Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás

| Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás | |

|---|---|

May 3, 1877 – April 25, 1933 | |

| Native name | Ferenc Nopcsa |

| Born | Négyfalu, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | Vienna, Austria |

| Citizenship | Austria-Hungary |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Patrons | University of Vienna |

| Known for | Albanology, paleobiology, geology, ethnology |

Baron Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás (also Baron Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás, Baron Nopcsa, Ferenc Nopcsa, Nopcsa Ferenc, Baron Franz Nopcsa, and Franz Baron Nopcsa) (May 3, 1877 – April 25, 1933) was a Hungarian-born aristocrat, adventurer, scholar, and paleontologist. He is widely regarded as one of the founders of paleobiology and Albanian studies.

Life

Nopcsa was born in 1877 in Transylvania, which at that time was part of Austria-Hungary, to the Nopcsa aristocratic family of magyarised Romanian origin. In 1895 Nopcsa's younger sister Ilona discovered dinosaur bones at the family estate at Szentpéterfalva in Săcel (Szacsal), Transylvania. This led to Nopcsa's enrollment at the University of Vienna to study the fossilized bones. He advanced quickly in his studies; he gave his first academic lecture at the age of twenty-two.

In addition to Mesozoic reptiles, Nopcsa's interests included nationhood for Albania, then a mere province of the Turkish-Balkan Ottoman Empire, but aspiring to independence. He was one of the few outsiders who ventured into the mountainous areas in the north of Albania. He soon learned the Albanian dialects and customs.

Eventually, he had good relations with the leaders of the nationalist Albanian resistance against the Turks who occupied the region. Nopcsa gave passionate speeches and smuggled in weapons. In 1912 the Balkan states joined forces to drive out the Turks. This was successful, but the newly liberated states were immediately plunged into internal conflicts. However, out of these conflicts, Albania arose as an independent state. At an international conference aiming to clarify the status of Albania, Nopcsa was at first a contender for the throne of that country.

Later, during the First World War, Nopcsa was a spy for Austria-Hungary. He also led a group of Albanian wartime volunteers. However, with the defeat of Austria-Hungary at the end of the war, Nopcsa's native Transylvania was ceded to Romania. As a consequence, the Baron of Felső-Szilvás lost his estates and other possessions. Compelled to find paid employment, he landed a job as the head of the Hungarian Geological Institute.

But Nopcsa's tenure in the Geological Institute was short-lived. He moved to Vienna with his long-standing Albanian secretary and lover Bayazid Doda (a.k.a. Bajazid Elmas Doda) to study fossils. Yet there he ran into financial difficulties and was distracted in his work. To cover his debts, he sold his fossil collection to the Natural History Museum in London. Soon Nopcsa became depressed. Finally, in 1933, he fatally shot first his friend and then himself.

Nopcsa left behind a considerable quantity of scientific publications and private diaries. The diaries paint a picture of a complex man with great intuition, but without the ability to understand the motives of others. His devotion to the cause of the Albanians was in contrast to his sociopathic insensitivity. In his diaries he nonchalantly wrote about his bid to become king of Albania:

| “ | Once a reigning European monarch, I would have no difficulty coming up with the further funds needed by marrying a wealthy American heiress aspiring to royalty, a step which under other circumstances I would have been loath to take. | ” |

Contributions to paleobiology and geology

Nopcsa's main contribution to paleontology – and hence "paleobiology" – was that he was one of the first researchers who tried to "put flesh onto bones." At a time when paleontologists were mainly interested in assembling bones, he tried to deduce the physiology and living behavior of the dinosaurs he was studying. Nopcsa was the first to suggest that these archosaurs cared for their young and exhibited complex social behavior.

Another of Nopcsa's theories that was ahead of its time was that birds evolved from ground-dwelling dinosaurs, which developed feathers to run faster. This theory found favor in the 1960s and later gained wide acceptance, though later fossil finds of tree-living feathered dinosaurs suggest the development of flight may have been more complex than Nopcsa envisioned. Additionally, Nopcsa's conclusion that at least some Mesozoic era reptiles were warm-blooded is now shared by much of the scientific community.

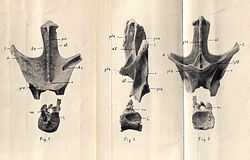

Nopcsa studied Transylvanian dinosaurs intensively, even though they were smaller than their "cousins" elsewhere in the world. For example, he unearthed six-meter-long sauropods, a group of dinosaurs which elsewhere commonly grew to 30 meters or more, which he named Magyarosaurus. Nopcsa deduced that the area where the remains were found was an island, Hațeg Island (now the Haţeg or Hatzeg basin in Romania) during the Mesozoic era. He theorized that "limited resources" found on islands commonly have an effect of "reducing the size of animals" over the generations, producing a localized form of dwarfism. Nopcsa's theory of insular dwarfism—also known as the island rule—is today widely accepted (highlighted by Gareth Dyke in "The Dinosaur Baron of Transylvania" In Scientific American, October 2011, pp. 81–83). Additional pygmy sauropods, named Europasaurus, were recently discovered in northern Germany (analyzed by P. Martin Sander in Nature, 8 June 2006).

