GNU Emacs

|

| |

|

GNU Emacs 24.3.1 on GNOME 3 | |

| Original author(s) | Richard Stallman and Guy L. Steele, Jr. |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | GNU Project |

| Initial release | March 20, 1985 |

| Stable release | 24.5 / 10 April 2015 |

| Preview release | 24.4.91 / 8 March 2015 |

| Written in | C, Emacs Lisp |

| Operating system | Cross-platform, GNU |

| Available in | English |

| Type | Text editor |

| License | GNU GPLv3 |

| Website |

www |

GNU Emacs is the most popular and most ported Emacs text editor. It was created by GNU Project founder Richard Stallman. Throughout its history, GNU Emacs has been a central component of the GNU project, and a flagship of the free software movement.[1][2] The tag line for GNU Emacs is "the extensible self-documenting text editor".[3]

History

Richard Stallman began work on GNU Emacs in 1984 to produce a free software alternative to the proprietary Gosling Emacs. GNU Emacs was initially based on Gosling Emacs, but Stallman's replacement of its Mocklisp interpreter with a true Lisp interpreter required that nearly all of its code be rewritten. This became the first program released by the nascent GNU Project. GNU Emacs is written in C and provides Emacs Lisp, also implemented in C, as an extension language. Version 13, the first public release, was made on March 20, 1985. The first widely distributed version of GNU Emacs was version 15.34, released later in 1985. Early versions of GNU Emacs were numbered as "1.x.x," with the initial digit denoting the version of the C core. The "1" was dropped after version 1.12 as it was thought that the major number would never change, and thus the major version skipped from "1" to "13". A new third version number was added to represent changes made by user sites.[4] In the current numbering scheme, a number with two components signifies a release version, with development versions having three components.[5]

GNU Emacs was later ported to Unix. It offered more features than Gosling Emacs, in particular a full-featured Lisp as its extension language, and soon replaced Gosling Emacs as the de facto Unix Emacs editor. Markus Hess exploited a security flaw in GNU Emacs' email subsystem in his 1986 cracking spree in which he gained superuser access to Unix computers.[6]

Although users commonly submitted patches and Elisp code to the net.emacs newsgroup, GNU Emacs development was relatively closed until 1999 and was used as an example of the "Cathedral" development style in The Cathedral and the Bazaar. The project has since adopted a public development mailing list and anonymous CVS access. Development took place in a single CVS trunk until 2008 and today uses the Git [7] DVCS.

Richard Stallman has remained the principal maintainer of GNU Emacs, but he has stepped back from the role at times. Stefan Monnier and Chong Yidong have overseen maintenance since 2008.[8]

Licensing

The terms of the GNU General Public License (GPL) state that the Emacs source code, including both the C and Emacs Lisp components, are freely available for examination, modification, and redistribution.

For GNU Emacs, like many other GNU packages, it remains policy to accept significant code contributions only if the copyright holder executes a suitable disclaimer or assignment of their copyright interest to the Free Software Foundation. Bug fixes and minor code contributions of fewer than 10 lines are exempt. This policy is in place so that the FSF can defend the software in court if its copyleft license is violated.

Older versions of the GNU Emacs documentation appeared under an ad-hoc license that required the inclusion of certain text in any modified copy. In the GNU Emacs user's manual, for example, this included instructions for obtaining GNU Emacs and Richard Stallman's essay The GNU Manifesto. The XEmacs manuals, which were inherited from older GNU Emacs manuals when the fork occurred, have the same license. Newer versions of the documentation use the GNU Free Documentation License with "invariant sections" that require the inclusion of the same documents and that the manuals proclaim themselves as GNU Manuals.

Using GNU Emacs

Commands

In its normal editing mode, GNU Emacs behaves like other text editors and allows the user to insert characters with the corresponding keys and to move the editing point with the arrow keys. Escape key sequences or pressing the control key and/or the meta key, alt key or super keys in conjunction with a regular key produces modified keystrokes that invoke functions from the Emacs Lisp environment. Commands such as save-buffer and save-buffers-kill-emacs combine multiple modified keystrokes.

