Fundamental theorem of Galois theory

In mathematics, the fundamental theorem of Galois theory is a result that describes the structure of certain types of field extensions.

In its most basic form, the theorem asserts that given a field extension E/F that is finite and Galois, there is a one-to-one correspondence between its intermediate fields and subgroups of its Galois group. (Intermediate fields are fields K satisfying F ⊆ K ⊆ E; they are also called subextensions of E/F.)

Explicit description of the correspondence

For finite extensions, the correspondence can be described explicitly as follows.

- For any subgroup H of Gal(E/F), the corresponding fixed field, denoted EH, is the set of those elements of E which are fixed by every automorphism in H.

- For any intermediate field K of E/F, the corresponding subgroup is Aut(E/K), that is, the set of those automorphisms in Gal(E/F) which fix every element of K.

The fundamental theorem says that this correspondence is a one-to-one correspondence if (and only if) E/F is a Galois extension. For example, the topmost field E corresponds to the trivial subgroup of Gal(E/F), and the base field F corresponds to the whole group Gal(E/F).

The notation Gal(E/F) is only used for Galois extensions. If E/F is Galois, then Gal(E/F) = Aut(E/F). If E/F is not Galois, then the "correspondence" gives only an injective (but not surjective) map from  subgroups of Aut(E/F)

subgroups of Aut(E/F) to

to  subfields of E/F

subfields of E/F , and a surjective (but not injective) map in the reverse direction. In particular, if E/F is not Galois, then F is not the fixed field of any subgroup of Aut(E/F).

, and a surjective (but not injective) map in the reverse direction. In particular, if E/F is not Galois, then F is not the fixed field of any subgroup of Aut(E/F).

Properties of the correspondence

The correspondence has the following useful properties.

- It is inclusion-reversing. The inclusion of subgroups H1 ⊆ H2 holds if and only if the inclusion of fields EH1 ⊇ EH2 holds.

- Degrees of extensions are related to orders of groups, in a manner consistent with the inclusion-reversing property. Specifically, if H is a subgroup of Gal(E/F), then |H| = [E:EH] and |Gal(E/F)/H| = [EH:F].

- The field EH is a normal extension of F (or, equivalently, Galois extension, since any subextension of a separable extension is separable) if and only if H is a normal subgroup of Gal(E/F). In this case, the restriction of the elements of Gal(E/F) to EH induces an isomorphism between Gal(EH/F) and the quotient group Gal(E/F)/H.

Example 1

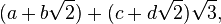

Consider the field K = Q(√2, √3) = Q(√2)(√3). Since K is first determined by adjoining √2, then √3, each element of K can be written as:

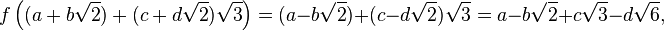

where a, b, c, d are rational numbers. Its Galois group G = Gal(K/Q) can be determined by examining the automorphisms of K which fix a. Each such automorphism must send √2 to either √2 or −√2, and must send √3 to either √3 or −√3 since the permutations in a Galois group can only permute the roots of an irreducible polynomial. Suppose that f exchanges √2 and −√2, so

and g exchanges √3 and −√3, so

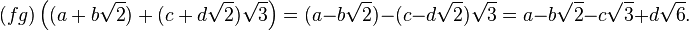

These are clearly automorphisms of K. There is also the identity automorphism e which does not change anything, and the composition of f and g which changes the signs on both radicals:

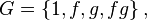

Therefore

and G is isomorphic to the Klein four-group. It has five subgroups, each of which correspond via the theorem to a subfield of K.

- The trivial subgroup (containing only the identity element) corresponds to all of K.

- The entire group G corresponds to the base field Q.

- The two-element subgroup {1, f } corresponds to the subfield Q(√3), since f fixes √3.

- The two-element subgroup {1, g} corresponds to the subfield Q(√2), again since g fixes √2.

- The two-element subgroup {1, fg} corresponds to the subfield Q(√6), since fg fixes √6.

Example 2

The following is the simplest case where the Galois group is not abelian.

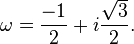

Consider the splitting field K of the polynomial x3−2 over Q; that is, K = Q (θ, ω), where θ is a cube root of 2, and ω is a cube root of 1 (but not 1 itself). For example, if we imagine K to be inside the field of complex numbers, we may take θ to be the real cube root of 2, and ω to be

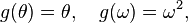

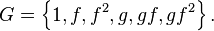

It can be shown that the Galois group G = Gal(K/Q) has six elements, and is isomorphic to the group of permutations of three objects. It is generated by (for example) two automorphisms, say f and g, which are determined by their effect on θ and ω,

and then

The subgroups of G and corresponding subfields are as follows:

- As usual, the entire group G corresponds to the base field Q, and the trivial group {1} corresponds to the whole field K.

- There is a unique subgroup of order 3, namely {1, f, f 2}. The corresponding subfield is Q(ω), which has degree two over Q (the minimal polynomial of ω is x2 + x + 1), corresponding to the fact that the subgroup has index two in G. Also, this subgroup is normal, corresponding to the fact that the subfield is normal over Q.

- There are three subgroups of order 2, namely {1, g}, {1, gf } and {1, gf 2}, corresponding respectively to the three subfields Q(θ), Q(ωθ), Q(ω2θ). These subfields have degree three over Q, again corresponding to the subgroups having index 3 in G. Note that the subgroups are not normal in G, and this corresponds to the fact that the subfields are not Galois over Q. For example, Q(θ) contains only a single root of the polynomial x3−2, so it cannot be normal over Q.

Applications

The theorem classifies the intermediate fields of E/F in terms of group theory. This translation between intermediate fields and subgroups is key to showing that the general quintic equation is not solvable by radicals (see Abel–Ruffini theorem). One first determines the Galois groups of radical extensions (extensions of the form F(α) where α is an n-th root of some element of F), and then uses the fundamental theorem to show that solvable extensions correspond to solvable groups.

Theories such as Kummer theory and class field theory are predicated on the fundamental theorem.

Infinite case

There is also a version of the fundamental theorem that applies to infinite algebraic extensions, which are normal and separable. It involves defining a certain topological structure, the Krull topology, on the Galois group; only subgroups that are also closed sets are relevant in the correspondence.

References

| ||||||