Funeral

A funeral is a ceremony for celebrating, respecting, sanctifying, or remembering the life of a person who has died. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember the dead, from interment itself, to various monuments, prayers, and rituals undertaken in their honor. Customs vary widely among cultures, as well as, religious affiliations within cultures.

The word funeral comes from the Latin funus, which had a variety of meanings, including the corpse and the funerary rites themselves. Funerary art is art produced in connection with burials, including many kinds of tombs, and objects specially made for burial with a corpse.

Overview

Funeral rites are as old as human culture itself, pre-dating modern Homo sapiens and dated to at least 300,000 years ago.[1] For example, in the Shanidar Cave in Iraq, in Pontnewydd Cave in Wales and at other sites across Europe and the Near East,[1] archaeologists have discovered Neanderthal skeletons with a characteristic layer of flower pollen. This deliberate burial and reverence given to the dead has been interpreted as suggesting that Neanderthals had religious beliefs,[1] although the evidence is not unequivocal – while the dead were apparently buried deliberately, burrowing rodents could have introduced the flowers.

Religious funerals

Funerals in the Bahá'í Faith

Funerals in the Bahá'í Faith are characterized by not embalming, a prohibition against cremation, using a chrysolite or hardwood casket, wrapping the body in silk or cotton, burial not farther than an hour (including flights) from the place of death, and placing a ring on the deceased's finger stating, "I came forth from God, and return unto Him, detached from all save Him, holding fast to His Name, the Merciful, the Compassionate." The Bahá'í funeral service also contains the only prayer that's permitted to be read as a group - congregational prayer, although most of the prayer is read by one person in the gathering. The Bahá'í decedent often controls some aspects of the Bahá'í funeral service, since leaving a will and testament is a requirement for Bahá'ís. Since there is no Bahá'í clergy, services are usually conducted under the guise, or with the assistance of, a Local Spiritual Assembly.[2]

Buddhist funerals

Christian funerals

Hindu funerals

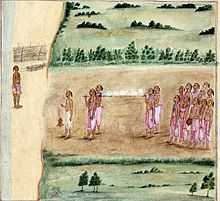

Antyesti or Hindu funeral rites, sometimes referred as Antim Sanskar, is an important Sanskara, sacrament of Hindu society. Extensive texts of such rites are available, particularly in the Garuda Purana. Hindus believe in reincarnation and view death as the soul moving from one body to the next on its path to reach Nirvana, heaven. Death is a sad occasion, but Hindu priests emphasise the route ahead for the departed soul and a funeral is as much a celebration as a remembrance service.

Hindus cremate their dead, believing that the burning of a dead body signifies the release of the spirit and that the flames represent Brahma, the creator.

Family members will pray around the body as soon as possible after death. People will try to avoid touching the corpse as it is considered polluting. The corpse usually is bathed and dressed in white, traditional Indian clothes. If a wife dies before her husband she is dressed in red bridal clothes. If a woman is a widow she will be dressed in white or pale colours.

The funeral procession may pass places of significance to the deceased, such as a building or street. Prayers are said here and at the entrance to the crematorium.

The body is decorated with sandalwood, flowers, and garlands. Scriptures are read from the Vedas or Bhagavad Gita. The chief mourner, usually the eldest son or male of the family, will light some kindling and circle the body, praying for the well being of the departing soul.

After the cremation, the family may have a meal and offer prayers in their home. Mourners wash and change completely before re-entering the house after the funeral. A priest will visit and purify the house with spices and incense. This is the beginning of the thirteen-day mourning period when friends will visit and offer their condolences.

'Shradh' is practiced three year after the death of the person. This may be either an annual event or a large one-time event. This is the Hindu practice of giving food to the poor in memory of the deceased. A priest will say prayers for the deceased and during this time, usually lasting one month, the family will not buy any new clothes or attend any parties. Sons are responsible for carrying out Shradh.

1.As Death Approaches: Traditionally, a Hindu dies at home. Nowadays the dying are increasingly kept in hospitals, even when recovery clearly is not possible. Knowing the merits of dying at home among loved ones, Hindus bring the ill home. When death is imminent, kindred are notified. The person is placed in his room or in the entryway of the house, with the head facing east. A lamp is lit near the person's head and concentration on a personal mantra is urged. Kindred keep vigil until the great departure, singing hymns, praying, and reading scripture. If the patient cannot go home, this happens at the hospital, regardless of institutional objections.

2.The Moment of Death: If the dying person is unconscious at departure, a family member chants the mantra softly in the right ear. If none is known, "Aum Namo Narayana" or "Aum Nama Sivaya" is intoned. (This also is used in the case of sudden-death victims, such as on a battlefield or in a car accident.) Holy ash or sandal paste is applied to the forehead, Vedic verses are chanted, and a few drops of milk, Ganga, or other holy water are trickled into the mouth. After death, the body is laid in the home's entryway, with the head facing south, on a cot or the ground—reflecting a return to the lap of Mother Earth. The lamp is kept lit near the head and incense burned. A cloth is tied under the chin and over the top of the head. The thumbs are tied together, as are the big toes. In a hospital, the family has the death certificate signed immediately and transports the body home. Under no circumstances should the body be embalmed or organs removed for use by others. Religious pictures are turned to the wall, and in some traditions mirrors are covered. Relatives are beckoned to bid farewell and sing sacred songs at the side of the body.

3.The Homa Fire Ritual: If available, a special funeral priest is called. In a shelter built by the family, a fire ritual (homa) is performed to bless nine brass kumbhas (water pots) and one clay pot. Lacking the shelter, an appropriate fire is made in the home. The "chief mourner" leads the rites. He is the eldest son in the case of the father's death and the youngest son in the case of the mother's. In some traditions, the eldest son serves for both, or the wife, son-in-law, or nearest male relative.

4.Preparing the Body: The chief mourner now performs arati, passing an oil lamp over the remains, then offering flowers. The same-gender relatives of the deceased carry the body to the back porch, remove the clothes and drape it with a white cloth. (If there is no porch, the body may be given a sponge bath and prepared where it is.) Each applies sesame oil to the head, and the body is bathed with water from the nine kumbhas, dressed, placed in a coffin (or on a palanquin) and carried to the homa shelter. The young children, holding small lighted sticks, encircle the body, singing hymns. The women then walk around the body and offer puffed rice into the mouth to nourish the deceased for the journey ahead. A widow will place her tali (wedding pendant) around her husband's neck, signifying her enduring tie to him. The coffin is then closed. If unable to bring the body home, the family arranges to clean and dress it at the mortuary, rather than leave these duties to strangers. The ritual homa fire may be made at home or kindled at the crematorium.

5.Cremation: Only men go to the cremation site, led by the chief mourner. Two pots are carried: the clay kumbha and another containing burning embers from the homa. The body is carried three times counterclockwise around the pyre, then placed upon it. All circumambulating, and some arati, in the rites is counterclockwise. If a coffin is used, the cover is now removed. The men offer puffed rice as the women did earlier, cover the body with wood and offer incense and ghee. With the clay pot on his left shoulder, the chief mourner circles the pyre while holding a fire brand behind his back. At each turn around the pyre, a relative knocks a hole in the pot with a knife, letting water out, signifying life's leaving its vessel. At the end of three turns, the chief mourner drops the pot. Then, without turning to face the body, he lights the pyre and leaves the cremation grounds. The others follow. At a gas-fueled crematorium, sacred wood and ghee are placed inside the coffin with the body. Where permitted, the body is carried around the chamber, and a small fire is lit in the coffin before it is consigned to the flames. The cremation switch then is engaged by the chief mourner.

