] has a population of 24,744[21] (Census 2011) and represents 25% of the total Gaeltacht population. The Donegal Gaeltacht encompasses a geographical area of 1,502 km2 (580 sq mi). This represents 26% of total Gaeltacht land area. The three parishes of Na Rosa, Gaoth Dobhair and Cloch Cheannfhaola constitute the main centre of population of the Donegal Gaeltacht. There are over 17,132 Irish speakers, 14,500 in areas where it is spoken by 30–100% of the population and 2,500 in areas where it is spoken by less than 30%. In 2006 there were 2 436 people employed in a full-time capacity in Údarás na Gaeltachta client companies in the Donegal Gaeltacht. This region is particularly popular with students of the Ulster dialect; each year thousands of students visit the area from Northern Ireland. Donegal is unique in the Gaeltacht regions, as its accent and dialect is unmistakably northern in character. The language has many similarities with Scottish Gaelic, which are not evident in other Irish dialects.

Gaoth Dobhair in County Donegal is the largest Gaeltacht parish in Ireland, which is home to regional studios of RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta. It has produced well-known traditional musicians, including the bands Altan and Clannad, as well as the artist Enya.

Galway Gaeltacht

The Galway County (Irish: Gaeltacht Chontae na Gaillimhe) and Galway City (Irish: Gaeltacht Chathair na Gaillimhe) Gaeltachtaí[22] have a combined population of 48,907[23] and represent 47% of total Gaeltacht population. The Galway Gaeltacht encompasses a geographical area of 1,225 km2 (473 sq mi). This represents 26% of total Gaeltacht land area. Most speakers are located in the Connemara region. The largest settlement areas are An Spidéal and An Cheathrú Rua. An Cheathrú Rua is 48 km (30 mi) west of Galway City, while An Spidéal is 19 km (12 mi) west of Galway City. There are 30,978 Irish speakers in the Gaeltacht, 11,000 Irish speakers in the Gaeltacht Cois Fharraige and Conamara Theas area including the Aran Islands stretching from Na Forbacha to Carna and another 5,000–7,000 in North Connemara (including the border area with County Mayo) and approximately 4,000 Irish speakers living in areas where the language is spoken by less than 30% of the population. There is also a third-level constituent college of NUIG called Acadamh na hOllscolaíochta Gaeilge in An Cheathrú Rua and Carna. The national Irish-language radio station Raidió na Gaeltachta is located in Casla, Foinse newspaper in An Cheathrú Rua, and national TV station TG4 in Baile na hAbhann. Galway city is home to the Irish language theatre Taibhdhearc na Gaillimhe.

Kerry Gaeltacht

The Kerry Gaeltacht (Irish: Gaeltacht [Chontae] Chiarraí)[24] consists of two areas – the western half of Gaeltacht Corca Dhuibhne (Dingle Peninsula) and central and western parts of Uíbh Ráthach (Iveragh Peninsula). The largest settlement in Corca Dhuibhne is An Daingean and the largest in Uíbh Ráthach is Baile an Sceilg. The Kerry Gaeltacht has a population of 8,729 (6,185 Irish speakers)[25] and represents 9% of total Gaeltacht population. The Kerry Gaeltacht encompasses a geographical area of 642 km2 (248 sq mi). This represents 9% of the total Gaeltacht area.[26]

Mayo Gaeltacht

The Mayo Gaeltacht (Irish: Gaeltacht [Chontae] Mhaigh Eo)[27] as of 2011 has a total population of 10,886[28] and represents 11.5% of the total Gaeltacht population. The Mayo Gaeltacht encompasses a geographical area of 905 km2 (349 sq mi). This represents 19% of the total Gaeltacht land area and comprises three distinct areas – Iorrais, Acaill and Tuar Mhic Éadaigh. Béal an Mhuirthead (Belmullet) is the main town in the Mayo Gaeltacht and is 72 km (45 mi) from Ballina, 80 km (50 mi) from Castlebar and 110 km (68 mi) from Ireland West Airport Knock. There are 6,667[28] Irish speakers, with 4,000 living in areas where the language is spoken by 30–100% of the population and 2,500 living in areas where it is spoken by less than 30%.