Some GNU Emacs commands work by invoking an external program, such as ispell for spell-checking or gcc for program compilation, parsing the program's output, and displaying the result in GNU Emacs. Users who prefer IBM Common User Access-style keys can use "cua-mode," a package that originally was a third-party add-on but has been included in GNU Emacs since version 22.

Minibuffer

Emacs uses the "minibuffer," normally the bottommost line, to present status and request information—the functions that would typically be performed by dialog boxes in most GUIs. The minibuffer holds information such as text to target in a search or the name of a file to read or save. When applicable, command line completion is available using the tab and space keys.

File management and display

Emacs keeps text in data structures known as buffers. Buffers may or may not be displayed onscreen, and all buffer features are accessible to an Emacs Lisp program. The user can create new buffers and dismiss unwanted ones, and several buffers can exist at the same time. Some contain text loaded from text files, which the user can edit and save back to permanent storage. These buffers are said to be "visiting" files. Buffers also serve to store temporary text, such as the output of Emacs commands, dired directory listings, documentation strings displayed by the "help" library and notification messages that in other editors would be displayed in a dialog box. Most of Emacs key sequences remain functional in any buffer. For example, the standard Ctrl-s isearch function can be used to search filenames in dired buffers, and the file list can be saved to a text file just as any other buffer.. When so equipped, Emacs displays graphics files in buffers.

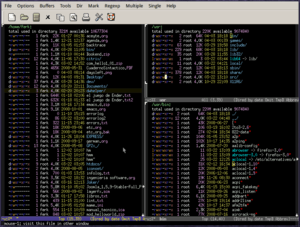

Emacs can split the editing area into separate sections called "windows," a feature that has been available since 1975, predating the graphical user interface in common use. "Windows" in Emacs are similar to what other systems call "frames" or "panes" - a rectangular portion of the program's display that can be updated and interacted with independently. Emacs windows are available both in text-terminal and graphical modes and allow more than one buffer, or several parts of a buffer, to be displayed at once. Common applications are to display a dired buffer along with files in the current directory, to display the source code of a program in one window while another displays a shell buffer with the results of compiling the program, or simply to display multiple files for editing at once—such as a header along with its implementation file for C-based languages. Emacs windows are tiled and cannot appear "above" or "below" their companions. Emacs can launch multiple graphical-environment windows, known in the context of Emacs as "frames". It is possible to create multiple frames on a text terminal; these are displayed stacked filling the entire terminal, and can be switched using the standard Emacs commands.[9]

Major modes

GNU Emacs can edit a variety of different types of text and adapts its behavior by entering add-on modes called "major modes." Defined major modes exist for many different file types including ordinary text files, the source code of many programming languages, HTML documents, and TeX and LaTeX documents. Each major mode involves an Emacs Lisp program that extends the editor to behave more conveniently for the specified type of text. Major modes typically provide some or all of the following common features:

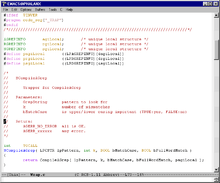

- Syntax highlighting ("font lock"): combinations of fonts and colors, termed "faces,"[10] that differentiate between document elements such as keywords and comments.

- Automatic indentation to maintain consistent formatting within a file.

- The automatic insertion of elements required by the structure of the document, such as spaces, newlines, and parentheses.

- Special editing commands, such as commands to jump to the beginning or the end of a function while editing a programming file or commands to validate documents or insert closing tags while working with markup languages such as XML.

Minor modes

The use of "minor modes" enables further customization. A GNU Emacs editing buffer can use only one major mode at a time, but multiple minor modes can operate simultaneously. These may operate directly on documents, as in the way the major mode for the C programming language defines a separate minor mode for each of its popular indent styles, or they may alter the editing environment. Examples of the latter include a mode that adds the ability to undo changes to the window configuration and one that performs on-the-fly syntax checking. There is also a minor mode that allows multiple major modes to be used in a single file, as required when editing a document in which multiple programming languages are embedded.