6.Return Home, Ritual Impurity: Returning home, all bathe and share in cleaning the house. A lamp and water pot are set where the body lay in state. The water is changed daily, and pictures remain turned to the wall. The shrine room is closed, with white cloth draping all icons. During these days of ritual impurity, family and close relatives do not visit the homes of others, although neighbors and relatives bring daily meals to relieve the burdens during mourning. Neither do they attend festivals and temples, visit swamis, nor take part in marriage arrangements. Some observe this period up to one year. For the death of friends, teachers, or students, observances are optional. While mourning never is suppressed or denied, scriptures admonish against excessive lamentation and encourage joyous release. The departed soul is acutely conscious of emotional forces received and prolonged grieving can hold the soul in earthly consciousness, inhibiting full transition to the heavenly worlds. In Hindu Bali, it is shameful to cry for the dead.

7.Bone-Gathering Ceremony: About 12 hours after cremation, family men return to collect the remains. Water is sprinkled on the ash; the remains are collected on a large tray. At crematoriums the family may arrange to gather the remains personally: ashes and small pieces of white bone called "flowers." In crematoriums these are ground to dust, and arrangements must be made to preserve them. Ashes are carried or sent to India for deposition in the Ganges or to place them in an auspicious river or the ocean, along with garlands and flowers.

8.First Memorial: On the 12th Day, relatives gather for a meal of the deceased's favorite foods. A portion is offered before a photograph of the deceased and later ceremonially left at an abandoned place, along with some lit camphor. Customs for this period are varied. Some offer pinda (rice balls) daily for nine days. Others combine all these offerings with the following sapindikarana rituals for a few days or one day of ceremonies.

9.31st-Day Memorial: On the thirty-first day, a memorial service is held. In some traditions it is a repetition of the funeral rites. At home, all thoroughly clean the house. A priest purifies the home, and performs the sapindikarana, making one large pinda (representing the deceased) and three small pinda, representing the father, grandfather, and great-grandfather. The large ball is cut in three pieces and joined with the small pindas to unite the soul ritually with the ancestors in the next world. The pindas are fed to the crows, to a cow, or thrown in a river for the fish. Some perform this rite on the eleventh day after cremation. Others perform it twice: on the thirty-first day or (eleventh, fifteenth, etc.) and after one year. Once the first sapindikarana is completed, the ritual impurity ends. Monthly repetition also is common for one year.

10.Shradh: At the 3 yearly anniversary of the death (according to the moon calendar), a priest conducts the shradh rites in the home, offering pinda to the ancestors. This ceremony is performed yearly after completion of 3 years as long as the sons of the deceased are alive. It is now common in India to observe Shradh for ancestors just prior to the yearly Navaratri festival. This time also is appropriate for cases where the day of death is unknown.

Hindu funeral rites may be simple or exceedingly complex. These ten steps, devotedly completed according to the customs, means, and ability of the family, will properly conclude one earthly sojourn of any Hindu soul.

Islamic funerals

Funerals in Islam (called Janazah in Arabic) follow fairly specific rites, though they are subject to regional interpretation and variation in custom. In all cases, however, sharia (Islamic religious law) calls for burial of the body, preceded by a simple ritual involving bathing and shrouding the body, followed by salat (prayer). Cremation of the body is forbidden.

Burial rituals should normally take place as soon as possible and include:

- Bathing the dead body,[3] except in extraordinary circumstances as in battle of Uhud.[4]

- Enshrouding dead body in a white cotton or linen cloth.[5]

- Funeral prayer(صلاة الجنازة).

- Burial of the dead body in a grave.

- Positioning the deceased so that when his face or body is turned to right side it is faced towards Mecca (Makkah Al-Mukarramah).

Jewish funerals

In Judaism, funerals follow fairly specific rites, though they are subject to variation in custom. Funerals in Judaism share many features with those of Islam. Jewish religious laws such as halakha call for burial of the body, preceded by a basic ritual involving bathing and shrouding the body, accompanied by prayers and readings from the Torah. Cremation of the body is forbidden in Orthodox Judaism, but allowed in Reform Judaism.[6]

Burial rites should normally take place as soon as possible and include:

- Bathing the dead body.

- Enshrouding the dead body. Men are shrouded with a kittel and then (outside the Land of Israel) with a tallit (shawl), while women are shrouded in a plain white cloth.

- Keeping watch over the dead body.

- Burial of the dead body in a grave.[6]

- In many communities, the deceased is positioned so that the feet face the Temple Mount in Jerusalem (in anticipation that the deceased will be facing the reconstructed Third Temple when the messiah arrives and resurrects the dead).[7]

Sikh funerals

In Sikhism death is not considered a natural process, an event that has absolute certainty and only happens as a direct result of God's Will or Hukam. To a Sikh, birth and death are closely associated, because they are both part of the cycle of human life of "coming and going" ( ਆਵਣੁ ਜਾਣਾ, Aana Jaana) which is seen as transient stage towards Liberation ( ਮੋਖੁ ਦੁਆਰੁ, Mokh Du-aar), complete unity with God. Sikhs thus believe in reincarnation.

However, by contrast, the soul itself is not subject to the cycle of birth and death. Death is only the progression of the soul on its journey from God, through the created universe and back to God again. In life, a Sikh always tries to constantly remember death so that he or she may be sufficiently prayerful, detached and righteous to break the cycle of birth and death and return to God.

The public display of grief at the funeral or Antam Sanskar as it is called in the Sikh culture, such as wailing or crying out loud is discouraged and should be kept to a minimum. Cremation is the preferred method of disposal, although if this is not possible any other methods such as burial or submergence at sea are acceptable. Worship of the dead with gravestones, etc. is discouraged, because the body is considered to be only the shell and the person's soul is their real essence.

On the day of the cremation, the body is washed/bath and dressed and then taken to the Gurdwara or home where hymns (Shabads) from Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, the Sikh Scriptures are recited by the congregation, which induce feeling of consolation and courage. Kirtan may also be performed by Ragis while the relatives of the deceased recite "Waheguru" sitting near the coffin. This service normally takes from 30 to 60 minutes. At the conclusion of the service, an Ardas is said before the coffin is taken to the cremation site.

At the point of cremation, a few more Shabads may be sung and final speeches are made about the deceased person. The eldest son or a close relative generally starts the cremation process – light the fire or press the button for the burning to begin. This service usually lasts about 30 to 60 minutes.

The ashes are later collected and disposed by immersing them in the Punjab (five famous rivers in India). Sikhs do not erect monuments over the remains of the dead.

The Sidaran Paath The ceremony in which the Sidharan Paath is begun after the cremation ceremony, may be held when convenient, wherever the Guru Granth Sahib is present:

Hymns are sung from Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. The first five and final verses of "Anand Sahib," the "Song of Bliss," are recited or sung. The first five verses of Sikhism's morning prayer, "Japji Sahib," are read aloud to begin the Sidharan paath. A hukam, or random verse, is read from Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. Ardas, a prayer, is offered. Prashad, a sacred sweet, is distributed. Langar, a meal, is served to guests. While the Sidharan paath is being read, the family may also sing hymns daily. Reading may take as long as needed to complete the paath.