Meath Gaeltacht

The Meath Gaeltacht (Irish: Gaeltacht [Chontae] na Mí)[29] is the smallest Gaeltacht area and consists of the two villages of Ráth Cairn and Baile Ghib. Navan, 8 km (5 mi) from Baile Ghib, is the main urban centre within the region, with a population of more than 20,000. The Meath Gaeltacht has a population of 1,771[30] and represents 2% of the total Gaeltacht population. The Meath Gaeltacht encompasses a geographical area of 44 km2 (17 sq mi). This represents 1% of the total Gaeltacht land area.

The Gaeltacht in Meath has a history quite different from that of the country's other Irish speaking regions. The two Gaeltachtaí of Baile Ghib and Ráth Cairn are resettled communities. The Ráth Cairn Gaeltacht was founded in 1935 when 41 families from Connemara in West Galway were resettled on land previously acquired by the Irish Land Commission. Each was given 9 hectares (22 acres) to farm. Baile Ghib (formerly Gibbstown) was settled in the same way in 1937, along with Baile Ailin (formerly Allenstown). In the early years a large percentage of the population returned to Galway or emigrated, but enough Irish speakers remained to ensure that Ráth Cairn and Baile Ghib were awarded Gaeltacht status in 1967. The original aim of spreading the Irish language into the local community met with no success, and the colonists had to become bilingual to farm effectively.[31]

Waterford Gaeltacht

The Waterford Gaeltacht (Irish: Gaeltacht [Chontae] Phort Láirge, Gaeltacht na nDéise)[32][33][34] is ten kilometres (six miles) west of Dungarvan. It embraces the parishes of Rinn Ua gCuanach (Ring) and An Sean Phobal (Old Parish). The Waterford Gaeltacht has a population of 1,784 people (1,271 Irish speakers)[35] and represents 2% of total Gaeltacht population. The Waterford Gaeltacht encompasses a geographical area of 62 km2 (24 sq mi). This represents 1% of total Gaeltacht area.

Administration

The Department of Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs, under the leadership of the Minister for Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs, is responsible for the overall Irish Government policy with respect to the Gaeltacht, and supervises the work of the Údarás na Gaeltachta and other bodies. RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta is the Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ) radio station serving the Gaeltacht and Irish speakers generally. TG4 is the television station which is focused on promoting the Irish language and is based in the County Galway Gaeltacht.

In March 2005, Minister for Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs Éamon Ó Cuív announced that the government of Ireland would begin listing only the Irish language versions of place names in the Gaeltachtaí as the official names, stripping the official Ordnance Survey of their English equivalents, to bring them up to date with roadsigns in the Gaeltacht, which have been in Irish only since 1970. This was done under a Placenames Order made under the Official Languages Act.[36]

Gaeltachtaí in Northern Ireland

Belfast

There is an area in Belfast, known as the Gaeltacht Quarter (An Cheathrú Ghaeltachta), where the Irish language is actively promoted. This is mainly situated along the Falls Road. It has Gaelscoileanna (primary schools), Gaelcholáistí (secondary schools), Naíonraí (crèches), an Irish language restaurant and agencies as well as the Cultúrlann, a cultural centre which also houses Raidió Fáilte (Northern Ireland's only full-time Irish-language radio station). This has grown from the Shaw's Road urban Gaeltacht in the southwest of Belfast. St. Mary's University College Belfast, also situated on the Falls Road is the only teaching college with a dedicated Irish Medium Unit. It is also home to An t-Aisionad (resource center) which translates literature into Irish and publishes it for use in schools and other organisations in Ireland.