Manuals

Apart from the built-in documentation, GNU Emacs has an unusually long and detailed manual. An electronic copy of the GNU Emacs Manual, written by Richard Stallman, is bundled with GNU Emacs and can be viewed with the built-in info browser. Two additional manuals, the Emacs Lisp Reference Manual by Bil Lewis, Richard Stallman, and Dan Laliberte and An Introduction to Programming in Emacs Lisp by Robert Chassell, are included. All three manuals are also published in book form by the Free Software Foundation. The XEmacs manual is similar to the GNU Emacs Manual, from which it forked at the same time that the XEmacs software forked from GNU Emacs.

Internationalization

GNU Emacs has support for many alphabets, scripts, writing systems, and cultural conventions and provides spell-checking for many languages by calling external programs such as ispell. Version 24 added support for bidirectional text and left-to-right and right-to-left writing direction for languages such as Arabic, Persian and Hebrew.

Many encoding systems, including UTF-8, are supported. GNU Emacs uses UTF-8 for its encoding as of GNU 23, while prior versions used their own encoding internally and performed conversion upon load and save. The internal encoding used by XEmacs is similar to that of GNU Emacs but differs in details.

The GNU Emacs user interface originated in English and, with the exception of the beginners' tutorial, has not been translated into any other language.

A subsystem called Emacspeak enables visually impaired and blind users to use the editor through audio feedback.

Extensibility

The behavior of GNU Emacs can be modified and extended almost without limit by incorporating Emacs Lisp programs that define new commands, new buffer modes, new keymaps, and so on. Many extensions providing user-facing functionality define a major mode (either for a new file type or to build a non-text-editing user interface); others define only commands or minor modes, or provide functions that enhance another extension.

Many extensions are bundled with the GNU Emacs installation; others used to be downloaded as loose files (the Usenet newsgroup gnu.emacs.sources was a traditional source) but there has been a development of managed packages and package download sites since version 24, with a built-in package manager (itself an extension) to download and install them.

A few examples include:

- AUCTeX, tools to edit and process TeX and LaTeX documents

- Calc, a powerful RPN numerical calculator

- Calendar-mode, for keeping appointment calendars and diaries

- dired, a file manager

- Dissociated Press, a Racter-like text generator.

- Doctor, a psychoanalysis simulation inspired by ELIZA

- Dunnet, a text adventure

- Ediff and Emerge, for comparing and combining files interactively.

- Emacs/W3, a web browser

- ERC and rcirc and Circe, IRC clients[11]

- Emacs Speaks Statistics (ESS) modes for editing statistical languages like R and SAS

- EWW (Emacs Web Wowser), a built-in web browser

- Gnus, a full-featured newsreader and email client and early evidence for Zawinski's Law

- MULE (MultiLingual extensions to Emacs) allows the editing of text written in multiple languages in a manner somewhat analogous to Unicode

- Org-mode for keeping notes, maintaining various types of lists, planning and measuring projects, and for composing documents in many formats. (Such as PDF, HTML, or OpenDocument formats.)

- Info, an online help-browser

- Planner, a personal information manager

- SES, a spreadsheet

- SLIME[12] extends GNU Emacs into a development environment for Common Lisp. With SLIME (written in Emacs Lisp) the GNU Emacs editor communicates with a Common Lisp system (using the SWANK backend) over a special communication protocol and provides such tools as a read–eval–print loop, a data inspector and a debugger.

- Viper, a vi emulation layer;[13] also, Evil, a Vim emulation layer[14]

- VM (View Mail), another full-featured email client

- Wanderlust, a versatile email and news client

- Mediawiki-mode for editing pages on MediaWiki projects.