This ceremony is followed by Sahaj Paath Bhog, Kirtan Sohila, night time prayer is recited 1 week and finally Ardas called the "Antim Ardas" ("Final Prayer") is offered the last week.

Western funerals

Classical antiquity

Ancient Greece

_-_Walters_48225.jpg)

The Greek word for funeral – kēdeía (κηδεία) – derives from the verb kēdomai (κήδομαι), that means attend to, take care of someone. Derivative words are also kēdemón (κηδεμών, "guardian") and kēdemonía (κηδεμονία, "guardianship"). From the Cycladic civilization in 3000BC until the Hypo-Mycenaean era in 1200–1100 BC the main practice of burial is interment. The cremation of the dead that appears around the 11th century BC constitutes a new practice of burial and is probably an influence from the East. Until the Christian era, when interment becomes again the only burial practice, both cremation and interment had been practiced depending on the area.[8]

The ancient Greek funeral since the Homeric era included the próthesis (πρόθεσις), the ekphorá (ἐκφορά), the burial and the perídeipnon (περίδειπνον). In most cases, this process is followed faithfully in Greece until today.[9]

Próthesis is the deposition of the body of the deceased on the funereal bed and the threnody of his relatives. Today the body is placed in the casket, that is always open in Greek funerals. This part takes place in the house where the deceased had lived. An important part of the Greek tradition is the epicedium, the mournful songs that are sung by the family of the deceased along with professional mourners (who are extinct in the modern era). The deceased was watched over by his beloved the entire night before the burial, an obligatory ritual in popular thought, which is maintained still.

Ekphorá is the process of transport of the mortal remains of the deceased from his residence to the church, nowadays, and afterward to the place of burial. The procession in the ancient times, according to the law, should have passed silently through the streets of the city. Usually certain favourite objects of the deceased were placed in the coffin in order to "go along with him." In certain regions, coins to pay Charon, who ferries the dead to the underworld, are also placed inside the casket. A last kiss is given to the beloved dead by the family before the coffin is closed.

The Roman orator Cicero describes the habit of planting flowers around the tomb as an effort to guarantee the repose of the deceased and the purification of the ground, a custom that is maintained until today. After the ceremony, the mourners return to the house of the deceased for the perídeipnon, the dinner after the burial. According to archaeological findings–traces of ash, bones of animals, shards of crockery, dishes and basins–the dinner during the classical era was also organized at the burial spot. Taking into consideration the written sources, however, the dinner could also be served in the houses.[10]

Two days after the burial, a ceremony called “the thirds” would take place, while eight days after the burial, the relatives and the friends of the deceased assembled at the burial spot, where “the ninths” would take place, a custom that is maintained until today. In addition to this, in the modern era, memorial services take place 40 days, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 1 year after the death and from then on every year on the anniversary of the death. The relatives of the deceased, for an unspecified length of time that depends on them, are in mourning, during which women wear black clothes and men a black armband.

Ancient Rome

In ancient Rome, the eldest surviving male of the household, the pater familias, was summoned to the death-bed, where he attempted to catch and inhale the last breath of the decedent.

Funerals of the socially prominent usually were undertaken by professional undertakers called libitinarii. No direct description has been passed down of Roman funeral rites. These rites usually included a public procession to the tomb or pyre where the body was to be cremated. The most noteworthy thing about this procession was that the survivors bore masks bearing the images of the family's deceased ancestors. The right to carry the masks in public eventually was restricted to families prominent enough to have held curule magistracies. Mimes, dancers, and musicians hired by the undertakers, as well as professional female mourners, took part in these processions. Less well-to-do Romans could join benevolent funerary societies (collegia funeraticia) that undertook these rites on their behalf.

Nine days after the disposal of the body, by burial or cremation, a feast was given (cena novendialis) and a libation poured over the grave or the ashes. Since most Romans were cremated, the ashes typically were collected in an urn and placed in a niche in a collective tomb called a columbarium (literally, "dovecote"). During this nine-day period, the house was considered to be tainted, funesta, and was hung with Taxus baccata or Mediterranean Cypress branches to warn passersby. At the end of the period, the house was swept out to symbolically purge it of the taint of death.

Several Roman holidays commemorated a family's dead ancestors, including the Parentalia, held February 13 through 21, to honor the family's ancestors; and the Feast of the Lemures, held on May 9, 11, and 13, in which ghosts (larvae) were feared to be active, and the pater familias sought to appease them with offerings of beans.

The Romans prohibited cremation or inhumation within the sacred boundary of the city (pomerium), both from a sacred and civil consideration, so that the priests might not be contaminated by touching a dead body, and so that houses would not be endangered by funeral fires.

Restrictions on the length, ostentation, expense of, and behaviour during funerals and mourning gradually were enacted by a variety of law-givers. Often the pomp and length of rites could be politically or socially motivated to advertise or aggrandise a particular kin group in Roman society. This was seen as deleterious to society and conditions for grieving were set. For instance, under some laws, women were prohibited from loud wailing or lacerating their faces and limits were introduced for expenditure on tombs and burial clothes.

The Romans commonly built tombs for themselves during their lifetime. Hence these words frequently occur in ancient inscriptions, V.F. Vivus Facit, V.S.P. Vivus Sibi Posuit. The tombs of the rich usually were constructed of marble, the ground enclosed with walls, and planted around with trees. But common sepulchres usually were built below ground, and called hypogea. There were niches cut out of the walls, in which the urns were placed; these, from their resemblance to the niche of a pigeon-house, were called columbaria.

Traditional funerals

Within the United States and Canada, in most cultural groups and regions, the funeral rituals can be divided into three parts: visitation, funeral, and the burial service.

Visitation

At the visitation (also called a "viewing", "wake" or "calling hours"), in Christian or secular Western custom, the body of the deceased person (or decedent) is placed on display in the casket (also called a coffin, however almost all body containers are caskets). The viewing often takes place on one or two evenings before the funeral. In the past, it was common practice to place the casket in the decedent’s home or that of a relative for viewing. This practice continues in many areas of Ireland and Scotland. The body is traditionally dressed in the decedent's best clothes. In recent times there has been more variation in what the decedent is dressed in – some people choose to be dressed in clothing more reflective of how they dressed in life. The body will often be adorned with common jewelry, such as watches, necklaces, brooches, etc. The jewelry may be taken off and given to the family of the deceased or remain in the casket after burial. Jewelry will most likely be removed before cremation. The body may or may not be embalmed, depending upon such factors as the amount of time since the death has occurred, religious practices, or requirements of the place of burial.

The most commonly prescribed aspects of this gathering are that the attendees sign a book kept by the deceased's survivors to record who attended. In addition, a family may choose to display photographs taken of the deceased person during his/her life (often, formal portraits with other family members and candid pictures to show "happy times"), prized possessions and other items representing his/her hobbies and/or accomplishments. A more recent trend is to create a DVD with pictures and video of the deceased, accompanied by music, and play this DVD continuously during the visitation.