County Londonderry

An area in southern County Londonderry centred on Slaghtneill (Sleacht Néill) and Carntogher (Carn Tóchair), which had gone from being 50% Irish-speaking in 1901 to having only a few speakers by the end of the century, has seen a language revival since the setting up of a naíscoil in 1993 and a gaelscoil in 1994. In 2008 two local organisations launched a "strategy for the rebirth of the Gaeltacht", based on Irish-medium primary and secondary education. Speaking at the launch, Éamon Ó Cuív, the Republic's Minister for the Gaeltacht, said that the area was "an example to other areas all over Ireland which are working to reestablish Irish as a community language".[37]

Neo-Gaeltachtaí

Clare Island

An attempt is being made to re-introduce the Irish language as the daily speech of Clare Island (Irish: Oileán Chliara) in County Mayo. The island is situated near the present Mayo Gaeltacht. The island has a small population that reaches 160 in the summer. It has an Irish-speaking school principal who intends to turn the local school into a Gaelscoil. The experiment is said to have considerable local support.[38]

Dublin

Dublin and its suburbs are reported to be the site of the largest number of daily Irish speakers, with 14,229 persons representing 18 per cent of all daily speakers.[39] In a survey of a small sample of adults who had grown up in Dublin and had completed full-time education, 54.2% of respondents reported some fluency in Irish, ranging from being able to make small talk to complete fluency. Only 19% of speakers spoke Irish three or more times per week, with a plurality (42.9%) speaking Irish less than once a fortnight.[40]

It was reported by Nuacht TG4 on 13 January 2009 that a group in the Dublin suburb of Ballymun, in conjunction with the local branch of Glór na Gael had received planning permission to build 38 homes for people who wanted to live in an Irish-speaking community in the city. This project was based on significant local support for the language, since there are 4 Gaelscoileanna and Naíonraí (crèches) in the area, as well as a shop where Irish is spoken. There have been no reports of further progress with this project, which was described as an "urban Gaeltacht".

West Clare

In West Clare a group called Coiste Forbartha Gaeltachta Chontae an Chláir (The Clare Gaeltacht Development Committee) aims to have the area recognised once more as a Gaeltacht. It is claimed that native speakers who received grants under the Scéim Labhairt na Gaeilge, a scheme first established by the State in 1933 with the aim of supporting Gaeltacht families and language promotion in Gaeltacht regions, still live in the county and speak the language daily. It is said that there are up to 170 people who are daily speakers of Irish in County Clare.[41]

Parts of the county were recognised Gaeltacht areas following recommendations made by Coimisiún na Gaeltachta 1926. This was enacted by law under the Gaeltacht (Housing) Acts 1929-2001. Irish speakers living west of Ennis in Kilmihil, Kilrush, Doonbeg, Doolin, Ennistimon, Carrigaholt, Lisdoonvarna and Ballyvaughan consisted of traditional speakers who lived in rural areas unknown to each other. Irish is still spoken daily by some people in Clare [See Profile 9 What We Know An Phríomhoifig Staidrimh / CSO]. Books record the type of traditional Irish spoken in West Clare such as The Dialects of County Clare Part 1 and Part 2, Caint an Chláir, Cuid 1 and Cuid 2, A Comharsain Éistigí agus Amhráin eile as Contae an Chláir and Leabhar Stiofáin Uí Ealaoire. (ISBN 978-0-906426-07-4). "In Ard an Tráthnóna Siar" [2012-2014] is the Kilmihil-based Irish language journal on language planning in West Clare devoted to the restoration of traditional Irish in Gaeltacht Chontae an Chláir [The Clare Gaeltacht]. The committee aims to develop local networks amongst Irish speakers in County Clare and elsewhere until such time as recognition is obtained.[42]

North America

A number of Irish speakers have purchased land in an area near Erinsville, Ontario in Canada and created a Gaeltacht called The Permanent North American Gaeltacht. It was officially opened in 2007 with the Irish Ambassador in attendance.[43]

Irish colleges

Irish colleges are residential Irish language summer courses that give students the opportunity to be totally immersed in the language, usually for periods of three weeks over the summer months. During these courses students attend classes and participate in a variety of different activities games, music, art and sport.

As with the conventional schools, the Department of Education sets out requirements for class sizes and qualifications required by teachers. Some courses are college based and others provide for residence with host families in Gaeltacht areas such as Ros Muc in Galway and Ráth Cairn in County Meath, Coláiste Cill Chartha in County Donegal receiving instruction from a bean an tí, or Irish-speaking landlady.