Performance

GNU Emacs often ran noticeably slower than rival text editors on the systems in which it was first implemented, because the loading and interpreting of its Lisp-based code incurs a performance overhead. Modern computers are powerful enough to run GNU Emacs without slowdowns, but versions prior to 19.29 (released in 1995) couldn't edit files larger than 8 MB. The file size limit was raised in successive versions, and 32 bit versions after GNU Emacs 23.2 can edit files up to 512 MB in size. Emacs compiled on a 64-bit machine can handle much larger buffers.[15]

Platforms

GNU Emacs has become one of the most-ported non-trivial computer programs and runs on a wide variety of operating systems, including DOS, Microsoft Windows[16][17][18] and OpenVMS. It is available for most Unix-like operating systems, such as Linux, the various BSDs, Solaris, AIX, HP-UX, IRIX and Mac OS X,[19][20] and is often included with their system installation packages. Native ports of GNU Emacs exist for Android[21] and Nokia's Maemo.[22]

GNU Emacs runs both on text terminals and in graphical user interface (GUI) environments. On Unix-like operating systems, GNU Emacs can use the X Window System to produce its GUI either directly using Athena widgets or by using a "widget toolkit" such as Motif, LessTif, or GTK+. GNU Emacs can also use the graphics systems native to Mac OS X and Microsoft Windows to provide menubars, toolbars, scrollbars and context menus conforming more closely to each platform's look and feel.

Forks

XEmacs

Lucid Emacs, based on an early alpha version of GNU Emacs 19, was developed beginning in 1991 by Jamie Zawinski and others at Lucid Inc. One of the best-known early forks in free software development occurred when the codebases of the two Emacs versions diverged and the separate development teams ceased efforts to merge them back into a single program.[23] Lucid Emacs has since been renamed XEmacs and remains the second most popular variety of Emacs, after GNU Emacs. XEmacs development has slowed, with the most recent stable version 21.4.22 released in January 2009, while GNU Emacs has implemented many formerly XEmacs-only features. This has led some users to proclaim XEmacs' death.[24]

Others

Other forks, less known than XEmacs, include:

- Meadow - a Japanese version for Microsoft Windows[25]

- SXEmacs - Steve Youngs' fork of XEmacs[26]

- Aquamacs - a version which focuses on integrating with the Apple Macintosh user interface

Release history

| Version | Release date | Significant changes[27] |

|---|---|---|

| 24.5 | April 10, 2015 | Mainly a bugfix release.[28][29] |

| 24.4 | October 20, 2014 | Support for ACLs (access control lists) and digital signatures of Emacs Lisp packages. Improved fullscreen and multi-monitor support. Support for saving and restoring the state of frames and windows. Improved menu support on text terminals. Built-in web browser (M-x eww). A new rectangular mark mode (C-x SPC). File notification support.[30] |

| 24.3 | March 10, 2013 | Generalized variables are now in core Emacs Lisp, an update for the Common Lisp emulation library, and a new major mode for Python.[31] |

| 24.2 | August 27, 2012 | Bugfix release[32] |

| 24.1 | June 10, 2012 | Emacs Lisp Package Archive, support for native color themes, optional GTK+3, support for bi-directional input, support for lexical scoping in emacs lisp[33] |

| 23.4 | January 29, 2012 | Fixes a security flaw.[34] |

| 23.3 | March 10, 2011 | Improved functionality for using Emacs with version control systems. |

| 23.2 | May 8, 2010 | New tools for using Emacs as an IDE, including navigation across a project and automatic Makefile generation. New major mode for editing JavaScript source. The cursor is hidden while the user types. |

| 23.1 | July 29, 2009 | Support for anti-aliased fonts on X through Xft,[35] better Unicode support, Doc-view mode and new packages for viewing PDF and PostScript files, connection to processes through D-Bus (dbus), connection to the GNU Privacy Guard (EasyPG), nXML mode for editing XML documents, Ruby mode for editing Ruby programs, and more. Use of the Carbon GUI libraries on Mac OS X was replaced by use of the more modern Cocoa GUI libraries. |

| 22.3 | September 5, 2008 | GTK+ toolkit support, enhanced mouse support, a new keyboard macro system, improved Unicode support, and drag-and-drop operation on X. Many new modes and packages including a graphical user interface to GDB, Python mode, the mathematical tool Calc, and the remote file editing system Tramp ("Transparent Remote (file) Access, Multiple Protocol").[36] |