The viewing is either "open casket", in which the embalmed body of the deceased has been clothed and treated with cosmetics for display; or "closed casket", in which the coffin is closed. The coffin may be closed if the body was too badly damaged because of an accident or fire or other trauma, deformed from illness or if someone in the group is emotionally unable to cope with viewing the corpse. In cases such as these, a picture of the deceased, usually a formal photo, is placed atop the casket.

However, this step is foreign to Judaism; Jewish funerals are held soon after death (preferably within a day or two, unless more time is needed for relatives to come), and the corpse is never displayed. As well, Torah law forbids embalming.[11] Traditionally flowers (and music) are not sent to a grieving Jewish family as it is a reminder of the life that is now lost.(See also Jewish bereavement.)

The decedent's closest friends and relatives who are unable to attend frequently send flowers to the viewing, with the exception of a Jewish funeral,[12] where flowers would not be appropriate (and donations are given to a charity instead).

Obituaries sometimes contain a request that attendees omit flowers (e.g. "In lieu of flowers"). The use of these phrases has been on the rise for the past century. In the US in 1927, only 6% of the obituaries included the directive, with only 2.2% of those mentioned charitable contributions as an alternative. By the middle of the century, they had grown to 14.5%, with over 54% of those noting a charitable contribution as the preferred method of expressing sympathy.[13] Today, well over 87% of them have such a note – but those statistics vary demographically.

The viewing typically takes place at a funeral home, which is equipped with gathering rooms where the viewing can be conducted, although the viewing may also take place at a church. The viewing may end with a prayer service; in a Roman Catholic funeral, this may include a rosary. In parts of Ireland and Scotland it is traditional to display the body of the deceased in the family home. This is called a wake and usually includes food, drink and sometimes music and singing.

A visitation is often held the evening before the day of the funeral. However, when the deceased person is elderly the visitation may be held immediately preceding the funeral. This allows elderly friends of the deceased a chance to view the body and attend the funeral in one trip, since it may be difficult for them to arrange travel; this step may also be taken if the deceased has few survivors or the survivors want a funeral with only a small number of guests.

Funeral

A memorial service, often called a funeral, is often officiated by clergy from the decedent's, or bereaved's, church or religion. A funeral may take place at either a funeral home, church, or crematorium or cemetery chapel. A funeral is held according to the family's choosing, which may be a few days after the time of death, allowing family members to attend the service. This type of memorial service is most common for Christians, and Roman Catholics call it a mass when Eucharist (communion) is offered, the casket is closed and a priest says prayers and blessings. A Roman Catholic funeral must take place in a parish church (usually that of the deceased, or that of the family grave, or a parish to which the deceased had special links). Sometimes family members or friends of the dead willl say something. If the funeral service takes place in the funeral home (mostly it takes place in the funeral home's chapel) it can be directed by a clergy (mostly for Protestant churches) or hosted by a very close family member most common a parent. In some traditions if this service takes place in a funeral home it is the same if it would take place in a church. These services if taking place in a funeral home consists of a lot of prayers, blessings and eulogies from the family.

The open-casket service (which is common in North America) allows mourners to have one last opportunity to view the deceased and say good-bye. There is an order of precedence when approaching the casket at this stage that usually starts with the immediate family (siblings, parents, spouse, children); followed by other mourners, after which the immediate family may file past again, so they are the last to view their loved one before the coffin is closed. This opportunity can take place immediately before the service begins, or at the very end of the service.[14] However, a Roman Catholic funeral must be closed-casket, and the relatives of the deceased are supposed to view him during the few days between the death and the service.

Open casket funerals and visitations are very rare in some countries, such as the United Kingdom and most European countries, where it is usual for only close relatives to actually see the deceased person and not uncommon for nobody to do so. The funeral service itself is almost invariably closed casket. Funeral homes are generally not used for funeral services.

The deceased is usually transported from the funeral home to a church in a hearse, a specialized vehicle designed to carry casketed remains. The deceased is often transported in a procession (also called a funeral cortege), with the hearse, funeral service vehicles, and private automobiles traveling in a procession to the church or other location where the services will be held. In a number of jurisdictions, special laws cover funeral processions – such as requiring other vehicles to give right-of-way to a funeral procession, excepting service vehicles and ambulances. Funeral service vehicles may be equipped with light bars and special flashers to increase their visibility on the roads. They may also all have their headlights on, to identify which vehicles are part of the cortege, although the practice also has roots in ancient Roman customs.[15] After the funeral service, if the deceased is to be buried the funeral procession will proceed to a cemetery if not already there. If the deceased is to be cremated, the funeral procession may then proceed to the crematorium.

Funeral services commonly include prayers, readings from a sacred text, hymns (sung either by the attendees or a hired vocalist) and words of comfort by the clergy. Frequently, a relative or close friend will be asked to give a eulogy, which details happy memories and accomplishments; often commenting on the deceased's flaws, especially at length, is considered impolite. Sometimes the delivering of the eulogy is done by the clergy. Clergy are often asked to deliver eulogies for people they have never met. Church bells may also be tolled both before and after the service.

In some religious denominations, for example, Roman Catholic, Anglican and the Churches of Christ, eulogies from loved ones are somewhat discouraged during this service, in order to preserve respect for traditions. In such cases, the eulogy is only done by a member of the clergy. This tradition is giving way to eulogies read by family members or friends in a desire to ensure that it is done, "just right." Also, for these same religions, the coffin is traditionally closed at the end of the wake and is not re-opened for the funeral service.

During the funeral and at the burial service, the casket may be covered with a large arrangement of flowers, called a casket spray. If the deceased served in a branch of the Armed forces, the casket may be covered with a national flag; however, in the US, nothing should cover the national flag according to Title 4, United States Code, Chapter 1, Paragraph 8i.

Funeral customs vary from country to country. In the United States, any type of noise other than quiet whispering or mourning is considered disrespectful.

A traditional Fire Department funeral consists of two raised aerial ladders. The firefighter(s) travel under the aerials on their ride, on the fire apparatus, to the cemetery. Once there, the grave service includes the playing of bagpipes. The pipes have come to be a distinguishing feature of a fallen hero's funeral. Also a "Last Alarm Bell" is rung. A portable fire department bell is tolled at the conclusion of the ceremony.

Burial service

At a burial service, conducted at the side of the grave, tomb, mausoleum or cremation, the body of the decedent is buried or cremated at the conclusion.

Sometimes, the burial service will immediately follow the funeral, in which case a funeral procession travels from the site of the memorial service to the burial site. In some other cases, the burial service is the funeral, in which case the procession might travel from the cemetery office to the gravesite. Other times, the burial service takes place at a later time, when the final resting place is ready, if the death occurred in the middle of winter.

If the decedent served in a branch of the Armed forces, military rites are often accorded at the burial service.

In many religious traditions, pallbearers, usually males who are close, but not immediate relatives (such as cousins, nephews or grandchildren) or friends of the decedent, will carry the casket from the chapel (of a funeral home or church) to the hearse, and from the hearse to the site of the burial service. The pallbearers often sit in a special reserved section during the memorial service.

According to most religions, coffins are kept closed during the burial ceremony. In Eastern Orthodox funerals, the coffins are reopened just before burial to allow loved ones to look at the deceased one last time and give their final farewells. Greek funerals are an exception as the coffin is open during the whole procedure unless the state of the body does not allow it.

