Fur trade in Montana

The fur trade in Montana was a major period in the area's economic history from about 1800 to the 1850s. It also represents the initial meeting of cultures between indigenous peoples and those of European ancestry. British and Canadian traders approached the area from the north and northeast focusing on trading with the indigenous people, who often did the trapping of beavers and other animals themselves. American traders moved gradually up the Missouri River seeking to beat British and Canadian traders to the profitable Upper Missouri River region.

Indigenous peoples reacted to fur traders in a variety of ways, usually seeking to further their own interests in these economic dealings.[1] Many times, various tribal groups worked well with traders, but sometimes, especially when indigenous interests were threatened, conflicts developed. The best example of conflict on the Upper Missouri was between American fur traders and trappers and the Blackfeet, particularly the Blood. Misunderstanding of indigenous peoples' interests by American traders inevitably led to violence and conflict.[2]

Ultimately, the fur trade brought increased interactions between indigenous peoples and people of American and European ancestry. A capitalistic economic system was introduced to indigenous peoples impacting their cultures, along with deadly diseases that took a heavy toll in lives. The beaver population, and later the bison, were significantly diminished in the area that would become Montana.

Fur trade and indigenous people in Montana

At the start of the 19th century, the North American fur trade was expanding toward present-day Montana from two directions. Representatives of British and Canadian fur trade companies, primarily the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company, pushed west and south from their stronghold on the Saskatchewan River, while American trappers and traders followed the trail of the Lewis and Clark Expedition up the Missouri River from their base in St. Louis.[3] These traders competed not only in trapping fur-bearing animals themselves, particularly the American beaver, but also to arrange trade relations with the many indigenous groups in the region hoping to corner the market on these rich resources. The region's indigenous groups, particularly the Piegan (often called "Blackfeet" in the USA), the Crow, and the Salish and Kootenai, for their part, struggled to maintain control of their own lands and resources that supported their people and way of life. Each group interacted in the fur trade in different ways and to differing extent, yet all were changed by the important trading relations that developed from about 1805 through the 1860s.[4][5][1]

British and Canadian traders

.jpg)

Even while Lewis and Clark struggled to make their way up and over the Rocky Mountains in the summer of 1805, a French Canadian trapper working for the North West Company, François Antoine Larocque explored part of the Yellowstone River drainage in what would become southeastern Montana looking to arrange trading relations with Native Americans in the area, especially the Crow.[6] Though his expedition succeeded, Larocque's long-term plans ultimately failed due to the difficulties of competing with the Hudson's Bay Company and aggressive American fur traders. The North West Company's efforts to establish themselves west of the Continental Divide proved far more successful. Largely avoiding lands known to be within the Louisiana Purchase, the Nor'Westers, led by the Welsh-born geographer, David Thompson, worked their way to the headwaters of the Saskatchewan River and then turned southwestward into the headwaters of the Columbia River. Thompson's men came into present-day northwestern Montana in 1808 and founded a post on the Kootenai River (near present-day Libby, Montana) to trade with the Native Americans of the same name. In November 1809, Thompson himself established the most important post in the area, Saleesh House, on the Clark Fork River near present-day Thompson Falls, Montana, named for the explorer.[7] After many travels and amazingly accurate map-making in the area of the Clark Fork, Kootenai and Flathead rivers, Thompson left the region for good in 1812.[8][9] Through Thompson's efforts and the continuing work of North West Company and later Hudson's Bay Company men like Alexander Ross and Peter Skene Ogden this region came to be dominated by the British and Canadian fur trade for decades to come.[10]

American traders and trappers

American fur traders quickly moved up the Missouri River following the Louisiana Purchase and Lewis and Clark's exploration. The first American fur post established in the region now known as Montana was completed in November 1807, and located at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Big Horn rivers by Manuel Lisa and his party of trappers.[11] Lisa called it Fort Remon for his son, but it was variously known as Lisa's Fort, or Fort Manuel. From this post Lisa hoped to build a small empire for his fledgling Missouri Fur Company. His dream would not last, as he and his men would be the first of many American fur traders to be attacked by groups of Piegan, Blood, and Gros Ventre.[12] The post at the mouth of the Big Horn would be abandoned by 1811 and Lisa's efforts ended in failure.[13]

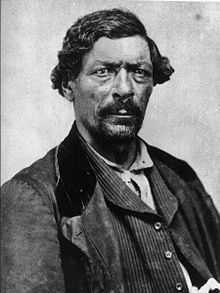

Following another failed attempt in 1823, to establish operations on the upper Missouri River, an innovative enterprise lead by William H. Ashley and Andrew Henry, that would later be called the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, initiated the free trapping and rendezvous system. Ashley and Henry's strategy came to rely predominantly on individual trappers and depended far less on formal trade with indigenous groups. They also abandoned the use of trading posts, relying instead on an annual gathering, or rendezvous, with free trappers and Native people. Their trappers included Jim Bridger, James Beckwourth, Jedediah Strong Smith, William Sublette, and David Edward Jackson. Avoiding the more dangerous territories to the north, they focused their trapping in the Snake River country of present-day Idaho and ranged along rivers and streams in present-day Wyoming and Utah, though the occasional large party of well-armed Rocky Mountain Fur Company trappers made their way through southern portions of what would become Montana. In 1824, Smith, Sublette, and Jackson took over the company and continued to focus trapping in areas to the south of Montana.[14][15]

.jpg)