| 22.2 | March 26, 2008 | New support for the Bazaar, Mercurial, Monotone, and Git version control systems. New major modes for editing CSS, Vera, Verilog, and BibTeX style files. Improved scrolling support in Image mode. |

| 22.1 | June 2, 2007 | Support for the GTK+ graphical toolkit, support for drag-and-drop on X, support for the Mac OS X Carbon UI, org-mode version 4.67d included[37] |

| 21.1 | October 20, 2001 | Support for displaying colors and some other attributes on terminals, built-in horizontal scrolling, sound support, wheel mouse support, improved menu-bar layout, support for images, toolbar, and tooltips, Unicode support |

| 20.1 | September 17, 1997 | Multi-lingual support |

| 19.34 | August 22, 1996 | bug fix release with no user-visible changes[38] |

| 19.31 | May 25, 1996[39] | Emacs opens X11 frames by default, scroll bars on Windows 95 and NT, subprocesses on Windows 95, recover-session to recover multiple files after a crash, some doctor.el features removed to comply with the US Communications Decency Act[40] |

| 19.30 | November 24, 1995 | Multiple frame support on MS Windows, menu bar available on text terminals, pc-select package to emulate common Windows and Macintosh keybindings.[41] |

| 19.29 | June 19, 1995[42] | |

| 19.28 | November 1, 1994 | First official v19 release. Support for multiple frames using the X Windowing System; VC, a new interface for version control systems, font-lock mode, hexl mode for hexadecimal editing. |

| 19.7 | May 22, 1993 | |

| 18.59 | October 31, 1992 | |

| 18.53 | February 23, 1989 | |

| 18.52 | August 17, 1988 | spook.el a library for adding some "distract the NSA" keywords to every message you send.[43] |

| 18.24 | October 2, 1986 | Server mode,[44]M-x disassemble, Emacs can open TCP connections, emacs -nw to open Emacs in console mode on xterms. |

| 17.36 | December 20, 1985 | Backup file version numbers |

| 16.56 | July 15, 1985 | First Emacs 16 release. Emacs-lisp-mode distinct from lisp-mode,[45] remove all code from Gosling Emacs due to copyright issues[46] |

| 15.10 | April 11, 1985 | |

| 13.0? | March 20, 1985 |

References

- ↑ "The Linux Programmer's Toolbox".

- ↑ "Learning GNU Emacs".

- ↑ "Debian - details of package Emacs in wheezy".

- ↑ "NEWS.1-17".

There is a new version numbering scheme. What used to be the first version number, which was 1, has been discarded since it does not seem that I need three levels of version number. However, a new third version number has been added to represent changes by user sites. This number will always be zero in Emacs when I distribute it; it will be incremented each time Emacs is built at another site.

- ↑ "GNU Emacs FAQ".

A version number with two components (e.g., ‘22.1’) indicates a released version; three components indicate a development version (e.g., ‘23.0.50’ is what will eventually become ‘23.1’).

- ↑ Stoll, Clifford (1988). "Stalking the wily hacker". Communications of the ACM 31 (5): 484–497. doi:10.1145/42411.42412

- ↑ "Re: GNU EMACS". GNU. Retrieved 2014-11-16.]

- ↑ "Re: Looking for a new Emacs maintainer or team". gnu.org Mailing List. Retrieved 2008-02-23.; see also "Stallman on handing over GNU Emacs, its future and the importance of nomenclature"

- ↑ "Frames - GNU Emacs Manual".

However, it is still possible to create multiple “frames” on text terminals; such frames are displayed one at a time, filling the entire terminal screen

- ↑ Cameron, Debra; Rosenblatt, Bill; Raymond, Eric S. (1996). Learning GNU Emacs. In a Nutshell Series (2 ed.). O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 533. ISBN 978-1-56592-152-8. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

A face is a font and colour combination.