The morticians will typically ensure that all jewelry, including wristwatch, that were displayed at the wake are in the casket before it is buried or entombed. Custom requires that everything goes into the ground; however this is not true for Jewish services. Jewish tradition is that nothing of value is buried with the deceased.

There is an exception, in the case of cremation. Such items tend to melt or suffer damage, so they are usually removed before the body goes into the furnace. Pacemakers are removed prior to cremation – if they were left in they could possibly explode and damage the crematorium.

Local burial traditions

Even within a single country many local areas have their own unique burial traditions. For example, funerals on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland are often followed by a traditional Lewis funeral procession[16] which involves mourners taking turns at carrying the coffin en route to the graveyard.

Similarly burials on the Isle of Jura and parts of the Isle of Islay are often followed by whisky, cheese and biscuits at the graveside, a tradition which stems from the time when the long journey to the graveyard was taken on foot.

Etiquette in different countries

Generally speaking, the number of people who are considered obliged to attend each of these three rituals by etiquette decreases at each step:

- Distant relatives and acquaintances may be called upon to attend the visitation.

- The decedent's closer relatives and local friends attend the funeral or memorial service, and subsequent burial (if it is held immediately after the memorial service).

- If the burial is on the day of the funeral, only the decedent's closest relatives and friends attend the burial service (although if the burial service immediately follows the funeral, all attendees of the memorial service are asked to attend).

Traditionally etiquette dictated that the bereaved and other attendees at a funeral wear formal clothing, such as a suit and tie for men or a dress for women. The most traditional color is solid black (with a matching solid black tie for men) preferably without any underlying pinstripes or patterns in the weave. But failing that charcoal gray or dark navy blue may be worn.

Wearing short skirts, low-cut tops, T-shirts with advertising slogans or suggestive images, or, at Western funerals, a large amount of white (other than a button-down shirt or blouse, a military uniform, or in the Swedish tradition, white ties worn by male members of the immediate family) is often seen as disrespectful.

Women who are grieving the deaths of their husbands or close partners sometimes wear a veil to conceal their faces, although this practice is not presently common. Increasingly, the deceased have requested before their death that the attendees of their funeral should wear something of their favorite color or wear something specific, such as a football shirt.

A guest book may be placed in a prominent place during the viewing. It is intended to let the next of kin know who came to the funeral, so that thank-you letters can be mailed. It is not intended to be read by the funeral directors as a source of referrals, so it is not the best place for comments on the appropriateness of the funeral arrangements. Disagreements on such matters can have lasting effects and can even affect inheritances.

Private services

On occasion, the family of the deceased may wish to have only a very small service, with just the deceased's closest family members and friends attending. This type of ceremony means it is closed to the public. One may only go to the funeral if one is invited. In this case, a private funeral service is conducted. Reasons vary but often include the following:

- The deceased was an infant (possibly, they may have been stillborn) or very aged, and therefore has few surviving family members or friends.

- The deceased may be a crime victim or a convicted criminal who was serving a prison sentence or executed. In this case, the service is made private either to avoid unwanted media coverage (especially with a crime victim); or to avoid unwanted intrusion (especially if the deceased was convicted of murder or sexual assault).

- The family does not feel able to endure a traditional service (due to emotional shock) or simply wants a quiet, simple funeral with only the most important people of the deceased's life in attendance.

- The family and/or the deceased, as more frequently preplanned, prefer simplicity and lower cost to that of traditional arrangements. The choice of cremation as an option to casketed burial is increasing and often includes disposition of the cremated remains at a time privately convenient to the deceased's family members.

- The deceased is of a distinct celebrity status, and holding public ceremony would result in too many guests who are not acquainted with the deceased to participate. On the other hand, if a state funeral is offered and accepted by the deceased's immediate family, a public funeral would ensue.

Memorial services

The memorial service is a service given for the deceased when the body is not present. The service takes place after inhumation or burial at sea, after donation of the body to an academic or research institution, or after the cremated remains have been scattered. It is also significant when the person is missing and presumed dead, or known to be deceased though the body is not recoverable. These services often take place at a funeral home; however, they can be held in a home, school, workplace, or other location of some significance. A memorial service may include speeches (eulogies), prayers, poems, or songs to commemorate the deceased. Pictures of the deceased and flowers are usually placed at the altar where the body would normally be placed.

After the sudden deaths of important public officials, public memorial services have been held by communities, including those without any specific connection to the deceased. For examples, community memorial services were held after the assassination of James A. Garfield and the assassination of William McKinley.

Funerals in Scotland

An old funeral rite from the Scottish Highlands is to bury the deceased with a wooden plate resting on his chest. In the plate were placed a small amount of earth and salt, to represent the future of the deceased. The earth hinted that the body would decay and become one with the earth, while the salt represented the soul, which does not decay. This rite was known as "earth laid upon a corpse". This practice was also carried out in Ireland, as well as in parts of England, particularly in Leicestershire, although in England the salt was intended to prevent air from distending the corpse.[17]

Other types of funerals

New Orleans jazz funeral

A unique funeral tradition in the United States occurs in New Orleans, Louisiana. The tradition arose from a combination of African spiritual practices, French musical traditions, and African-American cultural influences.

A typical jazz funeral begins with a march by the family, friends, and a jazz band, starting from the home, funeral home, or church, and proceeding to the cemetery. Throughout the march, the band plays very somber dirges. Once the final ceremony has been completed, the march proceeds to a gathering place, and the solemn music is replaced by loud, upbeat, raucous music and dancing, where onlookers join in to celebrate the life of the deceased. Celebration of those who still have survived death, "the butcher", ensues. This is the origin of the New Orleans dance known as the "second line" where celebrants do a dance-march, frequently while raising the hats and umbrellas brought along as protection from intense New Orleans weather and waving handkerchiefs above the head that are no longer being used to wipe away tears. Aspects of this tradition have been practiced in other locations by long-time devotees of jazz.

Green funeral

Those with concerns about the effects on the environment of traditional burial or cremation may choose to be buried in a fashion more suited to their beliefs. They may choose to be buried in an all natural bio-degradable green burial shroud, sometimes a simple coffin made of cardboard or other easily biodegradable material. Further, they may choose their final resting place to be in a park or woodland, known as an eco-cemetery, and may have a tree planted over their grave as a contribution to the environment and a remembrance.

Humanist funeral

Non-religious funerals are legal within the UK. The British Humanist Association organises a network of humanist funeral celebrants or officiants across England and Wales,[18][19] and a similar network is organised by the Humanist Society of Scotland. Humanist officiants are trained and experienced in devising and conducting suitable ceremonies.[20] Humanist funerals recognise no "after-life", but celebrate the life of the person who has died.[18] Humanist funerals have reportedly been held in recent years for Claire Rayner,[21] Keith Floyd,[22][23] Linda Smith,[24] and Ronnie Barker,[25] among others.

Civil funeral

Civil funerals are an alternative to religious or humanist ceremonies in the UK. Unlike a humanist funeral, a civil funeral can contain some religious content, such as hymns or reading if the family wish.[26]

Police/fire services funerals

Funerals for fallen members of fire or police services are common in United States and Canada. These funerals involve honour guards from police forces and/or fire services from across the country and sometimes from overseas. The presence of outside members is regarded as a sign of respect and support from the brotherhood of fellow officers.