Nopcsa also created a theory about the dinosaurs' sexual dimorphism. Among others, he thought that hadrosaurid species with the cranial crests were males and those without them were females. He paired Kritosaurus with Parasaurolophus, Prosaurolophus with Saurolophus and others. His examples were not proved to be true, but his opinion that sexual dimorphism was present among hadrosaurid dinosaurs has gained acceptance, see for example Lambeosaurus.

As a result of the above studies and publications, Nopcsa is sometimes considered to be the "father" of modern paleobiology, even though he originally termed the field as "paleophysiology."

But he was also an important geologist. Indeed, Nopcsa was one of the first scholars to study the geology of the western Balkans, particularly northern Albania.

Contribution to Albanian studies

During his lifetime Nopcsa published more than fifty scientific studies concerning Albania, covering a wide range of linguistics, folklore, ethnology, history and kanun (that is, Albanian customary law). He was the leading expert on Albania in his time.

After Nopcsa's death, several of his important manuscripts were left unpublished. He participated in the work of the Albanian Congress of Trieste, published his notes on the congress that became of particular historical interest.[1] The Albanological part of his estate ended up in the hands of Norbert Jokl, a renowned specialist in Albanian studies. At that time, Nopcsa's material consisted of thousands of pages of notes, sketches, and finished text. Subsequently, this library came into possession of Mid'hat Bey Frashëri. When Frashëri was forced to flee the country, Nopcsa's materials were confiscated by the communist regime of Enver Hoxha. Eventually, Nopcsa's manuscripts, drawings, and completed writings formed the core of the Albanological section of Albania's National Library.

References

- ↑ Elsie, Robert. "Baron Franz Nopcsa and his contribution to Albanian studies". Robert Elsie's personal website. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

Of particular historical interest are Nopcsa's notes on the Albanian Congress of Trieste in 1913 and on the selection of a European noble to become the crowned head of the newly independent principality of Albania.

- István Főzy: Nopcsa báró és a Kárpát-medence dinoszauruszai (Baron Franz Nopcsa and the Dinosaurs of the Carpathian-basin), Alfadat-Press, Tatabánya. ISBN 9638103248.

- Gëzim Alpion (2002): Baron Franz Nopcsa and his Ambition for the Albanian Throne. BESA Journal, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 25–32. ISSN 1366-8536

- Gareth Dyke (2011): The Dinosaur Baron of Transylvania, Scientific American, October, vol. 305, no. 4, pp. 81–83.

- David B. Weishampel and C. M. Jianu (1995). The centennial of Transylvanian dinosaur discoveries: A reexamination of the life of Franz Baron Nopcsa. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15 (3, Suppl.): p. 60A.

- Ing Jaroslav Mareš, (1993). Záhada dinosaurů (The mystery of dinosaurs), Prague, Svoboda-Libertas, ISBN 80-205-0374-9

- Robert Elsie (1999). The Viennese Scholar Who Almost Became King of Albania: Baron Franz Nopcsa and His Contribution to Albanian Studies. East European Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 3, p. 327-345.

- David B. Weishampel and Wolf-Ernst Reif (1984) The Work of Franz Baron Nopcsa (1877-1933): Dinosaurs, Evolution and Theoretical Tectonics. Jb. Geol. B.-A. 127(2):187-203

See also

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ferenc Nopcsa. |

- Baron Franz Nopcsa and the Dinosaurs of the Carpathian-basin – a book discussion in English by István Fõzy, A. Fogarasi, and O. Szives (2001), three Hungarian paleontologists (the first is the author).

- San Francisco Chronicle, "Studies reveal pygmy dinosaur species" 8 June 2006.

- Baron Franz Nopcsa and His Dream for the Albanian Throne (pdf) – essay by Gëzim Alpion (2002), a British scholar of East European studies.

- Baron Franz Nopcsa In: Encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender & queer culture

- Histories: King of the duck-billed dinosaurs – magazine article by science writer Stephanie Pain (2005).

- Scientific American 2011. 09. 29. The Life and Legacy of the Dinosaur Baron

- The Treaty of Trianon took away the first dinosaur discovered in Hungary (an illustrated 2007 essay by Stöckert Gábor) (Hungarian)

- Discussion of his book by author István Fõzy (Hungarian)

- Information regarding the book by Fõzy (Hungarian)

- Article about Fõzy and his book on Nopcsa (Hungarian)