John Jacob Astor's American Fur Company (AMC) set up operations in St. Louis in 1822. By 1828 they arrived in the upper Missouri River region. Scotsman Kenneth McKenzie, intent on breaking into the Upper Missouri—the elusive prize of the Western fur trade—established what would become Fort Union near the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers. The Piegan were surprisingly ready to trade with the AFC. In 1830, McKenzie negotiated an agreement with a Piegan band and then he sent James Kipp to the mouth of the Marias River in 1831, to organize a trading post on Piegan lands. The AFC soon established a similar post to trade with the Crow on the Yellowstone. In 1832, the paddle steamer Yellowstone, was the first to reach Fort Union. Steamboats, being able to haul larger loads, provided a decided transportation advantage to the AFC thereafter.[16] Astor's company dominated the trade in the entire Missouri River region, wresting the lucrative Upper Missouri trade from the Hudson's Bay Company traders to the north who had traded with the Piegan for decades.[5] Unable to match the resources of the AFC, their main American rival, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company sold out in 1834.[17][16]

Consequences of the fur trade in Montana

The coming of the fur trade to Montana brought several substantial results. First of all, the land and its resources became better known, maps were filled in and became more accurate.[18] As Montana historian K. Ross Toole put it, "Before the emigrant's wagon ever rolled a mile, before the miner found his first color, before the government authorized a single road or trail, this inhospitable land had been traversed and mapped."[19] A negative consequence of the trade was its impact on fur-bearing animals, initially the beaver and later the American bison or buffalo, whose populations were pushed to the brink. The worst consequence physically was the ravages of European diseases such as smallpox increasingly spread to Native Americans by traders and trappers.[20] Finally, for those who survived, the fur trade intensified the introduction of Western European ideals of economics and religion, for the beaver trade was an extension of global capitalism and indirectly lead to the spread of Roman Catholic Christianity to some of the tribes.[21] These changes greatly impacted the Native Americans of the region, challenging their already distressed way of life and changing their world forever.[20][22]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Binnema 2006, pp. 327–349.

- ↑ Binnema & Dobak 2009, pp. 411–440.

- ↑ Toole 1959, pp. 41–43.

- ↑ Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, pp. 41–59.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Smyth 1984, pp. 2–15.

- ↑ Holmes 2008, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ White, pp. 251–263.

- ↑ Holmes 2008, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, pp. 42–45.

- ↑ Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, pp. 45–47.

- ↑ Toole 1959, p. 43.

- ↑ Binnema 2006, pp. 327–330.

- ↑ Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, pp. 47–49.

- ↑ Toole 1959, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, pp. 54–56.

- ↑ Toole 1959, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, p. 57.

- ↑ Toole 1959, p. 55.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, p. 59.

- ↑ Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Holmes 2008, pp. 92–96.

References

- Binnema, Theodore (Ted) (Autumn 2006). "Allegiances and interests : Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) trade, diplomacy, and warfare, 1806–1831". Western Historical Quarterly 37 (3): 327–349. doi:10.2307/25443373. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Binnema, Ted; Dobak, William A. (Fall 2009). ""Like the greedy wolf" : the Blackfeet, the St. Louis fur trade, and war fever, 1807–1831". Journal of the Early Republic 29 (3): 411–440. doi:10.1353/jer.0.0089. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- Holmes, Krys (2008). Montana : stories of the land. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. Retrieved 14 November 2014. Chap. 4 and Chap. 5

- Malone, Michael P.; Roeder, Richard B.; Lang, William L. (1991). Montana : a history of two centuries (Revised ed.). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Smyth, David (Spring 1984). "The struggle for the Piegan trade : the Saskatchewan vs. the Missouri". Montana The Magazine of Western History 34 (2): 2–15. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Toole, K. Ross (1959). Montana : an uncommon land. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- White, M. Catherine (July 1942). "Saleesh House : the first trading post among the Flathead". Pacific Northwest Quarterly 33 (3): 251–263. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Young, Edgerton R. (1899). Winter Adventures of Three Boys in the Great Lone North. London: Charles H. Kelly.

Further reading

- Chittenden, Hiram M. (1986). The American fur trade of the far West. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. Two volumes, reprint of work first published in 1902, considered a seminal work on the American fur trade.

- Graves, F. (1994). Montana's Fur Trade Era. Helena, Montana: Montana Magazine and American & World Geographic Pub. ISBN 1560370548.

- Hamilton, James McClellan; Burlingame, Merrill G. (1957). "Part II-The Period of Fur Trade". From Wilderness to Statehood: A History of Montana, 1805–1900. Portland, OR: Binfords & Mort. pp. 56–92.

- Exploration and development (Video cassette). Montana State University. 1984.

Describes the relationship between native peoples of Montana and the buffalo. The Lewis and Clark expedition and explorations by David Thompson led to the development of the fur trade in the state. Increased contact with whites introduced the Indians to disease, alcohol, and a new economy based on the fur trade.

- Sister, Frances Therese Shea (1944). Typical aspects of the fur trade in the Montana Rockies (Thesis (MA)). Marquette University.

- Wishart, David J. (1992). The Fur Trade of the American West 1807–1840, A Geographical Synthesis. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-4705-2.

- David Thompson Sesquicentennial Symposium, 1809–1959, Sandpoint, Idaho, August 29, 1959. Sandpoint, ID: Bonner County Museum. 1960.

- "Trails of the Past:Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800–1960, The Fur Trade". U.S. Forest Service. January 18, 2010. Retrieved 2014-11-15.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||