In the case of a fallen firefighter, the casket is often placed on top of a fire engine and draped with a flag. For both fire and police, a parade of officers often precedes or follows the hearse carrying the fallen comrade.

Masonic funeral

A Masonic funeral is held at the request of a departed Brother or his family. The service may be held in a chapel, home, church, synagogue or Lodge room with committal at graveside, or the complete service can be performed at any of the aforementioned places without a separate, committal.

No one is ever obligated to have a Masonic Funeral. It is not a requirement of the Fraternity that a member have his funeral service conducted, either in whole or in part, by the Masonic Order. Any member who was in good standing at the time of his death may have a Masonic Funeral if he requested it or if his family so requests. Any participation in tire service, other than the attendance of individual Lodge members as a part of the general congregation, is always by request to the Fraternity.

There is no single Masonic Funeral Service. Some Grand Lodges (it is a world-wide organisation) have a prescribed service. Some of the customs involved may seem unusual to non-Masons. For example, the presiding officer may wear a hat while doing his part in the service, the Lodge members may place sprigs of evergreen on the casket, and a small white leather apron may be placed in or on the casket. The hat may be worn because it is Masonic custom (in some places in the world) for the presiding officer to have his head covered while officiating. To Masons the sprig of evergreen is a symbol of immortality. The white leather apron, called a "lambskin," is the badge of a Mason and it is his to wear, even in death. He wore that apron when he was made a Mason, on the day he received his first degree. Sometimes the wording of the Masonic Services is a bit old and archaic, and may reflect the thinking and values of an earlier day.[27][28]

East Asian funerals

In most East Asian, South Asian and many Southeast Asian cultures, the wearing of white is symbolic of death. In these societies, white or off-white robes are traditionally worn to symbolize that someone has died and can be seen worn among relatives of the deceased during a funeral ceremony. In Chinese culture, red is strictly forbidden as it is a traditionally symbolic color of happiness. Exceptions are sometimes made if the deceased has reached a high age, particularly between their mid-80s to age 100. In which case, the funeral is considered a celebration, where wearing white with some red is acceptable. Contemporary Western influence however has meant that dark-colored or black attire is now often also acceptable for mourners to wear (particularly for those outside the family). In such cases, mourners wearing dark colors at times may also wear a white or off-white armband or white robe.

In Southern China a traditional Chinese gift to the attendees upon entering is a white (and sometimes red) envelope, usually enclosing a small sum of money (in odd numbers, usually one dollar), a sweet, red thread, and a handkerchief, each with symbolic meaning. Chinese custom also dictates that the said sum of money should not be brought home. The sweet should be consumed the day of and anything given during the funeral must not be brought home. The exception is the red thread, which is tied to the front doorknob of the guest's house to ward off bad luck. The repetition of 3 is common where people at the funeral may brush their hair three times or spit three times before leaving the funeral to ward off bad luck. This custom is also found in other East Asian and Southeast Asian cultures however the custom the deceased's immediate family giving gifts and money to others involved in the funeral is not practiced in Northern China.

Most Japanese funerals are conducted with Buddhist rites. Many feature a ritual that bestows a new name on the deceased; funerary names typically use obsolete or archaic kanji and words, to avoid the likelihood of the name being used in ordinary speech or writing. The new names are typically chosen by a Buddhist priest, after consulting the family of the deceased. Most Japanese are cremated.

Contemporary South Korean funerals typically mix western culture with traditional Korean culture, largely depending on socio-economic status, region, and religion. In almost all cases, all related males in the family wear woven arm bands representing seniority and lineage in relation to the deceased, and must grieve next to the deceased for a period of three days before burying the body. During this period of time, it is customary for the males in the family to personally greet all who come to show respect. While burials have been preferred historically, recent trends show a dramatic increase in cremations due to shortages of proper burial sites and difficulties in maintaining a traditional grave. The ashes of the cremated corpse are commonly stored in columbaria.

Funerals in Japan

_shaving_the_head_of_the_dead_in_Japan-J._M._W._Silver.jpg)

Religious thought among the Japanese people is generally a blend of Shintō and Buddhist beliefs. In modern practice, specific rites concerning an individual's passage through life are generally ascribed to one of these two faiths. Funerals and follow-up memorial services fall under the purview of Buddhist ritual, and 90% Japanese funerals are conducted in a Buddhist manner. Aside from the religious aspect, a Japanese funeral usually includes a wake, the cremation of the deceased, and inclusion within the family grave. Follow-up services are then performed by a Buddhist priest on specific anniversaries after death.

According to one estimate made in 2005, 99.82% of all deceased Japanese are cremated.[29] In most of these cases, the cremated remains are placed in an urn and then deposited in a family grave. In recent years however, alternative methods of burial have gained in popularity; such methods include scattering of the ashes, burial in outer space, and conversion of the cremated remains into a diamond that can be set in jewelry.

Funerals in the Philippines

Funeral practices and burial customs in the Philippines encompass a wide range of personal, cultural, and traditional beliefs and practices which Filipinos observe in relation to death, bereavement, and the proper honoring, interment, and remembrance of the dead. These practises have been vastly shaped by the variety of religions and cultures that entered the Philippines throughout its complex history.

Most if not all present-day Filipinos, like their ancestors, believe in some form of an afterlife and give considerable attention to honouring the dead.[30] Except amongst Filipino Muslims (who are obliged to bury a corpse less than 24 hours after death), a wake is generally held from three days to a week.[31] Wakes in rural areas are usually held in the home, while in urban settings the dead is typically displayed in a funeral home. Apart from spreading the news about someone’s death verbally,[31] obituaries are also published in newspapers. Although the majority of the Filipino people are Christians,[32] they have retained some traditional indigenous beliefs concerning death.[33][34]

African funerals

West African funerals

African funerals are usually open to many visitors. The custom of burying the dead in the floor of dwelling-houses has been to some degree prevalent on the Gold Coast of Africa. The ceremony is depends on the traditions of the tribe the deceased belonged to. The funeral may last for as much as a week. Another custom, a kind of memorial, frequently takes place seven years after the person's death. These funerals and especially the memorials may be extremely expensive for the family in question. Cattle, sheep, goats, and poultry, may be offered and then consumed.

The Ashanti and Akan ethnic groups in Ghana will typically wear red and black during funerals. For special family members, there is typically a funeral celebration with singing and dancing to honor the life of the deceased. Afterwards, the Akan hold a sombre funeral procession and burial with intense displays of sorrow. Other funerals in Ghana are held with the deceased put in elaborate "fantasy coffins" colored and shaped after a certain object, such as a fish, crab, boat, and even airplanes.[35] The Kane Kwei Carpentry Workshop in Teshie, named after Seth Kane Kwei who invented this new style of coffin, has become an international reference for this form of art.

Some diseases, such as Ebola can be spread by funerary customs including touching the dead. However, safe burials can be achieved by following simple procedures. For example, letting relatives see the face of the dead before bodybags are closed and taking photographs, if desired, can greatly reduce the risk of infection without impacting too heavily on the customs of burial.[36]

East African funerals

In Kenya funerals are an expensive undertaking. Keeping bodies in morgues to allow for fund raising is a common occurrence more so in urban areas. Some families opt to bury their dead in the countryside homes instead of urban cemeteries, thus spending more money on transporting the dead.