- ↑ Stallman, Richard (2007-06-03). "Emacs 22.1 released". info-gnu-emacs (Mailing list). Retrieved 2011-07-31.

- ↑ SLIME: The Superior Lisp Interaction Mode for Emacs

- ↑ Kifer, Michael. "Emacs packages: Viper and Ediff". Michael Kifer's website. Retrieved 2012-11-15.

- ↑ "Home". Evil wiki. Gitorious. Retrieved 2012-11-15.

- ↑ "6.1 Does Emacs have problems with files larger than 8 megabytes?".

- ↑ B, Ramprasad (2005-06-24). "GNU Emacs FAQ For Windows 95/98/ME/NT/XP and 2000". Retrieved 2006-09-27.

- ↑ Borgman, Lennart (2006). "EmacsW32 Home Page". Retrieved 2006-09-27.

- ↑ "GNU Emacs on Windows". Franz Inc. 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-27.

- ↑ "Carbon Emacs Package". Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- ↑ "Aquamacs is an easy-to-use, Mac-style Emacs for Mac OS X". Retrieved 2006-09-27.

- ↑ "Emacs on Android". EmacsWiki.

- ↑ "CategoryPorts". EmacsWiki.

- ↑ Stephen J., Turnbull. "XEmacs vs. GNU Emacs". Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- ↑ "XEmacs is Dead. Long Live XEmacs!".

- ↑ FrontPage - Meadow Wiki

- ↑ "SXEmacs Website". Sxemacs.org. 2009-10-11. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- ↑ Emacs Timeline. Jwz.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-17.

- ↑ "GNU Emacs NEWS -- history of user-visible changes.". 2015-04-10. Retrieved 2015-04-11.

- ↑ Petton, Nicolas (2015-04-10). "Emacs 24.5 released". Retrieved 2015-04-11.

- ↑ Morris, Glenn (2014-10-20). "Emacs 24.4 released". Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ↑ Morris, Glenn (2013-03-10). "Emacs 24.3 released". Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ↑ Yidong, Chong (2012-08-27). "Emacs release candidate 24.2". Retrieved 2012-11-11.

- ↑ Yidong, Chong (2012-06-01). "Emacs release candidate 24.1". Retrieved 2012-06-01.

- ↑ Yidong, Chong (2012-01-09). "Security flaw in EDE; new release plans". Retrieved 2012-02-23.

- ↑ "emacs-fu: emacs 23 has been released!". Emacs-fu.blogspot.com. 2009-07-28. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- ↑ Zawodny, Jeremy (2003-12-15). "Emacs Remote Editing with Tramp". Linux Magazine. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

Tramp [...] stands for "Transparent Remote (file) Access, Multiple Protocol."

- ↑ Free Software Foundation Inc (2007). "Emacs News version 22.1". Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- ↑ "NEWS.19".

- ↑ "Emacs Timeline".

- ↑ "NEWS.19".

- ↑ "NEWS.19".

- ↑ "GNUs Flashes".

- ↑ "NEWS.18".

- ↑ "NEWS.18".

Programs such as mailers that invoke "the editor" as an inferior to edit some text can now be told to use an existing Emacs process instead of creating a new editor.

- ↑ "NEWS.1-17".

- ↑ "Xemacs Internals".

Further reading

- Stallman, Richard M. (2002). GNU Emacs Manual (15th ed.). GNU Press. ISBN 1-882114-85-X.

- Stallman, Richard M. (2002). "My Lisp Experiences and the Development of GNU Emacs". Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- Chassel, Robert J. (2004). An Introduction to Programming in Emacs Lisp. GNU Press. ISBN 1-882114-56-6.

- Glickstein, Bob (April 1997). Writing GNU Emacs Extensions. O'Reilly & Associates. ISBN 1-56592-261-1.

- Cameron, Debra; Elliott, James; Loy, Marc; Raymond, Eric; Rosenblatt, Bill (December 2004). Learning GNU Emacs, 3rd Edition. O'Reilly & Associates. ISBN 0-596-00648-9.

External links

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||