See also

- Gaeltarra Éireann

- Gàidhealtachd – equivalent region for Scottish Gaelic

- Irish language

- Ulster Irish

- Connacht Irish

- Munster Irish

- Údarás na Gaeltachta

- Y Fro Gymraeg – equivalent region for Welsh

- Shaw's Road

References

- ↑ Webster's Dictionary – definition of Gaeltacht

- ↑ Maguire, Peter A. (Fall 2002). "Language and Landscape in the Connemara Gaeltacht". Journal of Modern Literature 26 (1): 99–107. doi:10.2979/JML.2002.26.1.99.

- ↑ Mac Donnacha, Joe, 'The Death of a Language,' Dublin Review of Books, Issue 58, June 16th, 2014: http://www.drb.ie/essays/the-death-of-a-language

- ↑ "Report of the Gaeltacht Commission" (PDF). 2002. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ pobail.ie

- ↑ "Census 2006 – Volume 9 – Irish Language". CSO. 2007.

- ↑ "Flawed Gaeltacht Bill in need of brave revision". The Irish Times. 3 July 2012.

- ↑ Ó hÉallaithe, Donncha (July 2012). "Teorainneacha na Gaeltachta faoin mBille Nua". Beo.

- ↑ "Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2012 Annual Report" (PDF). An Coimisinéir Teanga. 2012.

- ↑ Walshe, John (11 June 2005). "Number of Gaeltacht schools using Irish 'in steep decline'". The Irish Independent.

- ↑ Council of Europe Charter monitoring report, 2010

- ↑ Census 2006 Principal Demographic Results; Table 33

- ↑ Map of An Ghaeltacht, Údarás na Gaeltachta

- ↑ Donohoe, John (7 April 2010), "Rath Cairn celebrates 75th anniversary with 'páirtí mór'", The Meath Chronicle, retrieved 2 April 2011

- ↑ Kearns, Kevin C. "Resuscitation of the Irish Gaeltacht" (PDF). pp. 88–89.

- ↑ For a description of this in a local area and the steps taken to counter it, see http://www.udaras.ie/en/faoin-udaras/cliant-chomhlachtai/cas-staideir/ceim-aniar-teo-caomhnu-teanga-i-ndun-na-ngall/.

- ↑ udaras.ie

- ↑ "Gaeltacht Area Cork". Central Statistics Office. 2011.

- ↑ udaras.ie

- ↑ debates.oireachtas.ie

- ↑ "Gaeltacht Area Donegal". Central Statistics Office. 2011.

- ↑ udaras.ie

- ↑ "Gaeltacht Area Galway". Central Statistics Office. 2011.

- ↑ udaras.ie

- ↑ "Gaeltacht Area Kerry". Central Statistics Office. 2011.

- ↑ udaras.ie

- ↑ udaras.ie

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Gaeltacht Area Mayo". Central Statistics Office. 2011.

- ↑ udaras.ie

- ↑ "Gaeltacht Area Meath". Central Statistics Office. 2011.

- ↑ Stenson, Nancy (Spring 1986). "Language Report: Rath Cairn, the youngest Gaeltacht". Éire-Ireland: 107–118.

- ↑ udaras.ie

- ↑ debates.oireachtas.ie

- ↑ waterford-news.ie

- ↑ "Gaeltacht Area Waterford". Central Statistics Office. 2011.

- ↑ http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/2003/en/act/pub/0032/index.html Irish Statute Book

- ↑ Irish-Medium Education back bone of the strategy for new Gaeltacht in south Derry, Iontaobhas na Gaelscolaíochta, January 2008. Accessed 5 April 2011

- ↑ Mangan, Stephen (21 August 2010), "Could Clare Island be the next gaeltacht?", The Irish Times, retrieved 27 February 2011

- ↑ "Profile 9 What We Know – Education, skills and the Irish language". CSO. 22 November 2012.

- ↑ Carty, Nicola. "The First Official Language? The status of the Irish language in Dublin" (PDF).

- ↑ "Public Meeting on Clare Gaeltacht Revival". Cogar.ie. 27 January 2012.

- ↑ "Gaeltacht group pressures politicians". The Clare Champion. 16 February 2012.

- ↑ "Gaeltacht Cheanada – Canada's Gaeltacht". Foras na Gaeilge. 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||