Mutes and professional mourners

From about 1600 to 1914, there were two professions in Europe now almost totally forgotten. The mute is depicted in art quite frequently but in literature is probably best known from Dickens's Oliver Twist. Oliver is working for Sowerberry when this conversation takes place: "There's an expression of melancholy in his face, my dear... which is very interesting. He would make a delightful mute, my love". And in Martin Chuzzlewit, Moult, the undertaker, states, "This promises to be one of the most impressive funerals,...no limitation of expense...I have orders to put on my whole establishment of mutes, and mutes come very dear, Mr Pecksniff." The main purpose of a funeral mute was to stand around at funerals with a sad, pathetic face. A symbolic protector of the deceased, the mute would usually stand near the door of the home or church. In Victorian times, mutes would wear somber clothing including black cloaks, top hats with trailing hatbands, and gloves.[37]

The professional mourner, generally a woman, would shriek and wail (often while clawing her face and tearing at her clothing), to encourage others to weep. These people are mentioned in ancient Greek plays, and were commonly employed throughout Europe until the beginning of the nineteenth century. They continue to exist in Africa and the Middle East. The 2003 award-winning Philippine comedy Crying Ladies revolves around the lives of three women who are part-time professional mourners for the Chinese-Filipino community in Manila's Chinatown. According to the film, the Chinese use professional mourners to help expedite the entry of a deceased loved one's soul into heaven by giving the impression that he or she was a good and loving person, well loved by many.

State funeral

Military and high-ranking political figures such as Lord Nelson, Sir Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan were offered state funerals.

Final disposition of the dead

Some cultures place the dead in tombs of various sorts, either individually, or in specially designated tracts of land that house tombs. Burial in a graveyard is one common form of tomb. In some places, burials are impractical because the groundwater is too high; therefore tombs are placed above ground, as is the case in New Orleans, Louisiana. Elsewhere, a separate building for a tomb is usually reserved for the socially prominent and wealthy; grand, above-ground tombs are called mausoleums. The socially prominent sometimes had the privilege of having their corpses stored in church crypts. In more recent times, however, this has often been forbidden by hygiene laws. Burial was not always permanent. In some areas, burial grounds needed to be reused due to limited space. In these areas, once the dead have decomposed to skeletons, the bones are removed; after their removal they can be placed in an ossuary.

Burial at sea

"Burial at sea" means the deliberate disposal of a corpse into the ocean, wrapped and tied with weights to make sure it sinks. It is a common practice in navies and seafaring nations; in the Church of England, special forms of funeral service were added to the Book of Common Prayer to cover it.

Space burial

Science fiction writers have frequently analogized with "burial in space".

Cremation

Cremation is also an old custom; it was the usual mode of disposing of a corpse in ancient Rome (along with graves covered with heaped mounds, also found in Greece, particularly at the Karameikos graveyard in Monastiraki). Vikings were occasionally cremated in their longships, and afterwards the location of the site was marked with standing stones.

In recent years, despite the objections of some religious groups, cremation has become increasingly popular. Jewish law (Halakha) forbids cremation to Orthodox Jews, believing that the soul of a cremated person will be unable to find its final repose. The Roman Catholic Church forbade it for many years, but since 1963 the church has allowed it, as long as it is not done to express disbelief in bodily resurrection. The church specifies that cremated remains are either buried or entombed; they do not allow cremated remains to be scattered or kept at home. Many Catholic cemeteries now have columbarium niches for cremated remains, or specific sections for those remains. Some denominations of Protestantism allow cremation, the more conservative denominations generally do not. The Eastern Orthodox Church and Islam also forbid cremation.

In Hindu culture

.jpg)

Hindus consider the funeral as the final samskar, or "ritual of life". Cremation is generally mandatory for all Hindus, except for saints and children under the age of 5 years. Cremation is seen as the only way in which all five elements—fire, water, earth, air, and space would be satisfied by returning the body to these elements as after cremation the ashes are poured into the sacred river Ganges or into the sea. After death the body of the deceased is placed on the ground with the head of the deceased pointing towards south which is considered the direction of the dead. The body is anointed with sacred items such as sandalwood paste and holy ashes, tulsi (basil) leaves and water from the Ganges. The eldest son would whisper "Om namah shivay" or "Om namo bhagavate vasudevaya" to the deceased. An oil lamp is lit besides the deceased and chapters from the Bhagavad Gita or Garuda Purana are recited. Traditionally the body has to be cremated within 24 hours after death, as keeping the body longer is considered to lead to impurity and hinder the passage of the dead to afterlife. Hence before cremation as the body lies in state, minimal physical contact with the body is observed.[38]

A Hindu priest conducts the formal rituals, after which the body is taken to the cremation ground, where the eldest son lights the funeral pyre. This act is considered to be the most important duty of a son as it is believed that he leads his parents from this world into moksha. Immediately after the cremation, the family members of the deceased all have to take a purifying bath and observe a 12‑day mourning period. This mourning period ends on the morning of the thirteenth day on which a Shraddh ceremony is conducted in which offerings are given to ancestors and other gods in order to grant liberation, or moksha, to the deceased.

Exposure to scavenger animals

Rarer forms of disposal of the dead include exposure to the elements and to scavenger animals. This includes various forms of excarnation, where the corpse is stripped of the flesh, leaving only the bones, which are then either buried or stored elsewhere, in ossuaries or tombs for example. This was done by some groups of Native Americans in protohistoric times. Ritual exposure of the dead (without preservation of the bones) is practiced by Zoroastrians in Bombay and Karachi, where bodies are placed in "Towers of Silence", where vultures and other carrion eating birds then dispose of the corpses. In the present-day structures, the bones are collected in a central pit where (assisted by lime) they, too, eventually decompose. Exposure to scavenger birds (with preservation of some, but not all bones) is also practiced by some high-altitude Tibetan Buddhists, where practical considerations (the lack of firewood and a shallow active layer) seem to have led to the practice known as jhator or "giving alms to the birds".

Cannibalism

Cannibalism has earlier been practiced post-mortem in parts of Papua New Guinea. The practice has been linked to the spread of a prion disease called kuru.[39]

Mummification

Mummification is the drying of bodies to preserve them. The most famous practitioners were ancient Egyptians—many nobles and highly ranked bureaucrats had their corpses embalmed and stored in luxurious sarcophagi inside their funeral mausoleums. Pharaohs stored their embalmed corpses in pyramids.

Promession

Promession is a new method of disposing of the body. Patented by a Swedish company, a promession is also known as an "ecological funeral". Its main purpose is to return the body to soil quickly while minimizing pollution and resource consumption.[38]

Control by the decedent of the details of the funeral

Some people choose to make their funeral arrangements in advance so that at the time of their death, their wishes are known to their family. However, the extent to which decisions regarding the disposition of a decedent's remains (including funeral arrangements) can be controlled by the decedent while still alive vary from one jurisdiction to another. In the United States, there are states which allow one to make these decisions for oneself if desired, for example by appointing an agent to carry out one's wishes; in other states, the law allows the decedent's next-of-kin to make the final decisions about the funeral without taking the wishes of the decedent into account.[40]

Of course, most family members of a deceased person would regard any wishes the deceased had made known as carrying considerable moral authority. Generally, some people may feel that it is a person's right to have their wishes regarding their own body and the manner in which they are memorialized respected after death, while others may feel that funerals are rather for the benefit of the living than of the dead.

