Frost diagram

A Frost diagram or Frost-Ebsworth diagram is a type of graph used by inorganic chemists in electrochemistry to illustrate the relative stability of a number of different oxidation states of a particular substance. Frost diagrams will be different at different pHs, so the pH must be specified.

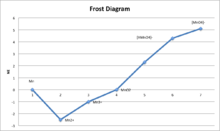

Frost Diagram

Used frequently in electrochemistry, half reactions of oxidation-reduction reactions have reduction potentials that determine the increases or decreases in free energy. The Frost diagram allows for easier comprehension of these reduction potentials than the earlier-designed Latimer Diagram, because the “lack of additivity of potentials” was confusing.[1] Frost introduced this diagram as a qualitative substitution for the Latimer, and graphs oxidation state vs. free energy. The free energy ΔG° is related to reduction potential E in the graph by given formula: ΔG°= -nFE° or nE°= -ΔG°/F where n is the number of transferred electrons and F is Faraday’s Constant (F= 96,485 J/(V mol)) [2]

pH dependence

The pH dependence is given by the factor -0.059m/n per pH unit, where m relates to the number of protons in the equation, and n the number of electrons exchanged. Electrons are always exchanged in electrochemistry, but not necessarily protons. If there is no proton exchange in the reaction equilibrium, the reaction is said to be pH-independent. This means that the values for the electrochemical potential rendered in a redox half-reaction, whereby the element/s in question change/s oxidation state are the same whatever the pH conditions under which the procedure is carried out.

The Frost diagram is also a useful tool for comparing the trends of standard potentials (slope) of acidic and basic solutions. The pure, neutral element transitions to different compounds depending whether the species is in acidic and basic pHs. Though the value and amount of oxidation states remain unchanged, the free energies can vary greatly. The Frost diagram allows the superimposition of acidic and basic graphs for easy and convenient comparison.

Unit and Scale

The standard free energy scale is measured in electron volts.[1] and the nE°= 0 value is usually the pure, neutral element. The Frost diagram normally shows free energy values above and below nE°=0 and is scaled in integers. The y-axis of the graph displays the free energy. Increasing stability (lower free energy) is lower on the graph, so the higher free energy and higher on the graph an element is, the more unstable and reactive it is.[2]

The oxidation state of the element is shown on the x-axis of the Frost diagram. Oxidation states are unitless and are also scaled in positive and negative integers. Most often, the Frost diagram displays oxidation number in increasing order, but in some cases it is displayed in decreasing order. The neutral, pure element with a free energy of zero (nE°=0) also has an oxidation state equal to zero.[2]

The slope of the line therefore represents the standard potential between two oxidation states. In other words, the steepness of the line shows the tendency for those two reactants to react and form the lowest energy product.[1] There is a possibility of having either a positive or negative slope. A positive slope between two species indicates a tendency for an oxidation reaction, while a negative slope between two species indicates a tendency for reduction. For example if [HMnO4]− has an oxidation state of +6 and nE°=4 and MnO2 has an oxidation state of +4 and nE°=0. The slope is calculated by Δy/Δx so in this case 4/2=2 that yields the standard potential of +2. we can find the stability of any terms by this graph

Gradient

The gradient of the line between any two points on a Frost diagram gives the potential for the reaction. A species that lies in a peak, above the gradient of the two points on either side, denotes a species unstable with respect to disproportionation, and a point that falls below the gradient of the line joining its two adjacent points lies in a thermodynamic sink, and is intrinsically stable.

Axes

The axes of the Frost diagram show (horizontally) the oxidation state of the species in question and (vertically) the electron exchange number multiplied by the voltage (nE) OR the Gibbs free energy per unit of the Faraday constant, ΔG/F.

Disproportionation and Conproportionation

In regards to electrochemical reactions, two main types of reactions can be visualized using the Frost diagram. Conproportionation is when two equivalents of an element, differing in oxidation number, combine to form a product with an intermediate oxidation number. Disproportionation is the opposite reaction, in which two equivalents of an element, identical in oxidation number, react to form two products of differing oxidation numbers.[2]

Disproportionation: 2 Mn+ → Mm+ + Mp+

Conproportionation: Mm+ + Mp+ → 2 Mn+

2n=m+p in both examples.[2]

Using a Frost diagram, one can predict whether one oxidation number would undergo dispropotionation or two oxidation numbers would undergo conproportionation. Looking at two slopes among a set of 3 oxidation numbers on the diagram, assuming the two standard potentials (slopes) are not equal, the middle oxidation will either be in a “hill” or “valley” form. A hill is formed when the left slope is steeper than the right, and a valley is formed when the right slope is steeper than the left. An oxidation number that is on “top of the hill” tends to favor disproportionation into the adjacent oxidation states.[1][2] The adjacent oxidation states, however, will favor conproportionation if the middle oxidation state is in the “bottom of a valley”.[2]

Arthur Atwater Frost

Arthur Atwater Frost was a professor of chemistry at Northwestern University when he researched and invented the Frost Diagram in 1950. He originally called these graphs Oxidation Potential-Free Energy Diagrams, but the name was later shortened as his namesake. His discovery was published in 73rd volume of the Journal of the American Chemical Society. He claimed that this new diagram would “show both free energy and oxidation potential data conveniently”.[1]

Criticisms/Discrepancies

Arthur Frost stated in his own original publication that there may be potential criticism for his Frost diagram. He predicts that “the slopes may not be as easily or accurately recognized as they are the direct numerical values of the oxidation potentials [of the Latimer diagram]”.[1] Many inorganic chemists use both the Latimer and Frost diagrams in tandem, using the Latimer for quantitative data, and then converting that data into a Frost diagram for visualization. Frost suggested that the numerical values of standard potentials could be added next to the slopes to provide supplemental information.[1]

In a paper by Jesús M. Martinez de Ilarduya, he warns users of Frost diagrams to be aware of the definition of free energy being used to construct the diagrams. In acid-solution graphs, the standard nE°= -ΔG/F is universally used; therefore all sources’ acid-solution Frost diagrams will be identical. However, various textbooks show discrepancies in the Frost diagram of an element, in regards to the energy. Some textbooks use the same reduction potential (Eo(H+/H2)) as an acid-solution for a basic-solution. In the Phillips and Williams Inorganic Chemistry textbook, however, a new reduction potential is used for the basic solutions given by the following formula: E°(OH)= E°b- E°(H2O/H2OH−)= E°b+ 0.828 .[3] This new type of reduction potential is used in some textbooks and not others, and is not always notated on the graph. Users of the Frost diagram should be aware of which free energy scale their diagram displays.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Frost, Arthur (1951). "Oxidation Potential-Free Energy Diagrams". Journal of the American Chemical Society 73 (6): 2680–2682. doi:10.1021/ja01150a074.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Shriver (2010). Inorganic Chemistry. W.H. Freeman & Co.

- ↑ Phillips, C. S. G. (1965). Inorganic Chemistry. Oxford University. pp. 314–321.

- ↑ Martínez de Illarduya, Jesús M.; Villafane, Fernando (June 1994). "A Warning for Frost Diagram Users". Journal of Chemical Education 71 (6): 480–482. doi:10.1021/ed071p480.