The decedent may, in most U.S. jurisdictions, provide instructions as to his funeral by means of a last will and testament. These instructions can be given some legal effect if bequests are made contingent on the heirs carrying them out, with alternative gifts if they are not followed. This assumes, of course, that the decedent has enough of an estate to make the heirs pause before doing something that will invoke the alternate bequest. To be effective, the will or other instrument stating the decedent's funeral wishes must be easily available, and some notion of what it provides must be known to the decedent's survivors: aspects of the disposition of the remains of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ran contrary to a number of his stated wishes, which were found in a safe that was opened after the funeral.[41]

Anatomical gifts

Another way of avoiding some of the rituals and costs of a traditional funeral is for the decedent to donate some or all of her or his body to a medical school or similar institution for the purpose of instruction in anatomy, or for similar purposes. Students of medicine and osteopathic medicine frequently study anatomy from donated cadavers; they are also useful in forensic research.

Making an anatomical gift is a separate transaction from being an organ donor, in which any useful organs are removed from the unembalmed cadaver for medical organ transplant. Under a Uniform Act in force in most jurisdictions of the United States, being an organ donor is a simple process that can often be accomplished when a driver's license is renewed. There are some medical conditions, such as amputations, or various surgeries, that can make the cadaver unsuitable for these purposes. Conversely, the bodies of people who had certain medical conditions are useful for research into those conditions. All US medical schools rely on the generosity of "anatomical donors" for the teaching of anatomy. Typically the remains are cremated once the students have completed their anatomy classes, and many medical schools now hold a memorial service at that time as well.[42]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "When Burial Begins", British Archaeology, issue 66, August 2002, found at British Archaeology website. Accessed September 4, 2008.

- ↑ Kitáb-i-Aqdas, p. 65

- ↑ Sahih al-Bukhari 1254

- ↑ Sahih al-Bukhari 1346

- ↑ Sahih Muslim 943

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Jewish Funeral Traditions". Everplans. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ↑ "Are Bodies Buried in a Specific Direction?". Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ↑ Lemos 2002: Lemos I., The Protogeometric Aegean. The Archaeology of the Late Eleventh and Tenth Centuries BC, Oxford

- ↑ IMS.forth.gr

- ↑ Ανώνυμος Πιστός και Απολογητής του Χριστού. "Apologitis.com". Apologitis.com. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ "Torah law forbids embalming". Chabad.org. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ Jewish Funeral and Mourning Customs

- ↑ A Centennial History of the AMERICAN FLORIST, a publication of Florists’ Review Enterprises, Inc., Frances Porterfield Dudley, Publisher, 1997.

- ↑ Iserson 1994: 445.

- ↑ Olmert, Michael (1996). Milton's Teeth and Ovid's Umbrella: Curiouser & Curiouser Adventures in History, p.34. Simon & Schuster, New York. ISBN 0-684-80164-7.

- ↑ The Guardian: Linda Norgrove funeral takes place http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/oct/26/linda-norgrove-funeral-afghanistan

- ↑ "Salt", IN: The Table Book of Daily Recreation and Information; Concerning Remarkable Men, Manners, Times, Seasons, Solemnities, Merry-Makings, Antiquities and Novelties, Forming a Complete History of the Year, ed. William Hone, (London: 1827) p 262. Retrieved on 2008-07-02.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Humanist Funerals and Memorials". Humanism.org.uk. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ "Humanist funerals". IfIShouldDie.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- ↑ "Non-religious funerals". BBC. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ "Jennifer Lipman, Agony aunt Claire Rayner dies at age 79', Jewish Chronicle, 12 October 2010". Thejc.com. 2010-10-12. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ Haroon Siddique and agencies (2009-09-30). "Haroon Siddique, Mourners pay tribute to TV chef Keith Floyd at humanist funeral, The Guardian, 30 September 2009". Guardian. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ Count, The (2009-09-30). "Bristol Evening Post, Keith Floyd funeral in Bristol, 30 September 2009". Bristolpost.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ "Linda Smith: God, the biggest joke of all". Independent.co.uk. 2006-03-02. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ "BBC, Family funeral for Ronnie Barker, 13 October 2005". BBC News. 2005-10-13. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ "About Civil Funerals". Institute of Funeral Celebrants. Retrieved 2014-02-19.

Offered in England since April 2002, the Civil Funeral is a ceremony that reflects the beliefs and values of the deceased rather than those of the minister, officiant or Celebrant.

- ↑ Colon, Felix. "Masonic Funerals". THE MASONIC SERVICE ASSOCIATION. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ http://grandlodgeofiowa.org/docs/ObituaryRites/MasonicMemorialHandbook.pdf

- ↑ "Cremation Society of G.B. – International Cremation Statistics 2005". Srgw.demon.co.uk. 2007-02-06. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ Filipinos and Funeral Traditions, Organ-ic Chemist, musical-chemist.blogspot.com, January 24, 2009

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Clark, Sandi. Death and Loss in the Philippines, Grief in a Family Context, HPER F460, Summer, 1998, indiana.edu

- ↑ Guballa, Cathy Babao. Grief in the Filipino Family Context, indiana.edu

- ↑ Pagampao, Karen. A Celebration of Death Among the Filipino, bosp.kcc.hawaii.edu

- ↑ Tacio, Henrylito D. Death Practices Philippine Style, sunstar.com, October 30, 2005

- ↑ "Funeral and Religious Customs". A-to-z-of-manners-and-etiquette.com. 1936-01-10. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ Accessed 2014 http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/bringing-safer-burial-rituals-ebola-countries/

- ↑ Bertram S. Puckle, Funeral Customs: Their Origin and Development (London: T. W. Laurie, ltd., 1926) p. 66.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Promessa.se Accessed March 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Kuru: Prion Diseases: Merck Manual Home Edition". Merckmanuals.com. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ Who Has the Right to Make Decisions About Your Funeral?, www.qeepr.com, February 5, 2014

- ↑ "Funeral Directions - In Your Will". Haddletonlaw.com. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ Roach, Mary. Stiff: The Curious Lives Of Human Cadavers. Penguin. ISBN 0141007451.

Bibliography

- Akyel, Dominic. From Detraditionalization to Price-consciousness: The Economization of Funeral Consumption in Germany. In Uwe Schimank and Ute Volkmann (ed.) The Marketization of Society: Economizing the Non-Economic. Bremen: Research Cluster “Welfare Societies”, 2012, pp. 105–124.

- Iserson, Kenneth V. (1994). Death to Dust: What Happens to Dead Bodies?. Tucson, AZ: Galen Press, Ltd.

- Roach, Mary. Stiff: The Curious Lives Of Human Cadavers. Penguin. ISBN 0141007451.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Funeral. |

- Funeral at DMOZ

- Funeral Planning Guide Resources for planning and conducting a funeral.

- Environmentally Friendly Burials Guide Guide to environmentally friendly burials

- funeral homes in Florida

- Funeral Planning Infographic Quick 10 Things to think about funeral planning

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||